Introduction

In the heart of Bogotá, where economic activity thrives in the shadow of the city's mountainous backdrop, one of its main vessels is soon to be collapsed. Avenidas Caracas and Séptima represent the epicenter of commuting activity in eastern Bogotá; while the first is in process of hosting the first heavy rail metro line for the city, the latter struggles in providing better infrastructure, as it is a political challenge that seems insurmountable.

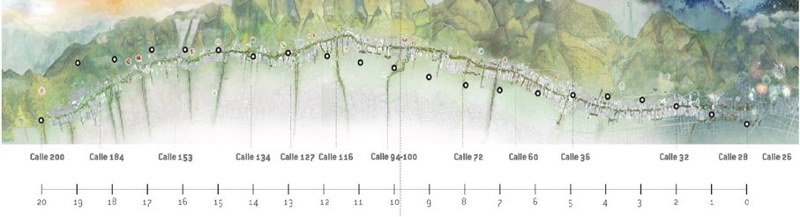

Fig 1. Map of Avenida Séptima in Bogotá, Colombia

The urgent need for solutions to accommodate the current and future demand in this vital area of the city became evident. However, due to its rich historical heritage, narrow sidewalks, and limited lanes, transforming Carrera Séptima into an efficient urban transit corridor presents a formidable challenge. Over the past two decades, the city has seen multiple administrations propose ambitious projects for this corridor, only to face relentless opposition from politicians, high-income residents, heritage preservationists, and environmental advocates, among others. These opposition efforts have successfully stalled numerous projects, obstructing much-needed urban renewal.

One of the most contentious proposals was brought forth by former Mayor Enrique Peñalosa in 2019, which aimed to expand the existing Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network, known as TransMilenio, in a manner that faced severe resistance from a coalition of concerned citizens, local politicians, community-based organizations, and environmentalists. Their efforts, often fueled by legal action, resulted in a judicial battle that completely blocked the project.

As a response to these new ways of interacting with high-scale urban projects Claudia López administration (2020 - 2023) introduced a new approach to the Séptima Corridor project, the Green Corridor (CV7), which was conceived to engage the community in a more comprehensive dialogue, prioritize environmental sustainability, and (try to) foster consensus.

This paper delves into the intricacies of this urban governance and transportation challenge, exploring the conflict that has consistently arisen in the Séptima Corridor. It delves into the literature that studied and dissected some of these conflicts, recognizing them as class-based tension, the result of a lack of openness in participation, and low governmental capacity to respond to legal challenges. It particularly examines the strategies employed by the City of Bogotá -aware of these conflicts- to mitigate the risk of judicial opposition in the development of the Green Corridor.

While the outcome of the Green Corridor project remains uncertain at the time of this paper's publication, the case study serves as a testament to the deliberate and comprehensive approach employed by the City of Bogotá. It underlines the importance of stakeholder engagement, effective communication, and direct negotiations as key tools to mitigate opposition and foster consensus in highly contested urban projects. It also states that this open approach allows new technical and narrative solutions to emerge in project development, and recognizes the combination of these elements as a way to gain leverage and better positioning to overcome the limitations of the previous project.

In an era where urban development projects face increasing scrutiny and opposition, the Bogotá case study provides valuable insights into the complexities of governance, community engagement, and the delicate balance between public interest and stakeholder demands. Ultimately, the winner-takes-all dynamic that often characterizes these projects is challenging, but the city's commitment to building a compelling narrative and creating a more inclusive vision for urban development reflects a promising step toward a more collaborative and productive future.

Global structure

This paper is organized as follows: The first part contains a brief context and discussion around the Séptima Corridor in Bogotá to situate the actions to be analyzed in the context of urban governance, transportation, and socio-legal studies. Then, it will briefly describe the 2016-2019 attempt of pursuing a project in the Corridor (TransMilenio Séptima or TM7) and the network of opposition created around it. Referencing the new approach suggested by City Government (the Green Corridor or CV7) this paper will claim how there is a different design and engagement strategy intentionally conceived to mitigate opposition and innovate in urban design and transportation planning. To bridge this argument the core section of this paper will outline three different challenges identified by the literature in the Séptima (and Bogotá) context and will reference how the Green Corridor approach was intentionally different. These challenges are class-based visions of urban projects, lack of openness in participation, and governmental capacity to articulate and process a different design and judicial strategy. For these three elements the document will provide references and particular solutions achieved or suggested by the administration. Finally the paper will reflect on how these approaches can mitigate some judicial activism (not all) and shape new ways of envisioning urban projects in the city and the region.

Context

Bogotá (Colombia) concentrates most of its economic activity in the eastern border of the city, adjacent to its mountain chain. Because of this, the 100 block wide area between the mountains and Avenida Caracas (colloquially referred as the “expanded downtown”) is the most popular commuting destination in the city carrying half of its total daily trips: 6.5 million (DNP 2017). Nonetheless, the only mass transit service close to this area is the Avenida Caracas TransMilenio, the first BRT corridor of the city inaugurated in the early 2000s, which -by now- is completely out of capacity as it was projected to operate at a maximum load of 35,000 passengers per hour per direction and it is carrying 53,000 and up (DNP, 2017).

With Caracas incapable of supporting all of the trips fed by the BRT network of the city, the eastern border claims for deep solutions that are capable of absorbing current and future demand. Because of the presence of most governmental institutions, the financial

clusters, and elite shopping districts, it is plausible that this portion of the city will continue to be the major trip generator in Bogotá. Throughout the entire “expanded downtown” Carrera Séptima is a few blocks from Avenida Caracas. Although it is the perfect complement for the City’s mobility necessities, it is a challenge for every Mayor in office over the last 20 years to propose and build a project. High income neighbors, public heritage assets, historic parks, and buildings integrate this Avenue in the heart of the city. Its complexity, narrow sidewalks and limited lanes imply that finding the best practical solution to urban transit is very complex.

In recent times, the last five governments of Bogotá have invested millions of dollars in proposals that could not transcend to construction for many different reasons. Every single proposal to do projects with this road has generated controversy, commotion and citizen and neighborhood resistance. The proposal of former Mayor Enrique Peñalosa in 2019 was the one that went the furthest— only a few days from being awarded a construction contract—and the one that had the most citizens organizing against it. His administration proposed a “classic” expansion of the BRT network that he has historically defended for the city (TransMilenio)2.

As referenced by Montero et al. (2023) this was a highly contentious project that generated many different sources of opposition: organized citizens, councilmen, national politicians, community-based organizations and many others. Because of different political and participatory deficit, the project led to judicial actions, mainly the following:

- Community organized against the city of Bogotá claiming collective rights, especially environmental and participatory rights3.

- High-Income development Altos de la Cabrera, claiming affectations to their private property4

- Senator Rodrigo Lara Restrepo against the City of Bogotá for lack of harmonization between planning instruments, environmental claims, and others5

- Environmentalists and Patrimonialists against the project claiming irreparable damages to the city’s patrimonial trees and buildings.6

This challenging panorama faced by the city implied a massive opposition from many different sources, stakeholders and interests. Although they represented different segments of society -including political views- they all came together around the objective of blocking the project.

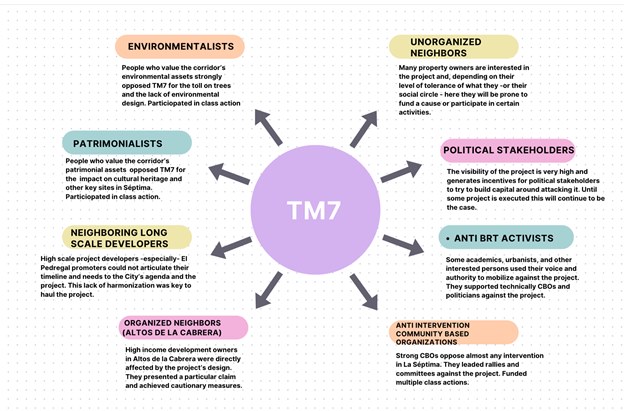

Fig 2. TransMilenio 7 Opposition Map

Table 1. TransMilenio 7 Opposition Map

Sotomayor et al. (2022) document this mobilization of urban and legal expertise against governmental projects as a confluence of different factors. Most interesting to this study are the following: i.) As a way to prompt class-based visions of how the city should be; ii.) As an alternative to more open and engaging participatory processes; iii.) As an expedite way -because of City government’s slow response rate- to paralyze projects until a new electoral cycle comes along.

The Green Corridor (CV7)

On January 1, 2020 Claudia López started her 4-year term as Mayor of Bogotá. As a part of the campaign she insisted on the necessity of rethinking this project and analyzing different alternatives to make it better than a classic BRT. With Transmilenio Séptima paralyzed in judicial courts, her administration proposed a different approach: not only baseing decision-making on classic demand and supply indicators, but also including social dialogue and the fight against climate change as structuring elements of public engagement.

After a broad public consultation process on November 23, 2020 she presented the city’s new approach to la Séptima. A Green Corridor, not only as a zero emissions public transit solution but a design interaction between green mobility, public space, and landscaping; also as an instrument for social dialogue, prioritization and the search for consensus. The project is a dialogue opportunity to discuss equity in road space and to reflect upon the value of quality public space, naturalization and the use of non-polluting alternative modes as the future that the city requires.

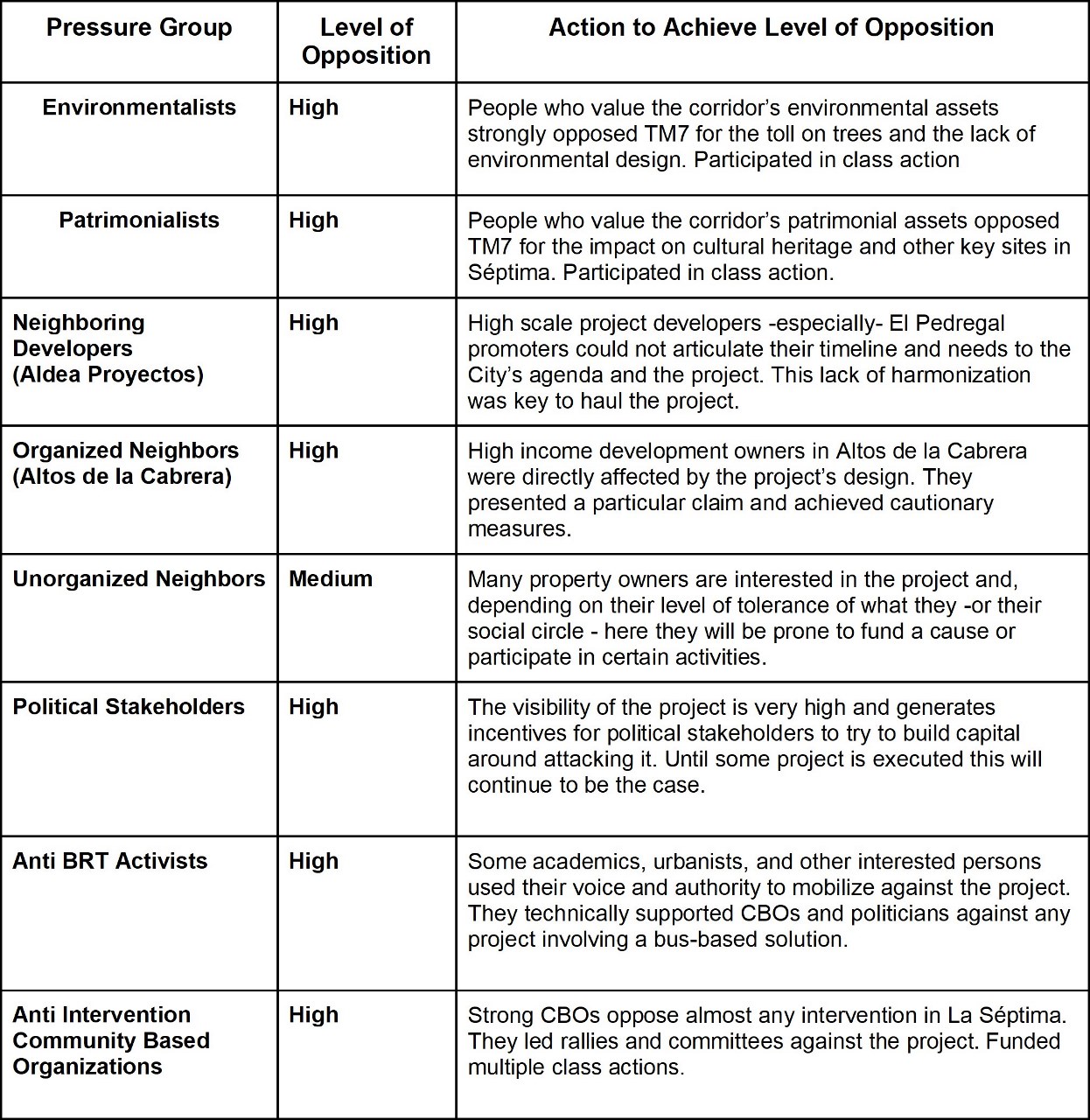

Fig 2. TM7 v CV7 Comparative Design (CRA 7 x Calle 60)

Source: IDU Bogotá (2022)

Most of the diagnostics and conclusions outlined by Montero et al. (2023), were (at least intuitively) acknowledged by the City of Bogotá in the structuring of a new plan to deliver a project in Carrera Séptima. Nonetheless, after a multivariate alternative analysis led by Secretaría de Movilidad in 20217, best public transport solution for the Corridor was still bus based. Because of this, the City anticipated that certain discussions regarding TM7 could come back and some stakeholders will re-engage in discussion.

This paper will present some of the key actions designed by the City of Bogotá in its purpose to anticipate -and win- a judicial battle that could allow an intervention in this corridor. For three of the main factors analyzed by Montero et al., this document will briefly review where they come from and how they were interpreted by city officials (the author being the Project Manager of the Green Corridor) to anticipate a new judicial discussion with better outcome chances for the city.

Problem 1.Class-based vision of urban narratives

Sotomayor, et al. (2022) studied how judicialization of different conflicts in Colombia -particularly after the 1991 Constitution- has increased dramatically and achieved new controls to the administrative power. They also document, however, how this openness has particularly benefited segments of society with more resources to access better law practitioners, influential politicians, mass media and many other sources of power. This tendency, denominated by the authors as “middle and upper class citizens”, have organized before to contest urban projects through different actions successfully (political action, communication, legal actions, etc) and sometimes in detriment of public interest.

Janette Sadik-Khan (2019) reflects on how this approach is a challenge for city governments to overcome effectively.

“Jacobs’s model of grassroots resistance has been co-opted into a perverse politics of rejecting new ideas -and celebrating each defeated project as a victory, even if that victory is status quo (...) Speaking at public hearings, local residents and business owners invoke Jacobs-like language as a smokescreen to fight Jacobs-like projects. They oppose plans for walkable neighborhoods and bike lanes, claiming that they might congest traffic, make streets less safe and pollute the environment or erode property values” (Sadik-Khan, Streetfight, 19)

Acknowledging the necessity of bringing public transit with certain characteristics (interoperable, high commercial velocity, zero emissions, etc) city government realized that the most viable solution that could achieve the operative parameters of the corridor will be bus-based. Most of the stakeholders representing the middle and upper class segment that have historically opposed an intervention in Séptima were very vocal about avoiding an expansion of the BRT network, and/or were particularly interested in maintaining the status quo.

In addition to their resistance to the TransMilenio model in the city “they also oppose infrastructure that may undermine the city’s architectural heritage and ecological structures, and appeal to active mobility, walkability, green corridors, and comprehensive urban design” (Sotomayor et al., 2022). Anticipating this discussion the project concealed two different things when building a narrative: investing time and city-wide resources in rethinking the infrastructure design to be lighter, cleaner, and less invasive, and integrating the project to other aspirational values that these same constituents could resonate to, such as walkability, landscaping, biking, and others.

The latter strategy was required to start atomizing opposition into their real and particular interests. Aware that there were multiple and diverse motivations to oppose an intervention in Séptima, trying to build coalitions around particular aspects that were demonstratively better than TM7 (environmental design, heavy infrastructure implantation, disaffecting relevant patrimonial buildings, and fixing zoning and normative challenges) would isolate the anti-project group and reduce incentives on opposition on many others. Bogotá’s approach integrated some of the visions that motivated organized opposition into the project narrative to build a more just approach to urban design.

This approach, as suggested by Centner (2014), allows for a more inclusive narrative:

“Successful strategies to bolster the right to the city for all will need to push these visions of the right kind of city, to reconcile themselves with the fact that cities are always shared, collective achievements that can only thrive when space- literally - is made for everyone, including those who are on the "wrong" side of distinction.”

Pressure groups heavily invested and organized against TM7 were identified and engaged directly via workshops, events, academic discussions, etc. depending on their core interest. Environmental, patrimonial and some community-based groups acknowledged the design intent to be more comprehensive.

For example, as the project was intentionally heavy on landscaping throughout the entire engagement period, many recognized environmental leaders and activists were involved directly in public discussions and city-led events regarding the necessity of including nature-based solutions into infrastructure development. Shortly after the conceptual design of the project was released -in which it was clear the solution will be bus-based and some discomfort was initiated- the three architecture organizations publicly backed the initiative:

“We consider that the conceptual design disclosed by the current administration of Bogotá responds to the fact that much of it is tenable for a long time, that it is conceived as an act of love and responsibility for the city and its natural basis.

We understand that a process of creation as it is in progress responds to the desire of the individual to live, and enjoy the landscape. A balanced framework that reconciles diverse visions of past and future administrations and allows it to fluidly articulate the activities of civil society.(Rojas, Fajardo, Martínez, 2021)”

Gathering input, including concepts experts value into the design and highlighting their involvement, making it clear and demonstrable how their suggestions were included in the final design of the project, was critical through this engagement process.

Problem 2. Openness in participation

In high scale/ long-term projects it is easy for communities to understand and even calculate costs but benefits are diffuse (Foster & Warren, 2021), making public engagement and communication very challenging. Although the TM7 participatory process included city efforts to achieve engagement and participation this was not perceived nor recognized by constituents. As documented by Montero et al. in 2023 many communities referred to this process as a “top-down” and “socializing” process instead of a participatory opportunity that enriches the final design decisions. There was a strong feeling in participants that meetings were held as a formality to validate decisions previously made in technical instances:

According to a participant, when residents or groups raised an issue concerning a project, the professionals responsible for the projects would respond with what, to citizen groups, sounded like: “this has already been decided, this is all technically based, here we are, the owners of knowledge” (pers. comm., 04/29/2020). Legal activism thus became the counterpoint to Peñalosa’s brand of top-down technocratic planning.

Public consultation processes are challenging as some people expect to expand their incidence to the realm of co-administration. In order to take distance from top-down and “socializing” without misleading expectations to participants, the City structured a strategy with different levels of engagement: from open access to information to direct incidence in some decision-making. These alternatives included direct co-design workshops structured by neighborhoods, massive newsletters and communications, in-site hauls, and a participatory design campaign using the Streetmix platform, among others8.

Output of this initial process was used for different purposes, mainly two: legitimacy and achieving a broader sense of openness in participation, and, more importantly, demonstrate that potentially contentious design decisions (such as a limitation on space devoted to private cars) were in line with the aspirations of citizens participating in the process. All of these efforts were documented and made public through official websites and instruments and included in the narrative of the different stages of the process.

Some of the key insights of the initial phase of engagement include the following -as reported by the Instituto Distrital de Participación Comunal IDPAC:

"The participatory process involved informative, consultative, deliberative, and educational tools. Approximately 1.5 million people were reached through the strategy, with 34,180 interactions on social media and mass media. According to a survey, 4 out of 10 people had prior information about the green corridor, with the highest proportion (55%) in the 40 to 100 segment.

There were 36 deliberation spaces with 2,239 participants. Additionally, three educational forums via Facebook Live engaged 395 in the room and reached an additional 115,000. Various citizen consultation actions were implemented, including Bogotá Abierta platform, Séptima Verde website, WhatsApp, street consultations, and StreetMix, resulting in 49,519 responses and 56,288 proposals when compiled. Furthermore, a survey was conducted among 1,521 households with individuals over 18 years, with a margin of error of 2.9%.

Despite the ongoing public debate on mass transit, the public did not prioritize it. Instead, there was more interest in walking, biking, and skateboarding, with occasional interest in electric buses or trams when discussing mass transit."9

A particular example of effectiveness was the use of an open source software “Streetmix” as a part of the participatory process in 2020 due to a partnership between the city and the New Urban Mobility Alliance “NUMO”. As recalled by Carlos Pardo

“participants could easily create and submit their own proposals to indicate their vision for 15 key locations along the avenue, which were measured to scale and recreated online. (...) Over those two weeks in October, nearly 7,000 proposals from 6,000 users flooded in, 91% of which met all requirements. Streetmix saves each proposal in code, which allowed NUMO to create a precise breakdown of what participants wanted to see on the redesigned Séptima – from public transit to cycling and walking. This analysis provided the city with actionable ideas from those who actually use Séptima (2021).

Fig 3. Real Streetmix Interactions During MiSéptima Campaign

Pardo documented some of the findings of the usage of this open source platform as an innovative participatory strategy as follows:

“Results showed that participants favored active and shared modes, creating streets that in aggregate allocated 56% more space to bicycles and skateboards and 74% more space to public transit than the status quo, while reducing space for private automobiles by 19%. Overall, proposals reduced emissions by an average of 6% for the avenue and up to 26% in one segment. Participants preferred increasing capacity through prioritizing active modes and public transit. Finally, 248 proposals integrated autonomous vehicles, indicating Bogotá’s openness to change and innovation on this front.” (Pardo, 2021).

In a broader sense, the objective was to highlight other elements of the discussion around infrastructure development (not only modal pick) and to democratize and celebrate other elements of these projects that city government could actually deliver (such as an increase in quality public space, green areas, safe infrastructure for bikers and pedestrians, etc).

With a strong documented case of quantitative and qualitative participation, intense communication strategies, and presence in academic and social spaces the administration wanted to effectively build a narrative that could resonate in an intent towards building a more holistic project as per request of the citizens involved.

Problem 3: City’s Administrative and Legal capacity of response for class actions

Coming back to the actors discussed beforehand, there is an inclination in the Colombian legal and social context for “middle and upper classes” to use legal actions to legitimize their view of the city (Sotomayor et al, 2022). Many of these actors found legal actions (such as acciones populares or tutelas) -summed up with rallying, Public Relations strategies, and opportunistic politicians- as the best strategy to achieve short-term blockage of these projects.

Most of these actions were successful when they found a legal detail that was not clearly resolved by the administration more than a particular right to be safeguarded:

Finally, for many of the citizens and politicians we interviewed, resorting to the judicial process implied learning what makes an infrastructure project vulnerable from a legal point of view. That led to the fact that many times the process became a search for legal details to interrupt a project rather than a deep deliberation on its merits or limitations (Montero et al., 2023).

The overall approach to this challenge -in which particular governance issues, a sensible lack of articulation between public institutions, or lack of capacity to plan a better defense put at risk the final delivery of the project- was to resolve independently each critical issue related to the project and included into the comprehensive engagement strategy.

The most notorious cases were Altos de la Cabrera and Plan Parcial El Pedregal. The first was a legal action filed by high-end apartment owners alleging that the construction could cause irreparable harm to their private property and other collective rights such as a clean environment. Although once the City demonstrated the particular design will not be executed and the action was filed, owners emphasized that without their validation of the final design, they will pursue a new legal action. Throughout the detailed design phase Altos de la Cabrera owners were invited to workshops and the Instituto de Desarrollo Urbano (IDU) would explain design improvements after listening to their particular concerns.

For El Pedregal -a large scale development or Plan Parcial-, a judge determined that TM7 was not correctly harmonized in design, thus it would be illegal to execute the project. A contentious discussion with the developer -which included a $142.990.416 USD lawsuit claiming bankruptcy for lack of coordination with city government10- was deactivated during López administration through intense and careful interagency work. Finally on July 18, 2023 the Secretary of Planning and the Mayor’s Office announced a new decree that allowed the completion of Plan Parcial Pedregal including a design solution that was explicitly harmonized with the Green Corridor Project.

Focusing institutional capacity -and articulate critical components such as utility design, transit, infrastructure, public finance, and zoning- to articulate a shared solution that mitigates risk of future litigation was the main objective.

Discussion

Although at the time of publication of this paper it is uncertain if this project will be finally built, it is safe to argue that the Bogotá government was intentional in articulating a new design process capable of mitigating judiciary risk where possible. At least in this case, which has an important background and documentation, the final design of the Green Corridor was a result of a major intent of openness, stakeholder segmentation, and direct negotiation. All of these techniques allowed the city to be more flexible on different design principles previously untouched (road design parameters, station design, landscaping, public space design, transit-oriented development principles, among many others) and produce a functional solution highly different from Bogotá’s traditional infrastructure.

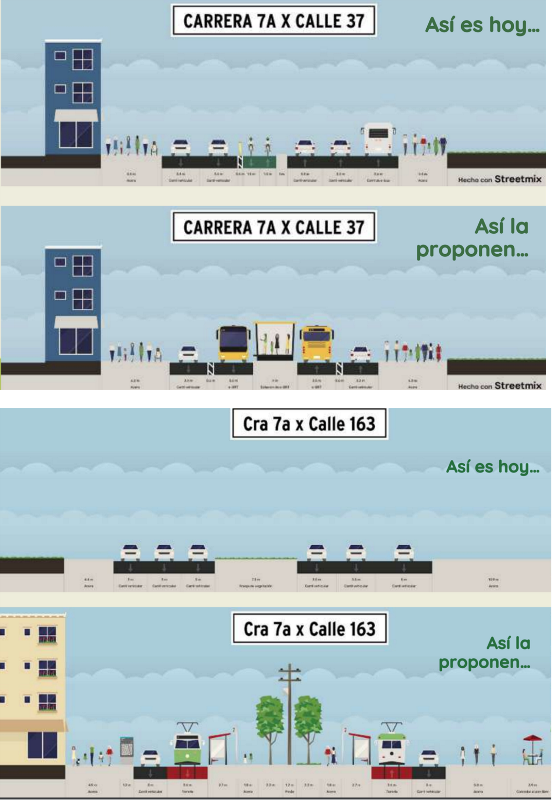

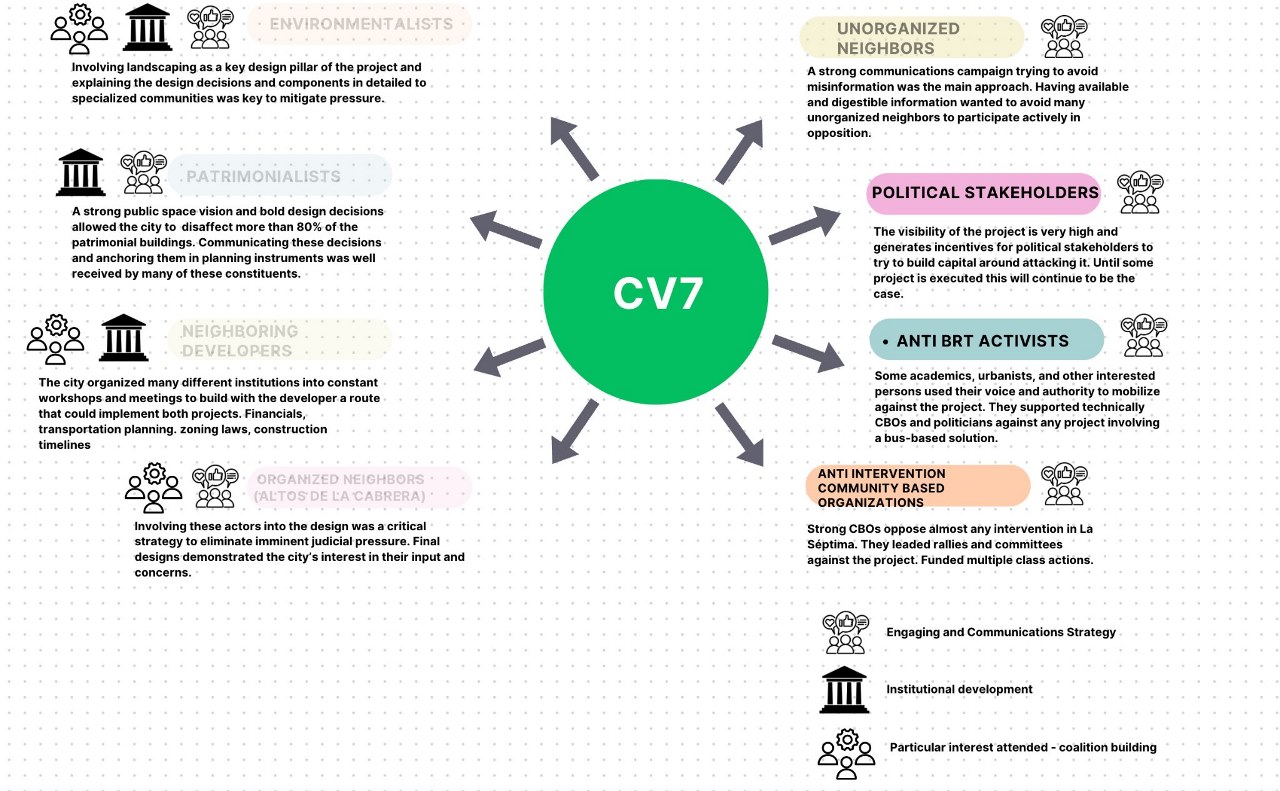

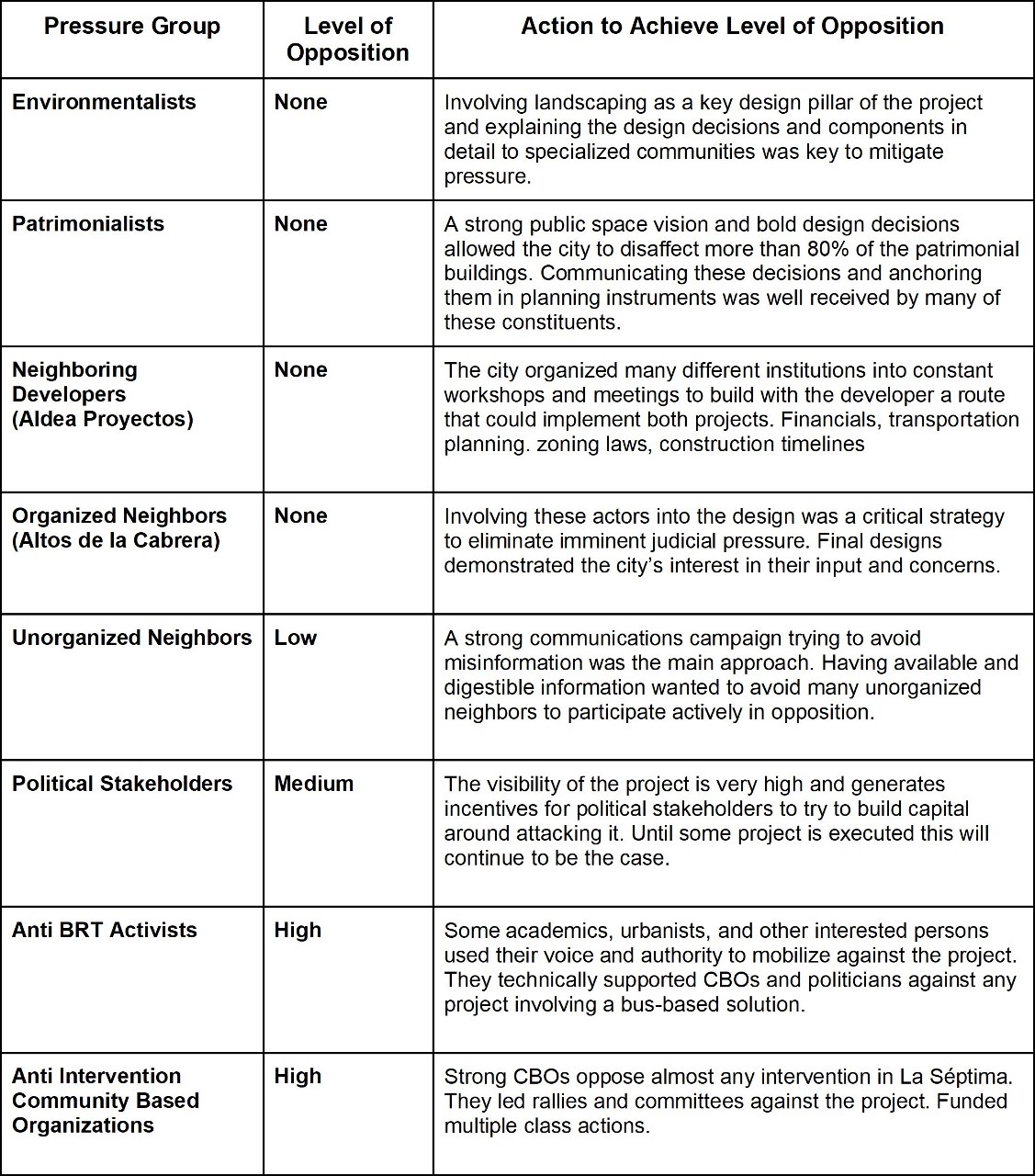

With special attention to attend particular stakeholders, interests and through a more comprehensive governance strategy pressure groups that were strongly vocal and organized in the TM7 process lacked incentives to continue: environmentalists, patrimonialists, developers and former plaintiffs with very specific interests were treated from a more open and inclusive approach which was effective in mitigating their interest in continue engaging in judicial action. Political stakeholders, anti BRT Activists and anti-intervention CBOs continue to organize against the project in very similar ways as they did against TM711, which demonstrates still mobilizing legal expertise to promote certain visions and agendas (and particularly the blockage of city projects to achieve certain vision of the city) will continue to be present in highly contested projects.

Fig 4. Green Corridor 7 Opposition Map

Table 2. Green Corridor Opposition Mapping

The takeaway on Bogotá’s approach to contain judicial activism against this project can be summarized as follows: i.) It is useful (and necessary) to build better engagement strategies and an institutional response capable of avoiding -or even atomizing- different interests surrounding high-impact projects; and ii.) Projects should build -and sustain through their entire life- a relatable narrative that can sustain the atomization of stakeholders. It is critical to build -and document- a stronger case around more typical collective rights to be contested (environment, public participation, planning principles, etc).

Current urban governance challenges require city governments to be more audacious, and inclusive in their project design. Although technical restrictions and broader visions are fundamental for high-scale interventions, political sensibility and diagnostics can open space for innovation and further effectiveness. Achieving a good mixture between the technical constraints and stronger narratives can help governments find convergence with relevant stakeholders minimizing implementation risks.

Conclusion

This Bogotá case illustrates the expansion of checks and balances to executive action from citizens and judicial authorities. Political processes in Colombia, and more specifically in Bogotá, are challenging and diminish any administration capacity to pursue a broader consensus on high scale urban projects. Because of this it is expected to experience conflict and contention in every structuring process.

The winner-takes-all structuring of these projects (either the city builds what it considers best for public interest or some stakeholders achieve to stop it and maintain status quo) is costly and very high-risk. Stakeholder management, public engagement, better communications, and direct negotiations can mitigate some pressure (and sometimes it can be enough to produce a better outcome) but there is a deeper political challenge yet to be explored and understood.

Bibliography

Acción popular 25000234100020180068300 (2018-683) (Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Sección Primera – Subsección B Magistrado Ponente Oscar Armando Dimaté Cárdenas 2018).

Acción popular 11001334306020190001700 (2019-017) (Juzgado 60 Administrativo del circuito – Sección Tercera 2019).

Acción popular 11001334204920190012200 (2019-122) (Juzgado 49 Administrativo de oralidad de Bogotá D.C. 2019).

Acción popular 11001333502320190009500 (2019-095) (Juzgado 23 Administrativo del circuito – Sección Segunda 2019).

Acción Popular 11001333603520230027300 (JUZGADO TREINTA Y CINCO (35) ADMINISTRATIVO DEL CIRCUITO JUDICIAL DE BOGOTÁ - SECCIÓN TERCERA - 2023).

Alcaldía de Bogotá. YouTube. (2020). Conoce el Diseño Conceptual del Corredor Verde de la Carrera Séptima. YouTube. Retrieved September 28, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E1tu_xMLYsE&ab_channel=Alcald%C3%ADadeBogot%C3%A1.

Centner, R. (2014, May 25). Distinguishing the right kind of city: Contentious urban middle classes in Argentina, Brazil and Turkey. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/6130044/Distinguishing_the_right_kind_of_city_Contentious_urban_middle_classes_in_Argentina_Brazil_and_Turkey

CONSEJO ECONÓMICO DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA Y SOCIAL , C. N. D. P. (2017). CONPES 3882 de 2017. Apoyo del Gobierno Nacional a la Política de Movilidad de la Región Capital Bogotá-Cundinamarca y Declaratoria de Importancia Estratégica del Proyecto Sistema Integrado de Transporte Masivo - Soacha Fases II y III. Departamento Nacional de Planeación. https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Conpes/Econ%C3%B3micos/3882.pdf

Foster, D., & Warren, J. (2021). The nimby problem. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 34(1), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/09516298211044852

Instituto Distrital de la Participacion y Accion Comunal - IDPAC. (2021, November 30). INFORME DE LAS ACTIVIDADES DE LA RUTA DE LA PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA INCIDENTE EN LA PRIMERA FASE DE LA ETAPA DE CO- CREACIÓN DEL PROYECTO CORREDOR VERDE DE LA CARRERA SÉPTIMA. https://www.participacionbogota.gov.co/sites/default/files/2020-12/informe_final_ruta_participacion_CV7_2-12-20.pdf

Mojica, C. (2011, May 10). Transmilenio: The battle over Avenida Séptima. HKS Case Program. https://case.hks.harvard.edu/transmilenio-the-battle-over-avenida-septima/

Montero, S., & Sotomayor, L. (2023, February 11). Judicialización y política urbana: Ciudadanos, Políticos y Jueces en la suspensión de Transmilenio por la séptima en Bogotá. Revista EURE - Revista de Estudios Urbano Regionales. https://www.eure.cl/index.php/eure/article/view/EURE.50.149.05.

Pardo, C. (2021, January 7). How Bogotá is turning 7,000 citizen proposals into a real plan to redesign a major thoroughfare: . TheCityFix. https://thecityfix.com/blog/how-bogota-is-turning-7000-citizen-proposals-into-a-real-plan-to-redesign-a-major-thoroughfare/

Pardo, C. (2020). Streetmix para la Séptima verde. Séptima Verde. https://septimaverde.gov.co/web/content/2553?unique=ebb7c68485184e553933a961b2cfb7d9d682240d

Reparación Directa 25000233600020210006200 (2021-062) (Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Sección Tercera –, Magistrado Ponente Fernando Iregui Camelo 2021).

Rojas, M., Martínez, W., & Fajardo, M. (2021, November 30). Arquitectos y paisajistas de colombia respaldan el corredor verde de la séptima. Bogota.gov.co. https://bogota.gov.co/mi-ciudad/arquitectos-y-paisajistas-respaldan-el-corredor-verde-de-la-septima

Secretaría de Movilidad, & Instituto de Desarrollo Urbano. (2021, March 12). CORREDOR VERDE CARRERA SÉPTIMA: ESTUDIO DE IDEA Y PREFACTIBLIDAD. Septima Verde. https://septimaverde.gov.co/web/content/2664?unique=f5daa219ddadc21db99859750bd8d26b88b4e457&download=true

Sotomayor, Luisa & Montero, Sergio & Angel-Cabo, Natalia. (2022). Mobilizing legal expertise in and against cities: urban planning amidst increased legal action in Bogotá. Urban Geography. 44. 1-23. 10.1080/02723638.2022.2039433.

- As mentioned by Mojica in HKSCase1942.0: A key difference between TransMilenio and other fixed busway systems was the presence of a second lane at stations that permitted buses to overtake one another and made express services possible. This second lane was thought to boost the system’s capacity from 15,000 to more than 40,000 passengers per direction per hour. Avenida Séptima had a 5 km stretch where the right-of-way was too narrow to accommodate the intended provision, in each direction, of one bus lane plus an additional lane for overtaking in the stations, two mixed traffic lanes and a sidewalk. Harvard Kennedy School of Government. (2011) The Battle Over Avenida Séptima, HKS case 1942.0 ↩

- Acción popular 11001334306020190001700 (2019-017) (Juzgado 60 Administrativo del circuito – Sección Tercera 2019). ↩

- Acción popular 11001334204920190012200 (2019-122) (Juzgado 49 Administrativo de oralidad de Bogotá D.C. 2019). ↩

- Acción popular 11001333502320190009500 (2019-095) (Juzgado 23 Administrativo del circuito – Sección Segunda 2019). ↩

- Acción popular 25000234100020180068300 (2018-683) (Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Sección Primera – Subsección B Magistrado Ponente Oscar Armando Dimaté Cárdenas 2018).↩

- Secretaría de Movilidad, & Instituto de Desarrollo Urbano. (2021, March 12). CORREDOR VERDE CARRERA SÉPTIMA: ESTUDIO DE IDEA Y PREFACTIBLIDAD. Septima Verde. https://septimaverde.gov.co/web/content/2664?unique=f5daa219ddadc21db99859750bd8d26b88b4e457&download=true↩

- Documento de participación IDU. (2021) ↩

- Reparación Directa 25000233600020210006200 (2021-062) (Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Sección Tercera –, Magistrado Ponente Fernando Iregui Camelo 2021). ↩

- Acción Popular 11001333603520230027300 (JUZGADO TREINTA Y CINCO (35) ADMINISTRATIVO DEL CIRCUITO JUDICIAL DE BOGOTÁ - SECCIÓN TERCERA - 2023).↩