Acknowledgements

This research project and related results were made possible with the support of the NOMIS Foundation.

1. Understanding transitions

Initially, the study of transitions towards more sustainability in a food system (Kneen, 1993; Lebel & Lorek, 2010; Marion, 1986) was focused on production (Duru et al., 2015; Horlings & Marsden, 2011). Later publications attempted to understand the logic of sustainable agriculture by comparing different economic models: Hill (1998)distinguishes between 'weak' and 'deep' sustainability; Wilson (2008) contrasts 'weak versus strong multifunctionality'; Levidow et al. (2013) speak of an opposition between 'life sciences' and 'agroecological sciences' (2012). More generally, the literature contrasts 'natural' growth with 'industrialized' production (Plumecocq et al., 2018), i.e. between systems based on intensive means of agricultural production, also known as 'the incumbent system' and new initiatives, which possibly are the prefiguration of future systems that aim to preserve and restore 'natural capital' (Schumacher, 1991). However, such typologies have often been constructed in a monodisciplinary way, focusing on the technical and scientific dimensions while neglecting social values and practices.

More recently, when the limits to growth (Meadows et al., 1972, 2002; Turner, 2008) became obvious and especially with climate change becoming more salient, the awareness of the need to change the socio-economic system grew, giving rise to an explicitly transdisciplinary field to study systemic change (Patil, 2022). Starting from the ecology of complex systems and aiming specifically at understanding sustainable systems and the transition towards them, this set of the literature explores how to unfreeze socio-technical systems and enable transitions towards a sustainable and equitable economy within planetary boundaries operating under new socio-technical regimes (Fuenfschilling & Binz, 2018; Geels, 2002; Geels & Schot, 2007; Hess, 2014; Kemp, 1994; Kivimaa et al., 2019; Köhler et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2010; Stam et al., 2023; Truffer et al., 2015; Turnheim et al., 2015; Wieczorek, 2018).

Frequent approaches include 'strategic niche management' (Kemp et al., 1998) and 'transition management' (Loorbach & Rotmans, 2006). Most of them are based on the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) framework, which consists of three analytical levels: niche, regime, and landscape. According to the MLP, typically, innovations emerge and develop in a niche. They move up to the regime level where established socio-technical systems are located. The landscape comprises the broader socio-economic and cultural context. Drawing on transition theory and the Multi-Level Perspective, four distinct governance approaches have been identified: a hierarchist mode, individualist mode, fatalist mode, and egalitarian mode (Douglas & Wildavsky, 1983; Tukker & Butter, 2007). In practice, these theoretical concepts are interpreted differently from case to case.

Loosely related to this theoretical body of work, localised empirical studies continue to be carried out, usually based on long-term ethnographic work and involving interviews. Investigations into the transition in practice are as varied as they are eclectic: social and agricultural cooperatives (Cary, 2019; El Karmouni & Prévot-Carpentier, 2016), self-managed food shops (Jochnowitz, 2001), networks linking farmers and consumers (Blanc, 2012; Rudulier, 2010), organic farms, etc. Moreover, the geographic location varies widely, as does the political and economic context. This renders meaningful comparison impossible, and generalizations can only be drawn at a high level of abstraction.

A recurring finding, however, is the challenge posed by the dominance of incumbent systems and/or incumbent actors in achieving rapid and transformative change (Eakin et.al., 2017). Incumbent systems, institutions, and organizations are resilient and resist change (Pinstrup-Andersen & Watson, 2011); actors have vested interests to defend and are risk-averse and the transaction costs of change are substantial (Chase & Grubinger, 2014). Indeed, communities of knowledge and practice are also communities of interest, and they have set up, through a history of struggle and compromises, institutions and regulations precisely to maintain a status quo that is favourable to their interests. They use it to bar from entering those initiatives that jeopardize the current system. 'The co-evolution between artifacts and representations is done under continuous monitoring and control of stakeholder communities, which use institutions as social and economics tools to safeguard their interests. This is one more factor of stability of this normative framework' (Lahlou, 2008). As a result, innovative initiatives tend to occur in specific 'niches' where a window of opportunity exists, led by 'change agents' or 'champions' (Lahlou et al., 2011); or where innovation spreads where and when sufficient conditions are met. Whether they succeed in being taken up and spread depends on the resistance they encounter or on conditions that favour them and other factors. Despite these scientific efforts as shown in the substantial literature, the search for robust and operational models of the conditions and mechanisms of systemic transitions is still open.

2. The research gap: big data vs deep data, systemic vs local

The field of studying the transition of food towards greater sustainability is fraught with two pitfalls. Many studies propose typologies to identify the negative effects of the dominant system and focus on the obstacles to transition, while maintaining a distant relationship with what happens on the ground. The multiplication of typologies comes with an over-theorisation that is often far removed from the data in the field, at best relying on aggregate data. On the other hand, surveys based on local case studies attach great importance to detailed descriptions of the transition in progress, but how the findings can be generalized is difficult to assess. So, the possibilities to generalize come up against the contextualized specifics encountered in the field. The 'typology game' and the 'trap of the local' represent the two extremes in the field of transition studies.

This situation has some historical antecedents, involving different research communities, but it is exacerbated by a research gap: so far, it has been difficult to combine breadth and depth. It is very time-consuming and costly to do in-depth research. The analysis of one in-depth study is so labour-intensive that it is not imaginable for a single team to go beyond a few dozens of such cases 'manually'. Thus, the dilemma is one of 'big data' versus 'deep data'. In the first case, one can utilize large samples of mostly economic data, which are typically collected through ad-hoc surveys or bring together data that have been collected for other, often very different, administrative purposes. In the second case, one must rely on detailed, in-depth cases studies that are too specific, scarce and too-widely distributed to enable comparison and generalization. One would hope that by collating the many existing in-depth case studies this conundrum can be solved. Alas, different researchers and their teams use different data collection frameworks and putting all these data together proves to be very difficult, if not impossible.

3. The Food Socioscope project

The Food Socioscope addresses this twin research gap (big data vs deep data and systemic vs local) with several strategic moves. Firstly, by assembling and training a large team of local interviewers dedicated to in-depth data collection 'on the ground', using the same strict and well-tested protocol in different countries. This enables to go 'deep' locally, with a common understanding and methodological framework. This comes with a cost and strong organisation that is beyond the capacity of cottage industry. Secondly, by deploying the latest developments in AI modelling to process, code and analyse the data, therefore going 'big' by analysing together and systematically a vast number of 'cases'. This addresses the limitations of the workforce of a single human. It also facilitates replicability. The Socioscope thus aims to show that it is possible to scale up the collection of in-depth qualitative data by combining their processing and analysis with AI-assisted quantitative methods.

Thirdly, the Socioscope project was freed of some institutional limitations of the 'project-contract' system that has become the mainstream standard of funding. These institutional limitations, which straitjacket with 'deliverables' and 'deadlines' the research into what is expected before the project starts, are hardly compatible with frontier research that needs to break new ground. The Socioscope has the benefit of being funded by the Nomis Foundation with an unusual openness regarding the methods used and the 'deliverables' to be expected. The Foundation explicitly encouraged the exploration of finding the best ways for data collection and processing and the optimal responses to the challenges posed by this new kind of large-scale qualitative research (LSQR). The light-handedness on the pressure to publish enabled the PIs to conduct a substantive and careful proof of concept phase, in which they felt free to explore various solutions, and to fail several times, before finding the procedures and controls that were finally implemented. In fact, two full years were spent in exploring and testing that resulted in the creation of a solid proof of concept, including a fully operating netboard (see below). This paper is the first published document of the project. It is sad to say that such a situation where we have time to try and reflect before we publish has become extremely rare in academia.

In short, the project is based on the assumption that in-depth data as well as a systemic scale of sampling are both necessary to understand systemic transitions. Especially the mechanisms connecting the micro, meso and macro levels must be considered and become anchored in the data collection. This is difficult because the classic approach of in-depth investigation is to consider the initiatives that are studied as 'cases'. Inevitably, by doing so they are reified as an entity per se by the process of making them a 'case', while in fact they are only one component in the interlinked fabric of the larger system. They only exist and make sense in relation to the larger system. To take a (caricatural) metaphor, it is not because you cut a piece of an animal that this piece can be understood as a self-standing organ. While we were aware of this conundrum, we underestimated the difficulties. Interestingly, while, as seasoned scientists, we felt confident in our initial approach, as we progressed, we had to humbly realize that many things we took for granted require change or adaptation to operate in-depth but at systemic scale. LSQR opens new and different pathways for social science research, as we outline below.

So, as a research project the Socioscope uses a pioneering methodology to analyse 'what happens on the ground' in the transition processes towards greater sustainability in the domain of food production, distribution and consumption. We collect highly detailed qualitative data on hundreds of local initiatives around the world that seek to promote positive developments and/or reduce negative externalities, like new forms of organic farming, innovative food transformation and distribution forms that are based on minimizing ecological footprint, favouring circular economic models, etc. The data include videos and field interviews on these activities, and the collection of data on the transactions with the local and larger system (economic, social, environmental and administrative-political).

Machine learning tools allow us to process and analyse this vast amount of qualitative data to link the micro, to the meso and macro levels, and hopefully to identify risks and the factors that contribute to success and failure. After 18 months of developing and testing a prototype with 60 initiatives, continued funding from the Nomis Foundation permits us to scale to up to 600 initiatives on four continents in the coming two years. We are now confident that our methodology allows for rigorous comparison, and our cloud-based, open, infrastructure will lead to new ways of conducting collaborative science on complex systems.

Gathering in-depth data at large scale is not easy -- which is precisely the reason for the research gap discussed above. Beyond the mere cost of multiplying in-depth explorations, and the need to assemble, fund, and manage a large team over time, we seek to address another, often neglected, issue. In-depth data collection requires substantial collaboration by those very people who are the source of information, in our case the participants in the initiatives that are studied. Responding to field interviewers is demanding, as it takes time from busy people and the questions asked can be felt to be intrusive. Answering may involve discussing trade secrets and confidential economic and financial data, perhaps acknowledging failure. These are some of the known obstacles to collect information. Finally, 'survey fatigue' is hitting those initiatives that have become emblematic. Many scientists and journalists come to see 'good' cases and organizing visits and storytelling can become a time-consuming activity without much return. This leads to a question for the participants: 'what is in for them'? What do they get in return for participating? In short, how can we have a fair and balanced 'social contract' (Lahlou, 2024) with them?

Reflecting on these issues, and discussing with the participants during the proof-of-concept phase of the Food Socioscope in nine countries, led us to adapt our initial approach of collecting 'case studies' to feed the research. We realized the need for building a solid base for participation in order to ensure good data collection 'in time', but also to be able to follow up the evolution of initiatives 'over time'. This requires enrolling participants in a contract that motivates them to participate and keeping them motivated. Such a contract must offer benefits in return for providing data: making the work of participants visible and useful for others; becoming part of a community of other initiatives in which information is shared; learning valuable know-how from peers close or far, and gaining the capacity to get in touch with those peers they want to exchange with. This adds to the usual incentive of participation in case studies. Furthermore, participants get the feeling that they are respected by scientists as partners in a valuable and important initiative that offers them the opportunity to reflect on their practice with experts during the interview.

The 'Netboard' (the on-line platform where the cases are showcased, see section below) does not create or invent such functions: usually, the practitioners have already set up multiple local communities of knowledge and practice (CKP) that serve some of these functions. For example, the 'Scuola esperenziale itinerante di agricoltura biologica' is an attempt to learn and teach how to do organic agriculture, share resources, and create a local community which we encountered in three initiatives we studied in Italy (Conca d'Oro, Madre Terra, and Villa Angaram). The AMAP movement (Associations pour le maintien de l'agriculture paysanne), inspired by the American CSA model which in turn is inspired by the Japanese teikei model (Lagane, 2011; Mignot et al., 2022; Mundler, 2009; Olivier & Coquart, 2010) is another of the many examples we met along the first phase of our research. Almost all the initiatives we studied were involved in one or several larger groupings and organizations, as has been found in other research (Hinrichs, 2000). However, these organisations are loosely connected, and there are many silos. Nevertheless, their very presence demonstrates the need for tools of facilitation and capitalization of know-how, opportunities to create CKPs, and collective action. This explains our choice of supporting the existing communities and fostering the creation of a larger network, while leveraging the demand for such networks in our attempt to reward participants for their contribution.

All this makes the Food Socioscope an original endeavour, in some respects similar to action research. We believe this sets the direction for what will become a characteristic of future research on systemic change: a participatory endeavour, where scientists and practitioners collaborate in the long term, sharing the aim to change the system, as they gradually understand together how it works. As psychologist Kurt Lewin, the founder of action research, aptly noted: if you want to truly understand a system, try to change it.

However, and in contrast to classic action research, our goal as scientists is not to change the system through various kinds of 'interventions' or to claim that we know how to 'manage' transition. Rather, we think the role of scientists is to embed in the actual socio-economic system a 'reflexive installation' (the netboard) that supports research activity while also supporting the activity of the practitioner community. Therefore, the netboard installation has two functions. First, for the community itself: it empowers the community to visualize its own state and to communicate inwards and outwards, facilitating reflexivity and action, and therefore to promote directed change by organizing and monitoring. These are the affordances of the netboard as cartography, dashboard, showcase and directory which have been designed in order to support the Food Socioscope community of knowledge and practice (CKP).

The second function, by virtue of collecting, and making available for analysis the state of the system and its evolution, is to enable research at scale in space and time. These are the data repository and archive affordances of the Netboard and of the deep data storage and management system. Note that these data are collected but not made publicly visible in the netboard. These functions support the Food Socioscope research project.

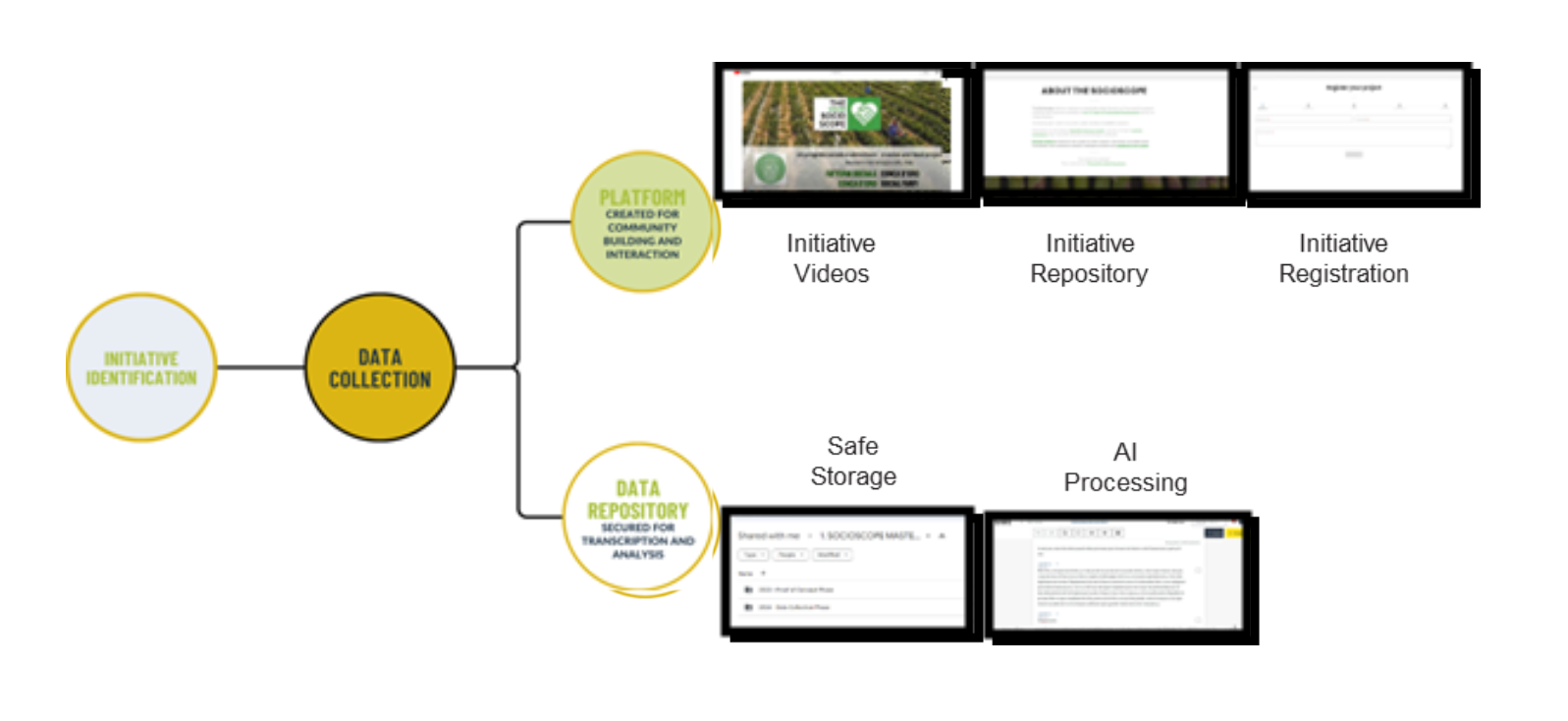

Figure 1 depicts the first part of the Socioscope which is dedicated to data collection and the support of what we hope to become a global CKP in sustainable food provision (including primary production, transformation, transport, storage, retail, preparation, consumption, waste management and all the supporting infrastructure and organizations). This data collection, carried out in collaboration with the participant 'initiative holders', is operated by a dedicated local team of trained interviewers and leverages a specific instrument, the Food Socioscope Netboard, a common web-based resource that combines the functions of a directory, a database and a showcase. Some of the collected data is public and feeds the CPK with basic information about each initiative, contact details, and in some cases short video clip presentations. Initiative holders provide information about their initiatives, which are described as 'cases' in the data set and are valorised by a specific page in the Socioscope Netboard. The Food Socioscope Netboard is openly available here: https://thesocioscope.org/

As said above, there is no intention on the part of the Food Socioscope team to 'direct' the CKP. Instead, we facilitate its self-management. But the Socioscope team is aware that such communities hardly take off unless they are scaffolded with minimal structures and support; and if these structures are deficient the CKP may decay. The Socioscope provides those support functions with its Netboard as a resource to that community. From the perspective of the research team, the Netboard is a service given to the community in exchange for the opportunity to collect the data necessary to understand systemic change. It remains to be seen whether and under which circumstances the Netboard will fulfil the potential it offers as a dynamization space for CKPs.

Part of the data collected during the visits of initiatives by the Socioscope interviewers is not public. It is accessible for the research team only, in order to analyse the mechanisms and conditions of systemic transition. By addressing the issues of confidential data and guaranteeing privacy by following RGPD regulations, participants are encouraged to contribute important economic, financial or technical elements that are essential for the research project but which they do not want to see published. This data is processed with sophisticated tools, including AI models, that enable analysing this massive corpus in a comparable way. Processing data with AI models brings with it new issues, e.g., we had to design a specific architecture and processes to protect the data against intrusion and leak, while still enabling their use. This architecture will be described in another paper.

The Socioscope Netboard is managed by the Paris Institute for Advanced Study, and benefits from its infrastructure, networks and connections with universities and specialized research institutions. The Socioscope project, led by Saadi Lahlou and Helga Nowotny, is a collaboration between the Institute for Advanced Study Paris and the Complexity Science Hub Vienna.

The sections below detail the Socioscope's two parts: the platform/Netboard (4) and the research project (5).

4. The Netboard: a CKP platform for data collection and community directory

The platform supporting the Food Socioscope online, the Food Socioscope netboard (openly available at https://thesocioscope.org/), shares data on initiatives, policies and research related to the food system transformation.

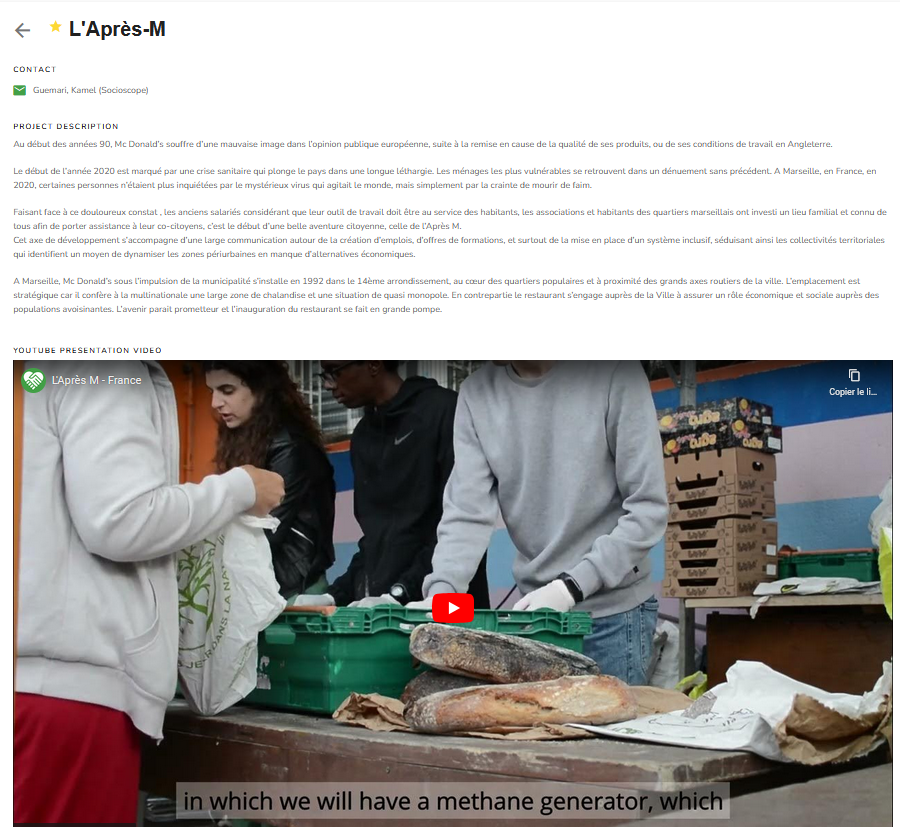

The Food Socioscope Netboard allows groups and organizations to promote initiatives addressing food system sustainability issues. They can easily enter their experiences, results, ideas, recommendations, offers and requests for collaboration. Each initiative can create its own page in a matter of minutes. This page serves as a shopwindow to publish, for the benefit of other members of the CKP, current or potential, what the initiative does. The page includes a 'contact' button, enabling those who want to get in touch to do so. The online interface is extremely simple, allowing data to be entered in just a few minutes (project name, email address, short summary, link to a website if applicable).

The Food Socioscope netboard, as seen by the user, is a global showcase of projects, a directory of actors in the sector, a library of cases, a compendium of solutions, a communication tool, and a platform for networking. Different measures to promote engagement with the platform and the creation of networks among initiatives will be tested as the project progresses, using the learnings we acquired creating and maintaining similar netboards and the design and implementation of a public engagement strategy.

As we argue in the seminal paper on netboards (Lahlou et al., 2024), promoting and maintaining a CKP is difficult but can lead to considerable benefits for the collective. By providing a clear, open, and easy to use directory of who is doing what and who knows about what, as well as how to contact them and how to join the network to make my own initiative visible, it can become a fundamental resource to find the right information and the right partners in times of informational overload (even across industries, sectors, and continents). Furthermore, an alert system enables users to get automatic emails with links to newly entered initiatives that are relevant to their own work.

5. The research project: building an instrument for Large Scale Qualitative Research to understand transitions.

Large Scale Qualitative Research is a frontier field. While we initially thought that this would be simply adding a text mining phase to qualitative studies, which we were familiar with, it turns out to be a different game. The process of scaling-up involves a considerable industrialization of qualitative data collection, structured data management and control, and finally a methodological strategy of continuous technical update, as the AI models we use in our processing chains are changing continuously. Ten months after starting data processing with AI, we are already in our tenth prototype of the chain, having used nine different AI models (not counting their versions). We realize that, in contrast with what we used to do, it is the data that are the stable part of the research, while the techniques are changing.

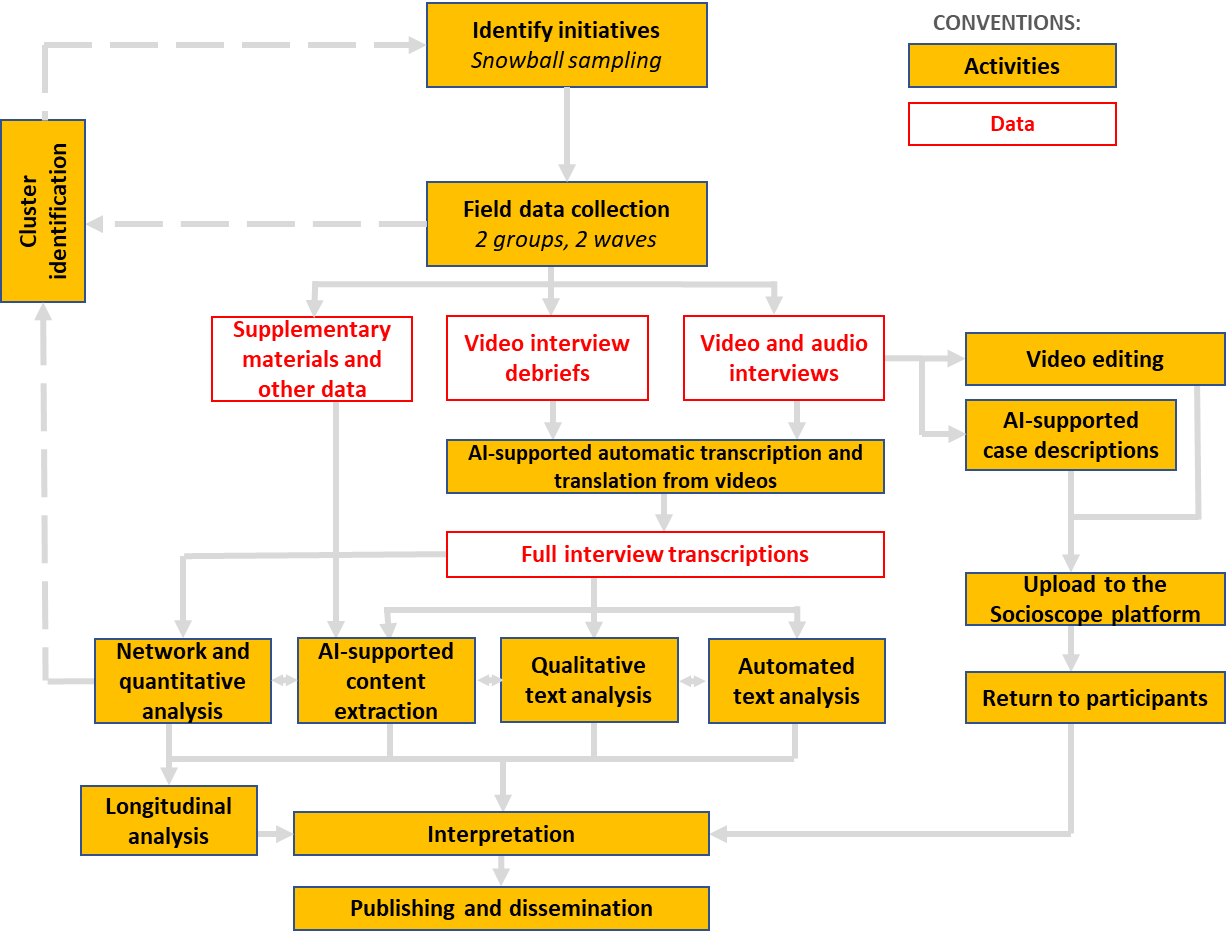

LSQR involves a more structured and documented approach of the research process, with very explicit procedures, division of labour, and quality control, in contrast with the often idiosyncratic and 'cottage industry' approach of classic qualitative research. Practically, we had to set up a new organizational format, with detailed tasks and job descriptions as well as carefully thought-through processes for following work in progress. The research team includes a full-time data collection manager (with legal training and vast experience of large-scale project management) and several quality control officers. The team produces a detailed protocol for the data collection, with strict guidelines, in addition to their presentation in four tutorial videos. Local interviewers are trained by qualified personnel, and benefit from a permanent support desk with a hotline. We find and appoint coordinators who are locals, based in specific geographic regions (e.g. Latin America, Western Europe). The editing and management of the video clips is a separate strand of the overall organization, with editors competent in the language of the interviews. The progress of data collection, quality control, processing and storage is followed for each case with a detailed dashboard that monitors, supports and controls every step of the procedure for compliance with the protocol and data quality. This ranges from the selection and validation of initiatives to contact initiation, actual visits, and the uploads, transcription, debrief, etc. of the data collected. Therefore, the central data collection management team has a detailed, continuously updated vision of progress of the field work in the main dashboard.

We have added another feature in the process of collecting data which, to the best of our knowledge, is original and innovative. After returning from the field and having uploaded their films, the recordings of the interviews and complementary materials, each interviewer engages in a recorded debrief interview, usually lasting about 1:30 hours, with the central data collection team in order to check all points of data collection, clarify acronyms and names used, and more generally, extract from the interviewer additional details and reflections on the initiative surveyed that may not appear, or not clearly enough, in the uploaded material. This is an attempt to make explicit the tacit knowledge about the case the interviewer has gained in the field about the initiative, as we are aware that audiovisual recording, even though it helps the analysts to get a better understanding of the initiative, still implies a loss from what the interviewer experienced in the field. This debrief interview is conducted via videoconference, recorded and transcribed to become part of the empirical material of each 'case'.

But there is another aspect that is original in the data collected by the Socioscope. As we are interested in understanding the relationships between the micro, meso and macro levels, the data collected are systemic in nature: we take care, during data collection, to systematically collect data regarding the relations of each initiative with its larger environment. While this is naturally part of every good case study, here we use a systematic grid based on the notion of social contracts (Lahlou, 2024), which describe the functional and behavioural agreements that agents have in their set of transactions with other agents in their ecosystem. For example, the relations between a provider and a client go beyond the mere transaction 'product for payment'; there are also long-term agreements on price, quality, exchanges of administrative and accounting information, delivery etc. For long-term relationships, such as the ones between a company and its municipality, that often involve third parties in transactions, it is even more complex. The notion of social contract accounts for the fact that transactions are not independent: structural relations between agents involve a nexus of the kind 'if you give this, you get that'. Usually, 'this' and 'that' are sets that are exchanged over a many, and not a single transaction with reciprocal expectations in time. Therefore, it is necessary to have a systemic view of the contracts to understand the relations within an ecosystem. This is achieved with the stakeholder transaction grid (see below).

As a result, the empirical material for each case consists of a detailed description of the initiative by the initiative holder, comments by the interviewer, video recordings that illustrate the various activities of the initiative, and supplementary material (e.g., the systematic 'scraping' of the initiative's website and all documents provided by the initiative holder during or after the visit). All this rich material is transcribed and translated before being securely stored with our AI -augmented processing chain, ready to be processed for analysis.

Figure 3 shows the current data collection and processing chain:

6. A preview of preliminary results

So far, we are only in the first year of the Food Socioscope project in its production version. It took a few months to set up the data collection machinery and bring the first one hundred thirty cases to conclusion.

Even though we have not yet started the full analysis as we are still in the data collection stage, we could not help but have a quick analytic peek at the data. Several interesting findings already appear, which shed a different light on the relations of the initiatives with their ecosystem, as our sampling strategy includes some snowballing: when we study a case, we also go to study other initiatives that are stakeholders for this case, e.g. providers, the municipality, etc. We briefly give some insights below; of course these are only preliminary appetizers.

Regulation and local government

While the literature tends to focus on the initiative of economic agents themselves, the role of regulation and of the local powers appears paramount in our data. In almost every case we surveyed, the municipality or the region contributed, usually financially, to the emergence and initial survival of the initiatives. This is understandable since, as the initiatives are transformative, they do not fit well in the incumbent regulatory and market frameworks and need some push or at least extended benevolence to exist, as well as some financial input to survive until it finds its place in the ecosystem. Privileged relationships with a 'confederate' in the local incumbent system appears as a facilitating factor for success, in line with what has already been observed in the energy and housing sector (Lahlou et al., 2011).

This relationship is often political on the governance side (e.g. meeting electoral promises, following the party's priorities), while it tends to be more pragmatic and instrumental on the side of initiatives. Adjustments are often opportunistic and local, and many could serve as illustrations of the garbage can model (Cohen et al., 1972)where carriers of solutions randomly meet carriers of problems. The specificity here is that initiatives are often solution carriers who actively look for carriers of problems who can fund or otherwise foster their solution. On the other hand, carriers of problems are the ones who have the budgets (municipalities, agencies, public society...). They tend to select incoming initiatives, or make calls for solutions, rather than actively create such solutions themselves.

The asymmetry of social contracts

The investigation of social contracts consists in listing all the entities the initiative is in a transaction with (clients, providers, partners, competitors, local powers etc.) For each contact, we ask the participants to describe the transactions they have with them as seen from their perspective, but also, as they understand it, from the perspective of the other. But why not simply ask participants what they give and what they receive? Why ask twice the same question from the perspective of the initiative, and from the perspective of their partner in the transaction? The answer comes from the results of our pilot study.

When investigating the social contracts (Lahlou, 2024) that the initiatives have with their ecosystem, we were surprised to discover that this game of exchange as we capture it with a grid, is in fact dual. Participants seem to play the same game, but in fact that is not exactly the case. Indeed, what the initiative participants believe, as seen from their perspective, they give to a specific stakeholder and what they get from that stakeholder, is not necessarily what conversely that stakeholder believes to give or to receive in the transaction. To put it simply: in a transaction between two parties, the transaction as seen by one party can be different from the 'same' transaction as seen by the other party.

Take the example of an initiative whose initial aim was to create sustainable jobs for talented women, often coming from difficult backgrounds, particularly as cooks, using their basic culinary skills. We show in Figure 4 Figure 1 the specific lines in the transaction table describing the transactions this initiative has with their social landlord to whom they pay rent. While the transaction includes the classic economic aspects (rent vs space), it appears that there are other 'currencies' that are exchanged, which matter to the participants regarding their purpose.

The social landlord is interested not just in getting the rent, but in improving the image and reputation of the neighbourhood, by having 'good' organizations settle in this deprived neighbourhood. Also, the social landlord is aware that by providing a location to the initiative in such a neighbourhood, it contributes to the initiative's social impact, which it knows is part of the initiative's purpose. In fact, the social landlord precisely selects the initiatives which it works with, on the basis of purpose and not profit. Obviously, the social contract (and transactions involved) between the initiative and the social landlord would not have occurred if these aspects were not present. Note, and we'll come back to this, that these are not the aspects usually taken into consideration by mainstream economics when studying the real estate market. These items are automatically extracted by our AI models from the verbal material, and the last column provides some verbatim that justifies the content of the cells in Figure 4.

| stakeholder | What initiative gives | What initiative gets | What partner gives | What partner gets | Verbatims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social landlord | Rent, | Local and Space | Social Impact and Community Development | Income. Improved Neighbourhood Image and Reputation | - 'We were able to secure premises with a social landlord, in a neighbourhood that wasn't the one we'd chosen, but the one that was allocated to us.' - 'We were creating jobs in working-class neighbourhoods, for people who live in working-class neighbourhoods.' |

A transaction may include simultaneously several objects, currencies and values. Some of these are considered as relevant for one party, but these are not necessary the same relevant ones for the other party. To take another simple example, in the transactions following the 'media model'. In this business model the reader of the newspaper perceives the transaction as giving money to get news, while the media owner sees the transaction with the reader as providing stories to a public in exchange for money and attention. The latter (attention exchanged in the transaction) is not perceived by the reader as part of the transaction. Nevertheless, it is a very important part of the transaction for the media owner, because it becomes a resource the media owner sells on the as 'audience' to advertisers. That is why the media business model is a double-sided market (Rochet & Tirole, 2006; Rysman, 2009), where what is gained on one side of the market (attention gained from the reader), is exchanged for something else (here, money)

with the advertisers on the other side of the market. When we look closer at our initiatives' economic models, it turns out that most of them are actually operating on multi-sided markets, where they gain something from a given stakeholder, and re-use that something gained from another stakeholder, from whom they get something they exchange with the first stakeholder, or it another one.

This multi-dependency is characteristic of complex systems, it is an important aspect to consider in systemic transition processes. Whenever a part of the system is touched or activated, it has reverberating impacts through the social contracts involved.

In hindsight, this asymmetry of the exchanges (what matters most for one party is not necessarily what matters most for the other) is easily understandable, since the motives of the activity of the parties differ. Nevertheless, that asymmetry opens an interesting series of questions for research, also regarding the data collection and analysis techniques that will enable to take these aspects into account.

These issues matter to explain the insertion of an actor playing in a different (target) model while managing to survive in the incumbent ecosystem. For instance, the consumer is happy to buy the organic tomato because it tastes good and the price is acceptable, and the farmer is happy to sell it because it is organically produced according to her ethics and the price enables her to operate. In this transaction, the consumer plays following the game of the incumbent market system (give cash get product); while the farmer plays both games, following the rules of the incumbent system (sell products for cash) but also the rules of the sustainable target system (make a living through producing organic). The same exchange can be considered valid in both systems,(incumbent and target). E.g. the consumer is happy to buy the organic tomato because it tastes good and the price is acceptable, and the farmer is happy to sell it because it is organically produced according to her ethics -and the price enables her to operate.

We believe this finding of the 'relativity of transactions' depending upon the reference frames of the parties involved, has major implications for economic theory and needs to be investigated further to understand the conditions of transition from one system to another, and the coexistence of different systems. It suggests that contrary to the idea that in a transition new types of initiatives (and their economic model) would substitute the incumbent ones by driving them out of the market through better fitness and competition, the mechanisms might operate through an overlap of business models and a combination of transformation of the incumbent actors and gradual exclusion of the less fit.

Motivation beyond economic rationality

Interestingly, the usual economic incentives found within the classic forms of economic models, e.g., profit, competition, growth, are partly or totally absent from the motives declared by our participants. Especially, not only 'growth' is rarely mentioned, but when it is, than it is mostly to be rejected as a motive.

To put it briefly, this first peek at the data suggests that the transitioning initiatives we surveyed do not operate under the principles that we have learned to be the classic basic economic principles. Again, this is akin to what has been observed in the energy and housing sector for local sustainable experiments where, as (Lahlou et al., 2011: 187) put it 'the economic actors' behaviour cannot be explained by economic rationality alone. Just as in the case of the economics of culture and the arts described by (Lahlou et al., 1991), the economic actors are in fact driven by passionate motives that make them act beyond economic rationality. Here this rationale may be a green ideology - hence the importance of individuals at this stage'.

In contrast with an approach that would consider the economic agent motivated only by self-interest, we encountered initiative holders for whom their impact on others was important, and who were moved by empathy, closer to the individual described by Adam Smith in his theory of moral sentiments (Smith, 1759) than to the rational and maximizing economic agent of which Gary Becker's work (Becker, 1981) provides an extreme example. Bourdieu noted that '... the constitution of a science of mercantile relationships ... has prevented the constitution of a general science of the economy of practices, which would treat mercantile exchange as a particular case of exchange in all its forms.' (Bourdieu, 1986). What we see in our investigations is precisely that, for our participants, the non-mercantile aspects of exchange are at the very core of their motives and of their behaviour. That is understandable since, precisely, they try to transit to another model than the incumbent one, where economic exchanges are focused on the mercantile aspect.

All this makes us think that economics as we know is not so much a generic science of exchanges but rather the discipline that models a specific type of economic system as it exists today, one that has been dominant in Western countries in the last two centuries. If we want to understand systemic transition, perhaps we should come back to the roots of political economy, and take an approach grounded in the empirical analysis of what actors actually consider as the meaningful and important transactions, an approach that takes into consideration a larger set of motives, values, currencies, transactions and social contracts and would be sufficiently generic to study the current liberal capitalist system, but also those economic systems that preceded it, and those that are emerging to replace or amend it and, hopefully, will lead to more sustainable futures. But this is an empirical issue, and our analysis is only beginning.

7. Conclusion

The Food Socioscope project is an innovative step forward in understanding and promoting the transition towards sustainability in the food domain. By building a new instrument that enables the scaling-up of qualitative research, the novel combination of rigorous data collection across continents, AI-powered data processing and analysis, and the promotion of a global community of knowledge and practice (CKP), we attempt to bridge the gap between 'big data' vs. 'deep data' and 'systemic vs. local', thereby opening up new perspectives for the social science, understanding systemic transitions, and sustainability research.

The Socioscope allows us to create, test, and document significant innovations in the ways the social sciences approach the study of social challenges and systemic transitions in at least three areas:

-

First, in the design of a sophisticated organisation for research (including organisational processes and procedures, assembling and training a large team, setting up data infrastructures) for the collection of hundreds of in-depth local case studies for a specific domain. In the domain of food, this includes 600 initiatives that are promoting greater sustainability across continents, industries, and sectors. The data is collected in a way that allows for reuse and follow-up.

-

Second, in the possibility of scaling-up qualitative research by processing and analysing unprecedented amounts of qualitative data using AI/LM tools, potentially opening the gate for the wider use of large-scale qualitative research (LSQR) approaches to lead the way in the study of complex societal challenges.

-

Third, in the creation of an online platform, the Netboard, that has shown the potential for creating a dynamic and participatory community of knowledge and practice around the themes of the research project. The creation and promotion of such networks of collective intelligence can greatly inform efforts to tackle the complex societal challenges.

The progress achieved in the natural sciences is largely due to the invention and use of new instruments and techniques, which allows new kinds of observations and the collection of data. Just as the microscope enabled biology to delve deeper and the telescope was essential for astronomy, we are confident that the Socioscope will bring new insights in the understanding of socio-economic phenomena, and especially how processes of transitions occur. This will be based on the active collaboration of participants who have first-hand knowledge, know-how, motivation and goals. All innovation begins locally. By scaling-up the analysis of local initiatives, we expect to gain access to new and hardly explored areas of social science knowledge.