Recent debt crises have seen the rise or resurgence of various legal counter-cultures. This article examines one of their most structured expressions: the doctrine of odious debt. Situated within a broader set of efforts aimed at limiting the unchecked assertion of creditors’ rights, the doctrine contributes to an ongoing redefinition of the normative architecture governing sovereign credit relations. Although diverse in design and scope, these approaches share a core idea: debtors have rights and creditors cannot be absolved from responsibilities. In a marked departure from the orthodox conception of sovereign lending, they reject the premise that the mere extension of credit establishes an absolute right to repayment. On the contrary, creditors, too, may be held to standards of accountability, particularly when debt contracts are compromised by elements of illegitimacy.

The odious debt doctrine rests on a fundamental contestation of the legal validity of debts contracted under tainted conditions, especially when the borrowing regime lacks legitimacy or when the funds are used for purposes contrary to the public interest. Originally articulated in the early 20th century in relation to issues of state succession, the doctrine has undergone successive evolutions in both its criteria and scope, progressively extending to encompass cases of opaque and predatory lending. This adaptability underscores its doctrinal plasticity.

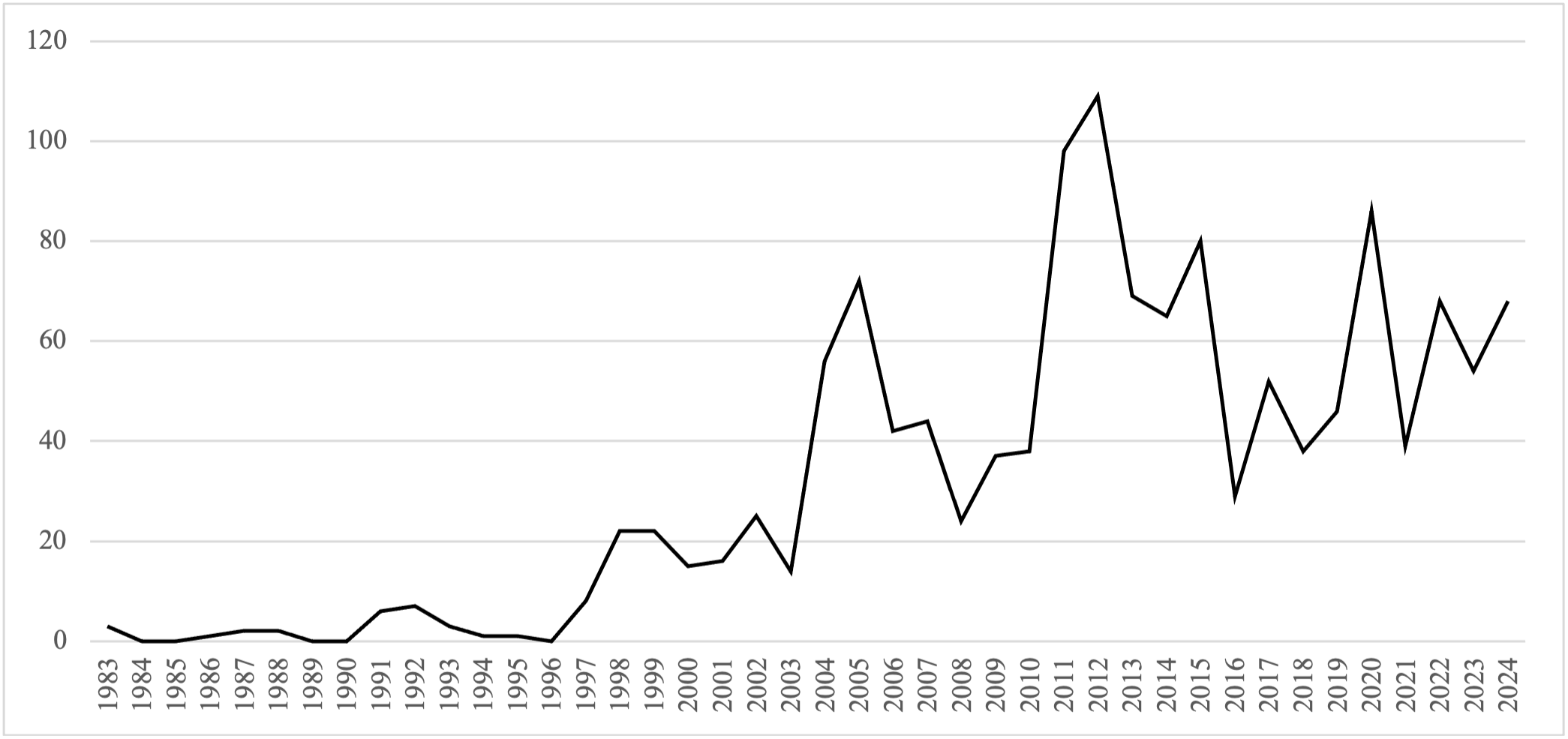

For over a century, the doctrine has fueled sustained and often contentious debate among legal scholars, diplomats, and economists regarding the legal foundations upon which debts may be deemed void due to their illegitimate character. From Cuba (1898) to Iraq (2003) and Venezuela (2017), and from Costa Rica (1923) to Ecuador (2006) and Greece (2010), it has been invoked in a range of disputes centered on the respective responsibilities of borrowers and lenders within the sovereign debt regime. The early 2000s marked a notable revival of the doctrine, spurred by the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative and further reinforced by key episodes such as Argentina’s 2001 default, the restructuring of Iraq’s debt in 2003, and the Ecuadorian debt audit of 2006. Since the outbreak of the European sovereign debt crisis in the 2010s, interest in the doctrine has persisted, with renewed attention in recent years focused on the Venezuelan and Ukrainian cases.

Figure 1: Occurrences of the term “Odious debt(s)” in global news sources, 1983–2024

Source: Factiva

The doctrine of odious debt challenges conventional legal approaches anchored in pacta sunt servanda, the principle that contracts must be held regardless of the conditions under which they were concluded. In opposition to this formalist view, the doctrine posits that a debt may be declared invalid if it was contracted under illegitimate or compromised conditions. From this standpoint, the justification for debt repudiation lies not only in cases of insolvency but may also originate in the structure and context of the contract itself. In doing so, the doctrine reveals contradictions within the legal order, insofar as certain contractual obligations may be unenforceable when weighed against superior legal norms or ethical principles. Yet the doctrine remains weakened by the instability of its criteria. This definitional uncertainty has significantly constrained its implementation: to date, no national or international court has formally invoked the doctrine of odious as grounds for invalidating a sovereign obligation (Buchheit et al., 2007). Still, this absence of legal recognition has not precluded its invocation in political discourse, public debt audits, or multilateral negotiations.

This paradox warrants particular attention: while the doctrine of odious debt claims legal authority, it functions primarily outside formal judicial settings, operating as a politico-legal narrative that enables diverse actors to converge around a shared framework for distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate debt. In this role, the doctrine serves as a tool of “sovereign debt diplomacy” (Pénet & Flores Zendejas, 2021, p. 6), facilitating the coordination of debt disputes in ways that are collectively recognized and deemed legitimate within institutional norms of international conduct. Within this diplomatic register, vagueness is not necessarily a weakness. Contrary to the prevailing assumption in legal theory that a principle must be clearly defined to be effective, the strength of the odious debt doctrine lies in its flexibility. Its influence comes from its capacity to unite different claims, circulate across political, activist, and financial arenas, and adapt to varied strategic and institutional contexts.

This article explores the evolving trajectories of odious debt from its initial formulation in the early 20th century to its current transformations. In the absence of formal recognition by national or international courts, the doctrine is progressively shifting toward a market norm, with the potential to be incorporated into financial institutions’ risk assessment and due diligence frameworks. This relocation of the debate from courtrooms to trading desks opens an unprecedented space for normative experimentation, but also calls for increased vigilance regarding the risks of strategic appropriation or normative dilution. In this context, odious debt in the 21st century appears as a doctrine in transition, situated at the crossroads of international law, financial statecraft, and the moral politics that underpin global finance.

Two doctrinal models: the Cuban and Costa Rican formulas

Contemporary debates on odious debt trace their origins to Alexander Sack’s 1927 treatise, Les effets des transformations des États sur leurs dettes publiques et autres obligations financières (The Effects of State Transformations on Their Public Debts and Other Financial Obligations). A Russian-born jurist based in Paris, Sack aimed to address the intricate legal challenges raised by state succession in the context of the collapse of European empires. When political entities break apart, as in the case of Austria-Hungary, or vanish altogether, as with Tsarist Russia, who bears responsibility for debts previously contracted? Sack defended a classical view: public debts, as binding contractual commitments, should be honored by the successor state exercising control over the affected territory. For Sack, the continuity of financial obligations constituted a cornerstone of the international legal order.

What sets Sack apart, however, is his introduction of an exception to the principle of debt continuity: certain debts may be classified as “odious,” and thus eligible for repudiation, based on their origin and purpose. He proposed three criteria (Sack, 1927, p. 146-147): debts are deemed odious and should not be repaid when they were contracted by despotic governments (criterion 1: lack of consent), for purposes contrary to the interests of the population (criterion 2: absence of benefit), and when creditors were aware of the first two conditions at the time the loan was issued (criterion 3: creditor complicity). These criteria, which define both the scope of the doctrine and the conditions under which it may be invoked, have generated extensive academic and activist debate (Nehru & Thomas, 2008).

A recurring controversy centers on whether the criteria must be applied cumulatively: must all three be satisfied for a debt to qualify as odious, or are the latter two sufficient on their own? Advocates on both sides claim greater fidelity to Sack’s original thinking. Yet the 1927 treatise is phrased in terms that are broad and ambiguous enough to make any literalist reading problematic. Scholars have referred to it as a “definitional swamp,” pointing to the conceptual vagueness of Sack’s articulation (Buchheit et al., 2007). This indeterminacy is not merely a matter of imprecise drafting; it reflects a constitutive tension within Sack’s project, caught between two contradictory ambitions. On the one hand, the effort to legally codify the wide range of historical justifications for repudiation (such as war debts, hostile debts, and regime debts). On the other hand, the attempt to restrict the doctrine’s scope in order to grant it distinct legal legitimacy within international law. It is within this tension that the doctrine of odious debt derives both its lasting malleability and its enduring interpretive fragility.

The Cuban precedent, which Sack identifies as an emblematic case, originates in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War of 1898. After its defeat, Spain insisted that the newly formed Cuban Republic assume responsibility for the debts previously contracted by the Spanish Crown, debts that had been backed by revenues generated on the island. The United States refused, invoking three main arguments: the debts had been incurred to finance the repression of independence movements, they had been contracted without the consent of the Cuban population, and the creditors were fully aware of these conditions. This reasoning—referred to here as the Cuban formula of odious debt—rests on the despotic character of the borrowing regime (criterion 1) and has proven particularly well adapted to situations of state succession. It has since been cited in a variety of cases, including those of Algeria, Iraq, and Ukraine.1

By contrast, the Costa Rican precedent, derived from the Tinoco case (1923), rests primarily on the criteria concerning the use of funds (criterion 2) and complicity of creditors (criterion 3), with the despotic nature of the regime playing no decisive role. In 1917, General Tinoco and his brother seized power in Costa Rica through a coup d’état, establishing a dictatorial regime. Following the regime’s collapse in 1920, the newly elected democratic Congress moved to repudiate the contracts concluded under Tinoco, most notably, an oil concession awarded to a British firm and a loan from the Royal Bank of Canada. This act of repudiation was soon met with the arrival of a British warship carrying a government minister. The dispute was brought in 1923 before an international arbitration tribunal chaired by William Howard Taft, then Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

While Taft affirmed the general principle of debt succession between governments, he ruled in favor of Costa Rica on the basis that the transactions in question were fraudulent, and that the bank either knew or ought to have known that the funds were intended solely for Tinoco’s personal use. In his decision, Taft stated that “the bank knew that this money was to be used by the outgoing president, F. Tinoco, for his personal support after he had taken refuge in a foreign country” (Buchheit et al., 2007, p. 1217). Taft did not call into question the legitimacy of Tinoco regime per se; rather, his judgment rested on the creditor’s complicity and the fraudulent nature of the loan. This reasoning—which may be described as the Costa Rican formula of odious debt—shifts the focus from the odious regime to the odious lender. It thus opens the way for a broader application of the doctrine, one that may be relevant even in democratic contexts.

For a long time, the dominant interpretation favored the Cuban formula, considering that all three criteria must be met for a debt to be deemed odious (King, 2016). More recent interpretations, however, suggest that Sack did not regard the despotic nature of the borrowing regime as necessarily decisive, and that the improper use of funds, together with the creditors’ awareness of such misuse, formed the doctrinal core (Ludington et al., 2010; Toussaint, 2017). This debate over the criteria is not merely a quarrel among commentators; it raises a broader normative question about the doctrine’s contemporary relevance and conditions under which it can be invoked. The rigidity of the Cuban formula significantly limits its applicability to the point of potentially rendering the doctrine obsolete in a global context where despotic regimes account for only a tiny fraction of global sovereign debt. By contrast, the Costa Rican formula enables the doctrine to move beyond its post-imperial foundations and adjust to the realities of contemporary debt relations. It prompts a fundamental question: can a legal principle originally conceived in the context of empire and colonial succession be applied within democratic regimes? In other words, can a debt be classified as odious in the absence of war or colonial domination? The Costa Rican precedent opens the door to such an extension. It allows for the activation of the doctrine in democratic contexts, insofar as the borrowed funds were misappropriated and the creditors were aware of this misuse. As we shall see, the Greek case offers a particularly compelling illustration.

However, both versions of the doctrine carry their own sets of limitations. The designation of a regime as “despotic” is inherently political and open to interpretation. Demonstrating either the absence of benefit to the population or the creditor’s complicity also presents significant evidentiary challenges, particularly in a context marked by the plurality of lenders and the fungibility of funds, which renders the precise tracking of resource allocation highly complex. Can certain debts be deemed “partially” odious? Do systemic corruption and poor governance suffice to justify repudiation? Furthermore, the doctrine still lacks formal legal recognition: no court, national or international, has ever adjudicated a case explicitly on the grounds of odious debt, prompting some to question its legal validity altogether. Yet such skepticism overlooks the doctrine’s extrajudicial vitality. It continues to be mobilized in political negotiations, public rhetoric, audit proceedings, and broader interpretive struggles. It is in this sense that the doctrine should be understood in the 21st century: as a living and adaptable normative tool, functioning outside of courtrooms and shaped by the political and legal purposes it is made to serve.

When odious debt serves the empire: the Iraqi case

The Iraqi case represents a critical juncture in the contemporary revival of the doctrine of odious debt, particularly in its Cuban formulation. In 2003, the restructuring of Iraq’s external debt, then estimated at $115 billion (including $38.9 billion owed to the Paris Club, $55 billion to other bilateral creditors, and $18.4 billion to private creditors), was undertaken under the leadership of the U.S. From the beginning of the occupation, the U.S. imposed a unilateral moratorium on Iraq’s debt and issued an executive order to protect the country’s foreign assets from seizure (Gelpern, 2005, p. 395). This move was intended to put pressure on Iraq’s main creditors, notably France (owed $8 billion) and Russia ($12 billion), to accept substantial debt cancellation. In October 2004, an agreement was reached with the Paris Club to cancel 80 percent of Iraq’s public debt. This arrangement was subsequently extended to other creditors in April 2006.

Contrary to retrospective interpretations, this process was far from consensual. Iraq’s debt was not simply erased “with the stroke of a pen”2 but followed an intense political and diplomatic campaign in which the doctrine of odious debt played a central role. As with the military intervention, two opposing camps emerged. On one side, the U.S. and the United Kingdom advocated for a 95 percent cancellation, arguing that it was justified by the odious nature of Saddam Hussein’s regime (Siegle, 2004). This position was promoted by several leading figures in the Bush administration, including Treasury Secretary John Snow, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, and Richard Perle, Chairman of the Defense Policy Board, all of whom called for the full cancellation of debts accumulated by what they described as the “vicious dictatorship” of the Baathist regime (Harding, 2003). On the other side, France, Germany, and Russia, the main bilateral creditors, proposed a more modest cancellation of 50 percent. France, in particular, argued that Iraq, with the world’s second-largest oil reserves, should not receive a more favorable treatment than the world’s poorest countries. At the G8 summit in Sea Island in June 2004, President Jacques Chirac stated that it would not be “appropriate” for Iraq to benefit from the same level of debt relief that had been granted to the 37 poorest countries in the previous decade.3

This divide reflected two competing framings: the U.S. invoked the doctrine of odious debt to justify an exceptional treatment, while France defended a conventional legal framework grounded on the rules of the Paris Club, which oppose any form of preferential treatment for a country so abundantly endowed with natural resources. The U.S. position ultimately prevailed, largely because of its invocation of the odious debt doctrine, which played a structuring role despite lacking formal legal status. It enabled the U.S. to frame the Iraqi case as a normative exception, apply diplomatic pressure on reluctant creditors, and legitimize debt cancellation beyond the conventional parameters of Paris Club procedures. This invocation also helped to neutralize potential legal challenges from private creditors or states such as Kuwait, which were seeking reparations that could have obstructed U.S. objectives, especially the privatization of Iraq’s oil companies (Stiglitz, 2003). The U.S. eventually scaled back its demands to an 80 percent cancellation of Iraq’s debt, a position that received the backing of the IMF, which departed from its usual emphasis on structural adjustment. The final agreement brought Iraq’s debt to the Paris Club from $38.9 billion to $7.8 billion. For France, this translated into an estimated loss of between 3 and 6 billion euros to its public finances (Merckaert, 2006, p. 88).

The legitimacy of the debts contracted under Saddam Hussein was never subjected to thorough scrutiny. The entire stock of claims was implicitly presumed odious, based chiefly on the illegitimacy of the regime (criterion 1). Yet a closer look at French claims suggests that the absence of public benefit (criterion 2) and creditor complicity (criterion 3) could also have been meaningfully applied. In the 1980s, Iraq allocated $15 billion annually to arms purchases, primarily from France and the USSR (Tripp, 2007, pp. 229-230). France played a central role in the accumulation of this military debt. Both Jacques Chirac and François Mitterrand actively supported the Baathist regime, and French diplomacy was heavily influenced by the interests of the arms industry. French companies such as Dassault, Matra, and Thalès flourished in this environment marked by secret commissions and widespread corruption (Lazghab, 2004). While military debt is not inherently odious, what made it odious in this case was the context in which the contracts were awarded. The lucrative commissions associated with arms sales enriched both French political parties and the Baathist regime (Merckaert, 2006, p. 87). It was not the military nature of the debt per se that was problematic, but the conditions under which it was contracted. In Iraq’s case, one might speak of a debt “mal acquise” (ill-gotten debt), due to irregularities in the awarding of contracts and the fact that a significant share of the funds was used for the personal enrichment of Saddam Hussein. Creditors, aware of these practices, could not credibly claim ignorance of the lack of public benefit.

For legal scholars, this episode highlights the ambiguity at the core of the doctrine. The U.S. administration invoked the concept of odious debt without setting up any independent body or audit mechanism to rigorously assess its applicability. This discretionary use, far from invalidating the legal character of the concept, illustrates that, in the domain of sovereign debt, law often serves an expressive function, and its effectiveness lies in its ability to consolidate political power. Although the doctrine lacks formal legal recognition, it nonetheless operates as law by generating normative authority through a legitimizing legal discourse that grants universal standing to what are, in essence, discretionary interests. This realpolitik approach to debt cancellation highlights the deep entanglement between legal instruments and state power. On the one hand, even the most unilateral forms of action require normative justification to be effective; on the other, the legal function of the doctrine never operates independently but is always shaped by the influence of sovereign authority.

Predictably, this use of the doctrine drew sharp criticism from many legal scholars and activists. The CADTM (Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt) denounced what it regarded as a selective and politically expedient application motivated by geopolitical interests, pointing out that other countries emerging from authoritarian rule had not received similar leniency (Toussaint, 2003). The U.S. invocation of odious debt also created unease among several long-standing proponents of the doctrine. Patricia Adams, for instance, called for the direct involvement of Iraqi authorities in conducting an audit to formally assess the odious character of the debt (Adams, 2004, pp. 12-14). However, this proposal encountered resistance from the Iraqi leadership, which adopted a cautious approach. While some religious leaders and civil society figures publicly supported cancellation on the basis of the former regime’s illegitimacy, the main negotiators chose not to invoke the odious debt doctrine. Their strategy aimed to avoid a direct confrontation with financial markets and to steer clear of the reputational stigma associated with repudiation (Buchheit et al., 2007, pp. 20-21). Adil Abdul Mahdi, then Finance Minister of the Iraqi interim government, instead advocated for debt relief on the basis of insolvency, aligning the official discourse with the normative standards favored by international financial institutions (Salmon, 2004). This strategic silence reflects a broader reluctance among many states to invoke the doctrine explicitly. South Africa, for example, adopted a similar position regarding its apartheid-era debt, motivated by concerns over potential stigmatization or marginalization within the global economic system.

This interplay between the strategic caution of the Iraqi authorities and the normative activism of the American neoconservative administration vividly illustrates the political flexibility of the odious debt doctrine. The cancellation was not the result of a demand from Iraq, but rather the U.S.’s ability to impose its own normative framing on the community of creditors. Beneath the invocation of justice, a degree of cynicism was unmistakable: the objective was as much to facilitate reconstruction in line with the broader U.S. agenda of forced democratization in the Middle East as it was to ease the financial burden of occupation by preventing oil revenues from being used to repay creditors, many of whom were among the most outspoken critics of the military intervention. The doctrine of odious debt thus emerges as a flexible concept, providing a rhetoric of justice that can be used to delegitimize creditor claims considered unacceptable. By aligning positions and structuring discourses, odious debt offers a compelling argumentative framework capable of conferring normative legitimacy on unilateral decisions and situating them within a broader narrative of international justice.

Beyond solvency: the audit of odious debts in Ecuador

The revival of the Costa Rican formula of the odious debt doctrine finds a striking illustration in the Ecuadorian case. During the 2006 presidential campaign, Rafael Correa placed the denunciation of financial dependence and sovereign indebtedness at the heart of his political agenda, pledging to redirect public resources to education and healthcare. At that time, debt service consumed 38 percent of public revenues, while only 22 percent were devoted to social spending (Hurley, 2007). Following his election in November 2006, Correa declared his intent to contest portions of the external debt that had been contracted illegally or illegitimately by previous governments. To this end, Correa established the Comisión para la Auditoría Integral del Crédito Público (CAIC), mandated to carry out a thorough audit of all loans contracted between 1976 and 2006. The Commission convened for the first time in July 2007. Its mandate went beyond technical or financial evaluation: it aimed to examine the broader human and environmental consequences of Ecuador’s debt policy. The analysis focused on the irregularities in the issuance, renegotiation, and refinancing of loans, rather than scrutinizing the character of previous regimes.

What set the Ecuadorian approach apart was the decision to initiate the audit not in response to a solvency crisis, but as part of a broader effort to challenge the legitimacy of the country’s debt obligations. Contrary to the notion of an improvised or reactive default, the Ecuadorian experience demonstrates that default can be legally substantiated, methodically prepared, and strategically framed. The composition of the CAIC itself reflects this ambition to reconcile technical expertise with democratic legitimacy: it brought together four state representatives, six members from social organizations (including trade unions, environmental NGOs, indigenous groups, and feminist associations), and three international experts in sovereign debt.

Despite considerable tensions, notably the expulsion of the World Bank representative in April 2007, followed by that of the IMF in July, the audit was carried through to completion. It benefited from the support of a mobilized public opinion that saw in the audit the opening of a new chapter in the nation’s political history. This popular backing stemmed not only from the pluralist composition of the commission but also from the broader framing of the debt issue as part of a project of political emancipation. Unlike other countries in the Global South, such as Sri Lanka or Kenya, in more recent years, where debt-related contestation has remained limited to street protests, Ecuador succeeded in institutionalizing these demands through the establishment of an official audit. This ability to channel social unrest into a formal procedural mechanism gave the audit a political resonance that far exceeded its narrowly financial content.

The conclusions of the CAIC, published in November 2008, declared a portion of Ecuador’s debt odious and recommended a moratorium on the repayment of the Global 2012 and 2030 bonds. The Commission denounced the fact that the proceeds from these debts had been used to unfairly benefit specific groups of national and foreign creditors. It also criticized the coercive legal conditions imposed on Ecuador, including the waiver of sovereign immunity, subjection to foreign jurisdiction, and the transfer of private claims to the public treasury.

The proclamation of odious debt did not, however, trigger automatic cancellation. During the payment suspension, the Ecuadorian government implemented a parallel strategy: it secretly commissioned the investment bank Lazard to repurchase its defaulted bonds on the secondary market at steep discounts, in some cases for as little as 20 cents on the dollar. Through this operation, Ecuador repurchased $3.2 billion in bonds while spending only $900 million. The resulting savings amounted to $2 billion on the principal alone, with additional gains from avoided interest payments, for a total estimated benefit exceeding $7 billion (Toussaint et al., 2016). This maneuver enabled the government to retire over 90 percent of its outstanding bonds at a reduced cost. The debt reduction made it possible to expand public investment in infrastructure, health, and education. Between 2007 and 2017, social spending doubled, poverty fell by 41.6 percent, and the Gini coefficient declined by 16.7 percent. By 2010, debt service accounted for just 11.8 percent of the national budget (Bouchat et al., 2007).

The Ecuadorian episode represents a rare instance of sovereign default prompted not by solvency but by an explicit contestation of the legitimacy of debt contracts. It stands as a paradigmatic case in which a developing country challenged its foreign creditors without suffering major economic repercussions. Despite widespread international media criticism warning of credit downgrades and capital flight (Hounshell, 2008), Ecuador’s victory over its private foreign creditors was unequivocal: 91 percent of bondholders accepted the buyback offer at 35 percent of face value. The country faced no major sanctions and even regained access to international capital markets within a few years (Mansell & Openshaw, 2009). This outcome suggests a tacit endorsement by segments of the international financial community, including the U.S., of this mode of repudiation. From the standpoint of those committed to the norm of full repayment, however, this development was denounced as both “deplorable” and “deeply troubling” (Porzecanksi, 2010, pp. 268-269).

The Ecuadorian case thus reveals a complex, deliberate, and well-conducted sequence of events. While the initiative did not fall squarely within the realm of formal legal procedure, neither was it a purely political gesture: the audit constituted a politico-scientific body, established by a debtor state to evaluate the legitimacy of its debt obligations. By endorsing the 2008 moratorium, the audit sent a clear signal to investors that the issue at hand extended beyond questions of solvency and involved a fundamental political dispute. The introduction of an argument grounded in illegitimacy significantly altered the balance of power in creditor-debtor negotiations. To attribute the outcome of this confrontation solely to exogenous factors, such as the favorable context of the commodity boom, which temporarily reduced the country’s reliance on external financing (Roos, 2019, p. 308), would be to seriously underestimate both the strategic intelligence of the Correa administration and the technical sophistication of its bond buyback operation on the secondary market. Although favorable macroeconomic conditions played a role, they are insufficient, on their own, to explain the success of the initiative.

The Ecuadorian audit is also closely connected to another unprecedented initiative: the unilateral decision by the Norwegian government in 2006 to cancel €62 million in commercial debt owed by five countries, including Ecuador. This cancellation followed an international civil society campaign denouncing the illegitimacy of these claims. Beginning in 2002, researchers and activists from the Ecuadorian Centro de Derechos Económicos y Sociales (CDES), an organization committed to fighting corruption, launched an investigation into the so-called vessel loan case. This case involved a series of controversial credit agreements concluded by Norway during the Ship Export Campaign (1976-1980), which provided loans to several developing countries for the purchase of Norwegian-built vessels. In Ecuador, the CDES inquiry revealed opaque accounting practices that had caused the debt to rise from its original amount of $13.6 million to $50 million, without clear justification. Moreover, the four vessels that were supposedly delivered could not be located. CDES (2002) concluded that this loan “clearly falls within the category of illegitimate debts” and called on Ecuadorian authorities to demand its cancellation.

Norway eventually acceded to this demand through a unilateral decision, bypassing the Paris Club framework, and extended the cancellation to the four other countries that had received similar loans (Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2006). This move set a major precedent: it marked the first time that a sovereign creditor formally canceled a debt on the basis of a civil society campaign invoking the principles associated with the doctrine of odious debt. Announced at the height of Correa’s presidential campaign, the decision can be interpreted as an effort by Norwegian authorities to preempt reputational fallout and avoid further negative scrutiny, particularly if a newly elected Ecuadorian government were to formally endorse claims of odiousness.

A century after Sack formulated his treatise, it remains difficult to determine whether the Russian jurist would have endorsed such acts of repudiation or, on the contrary, condemned them as violations of the principle of continuity of sovereign debts. What is certain, however, is that he would have deplored the unilateral invocation of the doctrine by a state, rather than its application within the framework of an international court, as he had advocated. The dynamic initiated by the Ecuadorian audit and its political effects illustrate the continued vitality of the doctrine of odious debt, despite its lack of formal legal recognition. This emblematic case has inspired other initiatives, such as the citizen audit conducted in Iceland (Boudet, 2015, p. 390).

Preventive Diplomacy in Venezuela: Odious Debt as a Market Norm

The doctrine of odious debt has seen a marked transformation in its function and application in recent decades. Once primarily invoked retrospectively to legitimize a moratorium, it is increasingly being reimagined as a preventive tool designed to dissuade creditors from extending loans that could later be deemed illegitimate. This shift toward a market-oriented norm moves the doctrine further away from its original legal grounding and introduces significant conceptual complexities. Yet, for some analysts, it is precisely this anticipatory reinterpretation that could enable the doctrine to realize its full potential, not by retroactively justifying repudiation, but by preemptively defining the conditions under which a debt may be considered non-binding. This reframing raises a fundamental question: should the classification of a debt as odious await a political transition and be determined ex post, once a democratic government replaces an authoritarian one? Or, alternatively, can such a determination be made ex ante, based on the nature of the issuing regime itself? In the latter case, such a declaration would serve as a public signal that any debt contracted from that point forward could be rejected by a future democratic administration.

This transformation began to take shape in the 2000s with a proposal formulated by economists Michael Kremer and Seema Jayachandran after the Iraq War. They advocated for the creation of a body, either a U.S.-based tribunal or an international court, empowered to designate, ex ante, regimes whose debts would be presumed odious (Jayachandran & Kremer, 2006). Their initiative was part of a broader movement to reshape the conditions governing access to financial markets, against the backdrop of increasingly stringent conditionalities imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions, particularly under Paul Wolfowitz’s leadership at the World Bank. Implicitly, the proposal aligned with the neoconservative agenda of reorienting global financial flows to serve U.S. geopolitical interests. At its core was an attempt to structure sovereign lending according to a binary opposition opposing “allies” and “adversaries,” for instance, by prohibiting U.S. financial institutions from lending to regimes considered hostile to American strategic objectives. Framed as an effort to moralize credit and impose ethical standards on international lending, the proposal in fact reveals a political instrumentalization of sovereign debt, recast as an instrument of coercive influence in the service of U.S. hegemony. In this logic, the doctrine of odious debt is transformed into a unilateral tool of enforcement, reinforcing the escalation of U.S. sanctions policy against unfriendly regimes (Mallard & Sun, 2022).

The Venezuelan case is emblematic of this dynamic. On May 26, 2017, Ricardo Hausmann, a Harvard economist and former Venezuelan Minister of Planning, published an op-ed titled “Hunger Bonds,” in which he condemned Venezuelan sovereign bonds as immoral, arguing that they enabled an authoritative regime to rewards its creditors at the expense of its population’s well-being (Hausmann, 2017). Just days earlier, Goldman Sachs had purchased, at a steep discount, a batch of bonds issued by PDVSA, the state-owned oil company. Although purchased on the secondary market, these bonds, which had never previously been traded, resulted in an immediate $750 million increase in the reserves of the Venezuelan Central Bank, indicating a form of quasi-direct financing of the regime. Although Hausmann was unaware of the transaction at the time of writing, his op-ed was widely interpreted as a direct indictment of Goldman Sachs, triggering public outrage, media scrutiny, and protests outside the bank’s headquarters. This episode was followed by a sharp drop in the market value of the bonds, reinforcing the idea that the doctrine of odious debt can operate through moral and reputational performativity (Gulati & Panizza, 2021, p. 287). This case demonstrates that the impact of the odious debt doctrine need not rely on legal adjudication: the mere prospect of reclassification as “odious” was sufficient to shape investor behavior and affect market pricing.

The Venezuelan case illustrates the dual trajectory that odious debt has followed in the 21st century, situated at the intersection of legal principles and market dynamics. From a legal perspective, several studies have pointed to the vulnerability of the securities issued by the Maduro government, particularly in light of two principles recognized in key international financial jurisdictions. The first is the doctrine of the guilty agent: when a contracting party is aware that the debtor agent lacks legitimate authority to enter into the debt agreement, the contract may be rendered void. In the case of Venezuela, this reasoning could enable a future government to contest the validity of the loans contracted under Maduro, citing the fact that several high-ranking U.S. officials publicly questioned the legitimacy of his regime. On this basis, one could argue that creditors should have known that the Maduro government did not truly act on behalf of its principal, that is, the Venezuelan people. This argument recalls the stance taken by the U.S. after the Spanish-American War, when it refused to recognize the debt contracted by Spain in the name of Cuba. The second relevant principle is that of unauthorized transaction. Under New York law, any municipal bond issued without formal legal approval is considered invalid. In the case of Venezuela, several debt instruments appear to have been issued without ratification by the National Assembly, as required by the country’s constitutional process. If this absence of legislative approval were proven, it could provide grounds for a court to annul the bonds.

Alongside efforts to reinforce the legal basis of the odious debt doctrine, initiatives launched after the Iraq conflict to recast it as a market norm have also gained momentum. The objective is to turn the doctrine into an instrument for restricting authoritarian regimes’ access to international financing. The original proposal by Jayachandran and Kremer raised significant political uncertainties due to the difficulty of drawing a clear distinction between despotic regimes and fragile or failing democracies. This ambiguity risks subjecting politically contested regimes to punitive measures, even when they do not fully conform to the definition of despotism. To address these ambiguities, scholars have suggested developing a rating system to assess the odious nature of sovereign debt, modeled on the practices of credit rating agencies (Hausmann & Panizza, 2017). Unlike traditional credit ratings, which evaluate repayment capacity (Pénet, 2016), this system would estimate the probability that a given debt might be deemed non-transferable by a court to a successor government. It would operate along a continuum from repressive authoritarian regimes to fully democratic states, allowing for intermediary political configurations. However, the proposal raises significant ethical and legal challenges: chief among them, the difficulty of assessing a regime’s democratic legitimacy without reintroducing normative bias. The case of Venezuela clearly illustrates this problem: while some observers locate the authoritarian drift as early as the presidency of Hugo Chávez, others consider it to have begun only under Nicolás Maduro. To mitigate the influence of financial and political pressures, one suggested solution is the establishment of a non-profit rating agency, rather than a private or state-affiliated body (Pénet, 2017).

Critical questions remain as to how such a rating system would be incorporated into investment decisions: would it take the form of an official certification, a regulatory requirement, or a tool left to the discretion of market actors? Beyond these governance and technical considerations, the most fundamental limitation of this approach lies in its failure to address a more structural problem: namely, states’ structural dependence on financial markets and their enduring vulnerability to predatory lending practices.

Odious Debt and Predatory Lending in Greece

The preventive diplomacy framework outlined by Hausmann, Gulati, and Panizza ought to be expanded to encompass cases in which democratically elected states become trapped in cycles of over-indebtedness driven by predatory practices on the part of their creditors. In their formulation, the odious nature of a debt derives chiefly from the political illegitimacy of the borrowing regime: in both Iraq and Venezuela, the debts are deemed illegitimate insofar as the governments themselves lack legitimacy. This approach builds on the logic of the Cuban formula of odious debt, which anchors the doctrine in the character of the regime.

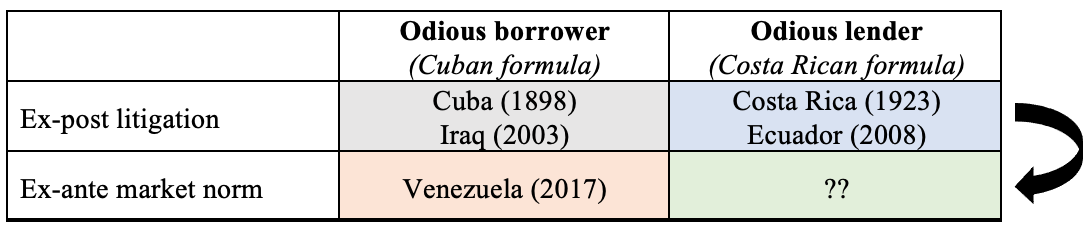

The final two sections of this article explore an alternative trajectory that envisions the application of preventive diplomacy in accordance with the Costa Rican formula, which places the main emphasis on the use of funds and the responsibility of creditors (see table below). In a global context where most sovereign debt is issued by democratically elected regimes, the relevance of the odious debt doctrine would be significantly enhanced by integrating the problem of abusive lending. Reframed in this way, the doctrine could serve as a safeguard against predatory lending practices, redirecting the analytical focus away from the political legitimacy of borrowing governments toward contractual dynamics, informational asymmetries, and the active or tacit complicity of creditors.

Table 1: Restating odious debt, a schematic overview

This shift in analytical focus resonates with contemporary debates on the dynamics of financial predation within democratic regimes. In 2023, of the roughly $97 trillion in global public debt, the vast majority was issued by democratic states (UNCTAD, 2024). In these contexts, over-indebtedness stems not only from excessive borrowing by governments but also from a surplus supply of credit pushed by lenders. This challenges the conventional narrative of the creditor–debtor relationship, which casts lenders as passive responders to sovereign borrowing needs. In reality, creditors frequently engage in aggressive solicitation strategies, at times manufacturing artificial demand for financing to support projects for which recipients had expressed no prior need. Since the major waves of liberalization in the 1970s and 1980s, abusive lending practices have emerged as a key driver of international financial instability. As early as 1976, Johannes Witteveen, then Managing Director of the IMF, cautioned against the growing activism of creditors in pushing states to take on excessive debt: “Commercial banks should not be so easily accessible that [...] this leads authorities to accumulate debts greater than what is desirable (cited in James, 2002).” His warning anticipated the debt trajectories later witnessed in Latin America and Southeast Asia during the 1980s and 1990s, and in Southern Europe during the 2000s.

The Greek case offers a paradigmatic illustration of the cycle of predatory lending, unfolding in three stages: first, aggressive creditor solicitation; second, the concealment of debt through complex financial engineering; and third, public sector bailout, each step contributing to the escalation of sovereign indebtedness (Pénet, 2018). The initial phase began in the 1970s with a surge in military spending following the return to democracy. Greece soon became the world’s second highest military spender per capita. The main beneficiaries of this arms buildup were French and German defense firms. In 2000, the French company Dassault secured contracts for Mirage fighter jets and missiles worth €10 billion. In 2003, Krauss-Maffei Wegmann signed a €1.6 billion deal to supply 170 Leopard tanks. Perhaps the most emblematic case was the €5 billion submarine contract signed in 2000 with the German conglomerate ThyssenKrupp (Daley, 2014). In 2015, a former Greek Minister of Defense was convicted and sentenced to prison for accepting €8 million in bribes linked to this deal. Over several decades, arms procurement played a major role in the build-up of Greek public debt. Had defense expenditures been in line with the European average, Greece would have saved nearly €150 billion, an amount exceeding the first bailout package implemented in 2010.

The second phase of the predatory lending cycle involves the concealment of debt through opaque and complex financial engineering. In 2001, Goldman Sachs offered the Greek government a €2.8 billion currency swap designed to mask part of its debt and thereby allow the country to meet the criteria for entry into the eurozone. The arrangement involved exchanging Greek debt denominated in U.S. dollars and Japanese yen for euros, using a historical exchange rate that artificially reduced the true size of the debt. As a result, €2.37 billion—roughly 2 percent of Greece’s public debt—was erased from national accounts (Armitage & Chu, 2015). The bank received €600 million in fees for its services. Greek officials, lacking full comprehension of the financial and legal intricacies, only later grasped the long-term risks of the transaction, which ultimately cost the state more than €5 billion due to the interest rate formula embedded in the contract. Creative accounting played a significant role in the causal chain that led to Greece’s insolvency a decade later. By offloading debt from the national balance sheet, the currency swap created the illusion of fiscal soundness, misleading investors and enabling a decade of unchecked borrowing in a country touted as the financial “locomotive” of Southern Europe. When the accounting fraud was exposed in 2009, just as Greece plunged into a full-scale debt crisis, some observers called for a debt restructuring, arguing that the responsibility for the unsustainable liabilities should be shared between reckless lenders and imprudent borrowers (el-Erian, 2012). Yet the opposite occurred. Once it became clear that Greece had overborrowed, public institutions were summoned to the rescue. Large-scale lending resumed with little interruption, the only difference being the shift in creditor identity, from private financial actors to official public lenders (Mallard & Pénet, 2013).

Finally, in May 2010, the Troika (the IMF, European Commission, and ECB) granted a €110 billion loan to Greece in exchange for the adoption of drastic austerity measures. The bailout, which violated the IMF’s own internal rules prohibiting loans to insolvent countries, can be interpreted as a continuation of predatory lending by other means (Pénet & Mallard, 2014). The Troika simply added debt to existing debt, despite clear IMF guidelines against lending to countries unable to meet their obligations. IMF economists had explicitly recognized that Greece’s debt was unsustainable and that the country would not recover without restructuring (Pénet, 2018). “They bear criminal responsibility,” declared Joseph Stiglitz in reference to the Troika, which lent massively to Greece primarily to ensure the repayment of French and German banks, then holding over 40 percent of Greek sovereign debt.4

The cycle of predatory lending is by no means confined to Greece. Many democratic states have faced similar strategies. Creditor activism in the sovereign debt sector (stage one of the odious lending cycle) recalls the aggressive marketing tactics prevalent in consumer credit markets. These manipulative practices are not merely the result of commercial exuberance; they are embedded within a broader debt regime structurally organized around the suppression of default. When the prospect of sovereign default is effectively neutralized or severely constrained, creditors no longer internalize credit risk. Instead, they operate under the assumption that any losses will ultimately be absorbed through public sector bailouts, reinforcing a cycle of irresponsible lending.

This is not to entirely exonerate borrowing states. Fiscal mismanagement and tax evasion, often tolerated or even facilitated by public authorities, have also played a central role. Yet sovereign over-indebtedness could not occur without the active complicity of lenders. Some deliberately promoted opaque lending practices, offering loans on predatory terms to financially unsophisticated public officials. In many cases, borrowing states were encouraged to enter into contractual commitments whose long-term implications they did not fully understand, while creditors operated with the near-total certainty that any resulting losses would be socialized through official rescue mechanisms. In such an environment, prudence is no longer rewarded, and speculative logics come to prevail.

Regulating Abusive Lending

Let us return to the question originally posed by Sack: should a debt be honored when it has been contracted in a context of predation, under terms clearly at odds with the public interest, and with the active complicity of the creditors? As cases of over-indebtedness increasingly result from abusive lending practices, the issue extends beyond the protection of borrowers. It calls for the construction of a regulatory framework capable of addressing credit abuse by confronting the predatory conduct of lenders head-on.

The doctrine of odious debt allows for a two-level response. The first, rooted in legal reasoning, involves linking this doctrine to existing mechanisms in the two main international financial jurisdictions: New York and England. These legal systems offer borrowing states at least two avenues of recourse against predatory lenders. First, the principle of abuse of rights enables the annulment of a loan contract concluded under conditions of blatant fraud, such as the proven corruption of a public official. Second, agency law imposes a fiduciary duty on agents to act in the best interest of their principals. When applied to sovereign debt, this principle implies that public officials are expected to act in pursuit of the public good. If a creditor issues a loan knowing, or having strong reasons to suspect, that it exceeds the state’s repayment capacity or undermines the welfare of the population, they may incur civil liability. These principles establish a link of causality and shared responsibility: the lender cannot be legally insulated from the social and economic consequences of their financing decisions.

However, the effective implementation of these principles faces significant legal hurdles. The main challenge lies in establishing the lender’s intent. It is not sufficient for a loan to be imprudent or to have produced harmful effects; it must also be proven that the creditor acted knowingly or with the intention to deceive. As several case studies, particularly those involving China as a creditor, have shown, the motivations of actors are often ambivalent, contradictory, or difficult to substantiate, which greatly limits the effectiveness of legal actions pursued by indebted states.

Beyond these ex-post legal remedies, arguably the most effective strategy would be to reorient the regulation of abusive lending toward a preventive framework by leveraging the conditionality mechanisms of the IMF. The Fund could assume a central role in institutionalizing a principle of creditor responsibility by supplementing its current focus on debt sustainability with assessments of debt legitimacy. A meaningful reform would involve making access to IMF resources conditional on a prior evaluation of whether the original loan was abusive. In this model, financial assistance would be granted only in cases where creditors had not engaged in predatory behavior. Such a shift would exclude reckless creditors from IMF financial rescue operations, while enabling borrowing countries to suspend repayment of debts tainted by abuse. It would mark a decisive break with the recurring pattern of socializing private financial sector losses through public bailouts. Currently, lenders operate with the implicit expectation of being rescued in the event of crisis, a dynamic that discourages prudence and fuels unchecked financial risk-taking.

Implementing a systematic evaluation of whether a loan is odious or abusive would hardly be revolutionary. IMF conditionality has long been a site of evolution, contestation, and reform since its inception in the 1950s (Sgard, 2023, pp. 22-48). Moreover, a range of institutions, including the OECD, already produce assessments on issues such as corruption, human rights, the rule of law, and states’ commitments to environmental and governance standards (Balachandran et al., 2018, p. 500). In parallel, the concept of “responsible lending” has gained institutional recognition, notably through the work of UNCTAD, which issued its Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing in 2012 (UNCTAD, 2012). These principles place specific emphasis on the responsibility creditor, stating that a loan can be considered legitimate only if it is granted under transparent, sustainable conditions and in accordance with the public interest. Though non-binding, these standards seek to rebalance the relationship between sovereign debtors and creditors by establishing clear norms of conduct.

Conclusion

The combined leverage of private law (through national jurisdictions) and multilateral institutions (through IMF policy) could support the emergence of a genuine deterrent framework against irresponsible lending. By introducing the credible prospect of debt repudiation or the non-enforceability of illicit claims, such a system would compel creditors to internalize the risks associated with their lending practices. No longer driven solely by reputational concerns or moral appeals, creditor behavior would instead be shaped by concrete exposure to financial loss. This evolution is not only desirable but necessary to restore integrity to the sovereign lending market and to encourage creditors to apply more rigorous standards in selecting the projects they choose to finance.

The aim is not to transform every debt dispute into litigation, nor to make the courtroom the exclusive space for regulation. Instead, the goal is to establish a system of negative incentives strong enough to deter high-risk behavior upstream. Containing the proliferation of odious debts would thus hinge on the exercise of creditor due diligence, applied proactively during the pre-contractual phase of the lending process.

One question persists: if private law mechanisms and multilateral institutions already offer means to regulate abusive lending, does the doctrine of odious debt still have a role to play? Many legal scholars are skeptical. In their view, existing principles of fair or responsible lending are adequate to rein in creditor misconduct, while the doctrine of odious debt is undermined by conceptual ambiguity, which has impeded its acceptance in customary international law (Choi & Posner, 2007). Its continued relevance, they contend, depends on its justiciability: so long as no court has formally recognized it, the doctrine will remain on the margins.

And yet, closer analysis suggests that the doctrine’s significance lies elsewhere: in its ability to offer a political language through which to contest and delegitimize debts perceived as illegitimate. The label of odious debt remains a powerful rhetorical device, one that delineates limits to the enforceability of debt contracts. A century after its formulation, the doctrine of odious debt finds itself at a critical juncture. To retain its relevance, it must evolve beyond its initial emphasis on the character of borrowing regimes and take into account the role of creditors, particularly those who act recklessly, or with predatory intent. The convergence of odious debt and abusive lending has now become a key axis around which future legal and political disputes are likely to revolve.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Institut d’Études Avancées de Paris (IEA), and especially Saadi Lahlou, for inviting me back for a one-month fellowship. The Institute’s supportive and interdisciplinary environment was instrumental in enabling this research. I’m also thankful to David Armando, Gordon Cumming, Pierre Gaussens, Michèle Lamont, and Vivian Loftness for their thoughtful comments and insights as this work developed.

- For perspective on the Algerian case, see Mallard (2021).↩

- Jean-Luc Mélenchon, “Dimanche, ma gauche peut gagner en Grèce”, January 20, 2015. http://www.jean-luc-melenchon.fr/2015/01/20/dimanche-ma-gauche-peut-gagner-en-grece/↩

- “Paris et Washington s’affrontent sur l’annulation de la dette,” Le Monde, September 9, 2004.↩

- “Stiglitz on Greek Tragedy,” BBC, 30 June 2015.↩