Figure 1. Structure of the paper: key questions

Source: Alena Ledeneva for Galerie de Buci, Paris. Copyright: Lesha Kostromin.

I. What is informality? What is it the case of?

Let us start with the problem of qualification: what is informality? What is it the case of? The literature on the subject is vast. Google Scholar alone returns 175,000 sources for the term 'informality' with over 10,000 from 2024 alone. The majority of sources explore informality that is visible or tangible: informal settlements, informal economy, informal employment tied with issues of development, poverty, inequality, urban planning, and gender. The multiplicity of discourses on informality is overwhelming, and goes back to the 1960s. The unevenness in coverage of various aspects of informality - some of which are more open for exploration, others remain locked in private spaces and tacit knowledge - can be illustrated by a GenAI image. As depicted in Figure 2, one-legged, biased or stigmatised views of informality are also an issue. In line with the social sciences tradition, most of the sources on informality tend to be single-authored or have only a few co-authors. The perspective of the Global Informality Project (GIP, 2014-2024) is radically different.

First, it draws on collaboration, the "network expertise" of the global community of scholars (currently over 600) in order to demonstrate the diversity of informal behaviour in human societies, thus amounting to their infinite or contextual social and cultural complexity. Given the cross-disciplinary and cross-regional nature of the Global Informality Project, it would be impossible to agree on a definition of informality acceptable to all. We have therefore used 'informality' as an umbrella term for the many phenomena that are too diverse to be captured in a single definition. In this broad, inclusive sense, informality refers to the ways of getting things done to meet human needs. The GIP findings point to the world's open secrets, unwritten rules and hidden practices that elude articulation in official discourse but reveal the 'know-how' of what works for problem-solving as it is known in the vernacular. Each contributor to the project brings an additional perspective to the at least 50 year history of definitions, typologies (see also, for example, the typology of street vendors) and efforts to measure informal behaviour. To paraphrase Nietzsche, informality is probably one of those terms that has a history rather than a definition.

Figure 2. Informality chest of drawers

Source: DeepL generated image. Copyright: Alena Ledeneva.

Second, the project takes a linguistic turn: capturing Wittgenstein's "language games" of participants of informal practices allows us to offer a bottom-up perspective that distinguishes practices from concepts, behaviour from its categorisation in the language of observers. They are as pervasive as the use of the vernacular terms, or language games, associated with gaining an advantage: pulling strings in the UK, red envelopes in China, pantouflage in France,l'argent du carburant given to customs officials in sub-Saharan Africa, duit kopi, or coffee money, paid to traffic policemen in Malaysia. Located in grey areas, taken for granted yet questionable, acceptable among 'us' but reprehensible among 'them', difficult to measure, monitor and integrate into policy, these practices are deeply woven into the fabric of society. Historically, the earliest studies of tricksters or ways to gain competitive advantage can be found in the mythology and folklore of various cultures. While such practices are rather banal, they can also be uncomfortable to discuss and impossible to research. To establish patterns behind the multiplicity of practices we have collected the euphemisms for them in the language of the participants. We have created the first database of 'an informal view of the world' - The Online Encyclopaedia - where the entries appear in their local habitat and are identified in the language of origin. In the published volumes of the Encyclopaedia, however, entries are grouped into clusters to bring together similar practices from around the world, thus highlighting their contextual features while also pointing to the universal patterns of human problem solving.

Third, we question the local nature of informality. Analysing the tensions between specific/universal and local/global features of informality goes much deeper than presuming the state-centric formal/informal dichotomy. The dual nature of informal behaviour - it is always local because it is contextual - is inscribed in specific circumstances, normative constraints and cultures - yet it is also global in the sense that it is a fundamental form of human cooperation, universal to human problem solving. For example, we found little country variation in oppressive contexts: patterns of human interaction within closed organisations such as boarding schools, prisons, armies and psychiatric hospitals tend to be fundamentally similar in democratic and autocratic societies. Informality is thus a shortcut from the local to the global, from the specific to the universal, from trust-based tactics to strategies for dealing with the complexity of the contemporary world, and vice versa, and in constant oscillation between the two. In other words, the project disentangles informality from the area studies. Rather than reaffirming regional divisions, we open doors for practices from around the world and bring them together, regardless of their geographic origins. The third volume gathers informal practices from fairly universal stages of human biography, while also highlighting the range of problems and the diversity of solutions that exist around the world.

Fourth, we qualify the role of the state, which tends to be a key force in reducing informality. Research shows that the state can also be seen as complicit in causing informal problem solving. Furthermore, the centrality of the state and its formal institutions is typical of Western perspectives, while the focus on informality from the bottom-up perspective (the art of not seeing like a state) restores a historical logic whereby informality precedes formality. Also Western is the assumption that informality is synonymous with poverty and underdevelopment, whereas our database suggests that it is also associated with various forms of wealth and power.

Fifth, we investigate the patterns of informality. Informal practices as such are diffuse, amorphous and ubiquitous. They are often invisible, resist articulation and elude measurement. They are contextual and banal, but also complex and central to human cooperation. Yet the greatest challenge for working out 'what informality is the case of' is the ambivalence of informal practices: they are both a solution and a problem. Like with a quantum particle, we find two modalities at once: informal practices are one thing for participants and another for observers. For example, patron-client relationships can be seen as a means of levelling the playing field and giving an underdog a chance (see the practices of eating, or *kula*in Tanzania). On the other hand, the same practices can easily lead to chains of illicit exchanges involving votes and other resources (see the practices of raccomandazione in Italy). The use of connections and recommendations involves a fundamentally human reliance on family, friendship, solidarity and reciprocity. At the same time, such ties can be associated with cunning, and disparaged as a way of poor man's making do (l'arte dell'arrangiarsi in Italian or *la débrouille*in French).

Informality is thus rooted in the universal human capacity for creativity and for resolving ambivalence in specific contexts by mastering doublethink, double standards, double deeds and double incentives. Double standards regarding family ties illustrate the problem of contextuality (and positionality) in measurement and interpretation. Western scholars praise family business in the West as a laudable institution, while criticising nepotism arising from family ties in the East. In both cases, the pattern is the use of family ties or personal networks as a shortcut to an outcome parallel to, above or beyond the state provision and control. In line with the ambivalence of the informal ways of getting things done, informality is best understood as a case of a shortcut, a way of navigating both formal and informal constraints on problem solving. It is an alternative route to the one prescribed by the formal rules and roles, but it also plays the informal rules and roles to one's advantage. Shortcuts are fundamentally ambivalent: they solve problems but also create new ones, they are inclusive but also exclusive, they subvert political and economic systems but also support them.

II. So what? The implications of the Global Informality Project research findings

To answer the "so what" question, I offer some insights from the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality that could be integrated into policy-making and training for decision-makers. I start with the need to reassess existing assumptions about informality and skills development to address the challenges and potential of informality for problem-solving.

Informality is both a problem and a solution. 'Neither--nor' or 'both--and' patterns of ambivalence dwell on dichotomies but also aim at circumventing them. For example, normative ambivalence, associated with the double standards embedded in identities, solidarities and the fundamental divide into 'us' and 'them,' makes it possible to turn constraints into opportunities. In his concluding remarks to the first volume, Zygmunt Bauman identifies the implications of the organising forces of modernity and argues that the divisive nature of dichotomies must give way to a cosmopolitan mindset in order to confront tendencies toward radicalisation and fragmentation, driven by divisive identity politics and religious beliefs. It is the potential of ambivalence that can be integrated into such policy thinking.

The key findings presented in Volumes 1 and 2, address the paradoxes of informality and point to the types of ambivalence that tend to escape academic analyses and policymaking discourses alike. Published in 2018 in the FRINGE series by UCL Press, these two volumes explore the grey areas between informality and corruption and implications of the blurred boundaries for anti-corruption policy.

The cross-disciplinary approach taken to identify similarities in differences and differences in similarities of informal practices around the world challenges assumptions about the centrality of formal institutions.Instead, we find that the persistence of informality correlates with the nature of informal networks. Specifically, informal institutions and practices embedded in networks that are "relatively affective" and "relatively closed," are much harder to transform than those enacted by "relatively open" and "relatively instrumental" networks.

The context-sensitive comparisons made possible by the project challenge several reductionist assumptions about informality: its residual status vis-à-vis formality; the primacy of legal over social norms; its association with the periphery rather than the centre; and its equation with underdevelopment, poverty and inequality. As many entries in this encyclopaedia point out, informality is central to local culture and community life in the form of giving and sharing, not necessarily associated with poverty and inequality. The Italian practice caffè sospeso eliminates the identity of the donor of a free cup, left for a local recipient, thus creating a long reciprocity cycle, whereby coffee falls down 'from the clouds', not from the donor's hands. The suggestion is to tackle complexity by complicating models, rather than downplaying complexity to enable quantitative comparative analyses.

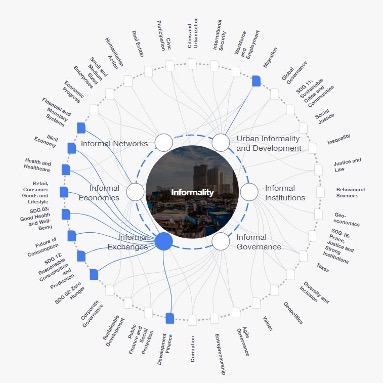

The project has confirmed that the assumption that informality is a measure of development or rather underdevelopment is questionable at best. From a local perspective, informal settlements and economies are common in the global South and are associated with underdevelopment and repressive regimes. It is therefore tempting to think that informal practices can, to some extent, serve as indicators of the effectiveness of formal institutions. However, from a broader perspective, informality is also rooted in universal patterns of behaviour associated with informal networks, informal exchanges, informal governance or informal power (see WEF Informality maps).

Figure 3. Multi-dimensional modelling of informality

Source: UCL-led strategic and contextual intelligence map, enabled by the WEF and Horizon2020-MSCA-ITN MARKETS project (GA 861034).

As can be seen from browsing the interactive AI-enabled strategic maps that link related issues, poverty and development are only a fraction of the issues that correlate with informality. The visibility of informal practices is linked to poverty and development, but not informality per se. The more developed societies are, the less visible (or hidden behind the facades of formal institutions) are their informal underpinnings. It is not that informality does not exist in developed societies, but rather that it does not clash with the formal rules, and the social norms that have evolved in these societies have obscured it. This invisibility stems partly from respect for legal norms - informal practices tend to take place either below or above the radar of the law - and partly from practical norms, or the banality of informality, which allows good citizens to engage in behaviour that they do not necessarily find acceptable upon reflection. Visualising the hidden links with the help of AI-generated strategic contextual maps, designed by the WEF strategic intelligence team to connect problematic areas, helps integrating complexity into decision-making. Taking the less visible aspects into account in policy making is essential for its effectiveness (Figure 3) but measuring and indexing them could be counterproductively simplistic.

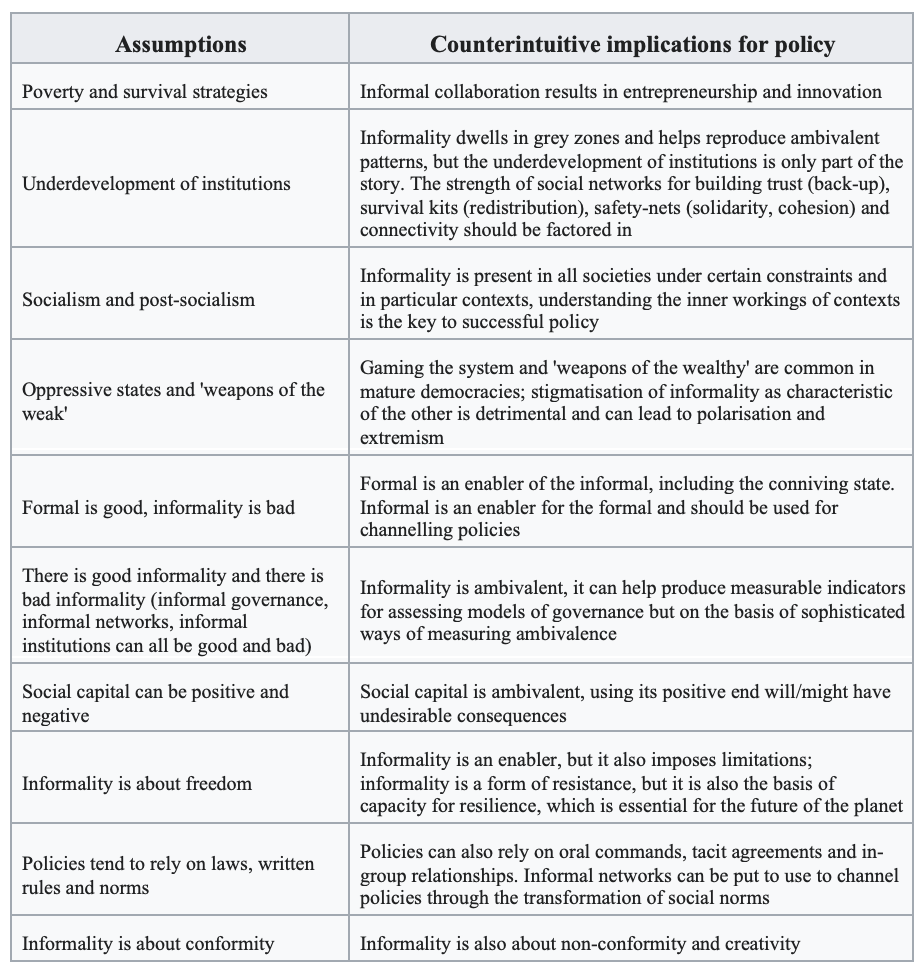

Perspectives on informality that focus on its subversive impact on the development of political or economic regimes, rather than its supportive functions, often lead to the so-called informality crusades and predict its disappearance in transition to more effective formal institutions. While it is tempting to think so, I argue that stigmatisation of informality is counterproductive in policy making and sums up the assumptions that need revision and re-framing (see Table 1).

Table 1. Assumptions about informality vs its transformative potential

Overall, to answer the "so what" question, I argue against the simplistic approaches to informality. Academically, there is a need for informality studies that prioritise problem solving and work across existing disciplinary and area studies divisions. To this end, I articulate the raison d'etre of informality studies in the third volume of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality. Drivers for change that are undermining and/or transforming the previous paradigm of modernity include: facing uncertainty arising from the challenges that both nature and nurture have imposed on upon human societies, as well as the emerging intellectual challenges of transcending Western-centric transitional paradigms and balancing out a-historical, state-centric thinking. For example, the workings of patronal or hybrid systems require an entirely different conceptual framework, as opposed to normative approaches. Bringing together research networks focused on a problem-oriented approach is the best-known way of crossing institutional and national borderlines in the history of informal scientific collaboration.

Reflecting on the expertise, gathered in the three volumes of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, I summarise the skills and offer innovative tools required to develop the field in the introduction to the third volume. Here I focus on the experience of their use in practice.

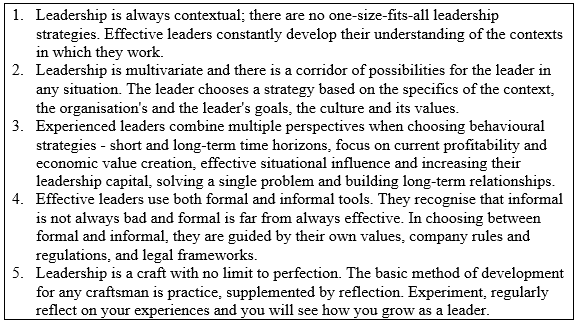

The immersive training for policy makers, aimed at mastering complexity and context sensitivity, dealing with uncertainty and leadership development includes a simulation game --the Informality game - and a case study - the Network leadership case. Training leaders to manage uncertainty is arguably the key survival skill in a post-pandemic world, characterised by individual vulnerability to societal crises. The use of board games has been taken up in educational contexts and training grounds for transnational governance. The Informality game, modelled on the structure of Monopoly, is much more complex, as it does not assume right or wrong answers, stimulates contextual awareness, and highlights the ambivalence of social capital (same networks can have both positive and negative outcomes). Adapted for the global corporate contexts, the Informality Game has been used for leadership development (see summary of the takeaway points in Box 1), while the Networks Leadership case has been used for regional leadership development programmes.

Box 1. Five takeaway points of the Informality Game

III. How would you know if you were wrong?

In short, collaboration is the answer. As Giuseppe Longo, a former fellow of the IEA-Nantes has postulated, competition is much easier, in science, than collaboration: "It may even be based on cheating, on announcing false results, declaring non-existing experimental protocols, on stealing results, organizing networks of reciprocal, yet fake quotations. Collaboration instead is very hard: good scientists are very selective in accepting collaborators and diversity makes the dialogue difficult while producing the most relevant novelties." The Global Informality Project is a case of true collaboration, resulting in an extraordinary collection, described as a "fascinating, indeed unique and enduring collection of descriptions and analyses of informal practices from around the world". Its uniqueness lies in the collaboration of scholars who have brought together practices that have never been seen together before. The unintended consequence of the project is a truly global, cross-disciplinary and cross-regional bibliography on informality around the world - a brilliant outcome in itself. Follow-up introductions, co-authorships, research networks and successful funding bids are also evidence of successful collaboration. Over the decade 2014-24, the editorial team has brought together a variety of perspectives from social science research, journalism, investigative reporting, media and foreign office analysis, anti-corruption activism and governance. Junior editors, trained as doctoral or post-doctoral students, have gone on to successful careers in academia and beyond. Reflecting on the management of the dataset and the collaborative methods of the Global Informality Project, I have distilled the following safeguards to verify the authenticity of our findings:

- Reliance on language games spread in user communities; crowdsourcing as a data collection technique and cross-referencing of entries reduces personal biases of contributors.

- The reliance on research networks (with thanks to Abel Polese, who has been the project's global ambassador over the years and has inspired the spirit of collaboration; Alina Mungiu-Pippidi; Predrag Cvetičanin; Eric Gordy and many others) and the scale of the project have created the critical mass of material that has allowed us to elevate the project from the status of a haphazard accumulation of encyclopaedia entries to a meaningful process of mapping grey zones, blurred boundaries and other forms of social and cultural complexity.

- Dialogue with authors from different parts of the world and different disciplines during the multi-stage editorial process (scroll down to see the data on project progress dates).

- Bottom-up structuring of the published volumes - students were given access to all the contributions and asked to decide 'what each practice was the case of' and which ones belonged together in the same cluster. Different clusters were created in student workshops as well as in collaboration with colleagues (see for example, the INFORM comparative project in nine countries of the Western Balkans, 15 fellows of theMSCA-ITN MARKETS project, funded to train the new generation of informality scholars).

- Cross-examination in light-touch peer review as part of the editorial process, where the editors and reviewers would share their reservations with authors.

- Consulting gurus in the respective fields and inviting authors of conceptual introductions and conclusions to look at the clusters of entries and offer their conceptual framing of the material, as well as giving young scholars a chance to do conceptual work.

- Anonymous reviewers of the published volumes of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality and their feedback helped to perfect the structure of all three volumes and to refine the arguments.

- Ethical compass, as I check whether the respondents/ informants/ user communities would object to the interpretations given in the published analyses.

- Open access and transparency of data by making the full dataset available in digital form in English and channelling it through the personal multilingual Wiki pages (currently 16 languages, with thanks to Elena Denisova-Schmidt).

- Any reader can experiment with organising the open access A to Z of informal practices database and suggest a way of structuring the material and identifying patterns. Responses from the wider public - the online encyclopaedia has around 5,000 visitors per month - have also been an important source of feedback.

Working together to create the online encyclopaedia has enabled hundreds of specific informal practices to be documented and underlying patterns of ambivalence to be identified in structuring the material for the published volumes. But how would I know if I was wrong in identifying these patterns? My own research has been informed by the method of the 'knowing smile', the smile of recognition, acknowledgement and complicity in an open secret about how things really work. This kind of tacit, unspoken communication tends to occur in settings where there is a division between us and them, insiders and outsiders, participants and observers. 'Us' and 'them' are as related as heads and tails- two sides of the same coin - which means it is essential to include the voice of the other when dealing with issues, especially complex issues. Attention to the knowing smile, sensitive to social and cultural contexts, makes the findings of the Global Informality Project more bulletproof. The focus on banal practices that escape regular attention, because they are the most routine aspect of the social and cultural life of societies, is also a method of suspending judgment before jumping to qualify informal practices as corrupt. These are everyday practices associated with qualifiers such as patronage, nepotism, favouritism, clientelism, and the use of social connections to obtain employment and promotions, to influence official decisions, or to circumvent formal procedures. At the same time, they remain close to some of the key challenges of today's world - corruption, terrorism, illegal immigration, human trafficking and cybercrime. In other words, micro-practices and patterns of human interdependence often fly under the radar while shaping large-scale phenomena. Keeping them separate, however, is essential to avoid misunderstandings. Such informal practices channel personal interests, but also facilitate the world's capacity for resilience - its default modus operandi.

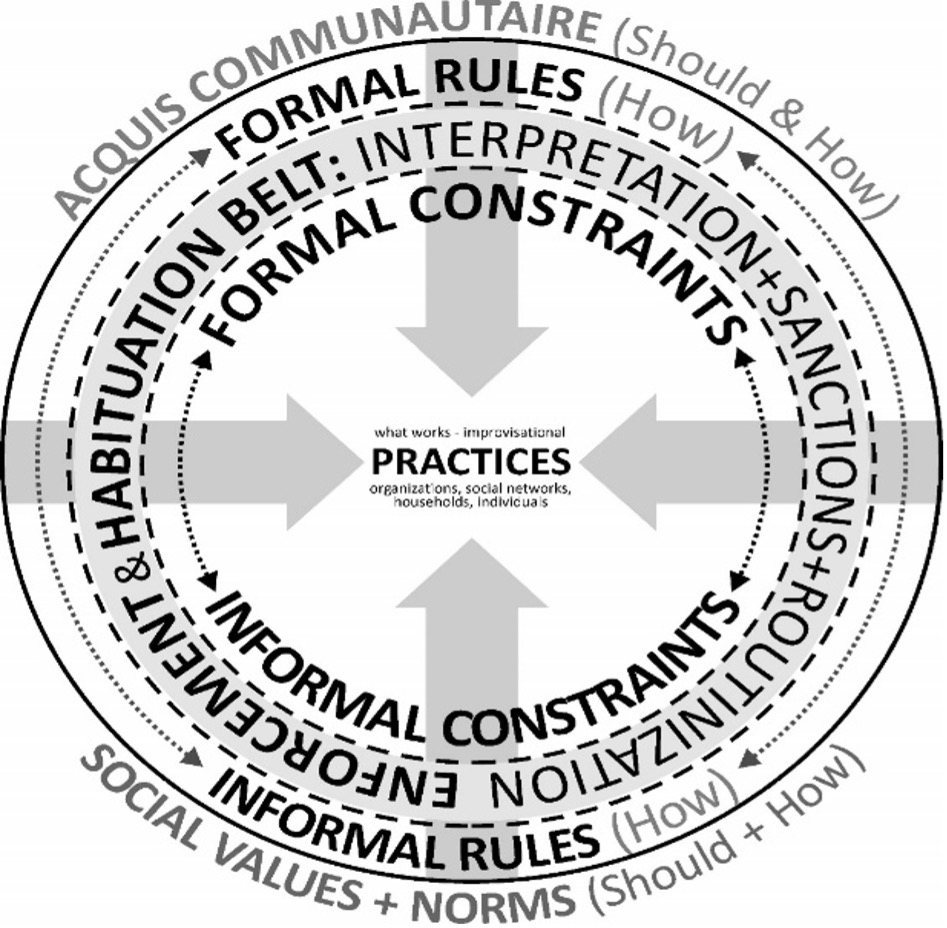

To reiterate the value of collaboration, let me give just two examples. It is now widely accepted that informality and governance are closely linked, but we know less about exactly how informal power operates. With Claudia Baez Camargo, we have examined the patterns of informal governance in regimes that are not politically or geographically similar: Mexico, Russia and Tanzania. Our findings were not only surprising: the instruments of informal governance - cooptation, control, camouflage - showed more similarities than expected, but also demonstrated the potential of cross-disciplinary and cross-regional research in producing and testing models that reflect both universal patterns and cultural specificities. In a larger scale comparative project on 'Closing the Gap Between Formal and Informal Institutions in the Western Balkans,' the mere fact that the model has emerged and was accepted by several research teams became a proof of concept, although it may never be possible to capture informality in all its aspects, because it is so complex and even network-based academic research has its limitations (see the model on Figure 4).

Figure 4. The INFORM model of formal/informal constraints determining human behaviour

Source: INFORM project, the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, GA No 693537. Newsletter No. 3.

How do you visualise something that tends to go unseen, unnoticed and undetected? Most of the practices in the three volumes of the Encyclopaedia are hidden from public view, shared as open secrets, and left unarticulated or unacknowledged in official discourse. Yet many contributors to the project have chosen to create visual shorthand to express the contexts in which informal practices take place. Visualisation is also an effective way of communicating insights into the workings of informality. The challenge of capturing and conveying the 'practical sense' or 'feel for the game' associated with informal power is captivating.

During my 2024 writing fellowship, I have experimented with conceptualising the informal power and its grip over people through visualisation, doing so in an art form. My first solo exhibition - "The System Made Me Do It" - is a constellation of entry points that could help tackle uncertainty and inform policies (see Figure 5). The visualisation was a shortcut that captured the complexity of informality while leaving it open: there is no definitive interpretation, as the ambivalence of informality is only resolved in a particular context, itself open to interpretation. The artistic method itself is drawn upon the ambivalence of material objects. It is easy to see the dual utility of a knife: a lifesaver in the hands of a surgeon, or a murder weapon in the hands of a criminal. It is a little harder to take a side in a hero/traitor dilemma, whereby the constituencies will be split or unable to categorise clearly. The logic of ambivalence, associated both with discomfort and creativity, has guided me in the search for materials for installations. I opted for those consistent with a shortcut/ what works/ actually-exists-in-practice approach to informality.

Figure 5. The poster of the exhibition

Source: Alena Ledeneva for Galerie de Buci, Paris.

Today I wonder if patterns of informal power that effectively serve as shortcuts in decision-making could be identified and interpreted by the AI. The ability of Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate text and images continues to grow, and the algorithm is already confident with themes of informality. An experimental feed of an art image of my work, entitled 'Succession,' into the ChatGPT4 produced interpretations that were adequate, relevant, and in tune with the tacit knowledge of power transfer captured in the piece (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Succession

Source: AlenaLedeneva.com/art. Succession. Wood, trophies.34x30x3 cm

The catalogue description of this piece:

Informal power is not transferable. There are no exit conditions: people are automatically recruited and presumed to play the system game to the end. Enabling succession is therefore problematic. Individual exit strategies are based on the degree of dissociation from the system: being compromised, being hooked, being pushed into internal emigration, preparing to leave, being pushed to leave, leaving voluntarily... The system is highly sensitive to identifying those who have lost their sense of the game or their sense of proportion.

Compare the patterns of informal power captured in my articulation of insights into the workings of informal power with the ChatGPT summary points about the importance of invisible dimensions of informal power transfer in organisations and business contexts:

"The composition suggests that while transferring informal power is possible, it requires careful management of both visible and invisible mechanisms of influence. The senior leader must provide visible support and endorsement to stabilize the emerging leader's position and legitimacy. Here are key considerations for a successful transfer:

Strengthening Networks: The emerging leader needs to build strong, reliable networks.

Visible Endorsement: The senior leader's support must be visible and unequivocal to signal legitimacy.

Gradual Transition: A step-by-step approach helps in gradually transferring influence while ensuring stability.

Mentorship: Continuous guidance and support from the senior leader are crucial.

By considering these aspects, the organization can ensure a smooth and effective transfer of informal power, maintaining stability and continuity within the business."

In many ways, the ChatGPT articulation of the informal power transfer is impressive, on the verge of policy recommendations and can be worked at further. The ability to identify tacit knowledge through AI may be an answer to the need to measure the immeasurable through digital technologies and big data analytics. As the results of the Global Informality Project have shown, capturing the ambivalence of informal behaviour, assessing both the supportive and subversive implications of informal practices, identifying the use of double standards in policy discourses, and identifying the role of positionality in distinguishing universal patterns from specific features are the future challenges in informality studies.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written during a one-month residency at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study in June 2024. I am grateful to Saadi Lahlou, Paulius Yamin and the team of the IEA-Paris for the wonderful welcome and the unique environment for creativity within the Paris IAS Ideas programme. The Paris Institute for Advanced Studies was both an intellectual and spatial starting point for the Global Informality Project, conceived at IEA-Paris in 2013-14. I am grateful for the Institute's continued support of the project in various forms: the 2018 book launch of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality (Vols 1-2) at Quai d'Anjou, support for the 'Out of walls' exhibition 'The System made me do it' at Galerie de Buci, 73 rue de Seine, 75006 Paris in June 2024, and Lisette Winkler's filming of the exhibition. Once the residence of Charles Baudelaire, himself a flaneur, the lonely wanderer of Parisian streets, almost a hitchhiker, the IEA-Paris is not unrelated to the third volume of the Encyclopaedia, A Hitchhiker's Guide to Informal Problem Solving in Human Life (UCL Press 2024).

For the data, I am indebted to scholars from all around the world who have contributed to the project in the last decade and the students of the Informal Practices MA course at University College London since 2000. Working at UCL, a truly global university, I was privileged to teach classes where each participant came from a different country and had specific concerns. So, the range of topics could be anything from arranged marriages, name changing to avoid ethnic cleansing and practices of covert modern slavery to astroturfing, catfishing and informal practices in cyberspace. Some of this research has been included in the online Encyclopaedia of Informality (in-formality.com), signed by 'Alumni of the UCL SSEES', and some have made it into the published volumes of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality.

Of course, I owe everything to my teachers. My training in Siberia (Novosibirsk University, Institute of Economics and Institute of Nuclear Physics) to believe that science has no boundaries, to ask questions and to be independent has shaped my career. During my PhD study in Cambridge, my fortnightly supervisions began with a question: "Are you sure that* blat* exists? No one here seems to have heard of it...' In response, I had to come up with seven pieces of evidence for the existence of blat, or the use of personal contacts to get things done in the Soviet Union.

I am indebted to my colleagues and my audiences. Along the way, I have been invited to give lectures, talks, seminars, and consultations. Each one has pushed me forward. Every unexpected question has changed the direction of future research. The editorial teams I had the pleasure to train and work with, their critical and creative input have made the project truly global. My project managers, Anna Bailey, Sheelagh Barron, Costanza Curro, Petra Matijevic, and Gian Marco Moise, have audited postgraduate courses on informal practices and developed their own excellent research.

I am very grateful to my reviewers and critics. Every unpublished text rejected by peers pushed for getting more evidence, care and sources. I have learned to cherish these rejections, collecting them in a separate file to reread for inspiration.

I must admit that my research was made possible by the degree of freedom and experimentation that only top institutions can allow and tolerate. The institutional support at UCL SSEES was paramount. I was encouraged to engage in research-led teaching and to train students as colleagues in team research projects, which effectively constituted the pilot phase of the Global Informality Project. Collaboration within UCL - UCL Digital Humanities-SSEES Internship Programme, Institute of Advanced Studies, FRINGE Centre, Bartlett and Slade, IT, UCL Library Copyright Office and the Open access team - has helped to address the challenge of the digital era. My participation in EU networking projects such as FP7 ANTICORRP, H2020 INFORM and H2020 MARKETS has significantly expanded my research network. The School of Slavonic and East European Studies provided an early seed grant and hosted an ANTICORRP fellow, Roxana Bratu, who worked on the first 'A Word of Mouth' call, helped build the database on informality and managed the editorial work. Elizabeth Teague joined the team and trained us in style and communication skills. Without the input of Petra Matijevic, an INFORM post-doctoral fellow and FRINGE researcher, who helped with the automation and dissemination strategy, improved the web design and led the development of the internship scheme, the online project www.in-formality.com would never have looked so professional. Gian Marco Moise was the genius behind the GIP Newsletters and helped the project grow in a timely and organised way.

My special thanks go to UCL Press for publishing the three volumes of the Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, making them open access and overseeing their distribution to over 200 countries around the world. The UCL Global Engagement Fund has supported the global events, facilitating future collaboration within the Global Informality research networks and further funding. Akosua Bonsu has been a champion and pioneer of the FRINGE projects. DFID UK, the British Academy, the Basel Institute of Governance, Integrity Action, the World Customs Organisation, INSEAD, ESCP Europe Paris campus, Wharton and Northeastern business schools, and other partners have supported the research and dissemination of the project's findings.