Acknowledgements

This paper was written during a 1-month residence at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study under the "Paris IAS Ideas" program.

My debts to Saadi Lahlou, Simon Luck, Paulius Yamin and the management, staff and colleagues of the Institut d'Etudes Avancée in Paris are very great, and I am delighted to be able to express them here, albeitinadequately.

Part One

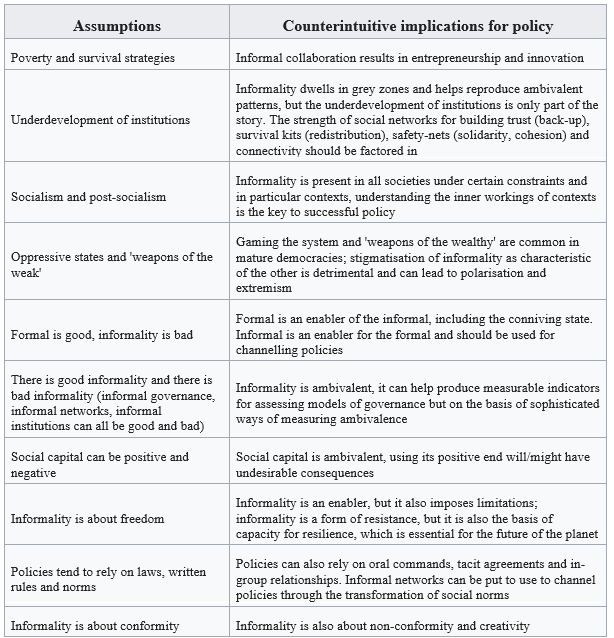

The classical, or if you like traditional, view of the "commons" dates back to the second half of the 19th century, and made it a site of social conflict and economic development. Beginning with Karl Marx and the British Christian socialists (Tawney and Hammonds and Webbs' parish welfare studies), the commons were conceived and reconstructed as the place where the English (and German) rural poor could find additional resources to their family budget, derived from the feudal framework of social relations in the countryside (Foster, Clark & Holleman, 2021; Bensaïd, 2007; Marx, 2007; Lascoumes & Zander, 1987; Tawney & Power, 1924; Tawney, 1912)1. The view was ex-post, i.e., from the end of the commons itself. This approach greatly influenced historical research, which read the long history of the European countryside as the progressive restriction of the spaces of indivision in English and European villages by the various enclosure movements of the open fields of medieval agriculture (Demélas & Vivier, 2003; Allen, 1992). The emphasis was on the conflict between social bodies that were like the social classes of the industrial economy. The emergence of social history, to which this research contributed greatly, partly corrected this picture from a better knowledge of a historical and sociological locus, the peasant community, which fed a considerable amount of research in the second half of the 20th century2. But above all, it intuited, even if not studied in depth, the role of customary law in the definition and management of the traditional commons: the words of Edward P. Thompson (2015) - "custom is the interface between practice and law" - opened the study of the commons to a new approach, one that was localised and attentive to popular politics and, above all, to law.

As is well known, this approach to the history of the commons has been challenged by an ahistorical but extremely concrete perspective, linked to the discussion and critique of the economic rationalism prevailing in the second half of the 20th century (Hardin, 1968). This perspective, supported by the works of Elinor and Vincent Ostrom, was defined as a critique of the theory and methodological assumptions of public choice in political science based on the belief that individuals are intrinsically motivated to self-organisation (Hudson, Rosenbloom & Cole, 2019; Ostrom, 1990). A large mass of case studies thus identified a specific species of commons - the "Common Pool Institution" - as a social dimension capable of rationally and sustainably managing local collective resources. This has given rise to a self-proclaimed interdisciplinary and applied science of the commons, which has mainly focused on the organisational aspects of the collective management of resources3.

This research perspective has profoundly influenced historical studies on the commons, which have mainly focused on management sources of those commons that were extremely well defined from a legal point of view4. Particularly in the Flemish and Dutch areas, a series of case studies explored specific situations of collective institutions in search of their ability to function as bodies capable of "risk reduction" in a system of agriculture exposed to the whim of events and economic circumstances; or in bodies capable of implementing "inclusive" policies that contrasted with the traditional Anglo-centric image of the commons as the resources of the poor (see for reference: De Keyzer, 2018; Bonan, 2016; De Moor, 2015; Berasain, 2008; Neeson, 1993).

The study of the commons has also been renewed in a different direction thanks to the renewal of legal history and the rediscovery of "European common law" due to an entire generation of European jurists (Iberian and Italian above all). The attention to the juridical dimension of common goods has benefited in particular from the rediscovery and reinterpretation of European common law and has encouraged the formation of new dynamic conceptions of the law in society5. It has brought to light the juridical pluralism inherent in ancient regime societies and made this a dynamic element for interpreting the commons (Herzog, 2018; Grossi, 2015; Herzog, 2015; Rodgers, 2011; Conte, 2009). The reinterpretation of terms such as "tradition" and "possession" has thus marked a new season of juridical research on the commons, and reflection on the legal categories with which to read collective property (Herzog, 2018; Grossi, 2015; Herzog, 2015; Rose, 2013; Rodgers, 2011; Conte, 2009; rose, 1994).. In this perspective, the commons are collective property, which is different from private and from public ownership. To understand the common property is necessary to understand "legal pluralism" and the "culture of possession" (prerogative given by acknowledgeduse). Without going into the discussion of whether collective property is a 'third type' of property besides private and public ownership, the legal-historical approach to the study of the commons is important because it shows how they are a legal and social construction, making their historical study urgent, but above all because the study of the commons makes it inevitable to construct non-anachronistic objects to study their otherness through the deconstruction of the categories employed by the various disciplinary traditions.

This perspective was meanwhile confirmed by criticism to the categories of economic historians, which assume the inevitability of the market and the increase in agricultural productivity as irreplaceable parameters, on the one hand, and the functioning of social systems associations alternative to the state on the other6. In any case, new possibilities for interpreting the commons in an "ethnographic" sense emerged with the birth and development of environmental sciences, especially when they use a diachronic approach to the study of present localised ecosystems. The delineation of a tradition of historical ecology of British origin represented a substantial criticism of lines of investigation which are both timeless and based on an idea of "nature" or "natural system" that clash with the historical documentation of agro-sylvo-pastoral practices. This approach concerns the idea of nature itself and replaces its misleading use in the study of present ecosystems with a more historical perspective assuming that, e.g., the vegetation canopy of a terrestrial ecosystem is an artifact (Cevasco, 2007; Balzaretti, Pearce, & Watkins, 2004; Moreno, 1990; Rackham, 2001; Rackham, 1990). This tradition of studies is based on the concept of plant (and animal) resources. Accordingly, a number of scholars have chosen to look at the commons as a system of resources: this neutral, "positive" category allows us to observe the agency to which common goods have historically been subject. It is therefore a matter of considering common goods as goods which were and are misused, and we know them through the uses to which they were subject (Ingold, 2011; Moreno & Raggio, 1999; Moreno & Raggio, 1992). Studying these resources and the practices of which they are the subject, is an absolutely indispensable aspect of research on commons.

These different approaches are based on, and to a certain extent depend on, historical sources. The historiography of the late 19th and early 20th century mainly used normative (e.g. by-laws) and legislative (parliamentary in the English case of the 18th century) sources, which gave a very rigid picture of local situations, including characteristics of the noble estates. Ostromian's historiography, on the other hand, privileged, as we have already mentioned, management sources linked to individual, well-documented cases (Laborda-Pemán & De Moor, 2016). By contrast, historiography linked to historical ecology has mainly used administrative and observational sources (Cevasco, 2007; Moreno, 1990). There are, however, other sources that provide us with extraordinarily evocative information about the commons and their function in local societies of the ancient regimes and the 19th century: these are the jurisdictional sources of various origins (e.g., local, provincial, secular and ecclesiastical). These sources are increasingly used by social historiography, even though they were judged as fragmentary and unrepresentative by 20^th^ historiographical traditions: sources that, although being fragmentary, report conflicts around the practices of which the commons were the scene. These conflicts are sometimes so insightful that they allow us extraordinarily illuminating glimpses.

Contestation of the right to collective use of one or more resources, contestation of the actors who claim the right: these and related disputes populate the archives of the old as well as the new regime. One might even go so far as to say that common goods are identified with such disputes and are very difficult to separate from them (Stopani, 2008).

The disputes surrounding the commons force us into a radical reversal of perspective: they show us that the commons "establish" communities rather than the other way around, the commons enabling the collective exploitation of resources. The commons are at the heart of local communities, and the meticulous study of the practices of which they are the subject invites us to a look as close as possible to the sources, to their protagonists. And to the context in which the conflicting actions take place. Now, the ethnographical reading of these actions show us precisely the protagonists, whose contours may also escape our interpretative categories and be, as they were, misunderstood.

Above all, such protagonists exhibit practices that, as we have said, "produce" locality, that is, they produce "natives" who are competent in local practices and in the requisites and rights necessary to exercise them (Torre, 2019; Appadurai, 1995). To fully understand this process, we must abandon a conception of local space as centred exclusively on the rural commune - an entity universally present but at the same time extraordinarily variable in Western societies and not only7 - and focus instead on the various actors who produced local space. In the medieval and modern period and at least until the end of the 19^th^ century, these jurisdictional sources present us with a panoply of groups, settlements, institutions, and associations (e.g., convents, confraternities, confrarie, farmsteads, hamlets, "sections of the commune", chapels, oratories, groups of relatives) that could claim rights over collective resources and legitimised their possession through legal ordinances and practical knowledge.

These sources thus make it necessary to adopt a spatial approach to the topographical scale, so as not to inadvertently confuse local territory and "commons", but rather to emphasise the moments and causes of tension between the various actors and the commons itself: in other words, the commons become the expression of local spatial practices.

The following considerations are based on materials relating to the Kingdom of Sardinia in the 18^th^ century and generated by the "Perequazione", a process of fiscal reform that imposed both to Savoy and Piedmont the registration of each administrative community to equalise taxes8. This material shows an agriculture still centred on the multiple use of resources, in which the commons played a central role in cushioning the consequences of unfavourable cycles (taking up abandoned lands or distributing uncultivated sections among the inhabitants) (Torre, 2021).

However, the Perequazione had an undeclared purpose, common to all European land registry operations of the period: to establish a territory to calculate a stable tax base. This implies the municipalisation of the commons. For this reason, and most importantly, the Piedmontese material shows specific protagonists at work, the inhabitants of the village hamlets, characteristic of a fragmentary or polycentric model of settlement. Their activity is clearly visible throughout the 18th century and the subject of an increasingly hostile attitude to the borgate (hamlets) by the central authorities in Turin towards the end of the century and during the revolutionary and Napoleonic periods. The enormous mass of documentation produced by the Perequazione thus shows increasing micro-territorial tensions: the hamlets - sub-units of the commune - resist to the "municipalisation" of the commons and claim the possession of "their own" commons: for instance in the 18^th^ century the state undermines the hamlets' prerogatives and judges define hamlets' commons as "private property" of the hamlet and tax it9. Tensions re-emerged strongly in the first half of the 19^th^ century, when the hamlets came to oppose decisively and sometimes violently projects of sale or rent of commons by the elites at the head of indebted communes (Torre, 2021).

We cannot help but wonder what this tension and conflict was based on. Certainly, the administrative sources of the Perequazione and the jurisdictional ones preserved for instance in the materials of the Intendenze of the Sardinian kingdom, show conflicting systems of classification of common resources. For the administration knowledge of the commons is based on the status of the land, of course, but the focus is mainly on cultivation destinations: commons are defined from time to time as wasteland, meadow, forest, clearance etc. The decisions that are made in cases of conflict show a proscriptive attitude towards destinations that are defined as "unproductive".

This classification of the commons is countered by a different classification by the villagers, which I would define as being based on "emic" or "internal" categories: who has access to the commons (Cottereau & Marzok, 2012; Pike, 1967; Archivio di Stato di Turin, 1828)10. For instance, the municipality of Azeglio (province of Ivrea) in the 1828 census of commons distinguished four types: a) commons "serving only to the pasture of the hamlet of ....."; b) "serving to the "pasture of the hamlet ... and inhabitants" (of the municipality); c) serving to the "common pasture of the inhabitants"; and, d) serving to the general "common pasture" (usually really unproductive land). Alongside very few and very small commons accessible to all the inhabitants of the commune, there are important commons pertaining to both a *borgata (*hamlet) and groups of borgate (hamlets), which give the term "commons" a scope significantly far removed from our imprecise notion of 'common'.

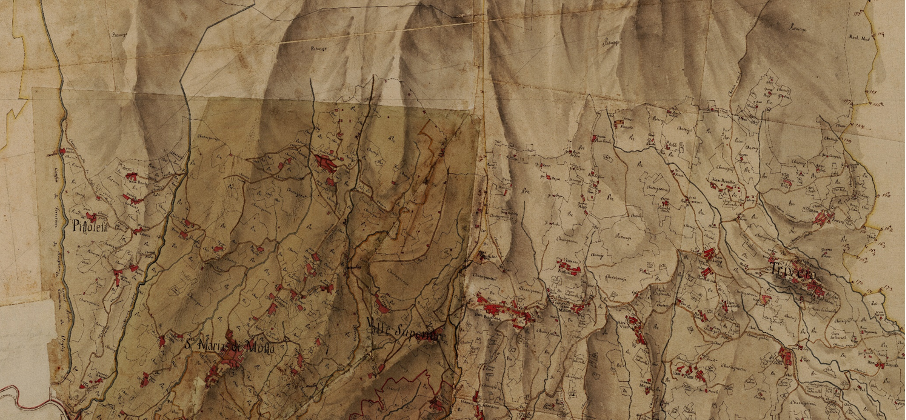

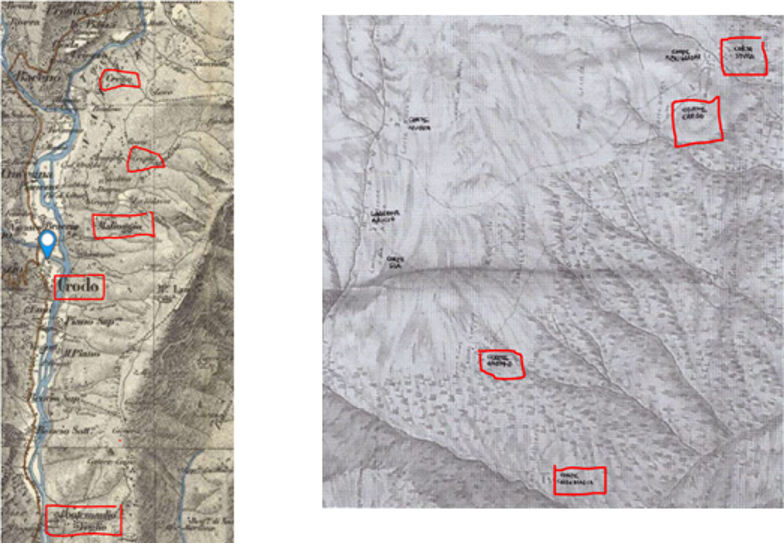

Figure 1 The fragmented, or polycentric settlement of the hamlets: the municipality of Trivero

(Archivio di Stato di Turin, Map of Mosso, 1809)

Figure 2 The hamlet of Bulliana, 1809

The strength and clarity with which this category appears in the documentation of the old and new regimes makes us wonder about its nature and function in local political and economic systems. On closer inspection, giving due consideration to the hamlet requires us to refocus the unit of analysis with which to read the life of the European countryside. Research projects of the past decades have attempted to do this, both in the sense of a critique of the unifying category of the peasant community through the revival of the methods of topographical analysis of documentation advanced and tested by the English Local History , and in the sense of the empirical exploration of settlement models of the medieval, modern, and contemporary ages (Tigrino, 2013)11. These research directions have shown the existence of fragmented or polycentric settlement models of the village of the ancient and new regimes radically different from the dichotomous models usually used to describe the countryside of the ancient regime - the nucleated model and the, opposed, dispersed village model. The fragmented or polycentric village to which I refer is a settlement that is articulated in a plurality of nuclei, none of which has for a long time the pre-eminence over the others. Only with the formation of the administrative municipalities in the modern and contemporary age were services (e.g., judicial, ecclesiastical, administrative in the strict sense) concentrated in one of the nuclei of the village (Torre, 1995; Torre, 1992)12. This is a process that has not so far received the attention it deserves, and this for several converging reasons.

To reconstruct the analytical image of the hamlet and the polycentric village, we have to resort to a number of indications from different fields of study. After the pioneering work of human geographers such as Albert Demangeon in the 1920s, and an ill-fated revival by G.T. Trewartha during the Second World War, Clifford Geertz used this category to interpret the Balinese village form, only recently have there been important attempts to return to the issue, prompted in part by the French discussion on the legal status of the commons (Puzenc & Charley D.L.M., 2020; Couturier & Vanuzem, 2020; Couturier, 2000; Cursente , 1999; Demangeon, 1927; Trewartha, 1943; Geertz, 1959)13.

The contribution of historical research on the commons to the knowledge of this specific aspect has been discontinuous or localised: areas such as Auvergne or north-western Italy have been the subject of timely analyses, as has Kabilia with important work by Alain Mahé14. In general, however, the literature on the commons instead focuses on the relationship between "community" and state, undervaluing the fact that communities are not cohesive (see Charbonnier, 2007; Laborda-Pemán & De Moor, 2016; Zink, 2000; Zink, 1997; Lemaître, 1981)15.

Important but specific events, such as the US government's attempt to build a network of hamlets to counter the Vietcong in the 1950s-1960s, do not seem to me to have yet received the attention they deserve16, just as the attempt to interpret hamlets as structures of political and cultural mediation does not seem to have been followed up, unfortunately (Cancian, 1996).

Thus, we must turn to historians of the medieval countryside and institutions to recognise the social and power processes that may have led to the formation of settlement beyond the classical opposition between the nuclearisation and dispersion of settlement that we have just discussed. On the one hand, historians of religious institutions such as Michel Lauwers have spoken of "inecclesiation", i.e. the increasingly capillary formation of religious centres in the countryside in the 11th-14th centuries, parallel if not concomitant with processes of "incellation" identified by historians such as Robert Fossier (Morsel, 2018, p.10-11). These processes of capillarisation of secular and ecclesiastical institutions give us a good idea of the tensions, including territorial tensions, that go hand in hand with greater institutional density.

However, the importance of the hamlet as a social structure has been emphasised mostly by the work of social historians, and above all by the studies related to the history of kinship that have clarified the nature and social function of the fragmented habitat. On the one hand, since the 1980s Gérard Delille had identified through a topographical study of ecclesiastical censuses (status animarum) specific spatial structures that fragmented the unity of the Campanian village and called them "quartiers lignagiers" (Delille, 1989; Delille, 1985). Osvaldo Raggio, in his study on the feud in the Liguria of the ancient regime, had also tried to map the surnames of the participants and came across characteristic spatial thickenings in demesne structures locally called "ville" (Raggio, 1990, p. 201). Kinship groups, therefore, would inhabit the hamlets of the fragmented or polycentric settlement. Bernard Dérouet has devoted decades of attention to these structures, attempting to clarify the link between spatial structure and the structure of interrelationships between people, and has identified the mechanism of succession of lineage hamlets as a fundamental social factor. The transmission between generations and between relatives and kindred created mechanisms of indivision that could even be the matrix of the very dimension of common. But, as Dérouet himself points out, these undivided structures did not, and still do not, provide for generalised access to undivided property, and thus by definition exclude the poor from the commons itself (Derouet, 1995; Zink, 1993).

These research indications thus identify in the spatialised social nexus of kinship a core of relations within the village, a factor of social and spatial tension. This is certainly true and proven, but it is my opinion that the hamlet may go beyond kinship and imply neighbourly relations that still elude systematic analysis in historical research and the social sciences (Sarti, 2003; Otero, 1632).

In the following pages I will therefore attempt to substantiate these lines of research and reflection. I will do so in two ways. On the one hand, I will try to substantiate the social aspects of the hamlet as a structure of kinship-neighbourly relations through a series of phenomena related to it. On the other, I will try to reflect on how the different elements of this analysis can be combined in time and space. Or rather, I will try to show how the ways in which all of these aspects combine in space and time can be interpreted morphologically, and I will attempt to define the process that their variation allows us to glimpse.

The aspects of the hamlet that seem to me to have emerged so far concern the legal, ritual, religious and redistributive spheres.

A) The legal aspect

Usually in legal and administrative literature, hamlets are treated as "dependencies" of the central body of the village, or the one that is emerging as such. An important exception existed, however: the Piedmontese jurist Nicolò Losa (Losaeus), author of one of the bestsellers in the albeit copious legal literature of the ancient régime, the De iure universitatum, published several times from 1604 onwards (Ingravalle & Malandrino, 2005; Losaeus, 1601; Torre, 2005, 2006)17. In this fundamental work, Losa sought to give legal substance to the bodies of the nascent village administrative community according to the approach inferable from Roman law and common law. But he also intended to recognise the legal personality of these social and spatial structures, which he referred to by the name of "villa" and recognised on the basis of the contiguous existence of at least five family nuclei (i.e., in extreme terms, three generations of the same family)18. On this basis, Losa suggested accepting the formal existence of hamlets as recognising a dialogical functioning within village administrative communities. And, in fact, as we shall see, this was the widespread demand in the European countryside. It was, however, reinforced by at least three other elements, which we mentioned above as qualifying aspects of the hamlet's existence.

B) The ritual aspect.

The hamlet has a specific ritual life, which is usually "embedded" in communal rituals, but which in specific situations - such as some Alpine and Apennine valleys and some pre-alpine areas - can be observed as an autonomous phenomenon, which I have already reported on elsewhere (Torre, 2011; 2009; 2007)19. It hinges around an associative body of a territorial nature, known in Italian as "confraria" (Latin confratria): this association is known for its connection with the feast of Pentecost, which it solemnises with a meal offered to all the natives of the locality, or of the municipality, or to all passers-by (Torre, 2023). This meal has a constant recipe, a soup of chickpeas (sometimes beans or other leguminous plants) and of course includes copious libations of wine (Pausanias, 2023; Thompson, 2016). This is an association whose importance has been underestimated due to its poorly emphasised character in the episcopal literature of the pastoral visitation - which nonetheless mentions it despite its non-devotional character20. The confraria is notable also for its distinctive iconography: a specific version of the image of the Trinity, the triandric or triadic one stressing the equality of the persons and emphasizing the central role of the Holy Spirit (Boespflug, 1984).

Figure 3 Joseph Calcius, Trinity, Blins, 1758

(Photo G. Olivero)

This aspect is of crucial importance, since it refers back to a quality of the third person of the Trinity, the pneuma, capable of infusing collegial gatherings with legitimacy, as countless images from the last centuries of the Middle Ages abundantly show (Poeck, 2003, pp. 8, 11, 26, 39, 65-6, 105, 115, 144, 206-207, 227, 263, 319; Black, 1996, p. 112).

Figure 4 Holy Ghost bewitching Toulouse's councillors, Annales de Toulouse, 1452-53

Archives Municipales de Toulouse, 1447.

This image, before being the object of harsh criticism by the 16th century heretics21 and being belatedly proscribed by pope Benedict XIV in 1741, experienced widespread diffusion: this is shown by the very few attempts to take a census of it, but it is above all shown by a figurative continuity that, after a great success in the 15th century, continued in some areas at least until the end of the ancient regime (Bertamini, 2000; Torre, 1985; Boespflug, 1984)22.

C) The religious aspect

Alongside the rituals and meals of the Holy Spirit confraria, the hamlet is distinguished by a specific religious aspect. It is very often endowed during the early modern age with a chapel, misleadingly defined by the post-Tridentine bishops as a "rural" or "in the fields". These holy buildings may be the property and responsibility of neighbours, or of a specific kinship. Their presence, as I have said, is carefully noted by bishops on pastoral visits in the early modern age, who are concerned not only with the "decency" of the liturgical and iconographic apparatus, but above all with the celebration of masses. Variable in extent, these are the true constant of religious life in the hamlet. They are not masses that can be defined as "devotional" in the language of the bishop but are the result of obligations deriving from testamentary bequests (Torre, 1985a; 1985b). These are the true characteristic of the religiousness of the hamlet oratory, and they conceal a more or less latent strategy: that of accumulating bequests and masses that could in the future allow the sustenance of a priest to give continuity to devotional life, and thus in time transform the oratory into a true, formal parish. Before reaching this goal, the existence of the oratory may give ceremonial recognition to the hamlet itself by making it the stage of a parish processions or the site of other festive ceremonies, such as the feast of the titular saint of the oratory itself.

In some cases, this strategy will be successful, and in the long run, the conquest of the parish may lead to the hamlet obtaining municipal status, which will then become capable of distributing the tax burdens required by the territorial state autonomously within itself.

D) The redistributive aspect

The last major aspect characterising the hamlet is a conspicuous redistributive activity. Mass bequests are only a part of this activity (the mass being a service for the local faithful), or only a part of the total bequests of a single testator. Another significant part is reserved for resource bequests involving the distribution of material goods to the inhabitants of the hamlet. These are mainly goods such as salt, or clogs, which were continually tied up throughout the ancient regime, giving rise to public distributions on particular holidays (All Souls' Day, Good Friday, etc.). But it is also the case, especially from the beginning of the 18th century, of foundations of grammar schools or scholarships for one kinship as well as all the inhabitants of the hamlet (Torre, 1985 a and b). Alongside, as a basso continuo, should be considered the activities of the confraria of the Holy Spirit, to which we have already alluded, which consist of a fundamental redistributive activity, that of providing a meal for all the inhabitants of the hamlet (Torre, 1985 a and b). The purpose of these activities is extremely clear: to define the scale, or the area within which certain resources can be redistributed. In other words, to create a social and spatial area of entitlement (Ferguson, 2015; S.Cerutti and I.Grangaud (ed.), 2017; E.C.Colombo (ed.), 2019).

It becomes immediately understandable, from this point of view, why, with the definitive establishment of the municipal institution during the 19th century, the hamlets tried to resist to the incorporation of their redistributive activities within the municipal charity, linked to the parish or the Congregation of Charity (Bordes, 1963). With the institutionalisation of the rural municipality, the exclusion of the hamlet inhabitants from the municipal council will create countless occasions for conflict or at least tension, and it will therefore become important to circumscribe a social area explicitly belonging to the hamlet inhabitants (Cassese, 2000; Bordes, 1972; 1963; Petracchi, 1962).

Part two

The considerations we have made so far identify a series of themes - from the process of succession to the politics of kinship, from legal recognition to ceremonial activities, from devotional activities to charitable ones - that allow us to understand the existence of a state, latent or explicit, of tension that we might define as territorial, or that in any case expresses itself on a territorial level. This tension, which in the light of these elements we might define as "structural" or inherent in the society of the ancient regime, nevertheless results in apparently discontinuous and contradictory outcomes. In some places, one or more hamlets obtain recognition and visibility in local life, participate in the deliberations of town councils, and feel they belong to them; in other places, they adopt measures that constantly reaffirm the hamlet's "separate" identity and go so far as to suggest the hamlet's achievement of ceremonial autonomy and further on of administrative autonomy with the creation of a new, proper municipality.

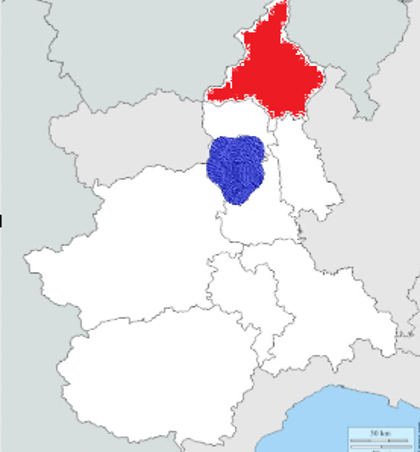

Figure 5 The Piedmont's provinces of Biella (blue) and Ossola (red)

Here I would like to briefly examine some of the outcomes that the territorial tension between hamlets and the rural commune has produced, and then try to explain its logic in morphological terms.

1 - Administrative reform and the end of the commons.

This affair concerns a late medieval political formation known as the "jurisdictional commune" of Vogogna (VCO). To understand the events surrounding the "jurisdictional commune" of Vogogna and its commons, it is necessary to analyse the spatial organisation of the community in detail. The "giurisdizione" of Vogogna was born between the 14^th^ and 15^th^ centuries: it was the ancient capital of the "Ferraria faction" of the medieval Ossola (IGC, 1973; AST, 1852)23. In modern times, it became a fief of the powerful Borromeo family (like much of the Ossola), but it was, as far as we can tell from the sources, a distant and weak administration, mainly concerned with the appointment of the giusdicente and the concessions of alluvial lands along the Toce valley24.

In the 18^th^ century the Ossola, until then a "separate land" of the Duchy of Milan, was incorporated into the Savoy state, the Kingdom of Sardinia, which with progressive administrative reforms aimed to dismantle this local administrative institution. The process of administrative reform was to end in 1819 with the loss of jurisdiction by Vogogna, which was transferred, based on military considerations, to the smaller village of Ornavasso, towards Lake Maggiore25. The central decades of the 18^th^ century thus witnessed a rapid succession of territorial changes. Until 1760, the jurisdictional commune (also called the "general commune") of Vogogna26 was divided into a series of communities with different statutes: ten lands that formed part of the actual commune, and "constituted a single territory" (red circle); three groups of lands that each had an autonomous territory - three villages to the south towards Lake Maggiore, eight villages arranged concentrically to the ten lands but with separate village territories, another eight villages in the Anzasca Valley that had autonomous territories (yellow circle)27. This was an unstable arrangement28: in 1722, on the occasion of the so-called "Teresian land register", the first group of the ten "united" lands had been surveyed in five different groups of maps29, in 1746 an even different configuration was presented30, in 1770 a new administrative arrangement was proposed, subdividing the territory of Vogogna into five jurisdictional-fiscal sections: fourteen lands that paid the "mensuale" (a Milanese tax) but did not participate in the deliberations of the council, three districts called Mergozzo, the Valle Anzasca, the "superior lands", the ten lands with the territory "hitherto united"31. Ten administrative municipalities were thus created in place of the ten lands of the council of Vogogna, but six maps were ordered to be drawn up, which would form the basis of future municipal aggregations and disintegrations: Vogogna with Prata and part of Capraga, Fomarco, Rumianca with Pieve, Megolo, Loro and Piana, Piedimulera. Finally, in 1775, when the Turin government issued the "Regulations of the Public", a fourth arrangement was formulated, abolishing the jurisdictional commune and creating many communes from the six maps of 1770 (Bianchetti, 1878, p.656-57). In this sense, the hamlets' path towards administrative autonomy seems accomplished and successful. However, throughout all these transformations, one condition remained constant: the impossibility of dividing the commons between the different new administrative units. An impossibility that was not unanimously shared32.

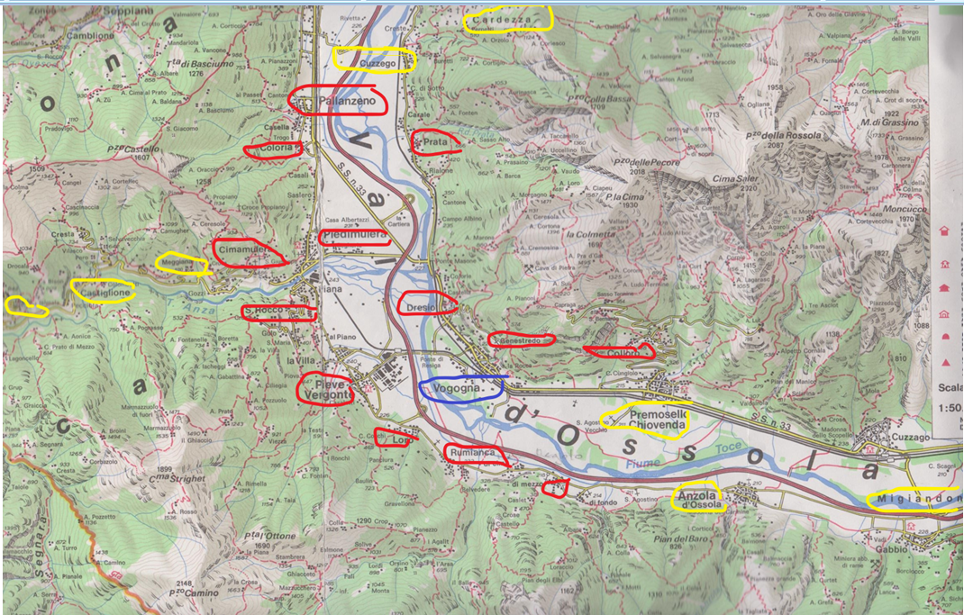

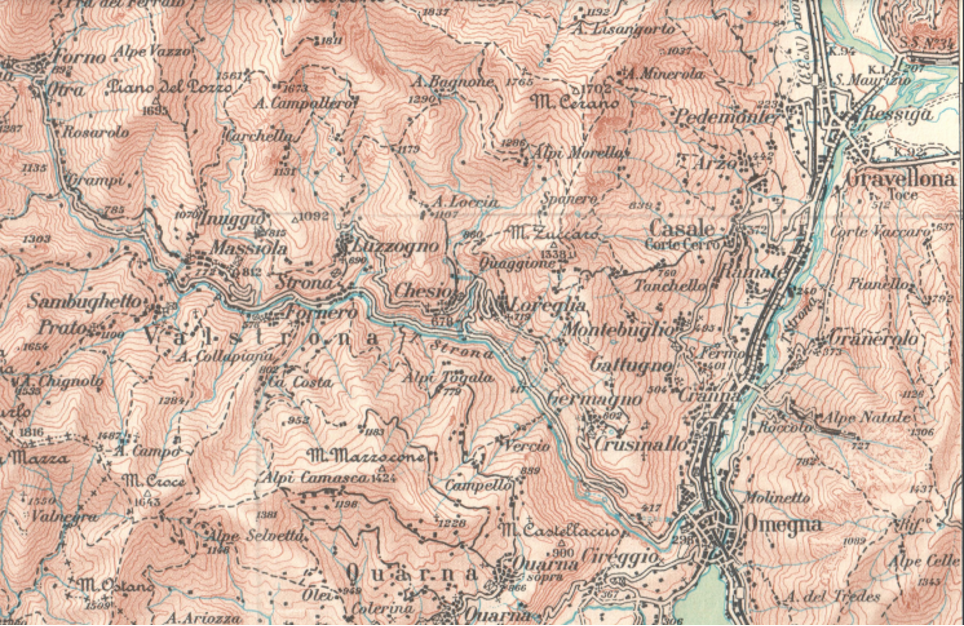

Figure 6 The Jurisdiction of Vogogna before 1775

In the division of 1775, however, "common property and pastures are not divided. For many years they were enjoyed promiscuously, with misappropriation of trees, crops, hedges and walls" (Bianchetti, 1878). This undividing was prolonged over time and still generates considerable uncertainty of attribution. In 1782, during the "Censimento de Boschi" (Census of the forests), in Cimamulera these properties were still defined as undivided with the 10 lands of Megolo, Romianca, Loro, Pieve, Fomarco, Piedimulera, Palanzeno and Prata33. Piedimulera does not have (any more) commons (it only has an uncovered pasture, i.e. uncultivated pastureland) and people obtain wood by cutting trees on their plots of land34. The wood used in Piedimulera to light three bread ovens (four since 1783) for use in the valleys and owned by the locals, comes from neighbouring communities.

The continuation of the commonality is then attested by other evidence. At Rumianca, the reply to the 1782 census of the woods was drafted during a meeting of the mayor (of Pieve) with the councillors of Rumianca and Mezzo (Megolo), with an additional councillor for each hamlet, held on 31 December, the last possible day to wait for the replies of Vogogna "with whom the lands are common"35. In 1784, in any case, the process of dividing common property, claiming ownership and possession of goods began. Conflicts are also reported due to inaccuracies in the land registers (Bianchetti, 1878). The process unraveled through an attempt at amicable settlement by Deputy Intendant Ignazio Roggero36 in 1785. Important processes of occupation and usurpation of common forests are reported, and the consequent equalisation of tax burdens triggered by this administrative reorganisation is invoked37. In at least one case, a conflict around the commons of Vogogna is documented: the Prata forest38. This is actually a mixed-culture area and perhaps the "best and largest portion" of the commune39. It should be valued in the apportionment of the commons of Vogogna, but it was usurped by private individuals who demanded recognition of the "improvements" in the event of taxation and opposed the "municipalisation" of the forest proposed by the Vice Intendancy of Pallanza. This conflict immediately had repercussions in Fomarco, where a "tumult of 15 chiefs of households to change the delegate for the division of the communes among the villas of Vogogna" and in Rumianca, where "the worst is feared"40. In 1787, the opposition of Rumianca and Prata to the division of communal property was reported. They complained of damages suffered by the communities due to usurpations and occupations that are mostly done by landless people. The situation became incandescent: again in 1787, it is claimed "to have seen from eight hundred to a thousand people ravaging the woods for more than a week, preceding a prohibition", in reality fomented by the kinship of the Tabacchi "special occupiers of communal goods, with some of their other adherents of a similar nature, who notoriously favoured their condition to the public detriment, and who succeeded in obtaining particular deputations to disrupt how they disrupted this division with excitements of disorder and popular upheaval as early as last February"41.

In reality, the conflict is more complex: it was Vogogna that wanted the division of common property. Prata's disputed goods were privatised or rather corporatised: "almost all of the said goods ... passed into the singular successors of the authors of the enclosures are finished and therefore the current possessors are for the most part corporations, including the church and other pious bodies of Prata"42. Again, in the same source, the prefect Roggiero di Pallanza indicates another cause at the basis of the conflict: the proposal to divide the common lands was made having "as a basis the divided 'estimo' and in proportion to the amount of the divided 'estimo' of each community"43, which evidently favoured the larger hamlets. During the Restoration, attempts were made to resolve the issue of usurpations with "perpetual emphyteusis" by the communes44.

Given the amount of information, it is necessary to analyse the individual settlements45. While in Fomarco, the management of communal forests is only documented from the beginning of the 20^th^century, in Rumianca, the 1782 census speaks of those "united for the common good" who would have sought to "resist the usurpations of communal property", but "not seeing themselves protected in the common lands, in which the private advantage was preferred to the public, and on the other hand observing the overburdening that came to the taxable part of the unequally apportioned common [therefore] only serving the arbitrary profit of the dispossessed". It is also argued that, if "each of the lands could take measures according to its share and according to the need and for that advantage that could be easily established", an adequate division of the common...[could] have produced the public good. Therefore, Rumianca cannot answer "the questions concerning the respective needs of the common quantity of cattle and the extension and quality of woods and pastures. The livestock is fed in the common territory of all the said ten lands promiscuously not only on the sandy municipal common, which gives scarce grasses, but rather on common grazing between all the said ten lands on divided meadows after the second hay has been cut until the rising spring, procuring some people even weak support with hay and grasses from the common mountains. Common grazing (on the divided meadows, which in summer are granted to people from other jurisdictions) is mainly for cattle for the benefit of the poor and the miserable. In the valley, the territory is poor in pastures, people use the mountain meadows46 and sheep are reported to be in the necessary quantity for clothing and to make money for certain needs and to graze in the low pastures from October to St Mark's (25 April). The administration believes that it is not expedient to fix the number of species of useful livestock because the floods, ruins and droughts that occur do not allow a probable estimate to be established.

The particular people who own forests on the mountains above their settlements make good use of them due to the scarcity of timber. They cut timber and wood for vines for themselves and to sell it to locals, because Rumianca is not bordered by foreign states. No wood is traded from the ten lands, only to locals by some particulars. There are common waste lands which are occupied by particulars. which do not pay anything, remaining the tax burden to the 'estimo' alive and taxable47.

Not differently, Vogogna confirmed that 'the communion of pastures and woods between the lands making up the commune of Vogogna has always been unaltered... even after the establishment of the maps' (i.e. cadasters); 'with the settlement of 1770 the division had been established but [it was] recognised as impracticable at the time, the communion was declared to be continued as it still exists today'48. With the census edict of 1775 the communal administration was interrupted, and in 1780 and 1781 the vice intendant was asked to resume the communal administration or proceed with the division. Therefore, not even Vogogna is certain of the common quantity of cattle, woods and pastures in the mountains. For the rest, Vogogna confirms Rumianca, word for word. "Of the meadowlands of the ten lands, however, only particular persons avail themselves"49. Instead, the whole commons (comunaglia) is exposed to the use of anyone. “The uncultivated land in the various places is occupied by many particulars, impossible to determine without legitimately authorised persons”. Vogogna reports that the “Mountain towards Cardezza of about 3,000 perches is disputed with Cardezza, which after a transaction in 1747 has devastated woods and continues to use hay and grasses, when the tax burden is all borne by Vogogna”50.

The scarcity of woods on the mountain flanking the village of Vogogna is noted. In the "opaque part" (the west side of the Toce valley) the quantity of woods is greater, with cuts interspersed a man's life span, but they are ruined by the bite of goats. The woods above the village are managed "jealously" by the respective owners, but the municipality has a shortage of wood, which it imports from other lands at great expense.

What is interesting about Rumianca and Vogogna's information, in any case, is the fact that they provide an interpretation of the current process, and this is the reason of these long quotations. Let us look at it carefully: according to Rumianca, "the territory is exposed to anyone's use, it is not possible to know whether there are any possible improvements or alienations, except after having made a legitimate division of common property among the ten lands"51. In the meantime, the first failures of the new arrangement were reported: "given the occupations that are made of common property both in the mountains and in the plain, the commons are neglected by the commune of these ten lands, because they lack common administrators, and [are] forbidden to unite, as it used to be the case in Vogogna"52. Faced with the common waste occupied by particulars that are common property, Vogogna states that in order to identify them, it would be necessary to have recourse to"persons legitimately authorised for all the ten lands"; it is not possible "to notify the occupiers, who are many in the entire district". However, a survey is requested53.

In the light of these complaints, one can understand the continuous local attempts to census the usurpations that punctuate the 19^th^ and 20^th^ centuries and that surface in the Archives for the Settlement of Civic Uses in Turin 54. Even the widespread conflict around the auctions for the attribution of the high pastures of Alpe Bongiolo, above Vogogna, can be interpreted in this light (the high pastures are in the hands of precise 'particulars').

In essence, the hamlets of the ancient jurisdictional commune of Vogogna managed during the 18^th^ century to free themselves from the guardianship of the major village. They concentrated charitable institutions within every hamlet55, but were unable to negotiate with Turin the presence of a jurisdictional authority appropriate to the scale of the commons, which were hoarded by segments of the local population.

2 - Separation between types of commons: dissolution of late medieval district for tax purposes, creation of municipalities as mobile federations of hamlets, centres of charitable institutions, section of external pastures and internal commons: the Valle Mosso (Biella province).

Relations between hamlets should not be imagined as relations between small municipalities, each clearly identified in its territory and institutions, but rather as intertwined and overlapping relations that define a specific form of political organisation (Torre, 2011; Torre, 2002; Torre & Lombardini, 1994; Bordone, 1994)).

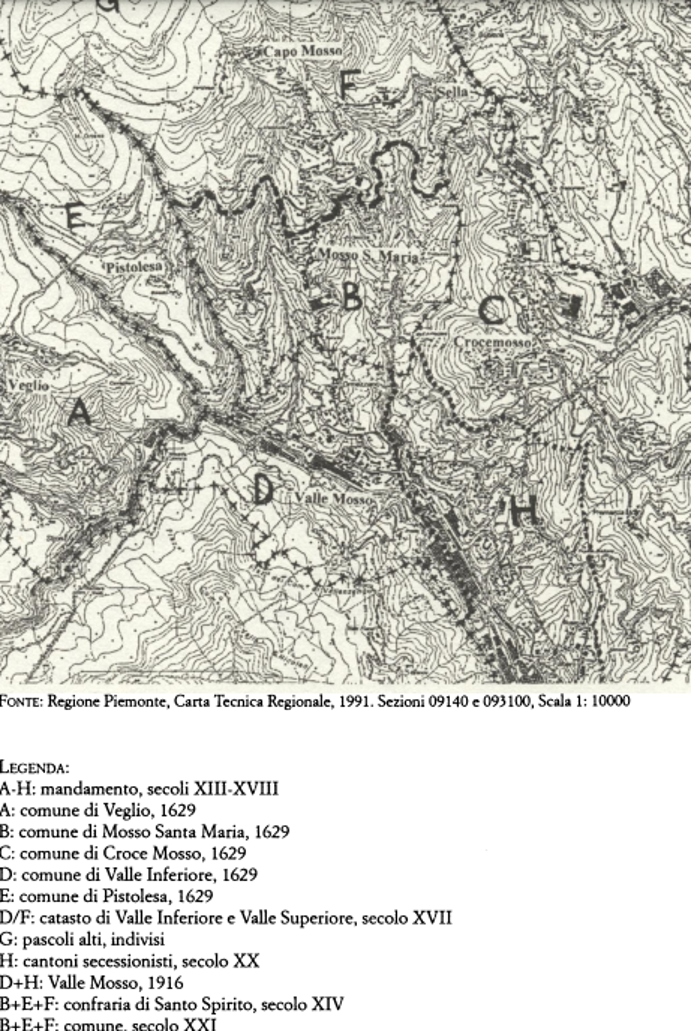

We can examine this problem through the (schematic) history of Valle Mosso, a small valley in the ancient Biella province, between Valle d'Aosta and Valsesia. It is, as is well known, the cradle of Italian industrialization. Less well known is the fact that it is an area of very high settlement fragmentation. The valley is composed of four (today three56 municipalities but comprises at least fifty hamlets characterised by the typical parental base57. In modern times, the political organisation of the valley is based on the - mobile - coalitions of hamlets (Fig. 7). These coalitions are made possible by the fact that the hamlets have a series of rights linked to the exploitation of resources, ritual institutions and economic, administrative and for a time even ideological orientations, which bring them closer to some of the valley's contiguous hamlets, while distancing them from others.

Internal relations within the valley (and with neighbouring valleys, of course) were transcribed almost exclusively by the Savoy state, which has had unchallenged jurisdiction since the 14th century, with a precise if ambitious aim: to obtain, for tax purposes, the hiving off the ancient valley unit, the Mandamento di Mosso, to form fiscally responsible communities (Sturani, 2021). Very schematically, this process went through a trisecular series of failures: however, the resistance of the local populations seems to be due not so much to the cultural distance from Turin as to the complexity of the possessory regime.

The Savoy demand for the separation of the Mandamento (A-H on the map) arose from financial problems. In the 1620s, the Savoy state experienced a very serious crisis, which led to the civil war of 1639-42 -still misunderstood-- (Cerutti, 1992). To raise money, Charles Emmanuel I proposed to create six administrative communities resulting from a federation, or summation, of contiguous hamlets. At the same time, he tried to establish a dual regime of pasture exploitation: the higher ones, called "disjunct" (distant, separated from the hamlets) were rented out, while the neighbouring ones, called "simultenenti", or contiguous, were allocated to common grazing and other practices, such as the collection of bark for dyeing58.

The proposed division comes up against enormous and insurmountable difficulties, since the local populations practice multiple, and contradictory, criteria for apportioning expenses. The first criterion is that of dividing tax burdens by counting in Ducati (points of account): the territory is made up of a totality of points (quotas), and each of the hamlets represents a part of it. In the mid-seventeenth century, there are 120 Ducati and each hamlet has a share, in relation to its political bargaining power within the valley, the Mandamento di Mosso. However, there is another distribution criterion, which is based on the tax burden that each hamlet must bear on its non-immune (i.e. non-contested and non-ecclesiastical) territory. As one might expect, the two criteria do not coincide at all, and an important commune (in the 17^th^ century) such as Croce (Mosso) alone accounts for a quarter of the Ducati, while paying only a sixth of the tax burden. But these are not the only existing criteria of identity and representation. Alongside this, there are the confrarias of Santo Spirito, which we could define as amphibious, in the sense that they can (depending on the confraria) have a cantonal basis (1 confraria=1 chapel =1 hamlet), or provide for a pluri-hamlet basis (e.g., the confraria of Santa Maria unites the hamlets of Pistolesa, Santa Maria itself and Valle Superiore: B+E+F in the map). Other hamlets are also characterised by common registration practices: some hamlets, such as Valle Superiore and Valle Inferiore (D and F), draw up their land registers in common. The geography of the parishes, then, does not coincide at all with that of the hamlets and confrarias.

There are also divisions, and solidarities, generated by the use of resources. It is obviously impossible here to account for the almost inextricable intertwining of such interests, but it is essential to point out how pastures, forests and streams are subject to contradictory and conflicting uses. Pastures - particularly high pastures -, for instance, can be rented out to farmers-entrepreneurs: in this case, the owners are against any unbundling because they believe that the income from renting out the whole of the pastures is higher than that from their individual parts. Furthermore, the fact that pastures (as well as woods) are also owned by confrarias and charitable institutions on a hamlet or inter-hamlet (but not communal) basis, implies that the sale of pastures by communes concerns assets and usage rights owned by other parties, which are not questioned.

Forests, for example, are used to produce timber (coppices). From at least the middle of the 17^th^ century, it is used in an industrial sense as raw material for dyeing. Moreover, these uses contrast both with the use of beech forests as pasture woodland, and with the cultivation of chestnut forests, which are mainly used for food and grazing (Rackham, 1986; 1982). The conflict over water use, on the other hand, is more classic, and pits industrialists against farmers, especially from a fiscal point of view. Finally, one must not forget traditional conflicts over rights of way, which in a world populated by flocks both on pastures and in forests are of the highest importance.

Fig. 7 Valle Mosso, Regione Piemonte, Carta Tecnica Regionale

The truly remarkable complexity of the situation leads to the transcription of an extraordinary document: in 1773 (150 years after the first proposal of division!), hamlets, municipalities and charitable institutions negotiated among themselves, in the presence of the intendant of the province of Biella, the extension of their respective territories59. The intendant, faced with the difficulty of imposing just one of the criteria for dividing the territory, proposed to the populations to choose it autonomously, with a largely predictable failure outcome. In return, the transcript makes the 1773 negotiation a "Savoyard" document that demonstrates Turin's jurisdiction over (formally ecclesiastical) charitable and parochial institutions, as well as arbitrator of the fate of the tenant- stock farmers. But above all, the process failed because Turin chose the wrong interlocutors: it was not the commune that was the basic territorial unit of the valley (and of the Biella area in general), but the hamlet.

Hamlets are also the protagonist of later transformations. An innovative study, which we owe to F. Ramella (1984 and 2022), showed how the populations of the various hamlets controlled (or tried to control despite the merchant-entrepreneurs) the growth of textile production during the industrialisation phase of the area. It is interesting, from our point of view, to note how control took place both through a precise form of domestic production and, later, by attributing a parental-hamlet basis to both the labour market in the hamlets and the organisation of consumption.

The hamlet's weight was felt not only in the organisation of production activities, but also in the creation of local political categories, which did not necessarily flow into the organisation of the incipient workers' movement in the area. Meanwhile, the industrialisation of the valley rather accelerated than hindered the speed of formation of coalitions between hamlets. For example, the eighteenth- and nineteenth century splitting of the Mandamento was sponsored by the municipality most involved in manufacturing and dyeing activities, Croce Mosso (C): the aim was to exploit its greater political weight (Ducati) to obtain more pastureland for rent. Croce ended up losing access to the woods essential for industrial activities, which were taken over by an adjoining hamlet, Capo Mosso (in the territory of F).

Croce Mosso's effort failed (for the reasons we have briefly outlined) and resulted in a new configuration of the valley. Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, the municipality of Croce undergoes a process of internal fission, and its lower (and southern) hamlets attempt to unite with the hamlet located along the river, where the new manufacturing activities are being concentrated (Valle Inferiore, D). This is clearly a resurgence of kinship initiative, which dominates the eight secessionist hamlets (H). It will find a listening ear in the Fascist territorial reforms, which in 1934 proceeded with the incorporation60. The language on the basis of which the secessionists win is that of ritual. In fact, these hamlets, made up of parental groups, gave birth to a new parish in 1954, and again in 1963, the bishop of Biella included another oratory with the hamlet of the same name in the new parish jurisdiction. The new parish priest was in any case obliged to bring festive mass to the hamlets' oratories, and to confirm the ancient traditions regarding burials and marriages (Lebole, 1970). As if to say that the presence of a larger parish unit should not contradict the basic identity, that of the hamlet.

This territorial regrouping is undoubtedly linked to the progressive allocation along the valley floor of the previously dispersed manufacturing activities, but it expresses a conception of the political community well known to the inhabitants of the valley: the attraction to Valle Inferiore is expressed not only in the ritual sphere, but also in the charitable sphere, which has constituted - through the confrarias of the Holy Spirit - the local political identity for centuries. When the aforementioned hamlets demanded (1890-93) the separation from Croce, Valle Inferiore supported them on the basis that its inhabitants already participated in the charitable privileges with which the rich municipality was endowed. The change of name in 1916 (from Valle Inferiore to Valle Mosso: D+H) seems to translate this change of status of the hamlet, linked to manufacturing activity. Alongside these reasons, other reasons defined as topographical are presented: the settlements of the two municipalities are mixed to form "a single building mosaic... everyone... believes they are in Vallemosso finding themselves in Crocemosso" (Lebole, 1970). The secessionist hamlets protagonists of the first request of 1890 (=Prelle and others) are those "that gather all the clothing industry...in the orbit of Vallemosso" (Lebole, 1970). But there is no lack of ceremonial reasons: the population of the secessionist hamlets, it is claimed, celebrate marriages in Vallemosso.

If the hamlet is therefore the true political unity of the valley, it is not surprising that its weight makes itself felt anyway and everywhere, and that it attempts to translate into its language processes that are foreign to it. Thus, Pietro Sella, the standard-bearer of modernity, the man who was able to introduce the steam engines heralding the new industrialisation into the valley, had a plaque in Valle Mosso, the industrial hamlet, when he died. This provoked reactions from the excluded, which resulted in a celebratory book. There were those who proposed erecting 'at least four gravestones' in his honor, as many as there were hamlets that his existence had touched. The one where he had been born (Valle Superiore, today Sella di Mosso, in the parish of Mosso Santa Maria), the one where he had developed his industrial activities (the 'old machinery' in Croce Mosso) and the one where he is buried (Mosso Santa Maria).

In any case, this is not a forgotten past, but a political system that is still fully operational: this is suggested by the merger of the municipalities of Pistolesa and Mosso Santa Maria, initiated after World War II and concluded with a referendum in January 200061. Justified by the depopulation of the mountain area, the merger seems to recall more persistent values linked to the historical production of citizenship and the suggestion of territorial loyalties on the part of local institutions. An episode from 1835 illustrates this aspect well: when the decision was made to build the new cemetery of Santa Maria, on which the municipalities of Valle Superiore and Pistolesa depended, it was realised that there was no principle to establish whether the expenditure of the cemetery should have the predial tribute or the population as its basis. "Equity and justice" advised sticking to the population (and therefore ignoring land ownership data and tax roll registration) to recognise the territorial scope of a confraria of Santo Spirito, attested since the 13th century, whose jurisdiction would include the territory common to the three hamlets.

Unlike the case of Vogogna, therefore, the Valle Mosso affair shows a different solution to the problem of the relationship of possession between hamlets and commons. Here the hamlets maintain control of the commons through the separation between external commons and internal commons, the former rented out to foreign stock-farmers, the latter in the hands of the inhabitants of the individual hamlets for their daily needs and the feeding of the (few) animals they own (Greer, 2018, chap.8). It is significant, however, that the former - with the profound economic and social upheaval of industrialisation - were abandoned in the course of the 19th century and became the object of a patrimonialisation policy and tourist redevelopment in the first half of the 20th century (Torre, 2019).

3 - Communal commons managed by a federation of hamlets;

The commune of Crodo, a locality in the Upper Ossola followed the fate of Vogogna and its hamlets but the commune has managed to retain control of its external commons to this day. These mainly consist of a large alpine pasture - Alpe Cravairola or Cravariola - located beyond the watershed in Valle Maggia, in the hinterland of Locarno, above Lake Maggiore and Canton Ticino in Italian Switzerland (Beltrametti, 2013; Lowenthal, 2004)62.

The ownership of Cravairola by the commune of Crodo is the result of an acquisition strategy dating back to at least the 14th century. In that period, what in the documents calls itself "the municipality of Crodo" is the protagonist of purchases of part of the Alpe Cravairola and leases of parts or the entire Alpe to individuals or families, usually the same ones from whom it had purchased63. People of Crodo or from the nearby hamlet Pontemaglio ceded to the commune their property rights to the mountain pasture in order to receive it in concession and become a shareholder64.

In modern times, grazing appears continuously as a property claimed by the 'commune' of Crodo, but it is also continuously claimed by the now Swiss commune of Campo Valmaggia and its hamlets65. It is important to ask ourselves what that term, commune, means. While we today attribute to this term a very precise meaning of a territorial institution with a precise spatial and administrative profile, in late medieval documentation Crodo appears as a neighbourhood. It is called the "Quarter", sometimes also in the plural "Quarters", of Crodo. It has an annual Consul, surrounded by a plurality of "aldermen", who draw up notarial deeds in the name of the district. These aldermen invariably specify their (micro)locality of origin: the names that recur are those of Crego, Maglioggio and other less frequent66. It would seem, from these tenuous clues, that there exists a municipal institution, collectively represented by these individuals, who in each case refer to a specific locality[^67]. There are no formal traces of this organisation: we can individualise it by induction through a "realistic decipherment" of the documentation. It consists of material illustrating episodes of the territorial conflict between Crodo and Campo. On the Swiss side, there are no traces of the conflict except for the presence of the late 19^th^ century printed sentence, which however lacks the accompanying annexes68. In the municipal archives of Crodo, ~~on the ~~on the one hand, we can see that the dispute with Campo Valle Maggia is accompanied by others with other neighbouring municipalities: Crodo is in dispute with all the surrounding communities over various portions of territory on their mutual borders69. In short, we find ourselves in a mobile territory, full of tensions between micro-settlements70.

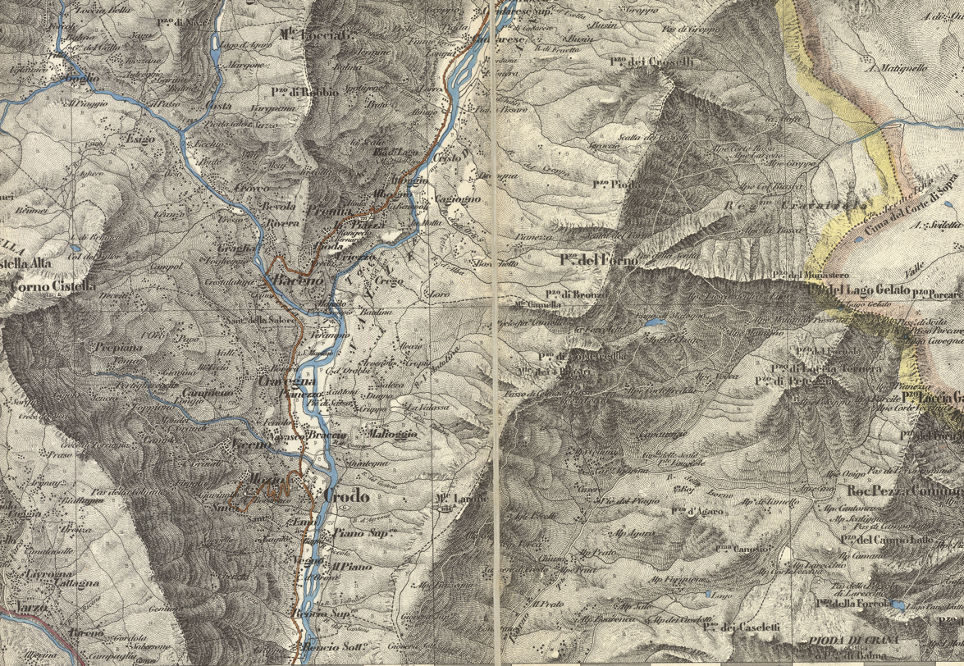

Figure 8 Crodo and Cravairola in AST, Gran Carta degli Stati di Terraferma, 1852

(No citation found)

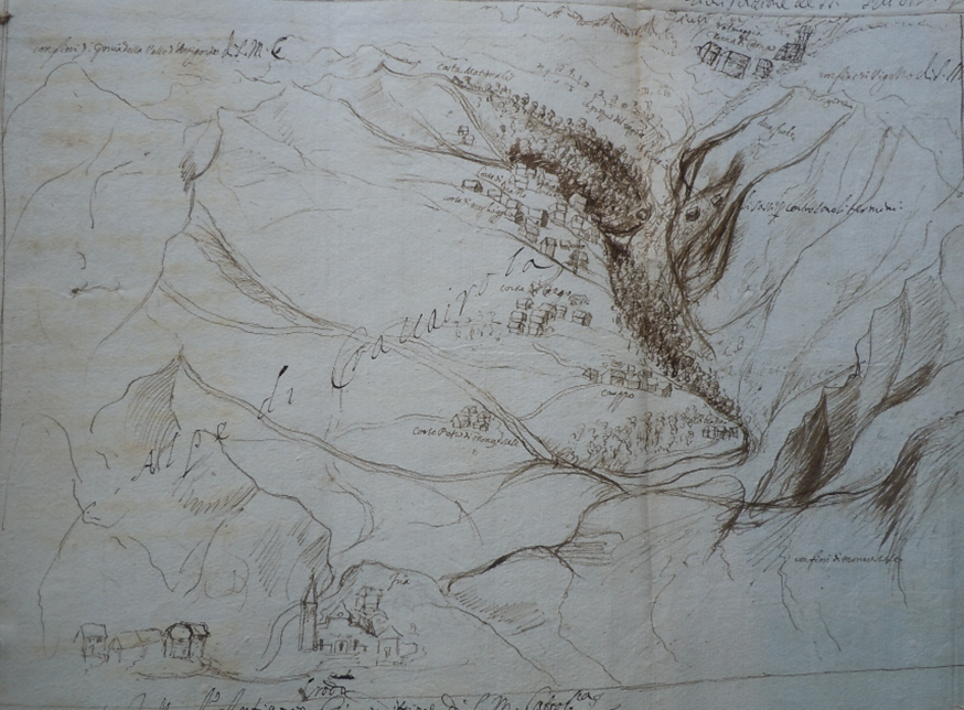

Of all the aspects of pasture management that the documentation brings to light, one, essential, concerns the way in which the Alpe was inhabited. The Cravairola is a densely inhabited place, at least in summer. It is populated by groups of "Cascine" where we can imagine temporary farming activities, but also by more modest and smaller "Casere" - sort of dairy farmhouses and sheepfolds in masonry - of which we have detailed descriptions because they were the scene of robberies, violence, and various attacks. Casere are not isolated, but are grouped together in "Corti" (in the masculine form), which have a name (see Tab. 1)71. These names follow one another in the various episodes without being able to identify them, until, in 1642, a first glance from the outside gives a (topo)graphic representation of them, finally associating the names with locations72. We thus learn that a very precise series of "corti" populate the Alpe; but above all, that these Corti correspond to localities in the Antigorio Valley, members of the Crodo district. Thus, the men and herds and/or flocks of Crodo (the central hamlet) inhabit the Groppo corte located in the centre of the basin. Lower down, men from Pontemaglio - who share the possession of the Alpe with Crodo - inhabit the Collobiasca corte. But higher up, men from Montecrestese, another village uninvolved in territorial conflicts, inhabit the corte Rosso73. Halfway up, the "Corte" of Crego, those of Brazzo, Crupo and Maglioggio house men and animals from the respective hamlets.

Figure 9 Map of Judge Ayala, 1642, AST, Confini con gli Svizzeri (detail)

But the most striking case is that of the hamlet of Pontemaglio, which shares possession of the Cravairola with Crodo: Pontemaglio is not a municipality, but a hamlet of Crevola (today Crevoladossola). The possession of Cravairola by the hamlet of Pontemaglio is not in dispute, and it should be remembered that the 14^th^-century purchases of pastureland by Crodo took place precisely at its expense. Later in the 18^th^ century, during a long dispute with Pontemaglio, Crodo scornfully declared that Pontemaglio had no rights as a community, but only as a hamlet. The detail is of paramount importance, and goes beyond the possible rhetorical nature of the statement, likely in the midst of a legal dispute: it implies the fact that the owners of the alpine pasture were a series of hamlets arranged along the Toce valley, and that Crodo's purchases during the 14^th^ and 15^th^ centuries were part not only of a land acquisition strategy, but of a strategy of political pre-eminence over the other co-owning hamlets.

This spatial organisation (and representation) evokes fundamental examples of 19^th^ and 20^th^ century social science, which suggested that the morphology of villages is related to the conception of the firmament and the universe : they are, in essence, a representation of social structure (Durkheim & Mauss, 1901)74. This fact is fundamental. It expresses in a complete, and finally explicit manner, an organisational mode, which has at its centre the hamlets of the Alpine valley. A later testimony, from the middle of the 18th century, specifies how it was not binding for the individual cheesemaker and the boy in his employ to occupy the farmsteads of its "corte", but how it was a preferential modality75.

Figure 10 The two villages: Lower (Left) and Upper (Right). Gran Carta, cit. 1852, and Mappa dell'ingegnere Sottis, 1759 (AST, Confini con gli Svizzeri)

What characterises Alpe Cravairola, in any case, is the fact that this representation of space fades over time. Images after 1640 do not show the organisation attested in the mid-seventeenth century with such clarity. It is as if the meaning of the naming of the "corti" lost its territorial and hamlet connotation. The Habsburg map of 1722, of great graphic effectiveness and precision, unfortunately does not show the names of the corti76. A Savoy map of 1759 shows us partly changed, partly new names. In 1759, the corti of the main hamlets remain: Crodo "centre" (Groppo), Crego, Montecrestese, Pontemaglio. Maglioggio disappeared, but new ones appeared, including a significant "Corte Nuovo". Others have changed their names, but it should be noted that the new ones no longer have a territorial reference: Corte Brazzo has probably become Corte Stua. Crego disappeared from 19th century military maps77, and today none of the surviving Alps retains a name that can be traced back to the territorial arrangement we are describing78.

Table 1 Cravairoila Corti's names in the different maps

The disappearance of the names of hamlets from the alpine toponymy is a sign of a significant change in the political structure of the Antigorio Valley between the end of the Middle Ages and the modern age: it describes the birth of the municipality of Crodo in the modern age.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the valley was an institutional political body in its own right: it had statutes79 and its own jurisdictional bodies, particularly the Judge residing in Crodo. We have an 18^th^ century description of the actual functioning of this body, which allows us to grasp all its internal tensions. It was written in 1716, during a dispute between Cravegna and Crodo over the taxation of men from both places80. The deputies of the valley maintain that it is composed of four small "terzelli" (quarters), the lands of Cravegna, Mozio and Viceno, form one of the said terzelli, and Baceno and Cravo, which form the second. Premia forms the third [while Crodo forms the fourth]. The terzelli "call them all communities of unequal territory and consequently of unequal tax assessment, [the valley] has always been used to dividing all the extraordinary loads pertaining to that valley into four equal parts in proportion to the number of the said terzelli or communities that make it up, regardless of the notable inequality of territory that exists between them, the smaller terzelli bringing equal burdens, because many of the particulars of one terzello possess goods in the terzello of others, but these never concur in the bearing and payment of such burdens, except for the goods that each one possesses in its own terzello, thus constituting a kind of tax equality between the greater and smaller terzelli"81.

This is a succinct description of a political body of a territorial nature: the valley is divided into territorial districts composed of a multiplicity of settlements of varying size grouped into districts -the terzelli, in fact-- (Della Misericordia, 2006; Bonini, 1976). They balance out among themselves the fiscal inequalities determined by marriages, displacements, and the infinite accidents of social life: one is taxed on the basis of the property one owns in one's place of birth and not on the basis of what one owns elsewhere in the valley.

The structure of this body has major implications. Crodo is thus a terzello of the Antigorio Valley, and is composed of a plurality of settlements: according to the Status Animarum, compiled every 5-10 years from 165682, there are 23 hamlets in all83, divided into "citra aquam" to the west of the Toce and "ultra aquam" to the east. The two parts are not symmetrical, and seem to have two distinct features: while the first, which includes the central hamlet of Crodo, sees the formation of new settlements and nuclei, even microscopic ones, the second appears to be composed of a fixed number of settlements, and these are those that give their name to Alpe Cravairola surveyed by podesta Ayala in 1642: Brazzo, Crego, Maglioggio, Cruppo or Crupio, etc84. In addition, each hamlet was found to have a constant number of households for two centuries (Chiesi, 2019; Lorenzetii & Merzario, 2005). I would like to emphasise a fact that seems to me to be of great importance: in the first surveys, dating back to the second half of the 17th century, Crodo is still called "Villa", like the other settlements, a term that disappears only in the 18^th^ century.

With such a settlement network, it is not surprising that it is these nuclei that define the political identity of individuals: between the end of the 15^th^ and 17^th^ centuries, the people who appear in notarial deeds - public and private - define themselves through their hamlets' affiliation85. Crodo is therefore a "vicinanza", in the institutional sense but also in the spatial sense: it is a summation of hamlets. This fact has a direct implication on the way the management of Alpe Cravairola is represented in Crodo. We cannot be surprised, therefore, that even in the mid-18^th^ century some witnesses, who originate from the hamlet of Brazzo, say of Cravairola "that said Alpe [is] in communion with those of Crodo"86. I do not believe that the use of the concept of "communion" is coincidental: as the inhabitants of Pontemaglio also insist in their claims against Crodo, it implies (at least) two different equal subjects associating themselves87: it perfectly expresses the conception of settlements with equal rights, some of which were united in the terzello referred to above.

Let us return again to the Valley, its structure, and its evolution. The documentation shows how it was above all the movement of people that created dynamics that were difficult to govern. According to the authors of the plea of 1716 from which we started, Crodo 'has taken it upon itself to oblige the particulars of the other aforementioned terzelli, which today possess in that of Crodo, to repay the relevant sums said to have been paid by the said community of Crodo for its fourth part paid by way of extraordinary charges from the year 1692 to this part'88. Crodo is establishing itself as a central locality and intends to subject the inhabitants of the valley who own land in its territory to the tax.

We cannot but wonder whether the emergence of Crodo as a central location had implications for the management of the alpine pasture. In the second half of the 19th century, the only surviving documents related to grazing at Cravariola show that it is organised by "casate" (lit. houses). These are identified by surnames rather than, as two or three centuries earlier, by locality. That is, the Vincler house is mentioned, as well as those of Vincenzo Giovaninetti, Matteo Minetti, perhaps Matteo Ronchi, and the lawyer Guglielmi. Sometimes the surname is accompanied by the diction and companions (compadri)., or, in only one case (linked to the lawyer Guglielmi, one of the most prominent figures in the village) company89. Individual homes or families entrusted few livestock - from one to five cattle and a few goats, sometimes a pig -, to the head of the house, and it does not seem possible at the moment to infer client relationships between the owners of these few cattle. On the other hand, it is possible to extrapolate with some degree of precision the data on the location of those who entrust their cattle to the house head: they do not seem to belong to the same territorial groupings90. 19^th^-century data also contain only one - albeit very important - indication on the corti. In 1871, a note of the livestock of the company in the Alps of Cravariola organised by the lawyer Guglielmi, owner of the most imposing and richest house in the - by now central - village of Crodo and today the seat of the town hall, specifies that this house uses the "Court of Crego"91. This doesn't mean that the territorial tensions of the previous two centuries between the hamlet of Crego and the villa of Crodo are forgotten: in 1929 Crego will ask to be incorporated in the commune of Premia, which will agree and in exchange will yield a part of its territory to Crodo92.

The change in the local political structure we are hypothesising is not without consequences: it manifests itself on the ritual level. The years of the land surveys themselves coincide with a conspicuous appearance of the hamlets on the ritual level, and in different ways.

On the one hand, the territorial structure by hamlets asserts itself on the ritual level: from the end of the 17^th^ century, "quarters" were appointed for the first time in a proxy to collect parish tithes (Chiesi, 2019)93.

Notarial documentation, for its part, reveals how universal was the practice of hamlets testators to leave as per local tradition an alms of salt to the neighbouring94. From a late document, then, we learn that in Crodo salt alms (extremely common in the eastern Piedmontese Alps) were in fact managed by ritual "quarters"95.

All these indications point to an accentuation of the presence of the hamlet on the ritual level in response to its ousting from the formal presence on the Alpe and its disappearance from the formal organisation of the Crodo terzello. But also on the devotional level, the presence of the Crodo hamlets became more conspicuous: in the 18^th^ century the hamlet of Crego concentrated devotional investments on the oratory of San Rocco, which in the following century took on an original form thanks to the work of a local priest96.

The reaction of the hamlets to the effective creation of the administrative commune in the alpine regions of the Ossola thus shows how the drafting of new land registries unhinged territorial bodies of centuries-old tradition that had allowed the - admittedly quarrelsome - management of the high pastures (Mannori, 2008)97. In this case, the ritual visibility of the hamlets seems to correspond to their political defeat.

4 - Hamlets' commons, opposition to the municipalisation of charity and the foundation of a new commune (Rosazza, Valle Cervo)

Rosazza is a small village in the Cervo Valley (province of Biella) that became an autonomous municipality in 1906, including the hamlets of Beccara and Vittone. Before that date, the hamlet of Rosazza was the protagonist of strong conflicts with the village of Piedicavallo, the chief town of the municipality of the same name. One of the main reasons, although as we shall see, not the only one, concerned the management of common property. Until at least 1906, the commons of Rosazza were included, without explicit division, within those of Piedicavallo and heavily determined their affairs98.

The formation of the municipality of Piedicavallo occurred following the dissolution of the Mandamento di Andorno at the beginning of the 18^th^ century and generated an impressive series of disputes between the settlements that were part of it. In one of these, Piedicavallo claimed that 40 hectares of territory had been taken from it in favour of Campiglia. These were lands located in the valley facing the hamlet of Rosazza but belonging to the hamlet of Mosca (today Valmosca), which served both as pastureland for this hamlet and as passage for the herds and flocks of the Cervo Valley communities towards the Aosta Valley, its pastures and markets. Furthermore, Piedicavallo claims that the division did not proceed in cross-examination with the community itself. Other complaints came from other communities of the former Marchesato d'Andorno, which were not given sufficient pastures and tree leaves for the feeding of their livestock. The reply was that in such cases one must base oneself on the greater goodness and quality situation of the goods and not on their quantity of land, and that in the vicinity of the hamlets of Beccara and Rosazza only three hundred metres of commons were assigned to the community of Piedicavallo, and the same number to Campiglia. Piedicavallo rejected the assignment to Campiglia because it was meant to complete Campiglia's quota and to allow the passage of cattle to the other mountains assigned to them. Piedicavallo claims that the easement to the Marquisate of Andorno (i.e. Campiglia) is groundless since there are other roads leading to the Aosta Valley. As for the woods, it is argued that they are useless woods, even though they are profitable not only for the brushwood, but also for the leaves, and falling trees99.

Figure 11 Piedicavallo and its hamlets. AST, Gran Carta degli Stati di Terraferma, 1852

This division would not be understandable without consideration of the common grazing system of the entire valley and the complex system of reciprocity on which it was based. It contained margins of ambiguity and left room for even bitter conflicts. The grazing system emerges from the conflicts between Piedicavallo - or rather, the hamlet Rosazza - and the contrada Mosche (Valmosca in 19^th^ century military maps, Fig. 11). In a petition, about thirty individuals bearing the surname Mosca retaliate against Piedicavallo and refuse payment of the "mobilia" - i.e. the fee, or cotizzo, on the individual head of cattle - to Piedicavallo, who in turn claims it is paying that fee to Campiglia for grazing on the latter's common property100.

In fact, on 24 October 1729, Piedicavallo obtained an inspection of the Vaj pasture in the Desate region, close to Rosazza, which was disputed by Campiglia and claimed by Piedicavallo. Over this pasture the inhabitants of Mosche, a hamlet of Campiglia, claimed to have rights of access under the pretext that the reason for being able to graze in it has been reserved in their favour on the grounds that the particulars of this hamlet do not have their register at the land register of the said community.