Acknowledgements This research project and related results were made possible with the support of the NOMIS Foundation.

1. Communities of Knowledge and Practice

Collective intelligence (Malone & Bernstein, 2022) is the product of communities of knowledge: a group of people who share interests, communicate, and cooperate to produce new knowledge. Often these communities are also "communities of practice" (Lave & Wenger, 1991) who collaborate to achieve common goals. In fact, productive communities are communities of knowledge and practice (CKP) which, through common practice, create and manage knowledge, know-how and the resources necessary to deliver.

These communities can vary from very small (two persons) to vast (a scientific domain, an industry sector...); what matters is the ability to benefit from the exchange of views, the distribution of perspectives, and the capitalization of experience. Although that is not indispensable, these communities are often structured, with rules of communication and practice, social contracts 1 that bind members, and common tools. These facilitate constructive processes such as exploration, conceptualization, explanation, discussion, etc., which require interaction between several sources of knowledge. They also facilitate building trust and common projects, as well as capitalizing experience, providing gateways for access, and creation of reputations by peer review and gossip. All this lowers transaction costs for cooperation, and therefore makes a community of knowledge a proto-organization that is fertile ground for the emergence and growth of productive organizations.

Most domains of activity have, to some degree, their community of practice. Usually these include some "official" organization of representatives (e.g. union, syndicate, association, league, alliance, society...) but the community itself is protean, with blurry boundaries, and is rather identifiable either by insider knowledge, or some specific common events where most members meet (annual conferences, trade fairs, jamborees, etc.) or some common resources such as journals, mailing lists, iconic meeting places, directories, etc.

Practicing collective intelligence requires exchange of ideas, transferring knowledge and know-how, sharing resources, and some division of labour. It also requires some capitalization of the "culture" of the group, which includes knowledge, know-how, social capital (the links of the members with people inside and outside the community), as well as the physical artefacts that are used in the activity of the group, such as tools and other material resources (aka "material culture"). But a primary need is to identify the members and institutions of the CKP, to be aware and stay up-to-date with its current stakes and interests, and to get access to key members, gatekeepers and resources.

In short, to benefit from a community of knowledge or practice, it is essential to know who is doing what, who knows about what, and how to access these persons or entities. It is also essential to be identified and reachable as a potential partner and resource in the community by signalling the right thing in the right place.

In small groups where members know each other and meet physically, such as a sports team, a gang, a research lab, a tribe, an enterprise, or a school of artists, the transmission of culture is usually direct, starting with "observational learning" (Bandura, 1977). Lave and Wenger described the "legitimate peripheral participation" process by which novices gradually acquire the culture; in that process, the novices also gain a network of personal relations and some knowledge of who is who. First by observation, then by acting under close supervision, and finally by acting autonomously among peers (Lave & Wenger, 1991). This process is similar to the way humans learn their own culture by hanging around, watching and participating, a process by which we learn both know-how and the attached values, "intent community participation" (Paradise & Rogoff, 2009).This includes creating and learning formal as well as informal or "tacit" knowledge (Nonaka, 2005; Polanyi, 1967; Reber, 1989), as well as learning the values, norms and habitus of the community.

While formal knowledge can be expressed in symbolic language, stored and transferred, tacit knowledge (such as riding a bicycle or being a good host) are embodied competences that require experience and practice. This is learned by doing, in collaboration with mentors and peers. It requires access to the activity, which is obtained by being vetted and introduced, through networks. It is a gradual process where "social contracts" are built. A social contract is gained, developed and maintained by demonstrating one's capacity to play one's role as expected (Lahlou, 2024), which requires access and practice.

As no single member can embody the totality of a culture, knowledge and know-how are distributed over the community. Nevertheless, members know "who knows what"; which Roqueplo calls shifted knowledge ("savoir décalé": Roqueplo, 1990). Therefore, members can access the knowledge of those who have it, through their proxy. This information retrieval system was discovered as a method of "self-management of cultures", operated by the councils of elders among plain Indian tribes; those elders retrieved the information stored in the group ("tribal storage") when discussing cases (Roberts, 2016). One of the elders usually already had direct relevant experience, or knew someone who had direct relevant experience, or knew someone who knew someone etc. So, by proxy the relevant knowledge was retrieved.

Narratives ("stories") are an efficient way of transferring knowledge, shaping interactions, and communicating expected behaviour (Bruner, 1991; Hamby et al., 2016; Patriotta, 2003). Storytelling facilitates anchoring the knowledge in the experience and culture; furthermore, it comes with a human interaction that seems to be a very important element in the acquisition of knowledge. Humans give great importance to the source of knowledge, its credibility, prestige, cognitive authority but also more generally trust (Hovland & Weiss, 1951). The fact that knowledge is generated within a group seems to be important for humans, who are very social creatures, prone to influence (Cialdini, 2009; Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Deutsch & Gerard, 1955; Moscovici & Personnaz, 1980; Parsons, 1963) and, even more than other primates, to imitation (Whiten, 2000; Whiten et al., 2009). More generally, humans have set up many "installations" designed with the purpose of knowledge transmission, including instruction, supervised experience, etc. (Lahlou, 2017: 181-262)

While knowledge transfer occurs naturally within small groups that meet physically, experience shows that transmission is more difficult among larger groups, especially if they do not meet in person. "Knowledge management" started as an effort to leverage technologies to collect, store and transfer knowledge, including tacit knowledge (Earl, 2001; Ermine, 2010; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Tsoukas & Vladimirou, 2001). Knowledge management is now an established discipline with over two dozen academic journals (Serenko & Bontis, 2022); it focuses mainly on organizational knowledge. Many tools, including digital, have been used, which tend to formalize the knowledge into information that is stored and retrievable. These tools are usually set up by organizations that try to capitalize the knowledge of their employees, or inter-organizational knowledge relevant to their endeavour.

Nevertheless, attempts to formalize knowledge management have met limited success, because what matters is the community of practice with the interpersonal relations attached to it, which, as highlighted above, are important to motivate participation, learning, and sharing. Even in our age of internet and easy access to information, the role of interpersonal networks remains paramount. In fact, it turns out that the cognitive overload resulting from the massive information available may increase the importance of networks as a filtering system to choose what information to use. In his introduction of the Cooperative Buildings conference in 1999, Herbert Simon mentioned (oral communication) that he did not read newspapers, he did not need to: on arrival at work, his colleagues (who had read the newspapers) would tell him what was important as they casually talked over coffee, and therefore Simon was kept well informed. But of course, tapping in such sources, that filter the information according to your needs in a relevant way, supposes that you do have access to the relevant community.

In fact, even (and perhaps even more) in our age of massive information, online resources, databases and browsers, the successful search of essential information and resources (e.g. funding, job positions, projects, partnerships etc.) happens through networking in such communities. This is because communities filter, assess, and mobilise the nature and quality of resources.

So, having access to a knowledge and practice community is a great resource. Especially in times of information plethora and cognitive overload, the CKP is essential to find the right information and the right partners.

In short, to foster collective intelligence and the construction of fit partnerships and organisations, with the proper resources, we need to support knowledge and practice communities where participants can find interested parties to exchange views, discuss, share experience, transfer, and build knowledge and resources. These communities are more than a mere repository of information, they must put people in contact; they should facilitate the transfer of knowledge in suitable formats, e.g., stories, experience sharing, live meetings, etc.

Unfortunately, as said above, it is notoriously difficult to manage CKP top-down, and many attempts by organizations to create tools for knowledge management fail. This recurrent failure accounts for the relative loss of interest in knowledge management, after a period of glory.

An issue is that knowledge is a stake for status and power (Crozier, 1963), and knowers are reluctant to share it without some benefit. This can be overcome to some extent if participants are officially credited for their contribution, as was done in the Xerox Eureka system (Orr, 2016), or if participants feel their contribution is useful and can make a difference to others in the community.

Managing knowledge in an entity whose mission is to produce it (e.g. a research community, teaching community, media community...) is especially delicate, because of the necessity to manage the products (documents) and the processes and resources that produce them. The CKP management should not be confused with the management of documents. It should focus on :

- the expertise ("who knows what"),

- the processes and structures (e.g. projects, organisations, sources) in which the production is embedded,

- the conditions (time, place, formats, cost) to reach the person/team/resources within the actual community,

- the degree of validity of the information (freshness, reliability...).

Because in such CKP the boundary between content and processes is blurry, the management tools must be flexible.

Another key issue is the burden on participants to fill in the data collection instruments, which is felt as an extra cost on top of the daily job, with little reward and personal interest. This is akin to the tragedy of commons: participants would be happy to have a good information system but have little incentive to contribute. Among the seven principles for cultivating communities of practice suggested by the seminal authors (Wenger et al., 2002), we found that providing value to users (idem: 49-50) is essential. But we also found it essential to minimize the cost of contribution.

Finally, paramount is the issue of a community being a group of people, and not a set of documents, so the idea that an IT system could replace the community is wrong, even though the organization may wish to do so to get managerial control (Cox, 2007; Orr, 2016).

Therefore, the instruments designed to support CKP should be oriented towards the community and not just towards information per se. That is what the netboards are: they are designed as a directory to resources in the community rather than a simple repository of information. Instead of trying to capture all the knowledge from the community members, it signals the resources from different perspectives (person, team, project, expertise) and facilitates access to them. Those members who want to share more on the netboard can, but that is not compulsory.

2. Netboards

While in the past communities of knowledge and practice (CKP) connected essentially by face-to-face interaction, they are now global and communicate with digital means. They have also considerably grown, in the diversity of their activity, as well as in complexity and speed of evolution. This increases the orientation problem, where one has difficulty to know who does what, and how to get access, which, as we saw above, are essential to participate in a KPC and benefit from participation.

The instruments that we set up for the above purpose of participation, the netboards, are designed for hybrid (in person and digital) CKP. In what follows, we give a brief history of how we came to set these up, then we describe their functionalities, and what we learned from using them. A netboard is a portal offering interactive catalogue/directory that contains brief structured descriptions of the objects relevant to a CKP, or "items" (persons, projects, concepts, tools, documents, cases, stories, procedures, calls, rules...). Each description (the "page") is created and maintained by an "owner" who is the "contact" for the item. It contains, apart from the brief description that acts as a showcase, a series of structured standardized descriptors that facilitate searching and sorting, and a feature to contact the contact using the netboard as a proxy, without leaking any personal information. This hybrid structure combines aspects of a website, a database, a content management system (CMS), a directory and a message board. It addresses essential functions of a CKP self-management (find who does what, get access), while solving some of the main issues of the classic instruments, namely keeping the information up to date and respecting the diversity of communication policies and the personal data of participants.

The design of a netboard must of course be adapted to its specific CKP, and therefore in the detail it will change, and evolve. Nevertheless, in our experience some generic principles seem to apply to all netboards, which we describe below in section 5, "lessons learned". Before that, we describe concretely some netboards made with the version 1 of our IT platforms.

3. History: facilitating research during the Covid 19 Pandemic, and beyond

In February 2020, the Paris Institute for Advanced Study was hosting, with the European Research Institute for Chinese Studies (EURICS), Professor Xiaobo Zhang who was studying Chinese small and medium enterprises. Zhang witnessed the massive impact of the Covid 19 virus on them. At a time when Europe was still unaware of the pandemic, Zhang's work made us realize that the epidemy would soon have major societal impacts worldwide. Therefore, the world needed a tool to enable the scientific community to mobilize its collective intelligence very fast, to prepare the societies to deal with the upcoming problems. We organized a conference 2 and fostered Professor Zhang's essential warningto French authorities, but clearly the virus needed a worldwide response at the scale of what was clearly going to become a pandemic.

A consequence of the way we do science, where publication is essential to researchers' career, is that dissemination of results happens through publication. But the peer-review system is so clogged that it often takes months or years until results are published in a paper (Taşkın et al., 2022), which means an even longer delay from the moment results were found. And an even longer delay from moment the research started. This lag is problematic when society needs to react fast, as in a pandemic or another type of potentially catastrophic process, such as the current transitions.

Another issue, resulting from the way we created competition between scientists for funding and resources, is that collaboration is rather easy to set up at the very beginning of projects, especially when people get together to obtain competitive funding, but later teams and organizations tend to get into competitive mode as soon as the projects are started. Therefore, it is crucial to facilitate contacts early on, when collaborations may start; in fact, we should facilitate such contacts all the time. As we saw in the first section, this means the CKP must have continuously operational, and up-to-date, instruments that provide a complete cartography of who is doing what, and facilitate access to one another. In February 2020, that was not the case of the worldwide social science community that should have been working together on the pandemic to advise decision-makers and the civil society.

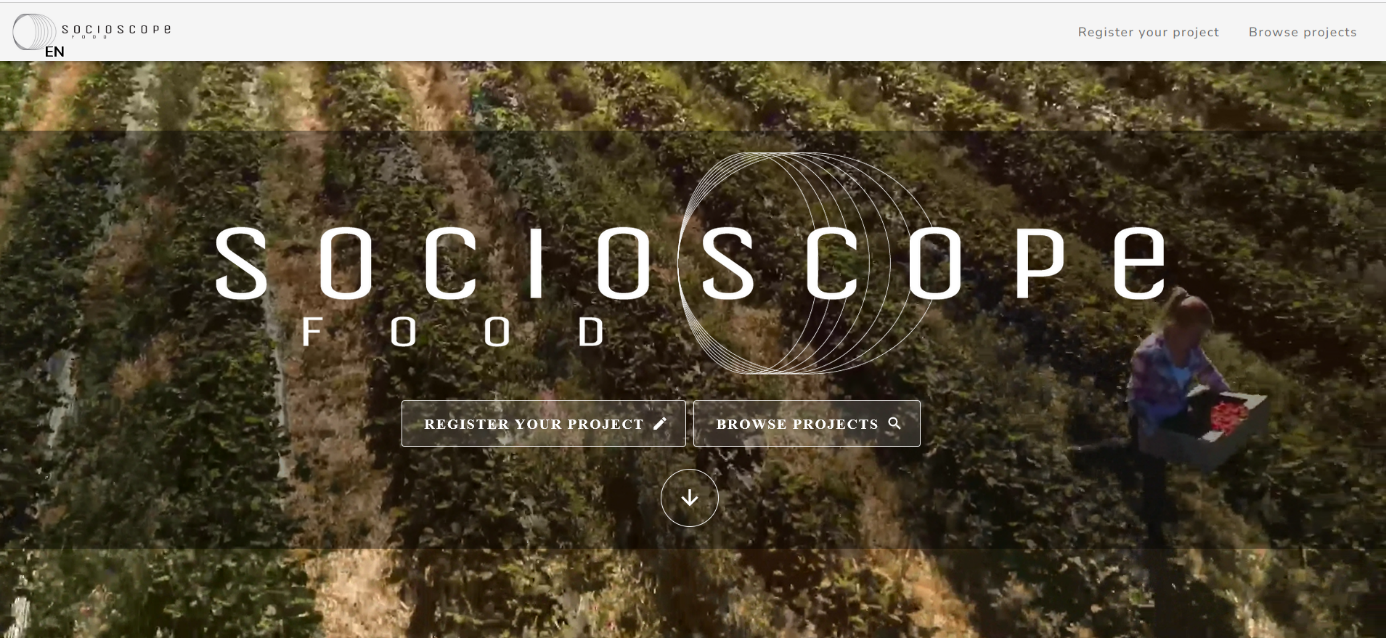

We decided to set up a platform that would foster collective intelligence and collaboration worldwide. We cannibalized the IT infrastructure of another platform we were preparing, ASTR (the Advanced Studies Transdisciplinary Review) and, as early as April 2020, WPRN (the World Pandemic Research Network), was born and its netboard was operational online at wprn.org. It looked like a website, was searchable like a database, anyone was able to set up and curate their own webpage easily, it enabled getting in touch like a directory, and it served as a gateway to all resources, instead of capturing users in its net -as do social networks that are commercially motivated. It was fully GDPR compliant, open, free, and under Creative Commons licence, publicly funded by the French Ministry of Research (MESRI). The first example of a "netboard" was born.

We then created three other netboards: The Socioscope (in 2022), GovernU (2023) and IPSP (2024). They all share the same structure while addressing different CKPs. The Socioscope was first intended to address a CKP in food transition (with the project of extending it to other major transitions). GovernU was about management innovation and good practices and ended to be discontinued as, although technically operational, it was never fully used because of the lack of permanent secretariat. And IPSP is the International Platform for Social Progress, a CKP to improving the functioning of societies in the face of the triple challenge of environmental degradation, growing inequalities and the renewal of forms of democratic deliberation. The next sections of this paper show the common structure of these four netboards and the lessons learned during their creation, development and maintenance.

4. The netboard as an installation supporting CKP

A netboard is an infrastructure that combines in a one-stop-shop a series of functions necessary to participate into, and benefit from a CKP. It enables finding who does what, getting in touch with them directly, and being signalled joiners to the CKP. It enables signalling one's activities and interests to others. Furthermore, the netboard enables managing the community, by providing a "back-office" where the animators of the community can extract information, comment and moderate the contents, get in touch with the participants, organise events, broadcast content, etc.

There are two entries to a netboard, that provide either of its two main and symmetrical functions. One, the page creation, enables participants to describe their item by building their own page as a showcase.

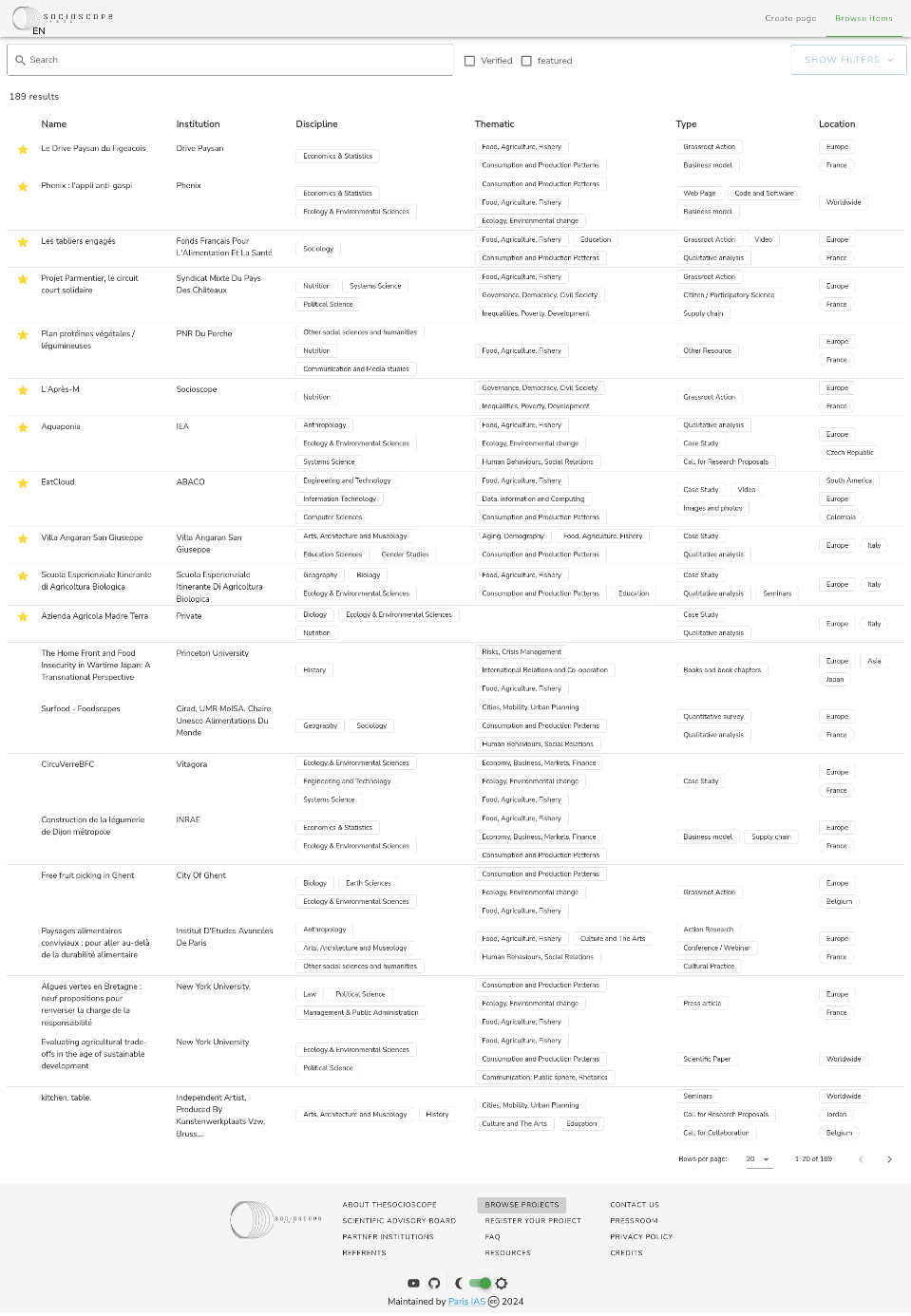

The second way of using the netboard, the browsing, enables users to find what they search and engage exploration and contact. With a simple query, as in a browser, they get a list of the matching items in the netboard. The list (of relevant items) is the default presentation mode in the netboard. The list is a very powerful cognitive tool (Goody, 1977).

The home page looks like a regular website, and the navigation id designed is such a way that the user does not need to learn any new skill to use the netboard. What every internet user already knows (to click on links, to choose an item in a list, to enter text in a search bar) is enough. The navigation is very similar to popular browsers and merchant websites.

In fact the website, from the users' perspective, feels more like a merchant platform, where one can shop for goods, than like a classic website. Except that here the user is searching and collecting items in a non-merchant perspective, rather for knowledge and networking. While this convergence with merchant websites was not intended in the beginning, our quest for efficacy, smooth user experience and IT efficiency produced some evolutionary convergence. So, we realized ex-post that we had designed a non-profit version of merchant platform. Interestingly, this convergence was also technical, since we came to use the same type of advanced cloud-based architectures and services.

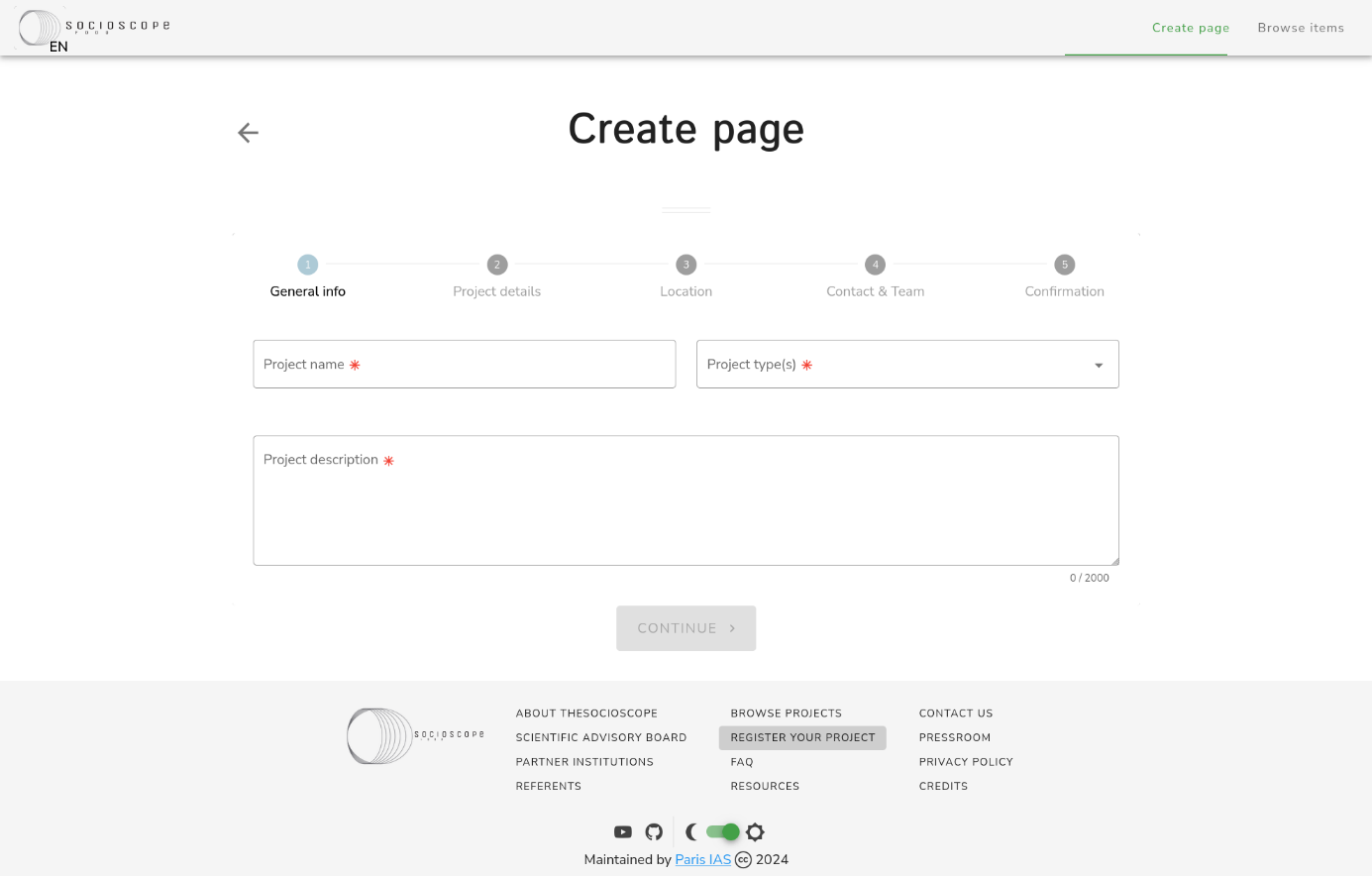

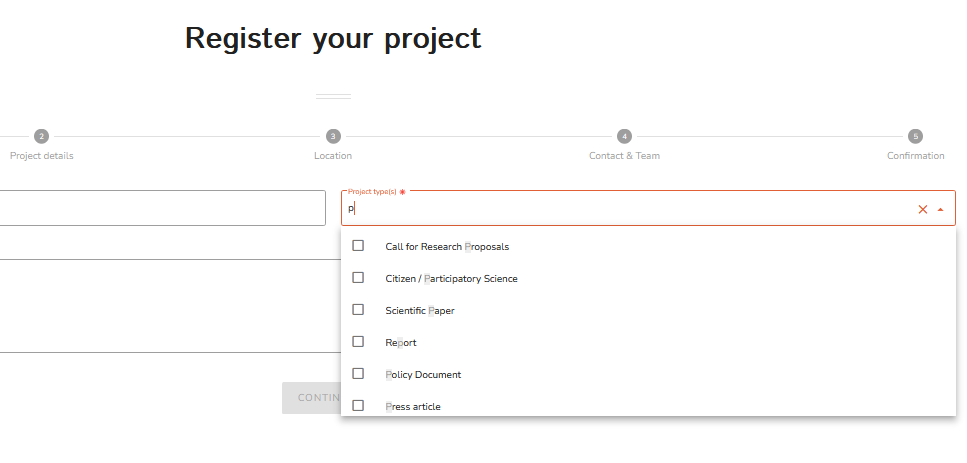

4.1. Creating a page for an item

The creation will lead to a series of screens where the participant fills form boxes that will describe their item. The different steps may vary depending on the type of item registered and their type of owner. They all consist at least of:

- a title

- a short full text description;

- a series of closed variables (e.g. type of item, discipline, location...);

- links to further detailed information (typically the owner's website and further documents);

- an optional link to a video;

- information that will enable further communication (name of item owner or team, email address obfuscated by a server-side contact feature).

This process ends with a verification of the email address and the publication of the page. The participant then receives a link to their page, and the credentials to edit it directly. In the course of the process, a series of automatic checks protect the netboard from bots and other online dangers, and collects the proper legal authorizations regarding publication, as the page is licensed under Creative Commons licence 4 and visible freely and publicly. The item automatically gets a tiny permanent URL for its page, an official identification number and a creation timestamp that are all displayed on the page. This timestamping serves IP issues, as the creation of an item by a given author can be officially dated for attribution of authorship.

While the page is immediately published, it is also automatically flagged as a new item to the secretariate of the CKP and to the referents, who may exert edit and initiate communication with the participant, who is now officially part of the CKP. As a new item and until it is "validated" by the secretariate or referents, it will appear in the bottom of the default list when browsing items.

The pages and boxes are very simple and straightforward. The closed variables are accessible through drop-down lists. Here, in Figure 4, a screen of the page creation process for a specific type of item "Projects" in the WPRN netboard.

If the abstract describing the item in full text is ready to cut and paste in the creation box, the whole operation of page creation takes less than 5 minutes. The page is immediately visible, and editable. The owner of the item can also delete the page at any time.

4.2. Browsing items

The second entry to the netboard is the search and exploration.

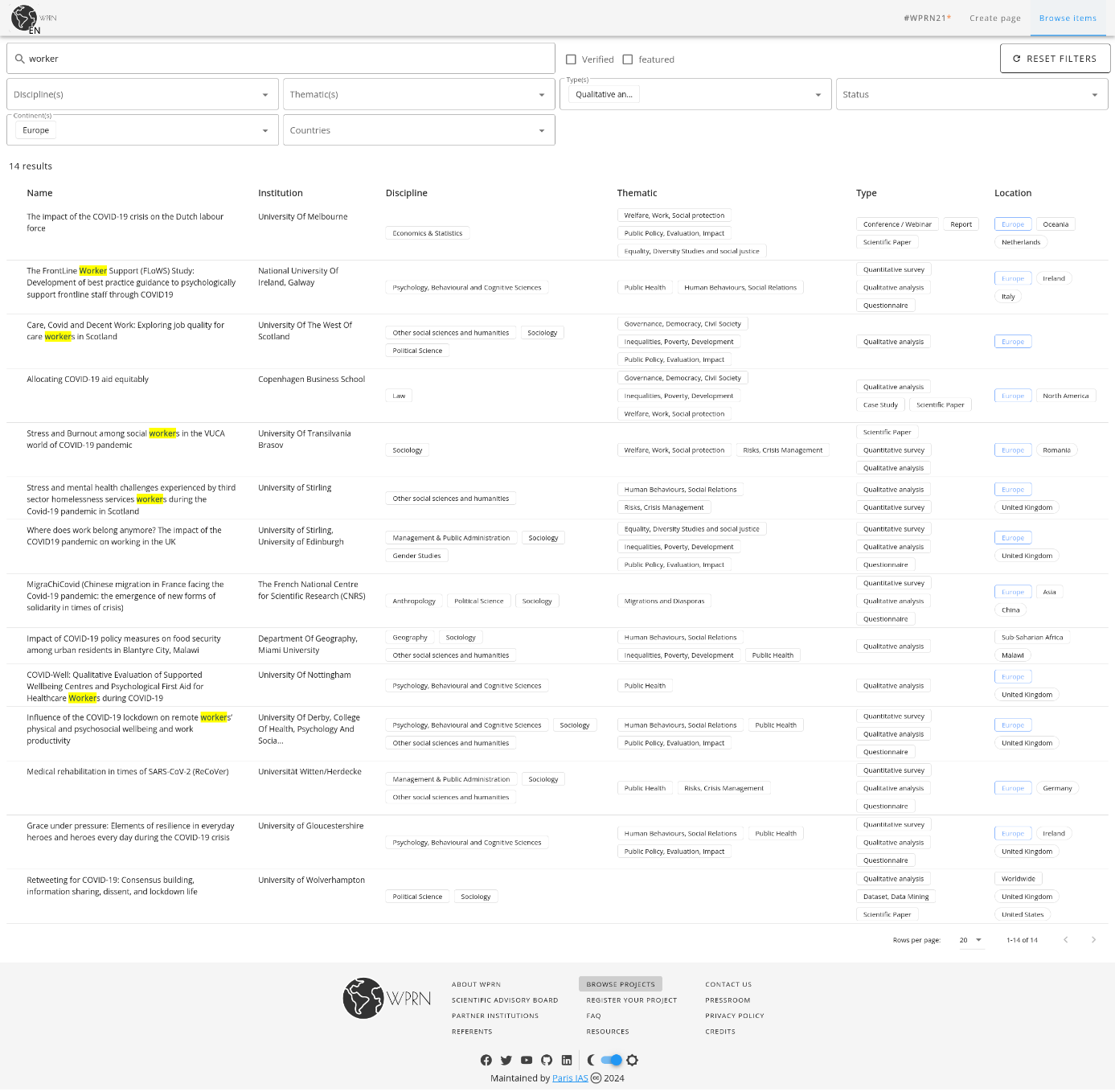

The interface presents lists of items, as a web browser would, based on the search prompt. Unlike with many web browsers, the search can combine terms for search in full text of the pages and the variables. For example, the search on "workers" combined with the geographical zone of "Europe" and "qualitative analysis" provided 14 results in the WPRN netboard.

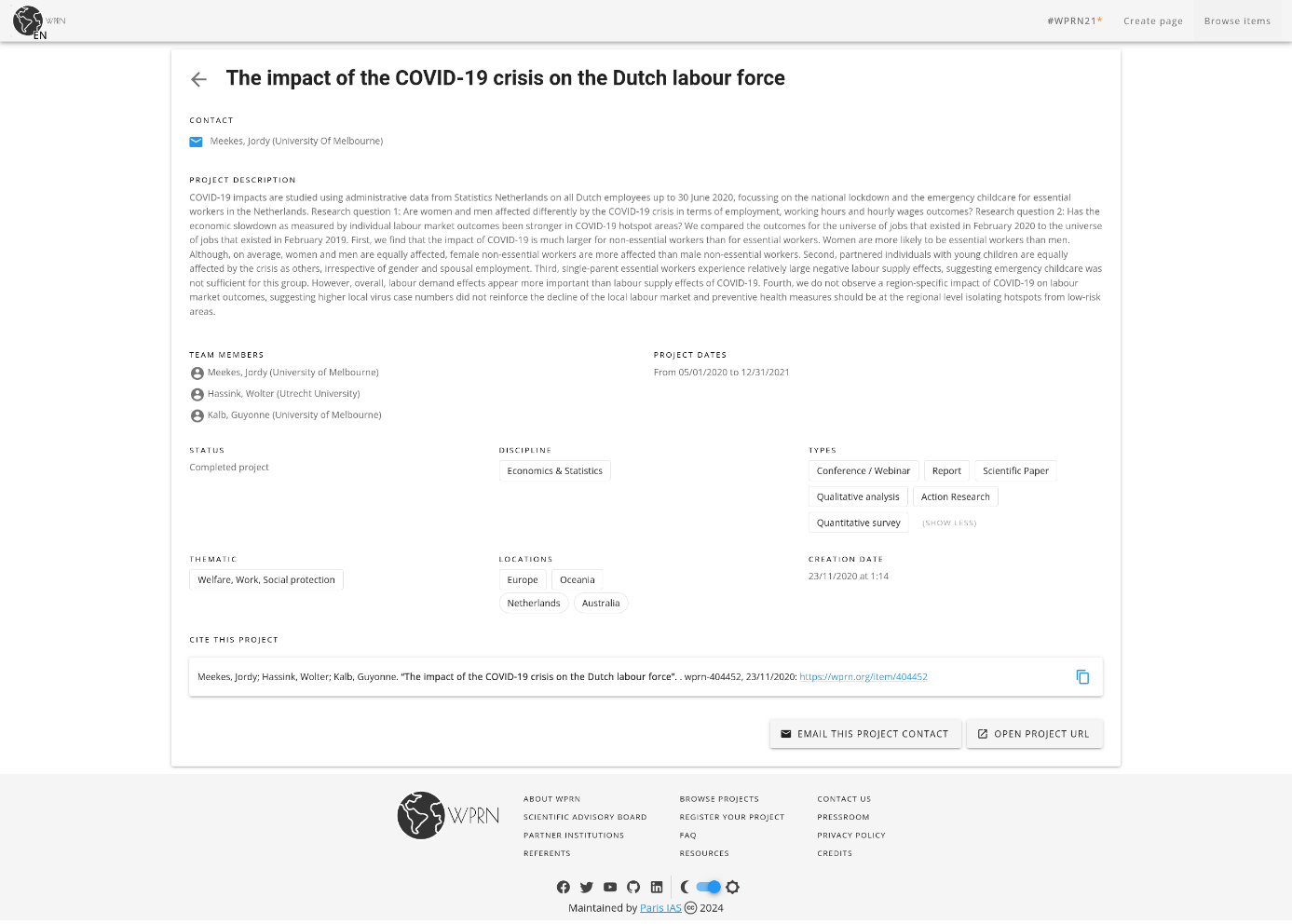

The items appear as a list. Each item in the list is clickable, and links to the page of the item. The page contains a description of the item (in the example below, a survey).

The page of the item also contains a list of the variables entered by the item owners when they created the page.

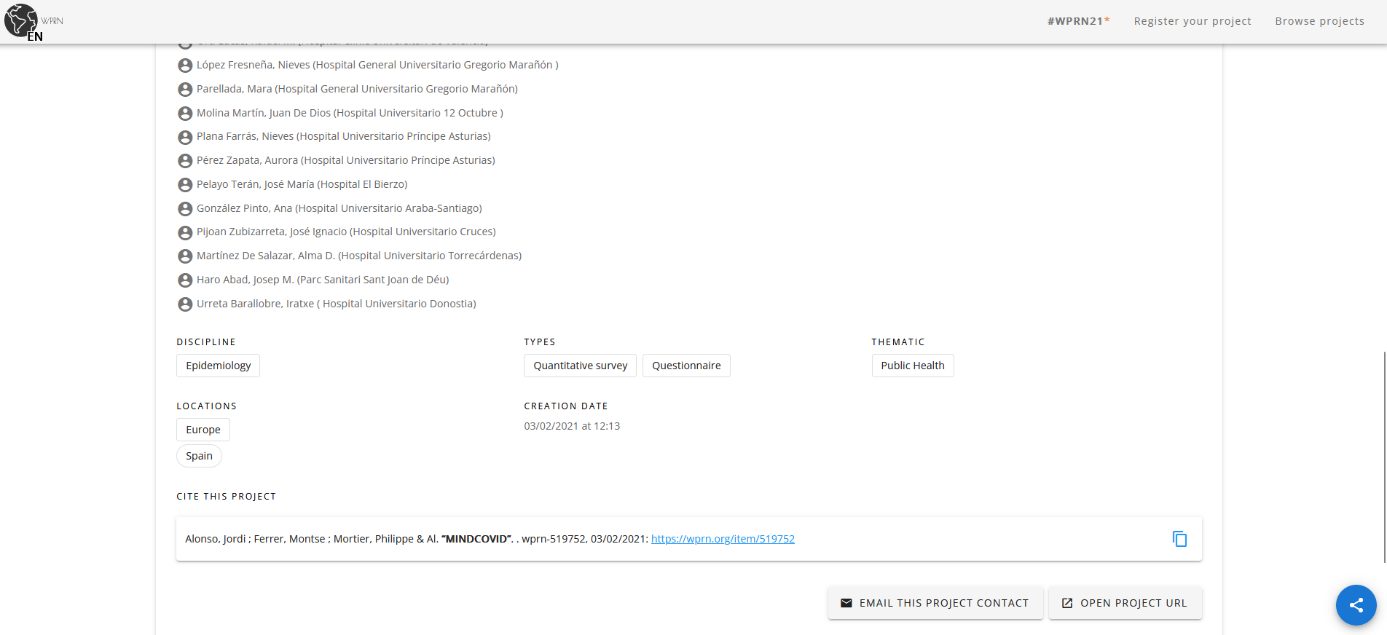

On Figure 6, for example, this page of the item includes a list of the participants in the project.

Note the two buttons on the bottom right. One includes a link to the item's own URL, here leading to the website of the owner organization (outside of the netboard), and the other is an email link to contact directly the owner of the item.

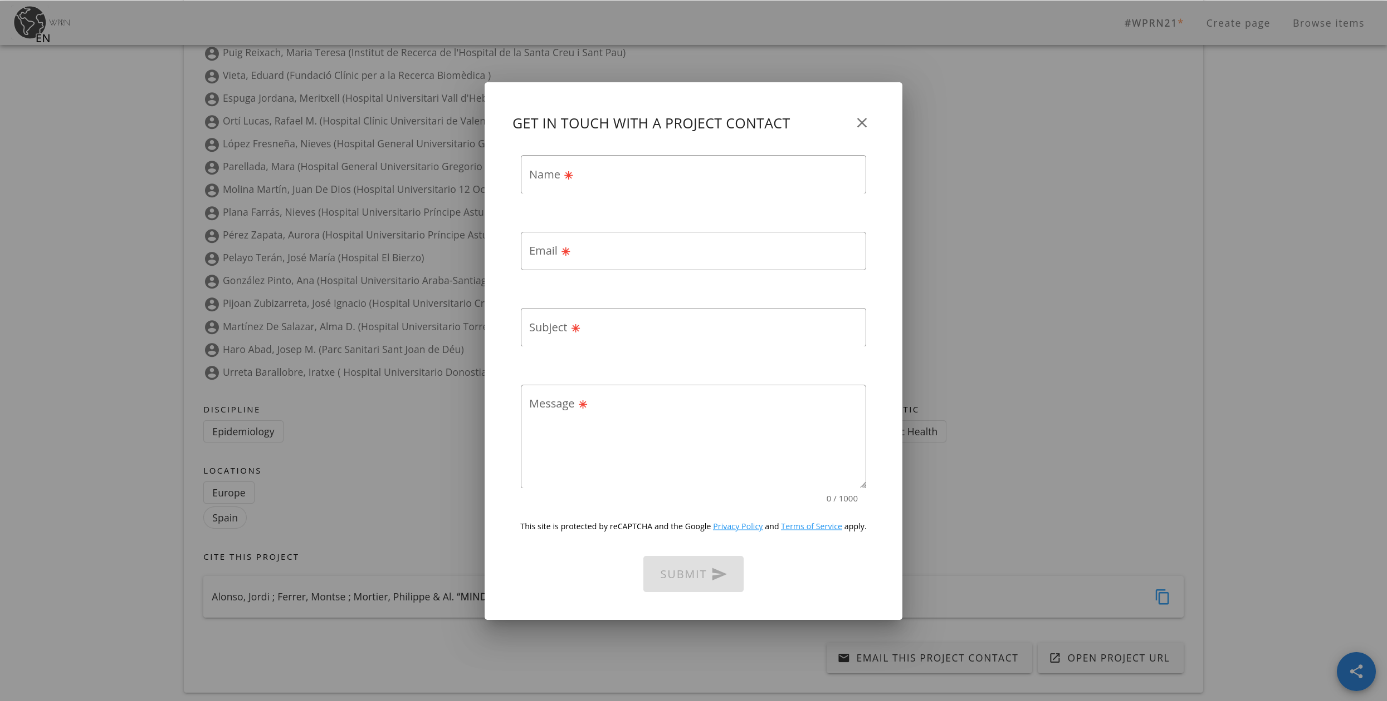

Clicking on this link opens a "contact" page. On that page, the address of the owner is hidden. The owner will get the message in his own email system (outside of the netboard) and will therefore be able to correspond directly with the sender, outside of the netboard.

As is visible in this example, the netboard only acts as a shop window that puts participants in contact with users. The netboard showcases items, in a format that is fully controlled by the item owners. Through the item's netboard page, the netboard brings traffic to the owners' own pages and websites, outside of the netboard. So, the netboard puts participants in contact with interested parties, but from there onwards the communications initiated take place outside of the netboard, usually through the participants' preferred tools (email, instant messaging, etc.)

This light-handed approach contrasts with the capturing policy of merchant websites and social media platforms (of which the netboard is very close in terms of display, search functions and interface fluidity) who strive to keep all communication exchanges within their own system in order to keep users captive. The netboard philosophy is non-merchant: it is to provide service to the CKP rather than to exploit the CKP as a source of profit.

Furthermore, experience shows that users tend to use their own messaging system to archive and capitalize transactions with other parties. Therefore, it would be a problem for users to have to connect to the netboard to monitor interactions with a specific contact. Of course, this can appear as a limitation to those who use the netboard to monitor CKP, but we designed the affordances precisely to safeguard the privacy of exchanges between users from the oversight of third parties.

5. Lessons learned

5.1. Good technology is not enough

While the information technology infrastructure is essential, it must very clear that the netboard is not the CKP management system, it is just a component of it. What we want is not a tool, but a good CKP community, to support the activity of its participants so that ... they participate in the creation, management and dissemination of knowledge good practice, and in the avoidance of bad practice. The netboard is designed as a support to the CKP, not as a knowledge repository (even though the netboard is also a knowledge repository).

Perhaps we should clarify what we mean by knowledge in this context. Knowledge is a part of know-how. For example, if you want to make chocolate, you must know how to recognize the cocoa tree, where to cultivate it, how to extract the cocoa and to transform it into chocolate. At each step, you must identify objects, states, and know what transformations to apply to them, with what tools, etc. Expressed more generally, know-how is "the ability to perform an action to achieve a goal. [it] comes from having knowledge about affordances and what to do with them to achieve the goal." In contrast with know-how, knowledge is the "ability to describe and recognize categories of objects." (Lahlou, 2024). Knowing what does not necessarily imply knowing how.

So, a CKP will share descriptions of objects and procedures, in such a way that know-how in the given domain (and the corresponding knowledge) can be transmitted between participants. What we know of CKP, as said above, is that the mere dissemination of this knowledge in the form of "information" (that is, documents describing knowledge in the form of text, image, sound etc.) is not enough, and that we also need people to get in contact so that the information can be explained, illustrated, commented etc. though direct and interactive communication. In other terms, the knowledge must be socialized, and can only thrive within a CKP. Hence the activity that the netboard must support, foster and sustain is both an activity of information management (creation, display, publish, search, find, update...) and an activity of community management (labelling of persons, organizations and other relevant social entities, fostering communication between them).

Here is our experience, mainly based on the netboards of WPRN, The Socioscope, GovernU and IPSP, which have been operating respectively since 2020, 2022, 2023 and 2024.

It is important to note here that WPRN was trying to connect people and structures that were not an existing CKP, but rather a series of local communities and entities who were potentially interested to become such a CKP, at least momentarily. This requested an important work of binding and legitimating this CKP, a political work that was undertaken by a few prominent figures, led by Olivier Bouin, the president of three international networks (EASSH, NETIAS and UBIAS). Indeed, the legitimacy of a CKP is an important factor when reaching out for new members. An international scientific board was constituted, and a hundred "referents" experts of the field (university professors and leaders of main national and international research institutions) were incorporated as a larger peer board that would be available to review and comment the content of the netboard as it grew up.

As a result, WPRN as an organisation was vetted by the International Science Council (ISC), the International Panel for Social Progress (IPSP), the European Alliance for the Social Sciences and the Humanities (EASSH), the Foundation Maison des Sciences de l'Homme (FMSH), the Network of European Institutes for Advanced Studies (NETIAS), the international network of University Based Institutes for Advanced Study (UBIAS), the Union Académique Internationale and several French research institutions. The WPRN netboard soon reached 500, then 1000+ research projects ("items"), and enabled scientists to set up collaborations at the early stage of project design. It facilitated free and worldwide exchange of information. It was also the instrument that supported the creation of the first conference on impact of the pandemics on societies, #WPRN21 3. WPRN was the prototype of "netboards", an original multisided platform that supports knowledge communities.

Our communications officer, Solène de Bonis, set up a secretariat that monitored communication with participants, set up the reports broadcast to the community, contacted potential participants to enrol them in the netboard, respond to questions, etc. This was a full-time equivalent (FET) for the first 6 months, and then 0.5 FET, on top of the computer scientists developing the infrastructure under the supervision of Paris IAS's Chief Technical Officer and IT architect, Antoine Cordelois, and the management board, essentially the two lead coordinators (Saadi Lahlou & Olivier Bouin). Paris IAS's communication officer and a few freelance writers worked on the reports and newsletters; a postdoc, Maxi Heitmayer, organised the international conference which used the netboard as an infrastructure to publish the presentation videos, which were put online two weeks before the conference. The conference itself was a flip conference, where the publication occurred before the conference itself. It took place online and was a series of live panels that discussed Q&A with the authors of the videos published online. The full papers were published later in the Proceedings (Lahlou et al., 2021).

It must be very clear, and we could verify this in the setting up of the three subsequent netboards cited above, that a human team is indispensable to manage a CKP. The netboard itself, an IT instrument, is necessary, but in the beginning a minimal team of two or three people in charge of the human management, and one or two of adapting the IT infrastructure, is indispensable.

After a few months, a permanent secretariat, an IT hotline, and some strategic management is enough. But the initial phase of bootstrapping the CKP requires intense relational, political and technical work, until a critical mass of participants and resources make the instrument enough valuable for users to attract new participants and keep the current ones contributing. At that stage, the other recommendations of (Wenger et al., 2002), and especially regarding the animation of the community with regular events, become relevant, and these do not require massive investments, but rather a minimal amount of dedicated human resource.

Out of the three other netboards we set up in 2022-24, one CKP died precisely because of the insufficiency of such a permanent secretariat; and we observed the same type of issue on initiatives designed to sustain networks and thematic communities. While the funding is often present to launch such projects, it turns out that the cost of animating the system and having the manpower to do it is systematically underestimated, especially since the secretariat budget lines need to be permanent rather than linked to a transient project. It is an important lesson, but many funding bodies and sponsors seem unable to prioritize it.

5.2. Netboards as installations

Installations are multi-layered devices that scaffold and guide users into following a predictable path (Lahlou, 2017). As an installation, to enable its users get a satisfying experience, a netboard must support their activity by three types of layers: the affordances it offers for action (what can be done technically), the social regulation (what is expected from users) and the embodied competences (what the users know how to do). The first is provided by the digital infrastructure, the second by the animators of the community and the users themselves who guide and control one another, the third is the competences that the users must acquire to fluidly use the system. All these have to be designed and catered for.

The value of the CKP comes from the participation and the size of the community. The positive externalities that bring participants and keep them participating, the social contracts offered by the installation must appear beneficial to participants, and they must indeed be beneficial for them to stay. This means that if we want participants to play their role in the CKP (e.g. provide up-to-date and relevant information, contribute to the collective endeavour) they must get in return a status that provides them access to resources and services. For that, we must understand their motives and provide them with means to fulfil them through the participation to the netboard.

We addressed these three layers as follows.

Affordances:

It is important that there are no technical entry barriers, the use must be possible on all devices (PC, smartphone, various OS, various languages, low bandwidth). We applied the "zeroes" recommendations of the Research on User-Friendly Augmented Environments network (Lahlou, 2009: 119-122):

-

Zero training

-

Zero configuration, Zero impact on user device

-

Zero user maintenance

-

Zero complication

-

Zero payment

-

Immediate benefit for individual end-user

-

High security and privacy

The netboard has no paywall. No account creation is necessary for users, and it is minimal for the referents. The netboard is in full conformity with GDPR. It has a capacity to withstand many simultaneous users reactively. The fact that the threshold for entry is very low makes first experience successful, and later the user can learn how to use the platform in all its power. But even then, the cognitive cost of using the platform is very low.

The netboard affords creating a webpage with a simple series of text boxes, where the owner enters in text the title of the item, a short description or abstract, and the names and coordinates of co-owners (e.g. coauthors, team), and an e-mail address. The other variables (e.g. type of item, location, etc.) are entered by drop-down choice. The interface is multilingual (e.g. 11 languages for WPRN). The process is simple and straightforward, and takes 3 to 6 minutes, including the verification and publication.

While the affordances for humans are made to be simple and straightforward, the netboard has a three-level defence against bots and malicious users. We verify users are human, have a valid web address, and that they do not post offensive content. A further assessment of the quality of the item description is performed by the secretariat, helped by the referents.

Competences:

To be successful in a community, an IT instrument must be used by many, so users benefit from a network effect (e.g. there is no use having a telephone if you are the only one to have it). Our experience shows that the first use must be successful, so the entry barrier must be very low, technically, as seen in the previous section, but also it should not require learning, at least not before there has been at least a first successful use. This means that a minimal use of the netboard should be possible with what are the standard IT competences of a typical target user.

Here, we assume that there is basic internet literacy (knowing how to click on links, fill text boxes, and being familiar with the logic of most comment instruments such as a web browser or a merchant site). That is what is called "design for cognition" (Lahlou, 2011; Lahlou et al., 2002). Then the user may learn in doing, as they use the netboard further.

Furthermore, we added pages addressing a series of Frequently Asked Questions that pertain to the netboard, not just as an IT instrument, but as a tool for the community. These include explanations about validation processes, what is expected from participants, what is the benefit not just for users but for their organisation (as we noticed users may have to provide these explanations to get clearance to publish their items), etc.

Regulation :

The rules of good use and good practice come in three ways. The first, of course, is the limitation of affordance for malpractice or malicious behaviour, and these are done by automatic checks, such as the captcha and address check. What can be entered is also limited by the formats: for example, filling in the descriptive variables (discipline, type, location etc.) is only offered as a closed list. That is "regulation by technology", or "techno-regulation" regulation (van den Berg & Leenes, 2013).

Then, there are also the FAQs and, finally, the secretariat and the referents who monitor content. Bots help the secretariat and referents send messages with predefined content, which they can edit before sending.

The regulation appears to users as messages, either coming directly from referents, or through bots. The bots have their own name and signature, which explains what they are, so that there are no confusions with humans, while still maintaining a minimal level or urbanity, with what we hope is a friendly tone.

For example:

Object: Your project ["ZZZ"] is published on WPRN.

"Dear [X],

Thank you for confirming your address! Your project "ZZZ" is now published and live on WPRN. Here is its public page url: https://wprn.org/item/NNNNNN.

You can edit or delete it using this encrypted link: [link]

Please keep this link for future editions, you will need it to edit or delete your project.

You may be contacted by a WPRN referent in the coming days with a request to edit or update some of your project content. Once validated, your project will be marked as verified by the community.

Feel free to register any other projects related to the societal and human impacts of the pandemic, to circulate the information about WPRN, and to get in contact with other project managers!

Thank you again for contributing to WPRN, a commons for research.

Filipeda, FIrst LInk for Publication and EDit or delete Affordance confirmation bot, on behalf of the World Pandemic Research Network

Sent by WPRN. Click here to edit or delete your project if you don't want to receive any more emails from us on this email address."

Figure 9: Example of a bot message confirming the creation of an item page to its owner.

Interestingly, we encountered, over the 4+ years of operation of these netboards, no instance of hacking, and no attempts for malicious behaviour, at least none that passed the automatic control barriers. The only attempts of malpractice were users pushing a bit too far the publicity for their items, and in some cases the attempt to pass the same items under various guises with several pages (typically, the same research sliced in small papers).

6. Conclusion

Netboards are IT portals to facilitate the creation, management, and promotion of Communities of Knowledge and Practice (CKPs). Combining website, directory, database, search engine, content management system and message board functionalities, a netboard provides the affordances to support the dynamic exchange of knowledge and practice among community members. It enables finding who does what, getting in touch with them directly, and being signalled joiners to the CKP. It also enables signalling one's activities and interests to others and being contacted. The netboard has two main facets: creating item pages and browsing them.

In this paper presenting the concept of CKPs and the challenges and potential linked to their creation and management, we described netboards and how they support CKPs. We also discussed some lessons learned in the creation and management of four netboards (WPRN, The Socioscope, GovernU, IPSP).

The netboard provides functions necessary to participate into, and benefit from, a CKP. It must therefore support, foster and sustain both an activity of information management (creation, display, publish, search, find, update...) and an activity of community management (labelling of persons, organizations and other relevant social entities, and fostering communication from, to and between them).

Furthermore, the netboard enables managing the community, by providing a "back-office" where the animators of the community and a secretariat can extract information, comment and moderate the contents, get in touch with the participants, organise events, broadcast content, etc.

Combining these functions in one single portal (one-stop-shop) facilitates the work of the members of the CKP, the participations of newcomers, interactions with the larger society (e.g. users, policy makers, funders etc.) It is also a tool for the self-management of the CKP.

Experience shows that while good design and a good IT infrastructure are essential, they are not enough. Rather, these elements are just part of what a good CKP should be. Coordination by a secretariat (more intensive at the beginning but still necessary throughout the life of the community), active leadership and animation, as well as the engagement and support of key stakeholders are essential as well.

Another service we identified as what an ideal CKP could provide is data interoperability. Acting as a data source, it enables participants to leverage their effort of participating in the CKP by seamlessly disseminating their input. As such we plan to make netboards harvestable 4 in addition to the already open and available graphQL API endpoint. Another way we plan to achieve data interoperability is to produce outputs structured after goal-oriented tasks, thus offering more traction to the participants in their daily tasks based on the already available data. Finally, we will also import data from existing standard third-party data sources (ORCID, ISNI, ROR...) to assist even more the item creation process.

Therefore, netboards shouldn't be taken as mere repositories of information, but rather as a support for community interactions and for the building of relevant networks. In this sense, actively designing, promoting, and planning for affordances but also for competences and regulation is essential.

- A social contract between parties is one where parties gain status in exchange for playing their role. A role is the set of behaviours others can legitimately expect from that party; a status is the set of behaviours one can legitimately expect from others. (Lahlou, 2024: 104-6)↩

- Zhang, X. (2020).Faire face au coronavirus en chine : réponses et défis. Conference, IEA de Paris, 11 mars 2020. https://doi.org/10.60527/mdd2-cw96.↩

- See https://wprn.org/conference/↩

- See OAI-PMH (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_Archives_Initiative_Protocol_for_Metadata_Harvesting), as well as the CERIF European standard or Vivo.↩