Introductory narrative

Fisheries have long been a vital part of Senegal's economy. Indeed, there is a subgroup within the dominant Wolof culture—the Lebu (or Lebou; Boulegue 2013)—who reside along the central coast and specialize in fishing. Their historic fishing activities are documented, e.g., in Goffinet (1992), with Anita Conti (1899-1997) detailing selected fishing operations at the time Senegal was still a French colony (Conti, 1957).

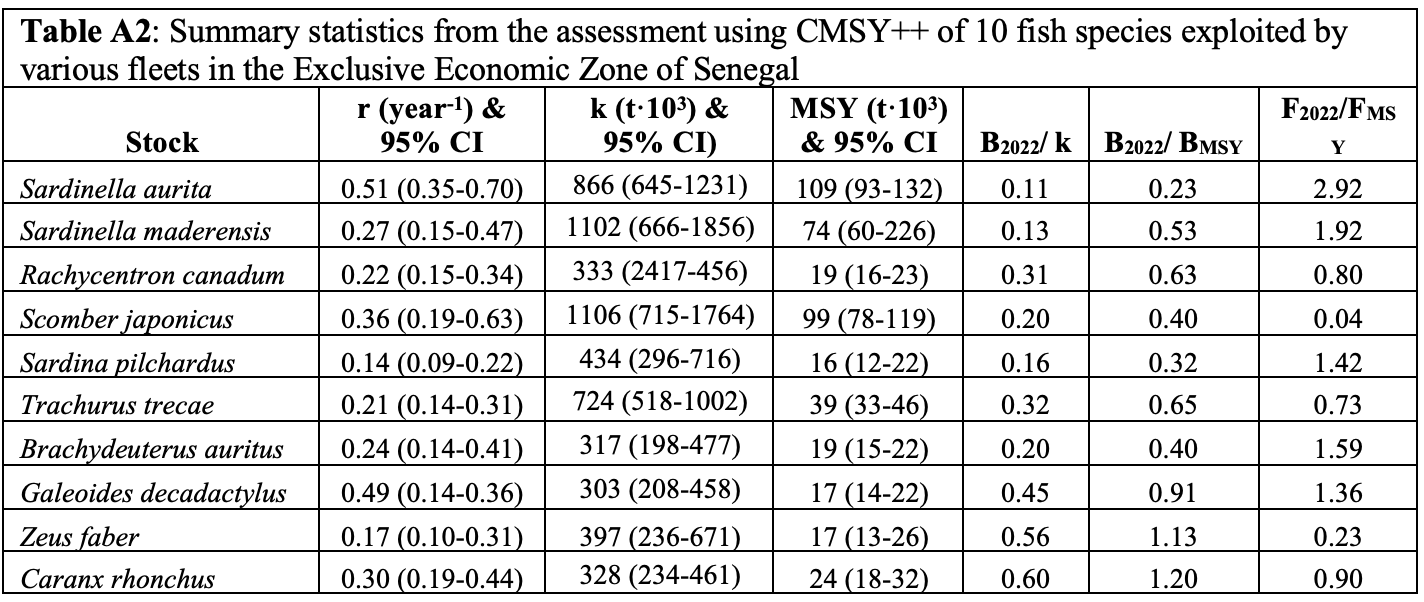

Senegal´s Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ (Figure 1), is extremely rich in fish due to its location within the Canary Current, one of the four major Eastern Boundary Currents (Bograd et al., 2023) or upwelling areas, where coastal winds cause deep, nutrient-rich water to rise to the surface (Bakun, 1990). The upwelled water then supports intense phytoplankton production, which in turn supports a diverse ecosystem of small pelagic fish such as sardines and anchovies. These, in turn, support a variety of large predatory fish, marine mammals, and seabirds (see contributions in Cury & Roy, 1991; Longhurst & Pauly, 1987; Pikitch et al., 2014).

Figure 1: The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Senegal (150,000 km2), with the zone in grey jointly managed by Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. The inshore fishing area (red) extends to 50 km or 200 m depth, whichever comes first. Light blue represents the high seas, while dark blue represents the EEZs of other countries.

The Canary Current ecosystem, which extends from Senegal to Mauritania, Morocco, and the Iberian Peninsula, has been well studied (Chavance et al., 2004; Cury and Roy, 1991), even when compared with the other three Eastern Boundary currents: the Benguela Current, extending from southern Angola to Namibia and South Africa, the California Current, extending from the northwestern coast of Mexico to northern California in the US, and the Humboldt Current, extending from southern Chile to Peru and the coast of southern Ecuador (Bakun & Nelson, 1991).

Our analysis of Senegal's marine fisheries catches began in 1950, when the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) initiated the publication of annual marine catch statistics covering the entire world, including the “Afrique-Occidentale française”, which comprised eight now-independent countries, including Senegal.

Initially, these catches were largely local and reflected the activity of Senegalese artisanal fishers using sailing or paddled canoes, later motorized, locally known as ‘pirogues.’ Gradually, foreign vessels began to appear, mainly from Europe, whose fisheries resources had begun to decline following the respite experienced during the Second World War (Alder & Sumaila 2004).

In 1980, Senegal unilaterally declared an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ; Figure 1), which gained widespread acceptance following the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982. Senegal then attempted to ‘develop’ its fisheries. However, successive national development projects aimed at replacing a wide range of artisanal fishing with semi-industrial and industrial models imported from other regions failed, as documented by several authors (Sall, 2021; Samba & Chaveau, 1990; Sall & Nauen, 2017; Sall & Sow, 2025).

In Senegal, the open-planked fishing boats, or pirogues, are traditionally operated by family enterprises, mostly grounded in Nyominka, Lebou, and Guet Ndarian communities, with bases in the Sine Saloum, the wider Cap Vert (Dakar) peninsula area (with the so-called northern and southern coast lines, called respectively Petite and Grande Côte), and in the area of St. Louis near the border with Mauritania, respectively. These enterprises played a significant role in initially supplying high-value demersal fish species for both domestic consumption and export. As the same species were also targeted by industrial vessels, both flagged to Senegal and foreign countries under fishing agreements, such as those with Europe, their abundance and catches declined, as will be detailed further below.

The strain on Senegal´s fisheries resources, which began to be felt in the 1990s, was due not only to foreign industrial vessels, but also to the expansion of the artisanal fleets and their progressive modernization through the introduction of nylon nets, outboard engines, ice boxes for high value species, and deployment of larger pirogues with crews of 20 fishers or more who used purse seines to catch small pelagic fishes (or ‘small pelagics’) such as Madeiran sardinella (Sardinella maderensis) and round sardinella (S. aurita). Other high-value species gradually became targeted for export, notably shrimps, cephalopods, and tuna.

The fishers in Guet Ndar gradually began catching small pelagics with large encircling nets, moving seasonally following the schools in the upwelling areas of the Canary Current, specifically from southern Senegal to northern Mauritania (Barry-Gérard, 1994; Samb & Pauly, 2000). Given the increasing fishing pressure in Senegalese waters by both industrial vessels with very high catching capacity and the growing number and size of artisanal pirogues, the activities of Senegalese artisanal fishers began to ‘spill over’ into neighboring countries, particularly into Mauritania, The Gambia, Guinea Bissau, and Guinea (Belhabib et al., 2014a,b).

Awareness about the pressure on Senegal’s fisheries resources gradually grew, including among the authorities, such that the notion of a ‘biological rest’ period was introduced into the protocol for renewing the fishing agreement between Senegal and the European Union (EU) for the period 1997-2001. However, this was insufficient to halt the decline in net incomes in the face of increasing costs (Ba et al., 2017).

Attempts to restrict fishing effort in the 1990s, initiated by local communities in Yoff and Kayar for demersal and in Guet Ndar for pelagic fish, aimed to achieve higher sale prices. However, these efforts could not be sustained due to inadequate refrigeration infrastructure, limited marketing experience, and collective actions that were not sufficiently strong (Gaspart & Platteau, 2001). Efforts in Ngaporou to protect its fishery resource base, supported by strong local leadership, an international NGO (WWF), and the local government, held up for a time. Still, they were unable to prevent the incursions of ‘migrant fishers’ who did not share the same objectives.

Indeed, the role and impact of migrant fishers have increased as a result of resource shortages closer to home and demand of national and international markets (e.g., octopus was not originally part of the targets, but became one due to export demand) and migrants are known not to feel bound by local social and technical restrictions. Due to the scale of migration into neighboring countries, Senegal has established fishing agreements with several countries. It has had to repeatedly intervene, e.g., with Mauritania, stopping ‘migrant fishers’ from Guet Ndar from trespassing. The artisanal port built in the country, partially with EU funding, cannot hold the large numbers of pirogues it has. The migrant fishers from Guet Ndar were mostly working under contracts with Mauritanian businesspeople. They also tried several other contractual arrangements, e.g., loading their pirogues onto industrial mother ships for line fishing of valuable demersal fish in Guinea in areas not easily accessible to the pirogues on their own.

The confirmation of oil and gas fields shared between Mauritania and Senegal in 2015 set in motion another negative dynamic that affects wider climate policy, as well as the artisanal fleet based in Guet Ndar, specifically due to the exploitation platforms and connections to land stations making the historically productive shoals in their vicinity inaccessible (Mundus maris, 2024).

The social fallout of excessive pressure on resources was most strongly felt in the unraveling of social cohesion, which had been compensating for the lack of public social services. While part of the rural workforce displaced by the droughts of the 1980s was absorbed — particularly into the purse seine fisheries, which required more hands-on-deck due to fleet expansion — declining economic returns led boat-owning families to reduce their support for crew members, such as housing and food, thereby increasing crew mobility between boats. Moreover, the economic strains were particularly affecting women, especially those in rural areas, who worked under harsh conditions on the landing beaches (Mundus maris, 2018a; see also contributions in Williams et al., 2005).

While women in traditional large fishing families formerly had considerable income and managerial clout for the family business — a situation that went hand in hand with much higher social status than women in agriculture as illustrated by the interview that Aliou Sall conducted with Khady Sarr in Hann in 2018 (Mundus maris, 2018b) — the intense competition for access to shrinking resources undermined their managerial roles drastically. The influx of capital from outside the social structures in the fishing communities is progressively displacing women from managerial roles to those of paupers or fish factory workers, among others. As Sall and Sow (2025) describe, women used to get access to landed fish from their family pirogue with payments for fishers and maintenance of equipment deferred until they had processed and sold the landed fish. With the proceeds, they would also pre-finance the next fishing trip to secure privileged access to the landings. As other investors with deeper pockets entered the market, particularly with the rise of fishmeal factories established by foreign investors, who would pay cash and sometimes offer higher prices initially, the women found it increasingly difficult to keep up with rising costs and a lack of suitable credit facilities.

According to Awa Djigal, Secretary of the Réseau des Femmes dans la Pêche au Sénégal (pers. comm. to C.E. Nauen), women in processing and trading have never been recognized officially, so that they do not have, so far, access to social services or rights, be it for land tenure, as elaborated upon by Sall and Sow (2025) — or even minimal support for access to sanitary facilities in Hann, even though the health impairment and insecurity are well documented (Nauen, 2022). In Senegal and neighboring countries, most remaining high-value fish and invertebrate species are now exported. Marketing is increasingly controlled by Lebanese, Chinese, or South Korean operators, forcing women to buy often frozen, low-quality raw materials. Small pelagics, once widely traded across the Sahel, are now scarce, with much of the supply diverted to fishmeal production — if available at all (Mundus maris, 2018a; Sall, 2018; Sall & Sow, 2025). As climate change altered the distribution of sardinellas and other species, their regional refuge in Casamance — which had supplied low-income consumers not only in Senegal but also in Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali, and beyond — was partially undermined by the construction of a fishmeal plant in a protected area near Kafountine (see below for the devastating impact of fishmeal plants).

The lack of policy support from governments for the men and women involved in small-scale fisheries, combined with the concomitant evolution of urban incomes and changed expectations for hygiene and the general presentation of fish for purchase, was further reducing the scope for women to continue their traditional roles in processing and marketing fish using traditional methods. The ‘boutiques’ and mini-super-markets run by Lebanese or ‘Asians’ in Senegal became more attractive to these urban middle-class consumers than buying fish on the beach or street market in less attractive hygiene and display conditions.

A first wave of irregular emigration associated with the sequalae of the draughts in the 1970s and 1980s and the substantial negative impact on traditional agriculture in the catchment of the Senegal River through industrial scale irrigation schemes documented by Hochet (2000) pushed Senegalese migrants toward the outskirts of Paris, but also to Belgium, Spain and Italy, with some being able to study and acquire professional status. Thanks to the increased availability of cheap modern communication, the links to this Europe-based Senegalese diaspora are close in many families. Thus, unsurprisingly, with the sharpening of the marine governance crisis leading to declining fisheries catches and incomes, emigration has become an option considered by an increasing number of families.

While not openly discussed, sending young men to earn money in Europe was facilitated by the diaspora network and led to the construction of new houses back home, as evident in Kayar and other places. This wave of primarily young men from West African coastal areas (not only from Senegal) made the hazardous trip across to the Canary Islands. However, as Sall and Morand (2008) point out, while experienced captains from the artisanal fishing fleet conducted the migrants across, the fishers were not the majority, but rather the executive supporters. While sporadic interviews with migrants suggest that the erosion of rural livelihoods is a driving force, the cost of the journey often exceeds the means of the poorest. The numerous arrivals and losses of life at sea recently are shedding a fresh light on the complexities between macro-trends, such as drought, overfishing, and climate change, and other factors that play a role, but they provide only a partial explanation. The desire for a better life, the perceived high living standards in Europe, the lack of access to education and other opportunities at home, the political instability, a lack of security, and the pull factors of the diaspora are additional drivers.

The cost reduction in communication and the rise of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) engaged in nature protection were a source of hope for greater cooperation on common goods and more justice, thanks to the ability to hear voices beyond the established political and economic elites (Nauen, 1999). Yet, two decades of ‘protecting the ocean’ turns out to have been simplistic, as powerful foundations channel enormous amounts of funding into big international NGOs while often neglecting the required trust between artisanal fishers, Indigenous Peoples, small-scale farmers and local NGOs who should have been their natural allies (Nauen, 2024).

Underneath the issue of natural resource stewardship lurks the issue of social justice and trust in more profound ways than initially meets the eye (Nauen, 2023). The concept of ‘shifting baselines’ (Pauly, 1995) provides an extra pointer: while the older generation can remember a sea teeming with life and abundant resources, the current generation and the young entrants in the fishery see only the difficulties, yet will try their luck if they don’t have alternatives. A recent study with Spanish artisanal fishers illustrated the extent of being ‘locked in’: Salgueiro-Otero et al. (2022) showed that Galician fishers within a tightly knit group would accept substantial income losses before considering change, while women with broader networks and access to a greater diversity of information sources would move much earlier. Similar results were reported from the Philippines by Bailey (1982).

Thus, the question can be asked: can this vicious cycle be broken, resources restored, livelihoods consolidated, lives saved? In other words, can we shift from what has been described as Vanishing Fish (Pauly, 2019c) to Infinity Fish (Sumaila, 2021) — that is, halt overfishing and habitat destruction, and rebuild fish stocks so they can sustainably provide food and nutritional security for generations to come? The simple answer is yes. However, it is not easy to implement when powerful structural forces and poor policies continue to shower harmful subsidies on industrial fishing and fossil industries (Dempsey et al., 2020), and maintain unjust trade relations (Skerritt et al., 2023). While many international agreements are underpinned by generally accepted principles that have been hard-fought after years of negotiations, the implementation gap tends to be large and insufficiently bridged.

Several initiatives are underway that can offer pathways to address this gap. To mention a few, NGOs are coming together under the umbrella of the ‘Rise Up for the Ocean’ initiative (https://riseupfortheocean.org/) that makes an explicit effort to create space for artisanal fishers, both men and women, to speak out for themselves in favor of prosperous coastal communities and support their demand for marine spatial planning and infrastructure developments made only with their prior informed consent. Rise Up for the Ocean supports the amplification of messages from the directly affected people. It does not attempt to substitute itself for them; rather, it supports strengthening the capacity of the people and their leaders directly.

In a similar vein, Mundus maris (https://www.mundusmaris.org/) has launched, together with a cross section of women and men in artisanal fisheries in Senegal, a Small-Scale Fisheries Academy with the explicit aim to support capacity strengthening for the operationalization of the ‘Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries’ (SSF) in the context of food security and poverty eradication. The SSF Guidelines were adopted by the Committee on Fisheries (COFI) of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2014, following several years of extensive bottom-up deliberations (FAO, 2015). While the principles are widely accepted and inform national action plans in some countries, including Senegal, the practical implementation meets significant challenges. The initial training workshops offered by the SSF Academy, before the COVID pandemic, were based on respectful and inclusive dialogue formats in a safe space, tailored to put participants at ease and enable them to develop individual and collective plans for improving their lives. The workshops were conducted primarily in the local language and utilized drawings rather than written materials to convey concepts to all participants, including those without formal education (Nauen & Arraes-Treffner, 2021, 2022). Training resumed with other support after the pandemic, driven by one of the early adopters in Yoff, and has generated good results against the trend elsewhere.

Participatory approaches hold much promise for overcoming the divides that prevent the implementation of many agreements, although it would be naive to think they are self-runners in contexts of substantial power differences and opposing interests. Nonetheless, the possibility of reaching consensus in international settings, given initial positions that are often far apart, is testimony to the fact that dialogues with explicit space for the expression of different voices hold promise for more balanced solutions than would be the case when only a few impose their will. The international arena demonstrates that these processes can be lengthy and resource-intensive. At smaller scales, it is often easier to move toward agreed-upon objectives.

In Senegal, the newly elected government in 2024 is seeking increased interaction with various interest groups as it explores ways to address the crisis in fisheries and establish the legitimacy of the institutions established by the previous government and its international development donors. The jury is still out on whether this will lead to rebuilding marine resources and a better balance between domestic livelihoods and the imperatives of external debt service. A useful step beyond consultations with small-scale fishery representatives would be to invest in greater access to data and information about all facets of the sector, enabling more comprehensive analyses and advice. Greater transparency, combined with accountability, would be a way to rebuild legitimacy. The recent seizure of a pirogue load of illegally caught juvenile fish signals a willingness to improve resource protection and law enforcement. The ensuing attack on the Fisheries Control Post in Joal suggests, conversely, that rule enforcement in a socially and economically fragile environment (Ba et al., 2017) is not trivial (Diébakhaté, 2025).

This final point, about greater transparency, is the motivation behind this article, which aims to show that (i) Senegal’s fisheries resources are overexploited, (ii) the overexploitation began very early, when the local artisanal fisheries were happily expanding to maintain their catch in the face of increasing competition from foreign ‘Distant-Water Fleets’ (DWF), and (iii) how the ‘Western press’ explained a migration crisis that has now led to thousands of drowned or otherwise dead would-be migrants.

Materials and Methods

Rather than the free form of our introductory narrative, the following parts of this contribution are structured more like in articles in natural science journals, with Materials and Methods, and Results and Discussions sections segmented, as required for very different topics, to provide more explicit definitions of technical terms such that it hopefully remains readable by colleagues without a background in fisheries research.

Catch reconstruction

The world’s maritime countries are supposed to send annual catch statistics of their fishing fleets to the FAO, and almost all comply. However, these catch statistics are usually incomplete and misleading, as they mainly cover the industrial fishing sector. The catch of artisanal fishing sectors is often underreported, if at all. The recreational (or sport fishing) and subsistence fishing sectors are generally overlooked (Pauly & Zeller, 2016a), as are discarded fish, which in the 21st century account for approximately 10% of the world’s marine fisheries catch (Zeller et al., 2018).

Countries owning DWFs usually report the location of their catches (when they do report them) to Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), generally by ‘squares’ with sides of 5- or 10-degree latitude and longitude, and without references to EEZ (Coulter et al. 2019). FAO then allocates these data to its 19 giant FAO Statistical Areas, without indicating whether these catches came from the High Seas (areas beyond national jurisdictions) or the EEZ of various countries. If the catch came from the EEZ of multiple countries, in principle, they could only have operated within the framework of an access agreement with each country in whose EEZ they had fished (Le Manach, 2014; Le Manach et al., 2013). Unfortunately, many DWF fish illegally, without access agreements, in the EEZ of countries that lack the technical capacity to monitor their own EEZ or otherwise prevent such incursions (Sumaila 2018; Sumaila et al., 2020).

In the 2010s, the Sea Around Us initiative at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, developed an approach now known as ‘catch reconstruction’ to address the various issues associated with the aforementioned deficiencies. The principle underlying catch reconstructions is that any social activity, especially one related to larger-scale deployment of technology and that is deeply connected to markets, will throw a ‘shadow’ on the society in which it is embedded (Pauly, 1998) in the form of employment provided, fuel used, fish supplied to local markets, surveys of fish consumption, etc. Thus, the situation does not exist where there are ‘no data’ as claimed by many. Rather, while the available data may be unconventional, they can replace the “zero” catches typically used in poorly documented fisheries.

In the case of Senegal, the reconstruction of its marine catch was facilitated by the fact that its fisheries statistical system was in part developed with the assistance of French scientists from ORSTOM and, later, IRD who assisted the Senegalese government in establishing a detailed monitoring system for its artisanal (pirogue) fisheries, which, for a time, put Senegal among the countries with the best fishery statistical system in the Global South (Alder et al., 2010; but see Belhabib et al., 2015).

Assigning distant-water fleets' reported catch to the EEZs of coastal countries involves information on access agreements, which are well documented in the case of EU countries (see Le Manach, 2014; European Commission, 2014), while others discussed documents issued by entities, notably technical organizations of the United Nations, e.g., UNCTAD (2024).

Other countries, including China, have access agreements between fleet owners and governments that are not publicly available. Some countries, such as Russia, resort to illegal fishing, who, for example, has an access agreement with Mauritania but did not have one with Senegal when, in January 2013, one of its trawlers, the ‘Oleg Naydenov,’ was caught during one of its regular incursions into the Senegalese EEZ (Reuters, 2014; MariTimesCrimes, 2024).

However, assigning DWF catches to EEZs has become easier since the emergence of Global Fishing Watch (GFW) in the mid-2010s (Kroodsma et al., 2018). The GFW documents the position of DWF vessels by tracking the satellite signals of their Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). This monitoring mechanism identifies where a country’s vessels are operating. If a vessel has switched off its AIS, it can be assumed that they are fishing illegally.

Combining access agreements, GFW data, and the reported catch composition by species generally allows identifying where the catch was taken. Thus, given the distribution range of each species, which is provided from FishBase (www.fishbase.org), it was possible to reconstruct the catch of DWF in each EEZ of the world, including Senegal (see Pauly & Zeller, 2016b).

The reconstruction was complemented by various inferences, allowing the improvement of the artisanal catch statistics from Senegal, notably by accounting for fish taken from the EEZ of Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and the Gambia and small but economically and nutritionally important recreational catches by foreign tourists and mostly female subsistence fishers, respectively (Belhabib et al., 2013, 2014a 2014b; Lopez-Ahedo, 2025).

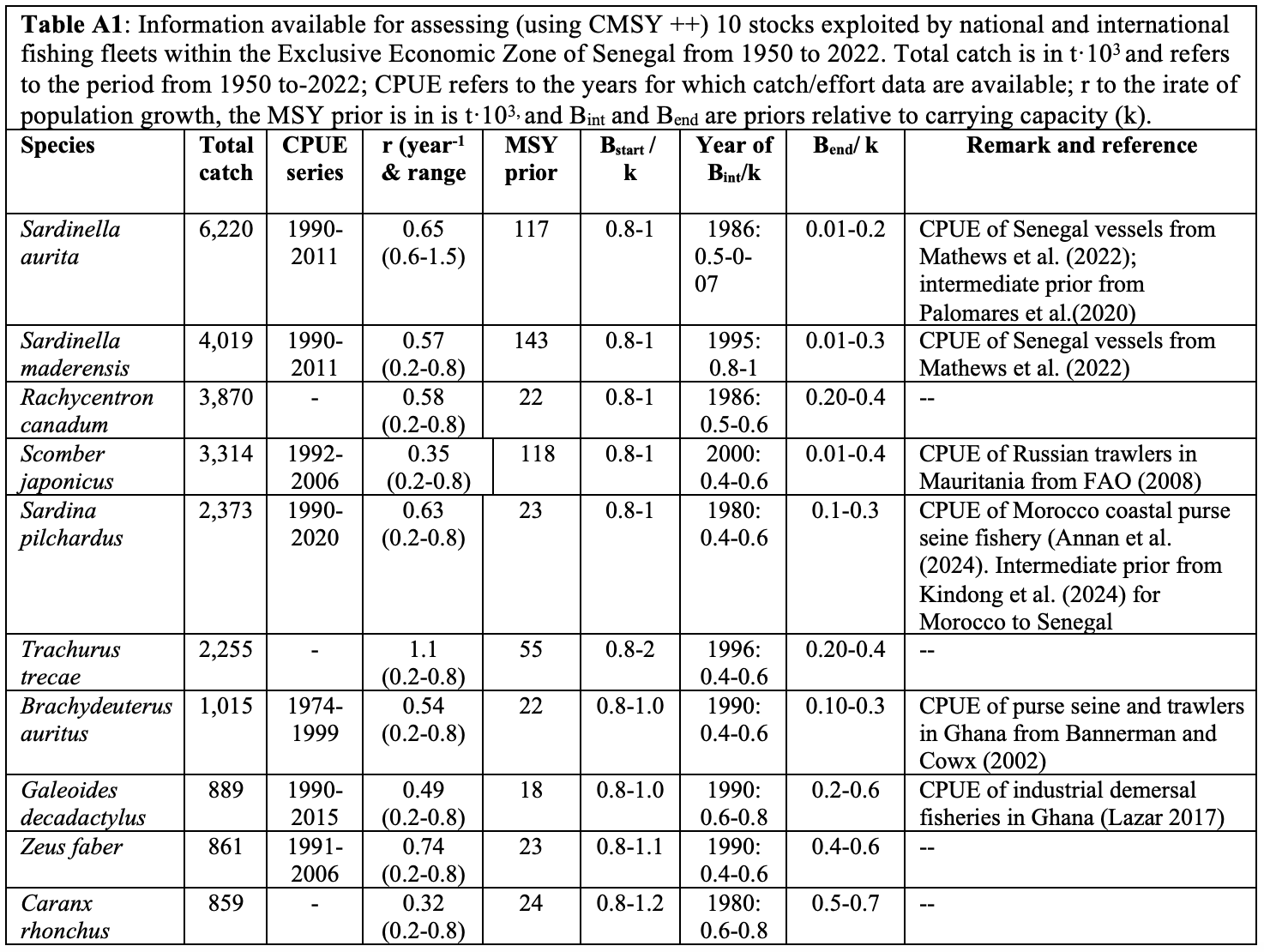

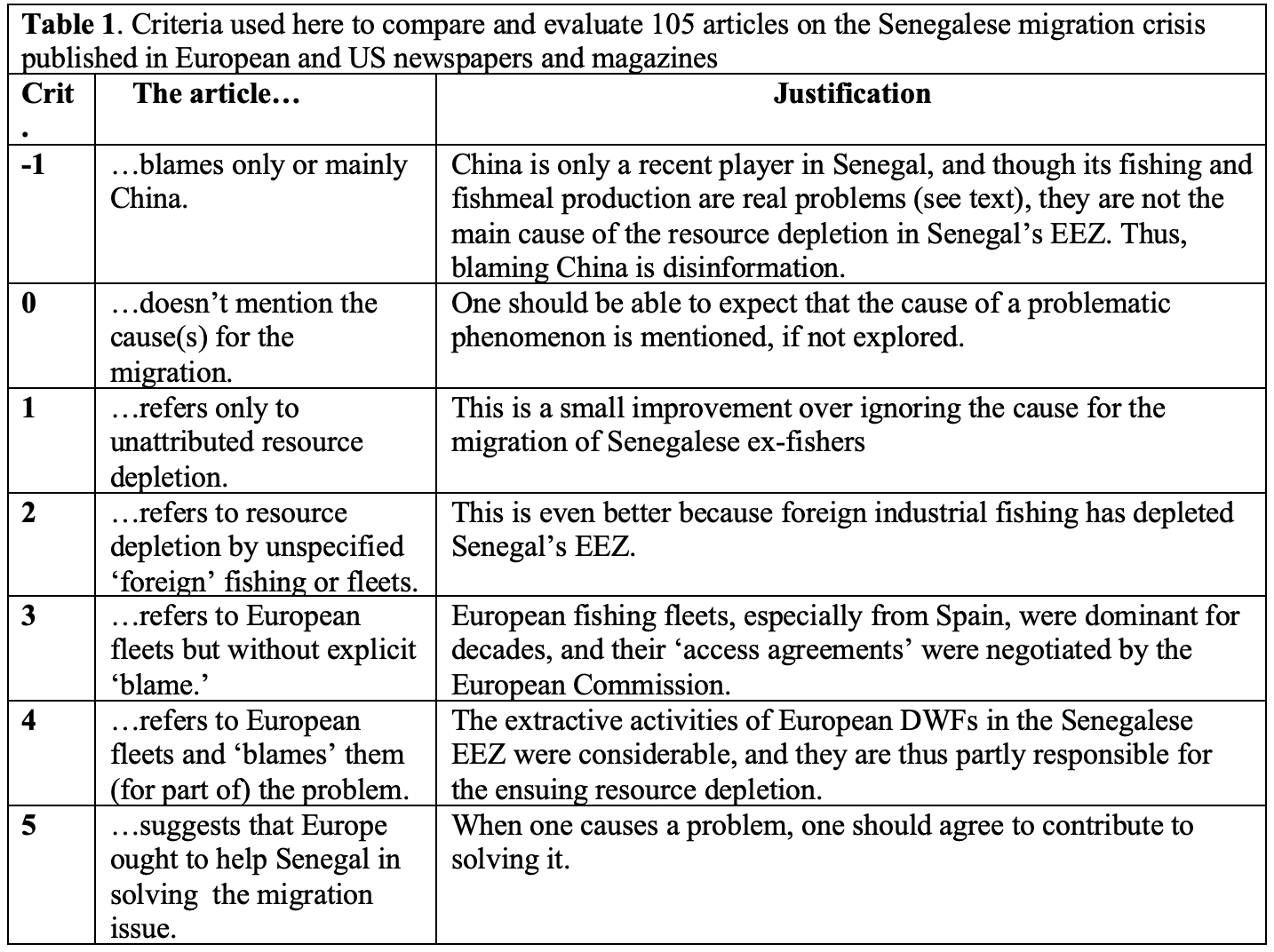

Stock assessments

To manage fisheries effectively, the exploited fish stocks or populations must be accurately assessed. These assessments enable managers to adjust the level of fishing effort and generate a fishing mortality that, for example, achieves Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) (Pauly & Froese, 2020).

A stock assessment is used when we know the value of F relative to the fishing mortality, which generates MSY (or FMSY), that is, F/FMSY. Such assessments involve estimating the biomass (the weight of a fish population in the water at a given time), which should ideally be at BMSY, which is half of the unexploited biomass or B0. Thus, B/BMSY is smaller than one.

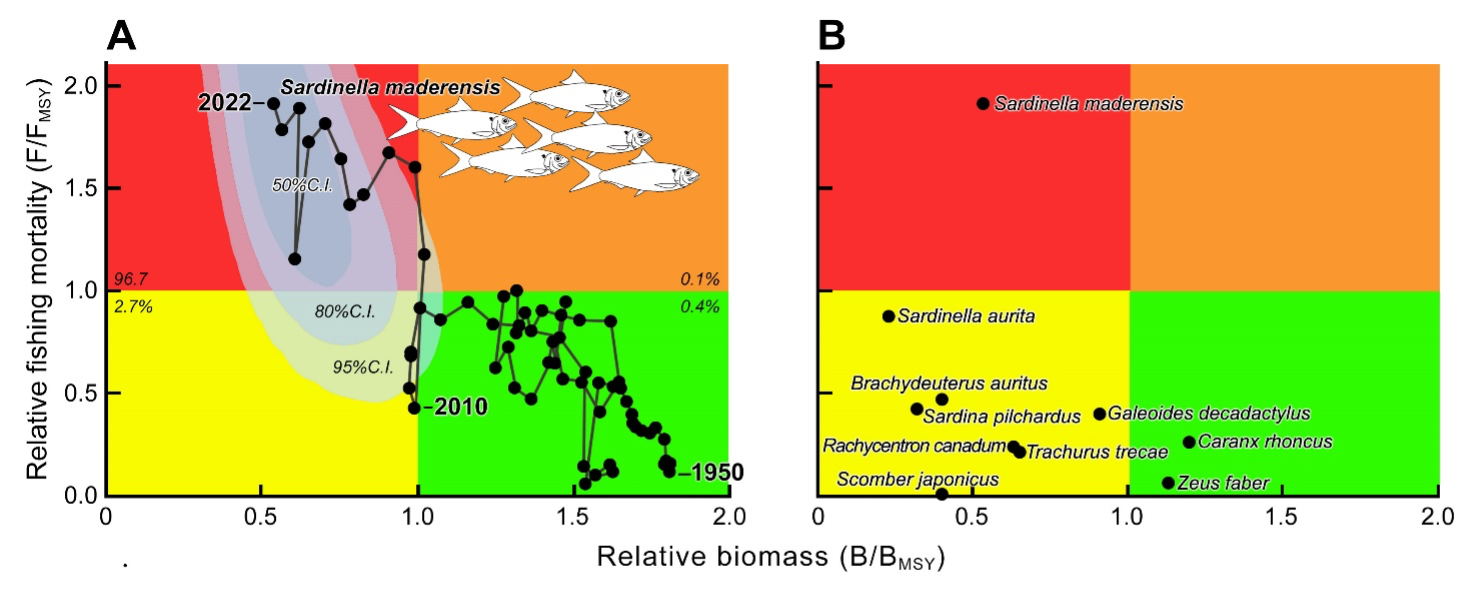

CMSY++ (Froese et al., 2023) is a method to estimate annual biomass values given a time series of catches and some supplementary information. It was applied here to the 10 most representative species in fisheries catches in Senegal, with the results shown in so-called ‘Kobe Plots,’ whose ordinate is F/FMSY and whose abscissa is B/BMSY.

In such plots, the current location of a stock is indicative of its status, with the green surface on the right (with B/BMSY > 1; F/FMSY < 1) being where the stocks were initially located, with most ending in the red surface on the left, with B/BMSY < 1 and F/FMSY > 1 (Figure 4).

Climate change effects

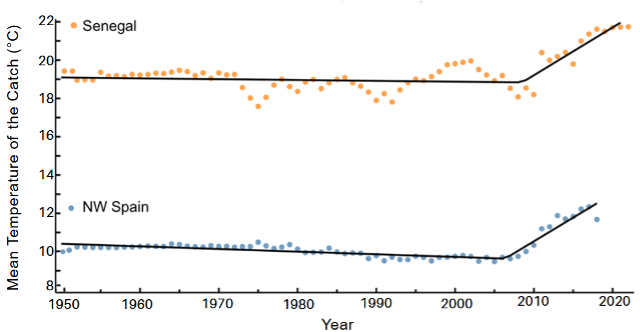

Climate change strongly affects the oceans through warming and deoxygenation, which have a powerful impact on animals that breathe water, as fish do (Pauly, 2019a). One of these effects is the gradual poleward shift in the distribution of fish (Cheung et al., 2009), which can be demonstrated via the Mean Temperature of the Catch, or MTC (Cheung et al., 2013).

MTC is based on a fish's preferred water temperature, which can be taken as the average temperature at the center of their distribution. This temperature is relatively stable—it doesn’t change over centuries, though it may over millennia.

To estimate the MTC in a given year, we only need the preferred temperature of the species occurring in the catch from an EEZ to compute its average over all species weighted by their abundance. Over the years, if the composition of the catch is changed by increasing catches of lower-latitude species, this will increase the MTC (see, e.g., Dimarchopoulou et al., 2022).

For comparison, the Mean Temperature of the Catch (MTC) was calculated for Senegal and northwest Spain using catch data reconstructed by Lopez-Ahedo (2025).

Beyond ecological shifts, climate change has significant economic and equity implications for marine fisheries. Rising ocean temperatures, acidification, and deoxygenation alter the productivity and geographic distribution of fish stocks, which in turn disrupt the economic benefits derived from fisheries, particularly for countries in the tropics, such as Senegal (Lam et al., 2016, 2020; Sumaila et al., 2011).

Sumaila et al. (2019b) show that developing countries—particularly those in Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific — face the greatest losses in fisheries revenue due to warming oceans, as fish migrate poleward and out of their EEZs. This redistribution of fish biomass leads to widening economic inequities between countries that are gaining fish (e.g., higher-latitude nations) and those that are losing them (e.g., equatorial and tropical countries such as Senegal).

Moreover, within countries, climate-driven changes can deepen distributional injustices. Small-scale fishers, who often lack the mobility, capital, and political voice of industrial fleets, are more vulnerable to stock declines and displacement. Sumaila et al. (2019b) stress that without inclusive adaptation policies, climate change could erode livelihoods, increase poverty, and intensify food insecurity in coastal communities.

The discounting of future impacts also plays a critical role. Sumaila (2021) argues that using high discount rates in fisheries management underestimates the long-term losses from climate change and weakens the case for rebuilding efforts. This work builds on the concept of intergenerational discounting in economic valuation, emphasizing the importance of preserving fisheries resources not just for current, but also for future generations.

To confront these challenges, Sumaila et al. (2019b) advocate for climate-resilient fisheries policies, including stopping overfishing, rebuilding depleted stocks, and phasing out harmful subsidies, especially those provided by DWF nations (Skerritt et al., 2023). These measures can enhance adaptive capacity while promoting a more equitable and sustainable ocean economy.

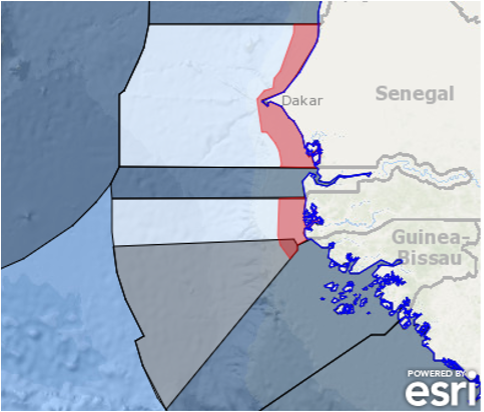

Assessing media coverage

Even though our introductory narrative presented a complex causal nexus for the out-migration of Senegalese citizens toward Europe, it is well attested that fisheries resource depletion contributed massively to the impoverishment of fisher communities in Senegal. Thus, DWFs operating in Senegal, including those from the EU, are, at least in part, responsible for this out-migration to Europe, whose effects are generally misunderstood by the general public, leading to various anti-immigration policies and the multiple human rights abuses that are the unavoidable consequences of such policies.

To assess the degree to which the public in the EU and allied countries is informed by the press about these issues, over 100 articles from newspapers and magazines from major countries were scored as to the insight(s) — if any — they provided into this crisis. Table 1 presents the criteria used to rank the articles, which range from 0 (no reason given for the migration) to 5 (the reason is, among others, that the EU contributes to the depletion of fish off Senegal, and this calls for reparation). A score of -1 is assigned to articles that primarily or solely blame China (see, e.g., Clover, 2020). For about a decade, the Chinese distant-water fleet has operated within Senegal’s EEZ, and newly opened Chinese-owned fishmeal plants now divert food fish away from direct human consumption. However, their presence in Senegal is relatively recent and is not the sole cause of the migration crisis; this topic is discussed further below.

Results

The state of the marine fisheries of Senegal

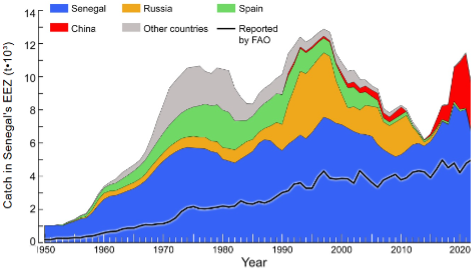

Figure 2 presents a reconstruction of the catch of marine fisheries in Senegal by country, smoothed by a 3-year running average to allow trends to become visible by suppressing some inter-annual variability.

Figure 2: Catches of various countries in the Senegalese EEZ, smoothed by a running average (over three years) to make trends more visible. The ‘Other countries’ category includes France, Italy, and other E.U. countries, but all with catches much smaller than Spain’s.

As can be seen, the DWF catch accounts for roughly half of the catch in the Senegalese EEZ, which is higher than the 40% average for Africa as a whole. Moreover, a large fraction of the industrial catch attributed to Senegal is only nominally owed by Senegalese enterprises. However, this topic is not pursued here. The black line shows the catch that Senegal reports to the FAO.

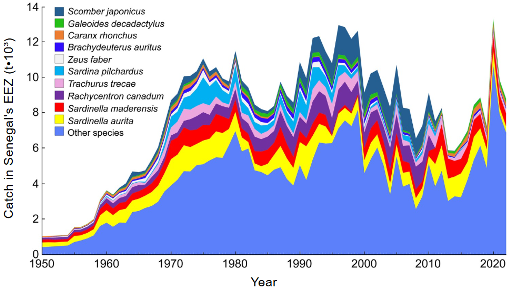

Figure 3 presents the same catch as Figure 2 for the 10 most important fish species (+ others) without smoothing. There is much inter-annual variability, which adds to the uncertainty in stock assessments.

Figure 3: Taxonomic composition of catches in the Senegalese EEZ.

Figure 4 presents two Kobe plots: the one on the left presents the trajectory of the Madeiran sardinella (Sardinella maderensis) from underfished (in the 1950s) to overfished (from the 2010s), with the dots representing the years from 1950 to 2022; and on the right the 10 species from Figure 2, of which most have low to very low biomass, in line with results obtained for NW Africa as a whole (Christensen et al., 2004). However, there is much uncertainty about their precise position on the Kobe plots due in part to inter-annual variability. Details on the methods and priors used for these assessments can be found in Appendix Tables A1 and A2.

Figure 4. Kobe plots summarizing the status of fish populations exploited by unmanaged fisheries, which usually devolve from the green (abundant biomass, low fishing mortality) to the red quadrant (low biomass, excessive fishing mortality). A: Trajectory of the Madeiran sardinella, from 1950 (lower right corner) to 2022 (upper left corner) with each intermediate dot representing a year. Sardinella maderensis accounts for 8% of the total catch in Senegal, with 4.5 million metric tons caught between 1950 and 2022. B: Low biomass position (in 2022) of the top 10 species representing 45% of the total catch of Senegal for the period 1950-2022.

The Effect of Ocean Warming

Figure 5 compares the Mean Temperature of the Catch (MTC) from the Senegalese EEZ with the MTC of Northwest Spain. Both trend lines show the expected ‘hockey stick’ pattern (Dimarchopoulou et al., 2022; Kangur et al., 2022; Mann, 2012), indicating that the fisheries, since 2005-2010, in Senegal and Northwest Spain, caught increasing amounts of newly migrated fish from lower latitudes, indicating the waters in these lower latitudes are becoming too warm for the species in question to thrive.

The declining trend preceding the rapid increase from the mid-2000s is attributed to industrial fishing’s tendency to fish deeper with time, as shallow-water species are gradually depleted. Morato et al. (2006) documented this, and Dimarchopoulou et al. (2022) discussed its effect on MTC.

Figure 5: Mean Temperature of the Catch from 1950-2022 in Senegal and NW Spain.

Assessing media coverage

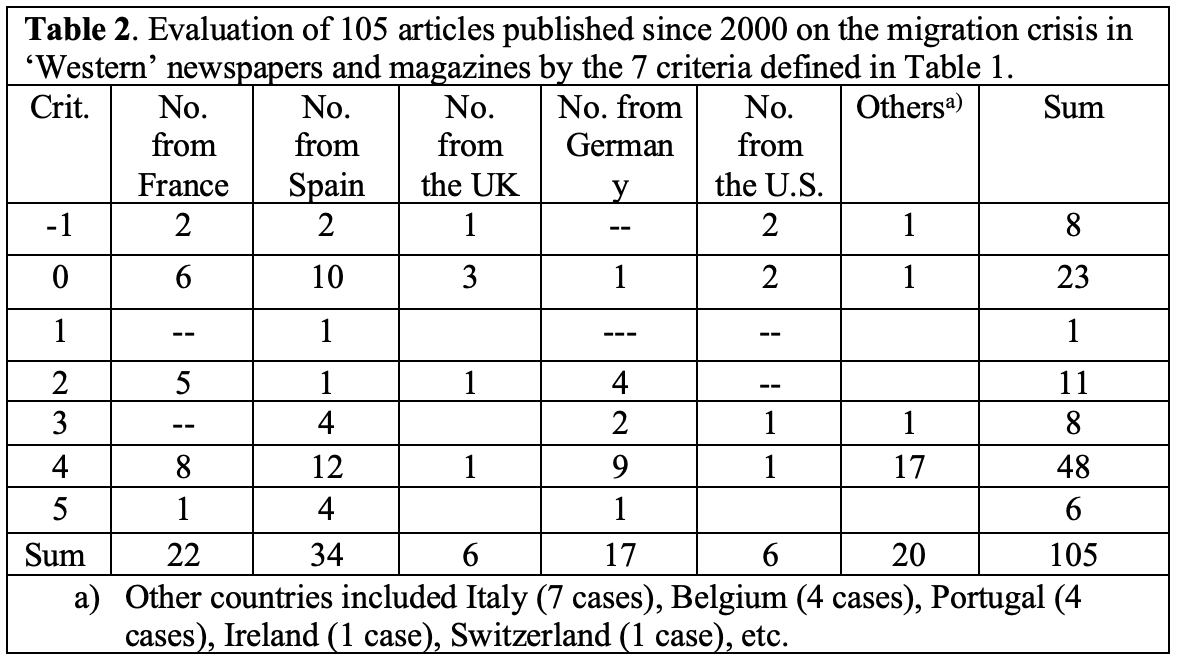

Table 2 summarizes the ‘scoring’ of newspaper and magazine articles on the Senegalese out-migration in the ‘Western’ press since 2000.

As can be seen, the majority of accounts (59%) met criteria 3-5, i.e., they reported on the EU’s DWF operating in Senegal and considered this operation to have contributed to out-migration from Senegal.

Discussion

The issue of access agreements

The massive presence of DWF in the waters of Northwest Africa is explained by four factors: (i) the abundance of marine life in the Canaries Current, alluded to previously, (ii) the depletion of fish stocks in the home waters of the DWF, i.e., in Western and Eastern Europe and in East Asia, (iii) the existence of a world market ravenous for seafood, and (iv) the need of Northwest African countries of the foreign currency provided by so-called access agreements, combined with a limited ability to resist economically and politically strong countries requiring access to their EEZ.

These ‘agreements’ are, in effect, contracts between private companies, countries or entities such as the EU and the government of a country within the EEZ of which a DWF desires to operate, usually for a fee ranging from 4 to 8% of the ex-vessel value of the catch (Belhabib et al., 2015). (Note, however, that EU access agreements do not generally involve a ‘quota,’ i.e., a certain quantity of fish that can be legally taken, but defines a time during which a given number of vessels may operate for a given number of days or months in the EEZ in question …which is the reason why an Irish shipyard built one of the largest fishing vessels in the world, the 140 m ‘Atlantic Dawn,’ now known as ‘Annelies Ilena’).

Since the end of the 1970s, the EU has formalized and developed its Member States’ longstanding and significant presence in the waters of developing coastal States through fishing access agreements that are publicly available, and whose evolution can thus be studied (Le Manach, 2014; Le Manach et al., 2013). The agreement with Senegal was the first one to be implemented in June 1979. The scope of this agreement has evolved significantly over time, from a mix of purse seiners and canners targeting tuna and demersal trawlers targeting bottom-dwelling species such as hake, to essentially tuna purse seiners in recent years. This reduction in fishing opportunities to target demersal species has also resulted in a reduced financial income for Senegal — composed of the ‘access fee’ and ‘sectorial aid’ borne by the EU, as well as the ‘fishing cost’ borne by the industry (Le Manach et al., 2013) — from a peak of close to 45,000 EUR/day (i.e., up to 90,000 EUR/day when adjusted for inflation) in the 1990s and 2000s, to slightly less than 5,000 EUR/day in the most recent period covered by the agreement (Anon, 2025).

In 2024, Senegal published a list of fishing vessels authorized to fish in the country’s EEZ, in which there were 17 tuna purse seiners and canners from Spain and France, along with 132 Senegal-flagged vessels, whose names were most often conspicuously Chinese or Spanish (Anon, 2024). From this list, two Spanish bottom trawlers (targeting deep-sea hake) seem to be missing — CURBEIRO (32 meters in length) and SANTO DO MAR (49.9 m) — although the EU listed them as ‘authorized vessels,’ and appear to have fished in the Senegalese EEZ in 2024 (GFW 2025).

Regarding their fishing access agreement, Senegal and the EU have a complex relationship, one that is rooted in the violent colonial past between France and Senegal. The agreement was shut down in mid-2006, under the presidency of Abdoulaye Wade. It remained inactive until a new Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreement (SFPA), complete with a renewable five-year protocol, was agreed upon in late 2014 (European Commission, 2014), under President Macky Sall. Although President Wade’s decision to denounce the agreement was advertised as a gesture to protect Senegal’s overexploited fish stocks and the need to prioritize local small-scale fishers, the decision was also politically motivated, appealing to nationalist sentiments and the influential fishing communities that form a significant voter base (Poteete, 2018). In fact, the new agreement negotiated under President Sall in 2014 faced strong opposition from local fishers and environmental groups, who argued that the presence of foreign fleets would exacerbate resource depletion and further marginalize artisanal fisheries. The situation is still unclear, as the agreement has now been inactive since late 2024 when negotiators failed to conclude a new protocol, with both sides claiming that it was their choice (Delegation of the European Union to Senegal, 2024; Ministère des Pêches et des infrastructures maritimes et portuaires, 2024). It remains unknown whether it will remain idle, or be renewed, or be denounced again, as it was the case in 2006. Indeed, the 2024 presidential election has further complicated the socio-political landscape and left an uncertain policy environment regarding all fishing arrangements between Senegal and countries with DWFs that operate in Senegal. Tensions have grown between rural coastal communities that rely on artisanal fishing and urban elites who benefit from foreign investments, including those in the fisheries sector (Philippe, 2023).

The ‘China’ issue

The Sea Around Us initiative, of which this is a contribution, engaged repeatedly with the issues of Chinese DWF: once because FAO asked us to examine exaggerated reports of overall Chinese marine catches (Watson & Pauly, 2001), and at two different times to assess the impact of the Chinese DWF for the Fisheries Committee of the European Parliament (Pauly et al., 2012, 2014, 2022).

China’s DWF only began to operate in 1985, largely assisting (through subsidies) its coastal fleet, which, like EU fleets in Europe, had devastated their home waters to fish in the coastal waters of other countries. In this, and other aspects of their operations, they resemble European DWFs but with two important differences (i) China’s DWFs are very big, and (ii) they have very low operating costs (many of their vessels are true ‘rust buckets’) and are even more heavily subsidized than EU vessels. This means that they can operate where EU vessels don’t, despite the subsidies they receive, and can ‘finish off’ the resource depletion by EU and Russian vessels.

As bad as it is, this is not the most problematic aspect of China’s fisheries policy in NW Africa. Rather, it is the opening of a multitude of fishmeal (and fish oil) plants in that region (Shea et al., 2025), which divert sardinella and other small pelagic fishes such as bonga (Ethmalosa fimbriata) from direct human consumption, and export the fishmeal and fish oil to support aquaculture in China, which now consumes 60% of their world production (Pauly et al., 2022), with Norway and its salmon consuming much of the rest. The result of this, combined with the general scarcity of fish, is that thousands of women previously engaged in the sun drying or smoking of fish for transport to the protein-deficient interior of the country have ceased to have fish to process and the average annual fish consumption in Senegal has declined from 29 kg per person in 2008 to 14 kg in 2022 (Bara & Pierre, 2024).

Still, it is disinformation to write, as, e.g., Clover (2020) did, that “China’s fishermen are impoverishing Africa.” This is a job that started decades ago and involved multiple actors, many of them in Europe, toward which many of the victims of this tragedy are now trying to flee.

The role of the Western press

Contrary to some expectations, and various statements in the Senegalese press, we found that a majority of the 105 newspaper and magazine articles we ‘scored’ for their coverage of a major cause for the migration from Senegal to Europe did meet criteria 3-5 in Table 1 (see Table 2), i.e., they did mention that European DWF were involved in depletion of fisheries resources in Senegal’s EEZ. 46% of these articles blamed European vessels for this depletion (criterion #4), although only 6 of 105 articles suggested that Europe should contribute to solving the problem created, in part, by European DWF.

We abstain from presenting further analysis here of the data in Table 2, for example, by time, country, and/or language. Instead, we will focus on the chasm separating current EU fisheries policies from policies that would address the issues of which, as Table 2 suggests, many policymakers are aware.

One of the fisheries policies that contributes most to the issues mentioned above is the massive subsidization of European DWFs (Sumaila et al., 2019a). Subsidizing fishing vessels enables them to maintain their pressure on diminished, overfished stocks, whether in EU waters or overseas. Thus, reducing and gradually eliminating subsidies to EU vessels would not only result in an increase in fish populations in the EU and therefore improve fish supply in the EU, but also enable EU negotiators to insist that Russia, China, and other East Asian countries also reduce their subsidization of fishing vessels.

The recent WTO agreement to prohibit subsidies when fish stocks are overfished clearly cannot fulfill its intended purpose, as it fails to identify the entities responsible for determining whether fish stocks in a given area are overfished. Moreover, its footnote 2 explicitly excludes fishing access agreements from discussion about subsidies, by stating that “government-to-government payments under fisheries access agreements shall not be deemed to be subsidies within the meaning of this agreement.”

Another element here is the contradiction that emerges when one considers that the EU distributes funds to help associated low- and lower-middle-income countries develop their economies, while simultaneously subsidizing the EU's distant water fleet, whose activities undermine their food supply and livelihoods.

The prospects for fish stock recovery

Given the failure of the 2022 WTO agreement to rein in subsidies to DWF (Alger et al., 2023), and of the Paris Agreement to limit greenhouse gas emission such that the mean global temperature increase does not exceed 1.5 oC (Peters, 2024), it is likely that the fish stock in Senegal EEZ will continue to be overfished. This will result in smaller catches and higher greenhouse gas emissions per tonne of fish caught compared to when there is no overfishing. Furthermore, their decline will be accelerated by global warming, whose effects are now evident (see, e.g., Figure 5). While making some progress to put the Ocean and its health onto the political agenda and coming close to the entering into force of the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ) adopted in 2023, the recent UN Ocean Conference (UNOC3) did not manage to go beyond a non-binding declaration of good intentions which are more likely than not to remain unimplemented. Indeed, an informal poll among government representatives at UNOC3 conducted by one of the member organizations of Rise Up for the Ocean revealed a low willingness to stop funding harmful investments and instead prioritize ‘virtuous’ ones in the immediate aftermath.

The annual greenhouse gas emissions from global fisheries ranged between 178 million tonnes (Parker & Tyedmers, 2014; Parker et al., 2018) and 207 million tonnes (Greer et al., 2019a) in the mid-2010s, representing approximately 0.5% of global emissions. This percentage may seem like a small figure; however, it will grow in importance as the effects of global warming intensify, which is inevitable given the continuous increase in global emissions. Thus, all industrial sectors will be asked or forced to reduce their emissions. The question then becomes: what counterargument could an industry subsidized by governments make, whose size and greenhouse gas emissions could be halved or reduced even further, and still generate larger catches from a healthier marine ecosystem?

Increasing greenhouse gas emissions will also result in increasing challenges to global food production, as is already apparent through rising food and feed prices dominated by what Österblom et al. (2015) called ‘keystone actors’ in marine ecosystems. Thus, the conversion of 4 kg of perfectly edible fish like sardinella into 1 kg of salmon or other carnivorous fish in Norwegian-type aquaculture (Cashion et al., 2017; Majluf et al., 2024) might gradually be perceived as the obscenity that it is, particularly when it is protein and micronutrient-deficient countries of Africa — such as Senegal — that provide the fish that are turned into fishmeal (Hicks et al., 2019; Pauly, 2019b), and the salmon is consumed mainly in Europe and the USA, both with annual per capita fish consumption above the global average of 20.6 kg/year (FAO 2024).

Conclusions

This contribution differs from those usually penned by most of its authors. In the natural sciences, one typically tests hypotheses (H), with the conclusion that there is a convergence of evidence for Hx, and not for Hy and Hz, which then usually settles the discussion. This was not possible here, even if one can conceive of the role of DWFs, the status of fisheries, or the position taken in newspaper and magazine articles as hypotheses. Rather, we have described a complex situation in which powerful actors pursue their different, mutually incompatible interests, while less powerful actors are victimized. We cannot even suggest that this situation will improve, although we fervently hope it will.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks the Paris Institute for Advanced Studies (PIAS) for a fellowship in May 2025, during which most of the elements considered in this contribution were assembled and, as well, thanks Sandra Wade Pauly for her support in Paris and with the writing of this contribution. We also thank Ms. Valentina Ruiz-Leotaud, who identified most of the newspaper and magazine articles ‘scored’ in this study.

Appendices