Acknowledgements:

I owe a deep well of gratitude to many people. To my wife, family and friends for their loving support and belief. To all the team at the IEA Paris for nurturing a very special atmosphere where creative thought flourishes, develops and evolves. Finally, to my Impact colleagues and the 1,800 plus participants associated with this study. Many of us tried, through this work, to make a positive difference to the future of the planet. Only time will tell if it mattered. This is for all of you.

High-level outline

Most of us need little reminding of how difficult it can be to practically apply new ideas, especially formal learning, at work. This field, knowledge Transfer, also has significant theoretical issues. Taken together, these challenges question the fundamentals of an industry that spent US$78 billion, largely uncritically, on corporate leadership programmes during 2023. What has become known as the Transfer Problem has defined much of my professional and academic life.

This article seeks to craft a novel solution to issues of Transfer. It focuses on the largely hidden role of time in the application and use of post-programme commitments. Based on a multi-level process study spanning 18 years (2006 - 2024), it explores how participants (1,875) of a 'successful' double-loop learning programme ('Impact') sought to apply transformative change commitments in the workplace. Highlighting Schon's (1984) distinction between the mountain-top and the swamp, it suggests that the problems of transfer are deeply rooted in how we value knowledges, experience reality and see time.

Weaving the central thread of visibility, the article charts the development, evolution and implementation of a visualisation tool. This tool sought to facilitate temporal recontextualisation while connecting change commitments with the flow of work. The findings were stark. They suggested a steep fall-off in the initial practising of commitments as participants returned to their workplaces (e.g. circa 40% in the first 18 days). Furthermore, the visibility of the post-programme context exposed a complex 'timescape' littered with nuanced dimensions of temporality. Here, norma-temporal practices, the dilemmas of liminality and the interactional expectations of others combined to 'crowd out' the practising of well-intentioned commitments. Overall, this produced a visceral sense of 'temporal shock' that limited the capacity to act. Overcoming 'shock' required drilling to the core of identity-laden, temporally infused practices with the aim of reshaping chrono-normative behaviours. This approach generated significant results and fulfilled a comprehensive range of evaluation criteria. There was, however, a painful sting in the tail. Issues relating to levels of analysis and intervention stalked the study. This dynamic reinforced how, as actors, we play with and are played by temporality, at every level, shaping the legitimacy and sustainability of our actions**.** In April 2024, the full ramifications of this statement drew a line under the study.

What follows is a detailed empirical account of the relationship between temporality and change. The account provides a statement of record that captures the evolving processes of understanding and use, both in and over time. It suggests that the incorporation of temporality changes the way we see formal learning - moving it from a disembodied clinical intervention to a liminal temporal interruption. The story unfolds over 4 periods between 2006-2024. It is based at a multinational energy company ('Forum') facing transformative change as it seeks to navigate the emerging landscape of energy transition. Believed to be one of the longest, largest and most comprehensive studies of its kind, the account has a strong methodological flavour. Sensitive to how we operationalise change, it focuses on the iterative detail of 'how' processes. This approach fills a much-overlooked gap for granularity in micro-orientated process studies.

The first section outlines the type of empiricism that informs my approach. As a pracademic this approach not only shapes how I understand knowledge and see reality it also informs the type of scholar I am and how I came to see the 'problem' underpinning this article. Each subsequent section drills into the sequenced stages of understanding and use, culminating in a brief final segment that aims to make sense of an 18-year experience.

The craft of pracademia: navigating the complex terrain of understanding and use

For close to 25 years, I have taught at the LSE (London School of Economics and Political Science). Here, I am a Visiting Professor in Practice of Organizational and Social Psychology - I teach a specialised MSc course aimed at bridging theory and practice by addressing emerging issues in organisational life. Alongside this, I have a non-traditional educational role - I design and deliver customised executive educational experiences for commercial organisations (Anderson & van Wijk, 2010). These experiences are usually short formal programmes aimed at the specific needs of a particular organisation or cohort (Tushman & O'Reilly III, 2007). Education is my second career. Prior to my current life, I was an Investment Banker, working for 16 years as a US government bond salesperson and a fixed income derivative structurer.

As a practising social psychologist, I operate between the realms of rigour and relevance. I straddle the settings of theory and practice (Tushman & O'Reilly III, 2007) via a 'third road' (Fukami, 2007), a mediating position that involves translating knowledge to make it contextually fit-for-purpose (Dobson, 2012). In this role, I employ strategies of re-contextualisation (Evans & Guile, 2012) acting as a sense-giver (Sutcliffe & Wintermute, 2016), a role often described as a 'pracademic' (Posner, 2009). This space is far from unproblematic (Carton & Ungureanu, 2018). As neither a pure academic nor a full-time practitioner, it is a role that lacks a clear-cut identity (Vroom, 2007) and one that can be seen as sapping the purity of understanding from either domain. The words of an old Italian expression are instructive in capturing this tension; 'Traduttore, traditore', every translator is a traitor (Shearn, 2016). Despite this, mediating the dual considerations of understanding and use has been the driver of my career over the last 25 years. In this space, I am both a theoretician and a practitioner of practice.

Background to the 'problem'

As an executive educator, I tend to witness a recurring phenomenon. No matter how 'successful' a learning programme has been (e.g. top evaluations), I am struck by how quickly participants seem to revert to their 'normality' egged on by the action, traction and distraction of their working lives. I often cheekily suggest that as soon as participants walk out of the classroom, I can see them actively forgetting everything they have learnt. This seems to strike a chord - it invariably brings a knowing, guilty smile to faces. Many of them have been in this position before, a feeling I suspect that most of us have experienced at some stage.

The challenge of post-programme application is part of a wider problem surrounding the utility of formal programme knowledge in organisations (Faragher, 2016; Glaveski, 2019). In 2024, the global market for training and development was estimated at US$354.97 billion (Research and Markets, 2024). Leadership development makes up an important segment of this. In 2023, organisations spent an estimated US$77.9 billion on corporate leadership programmes, a figure expected to grow to just short of US$200 billion by 2033 (Khandelwal, 2024). As organisations face complex, often existential challenges, this would appear to be money well spent (Huggel et al., 2022). That said, very little is known about the effectiveness of this investment (Baldwin et al., 2017b). This situation is not helped by opaque approaches to evaluation. In reality, most organisations only measure the 'success' of their programmes at the level of reactions and satisfaction (Murray, 2019), something with little meaningful link to behavioural change and outcomes (Saks & Burke-Smalley, 2012; Sitzmann et al., 2008). This has troubled me over the course of my career. What is the point of doing what I do if the backbone of my approach achieves only the illusion of change? Given the expense of programmes, am I just contributing to some form of '(great) training robbery? Or, worse still, might the whole logic of leadership development be questionable? (Rock & Cassiday, 2024).

I have sought answers to this problem throughout my career. Wearing my academic hat, my first port of call was the existing literature. Surely, I said, I can't be the first to notice the issue? It soon became clear that literally thousands of articles, journals and books had been devoted to the topic area (Sitzmann & Weinhardt, 2018). What was also clear was that the 'signature' research, the 'transfer of training' literature, had produced few significant breakthroughs (Ford et al., 2018) while simultaneously achieving a state of saturation and stasis. Alongside this, alternative perspectives questioned the basic legitimacy of formal learning interventions and whether they could ever lead to meaningful change (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1999). Whatever the approach, there was almost no consideration for what happens after a formal programme (Baldwin et al., 2017a; Blume et al., 2010) - for some reason, any meaningful understanding of this context was written out of the texts. This space, the space that ultimately matters for application and use, was largely invisible.

The more I explored the problem, the more it became clear that there was an additional issue at play - something about the relationship between different types of knowledges and their contexts. Early in my research, a Special Edition of the Academy of Management Journal captured this focus on knowledge types quite nicely (Rynes, 2007). Upfront, the editors made the standard plea to contributors for articles that could improve the uptake and impact of ideas in practice. Ultimately, they noted something, however, that resonated strongly with me; the findings presented in the edition, they admitted, bore little connection to the everyday life of practitioners, especially in terms of how their methodology represented the reality of the workplace.

'The real-world of...(the) manager is messy, complex and filled with human drama, making it unlikely that it can be completely understood using 'hands off' methodologies such as surveys and archival analyses'

(Editor's foreword. Rynes, 2007)

This observation made me wonder about the characteristics of the domain in which 'formal' knowledge is generated (e.g. the classroom) and those where it is used, consumed and applied - the 'real world' (McIntyre, 2005; Vaill, 2007; Weick, 2005). Could it be that findings that are legitimately produced and presented in one context and fit-for-purpose for that context, did not connect in other contexts because different rules or dynamics applied? (Astley & Zammuto, 1992). Aspects of this distinction resonated with my own experience. As an executive educator, I often work closely with 'star' academics as programme faculty members. More often than not, if a scholar insists on communicating their ideas via an academic approach, they find it hard to connect with practitioner audiences (Markides, 2007). Far from a need to communicate more clearly or dumb down their content (Shapiro et al., 2007), the issue seems to touch something more fundamental - a difference in the way that knowledge is valued and understood between the academic and practitioner realms (Langley, 2019; Langley et al., 2013; Tushman & O'Reilly III, 2007).

As the years passed, I developed a hunch that knowledge produced during a learning programme changed in some way as it moved out of the classroom. I was prompted in this regard by the work of Donald Schön (Schon, 1990). Buried deep within the first chapter of his seminal work on reflective practice is a metaphor about the 'mountaintop' and the 'swamp' (Schön, 1984). Schön suggests that there is a choice to be made while navigating the mixed topography of professional practice, a choice between the hard, high ground where clarity of technical understanding is possible and the swampy lowlands where tangled messiness dominates the terrain.

'There are those who choose the swampy lowlands. They deliberately involve themselves in messy but crucially important problems and, when asked to describe their methods of enquiry, they speak of experience, trial and error, intuition, and muddling through.

Other professionals opt for the high ground. Hungry for technical rigour, devoted to an image of solid professional competence, or fearful of entering a world in which they do not know what they are doing, they choose to confine themselves to a narrowly technical space'

(Schön, 1984, p. 42 & 43)

This passage had a profound impact on me. It appeared to capture the essence of a longstanding dilemma in my field of practice, a choice often portrayed as a binary decision between rigour or relevance (Ghoshal, 2005; Van De Ven & Johnson, 2006). Intriguingly, it also seemed to give me a way of talking about something deep and visceral, something that I had experienced but often found difficult to articulate (Astley & Zammuto, 1992). As an academic, I had made a choice early in my career to pitch my metaphorical camp halfway up Schön's mountain - at a place where I could occasionally get a clear view but also had access to the everyday context of organisational life.

The more I considered Schön's distinction, the more I found myself returning to the implications of his parable. Often it felt that the requirements of so-called 'rigorous' quality research located high on the mountaintop, meant that an issue under investigation needed to shake off the excess baggage of contextual detail, focusing instead on a core theoretical problem (Degama et al., 2019; McLaren & Durepos, 2019). This raised a significant issue for me - it appeared that it was this very detail, the background contextual noise, that gave the swampy real-world setting of organisational life most of its meaning (Langley et al., 2013). From this perspective, the parable seemed to capture a crucial ontological and epistemological distinction between these domains while also exposing the sinewy relational tension between the 'worlds' of theory and practice. As eager academics climb the designated mountain to get a clearer view of their topic, the process of climbing ever higher appears to drive a wedge between them and the practitioners below. These practitioners are not focused on the valiant efforts taking place above them - they are engaging in the daily grind and multiple dramas of organisational life (Langley, 2019), busy throwing mud at one another (Blackwell, 2008) and desperately seeking some way of making sense of what is going on around them (Weick, 2005). Ultimately, either side becomes so absorbed in their respective activities that they lose interest in one another.

This way of thinking had a considerable impact on how I viewed my role as an educator. There seemed to be a need to take classroom knowledge and rekindle it in a way that was fitting for the workplace. This required adopting some form of mediating role and actively bridging knowledge between contexts (Dobson, 2012). Practically, the work of Karen Evans and her colleagues (Allan et al., 2015a; Evans et al., 2009a, 2010a, 2011; Evans & Guile, 2012; Fettes et al., 2020) brought the changing role of knowledge(s) to life for me. Their work on recontextualisation became central to how I approached the process of programme design and delivery. That said, it often felt that I championed this position somewhat surreptitiously. In particular, any commitment to re-contextualisation competed with the powerful presence of the 'transfer of training' literature within my field (Hughes et al., 2018). As the name suggests, Transfer places significant faith in the predictive power of a range of variables to deliver change in the workplace (Evans et al., 2010a). In so doing, it renders the granular detail of the post-programme context almost invisible. This did not feel right to me. No matter how powerful the claims surrounding programme learning might be, learning seemed to lose its spark when it came to the messiness of application and use in the workplace.

Recontextualisation shaped me as an educator. Yet the more I adopted it, the more I felt there was something missing, something to do with the role of time. I had a hunch that programme participants returned to their workplaces and quickly became drawn into contexts that were saturated with a distinct type of temporality. Furthermore, it felt that this saturation was far from neutral and that it had an impact in some way on a participant's ability to practise their learning commitments (Burkeman, 2019). Most of all, I suspected that time was more than just some linear, undifferentiated backdrop to activity (Adam, 2004) - it was a rich, multiple and complex phenomenon (West-Pavlov, 2012), a phenomenon that included 'non-linear' features like interruptions (Wajcman & Rose, 2011), elements of flow (Crawford, 2016) and experiences of pace and velocity (Sharma, 2014). These features appeared to contribute to an experience of shock for many participants, something that had a detrimental impact on the integrity of well-meaning commitments.

Operating in a mediating space has had a significant impact on how I position myself. My work, I would suggest, fits most comfortably within the realm of use-inspired 'basic' research (Stokes, 1997). This approach aims to make a day-to-day practical contribution to people's lives while seeking to answer fundamental questions in novel ways. In being close-to-practice (Cooke, 2005), I also seek to be close-to-practices. While policy is important to me, the majority of my work is concerned with changing practices (Moran, 2015), those things that people do day-to-day in pursuit of their actions. In Schön's parlance, I am interested in enabling others to navigate the tangled complexity of the swamp instead of issuing proclamations from the mountaintop. The nature of my work, therefore, is about being close-to-practice, practices and practitioners.

Outline of the paper: a process approach

In this article, I argue that we underestimate the richness and complexity of the practitioner at work, particularly our relationship with temporality. I suggest that time shades our life and work in multiple, diverse forms (e.g. orientation, pace, disruption, and visibility). These times always say something about who we are (e.g. they are deeply identity-laden) and represent to ourselves and others what we consider to be normal. Deeply saturating our experiences, temporal practices become embedded in our habits and routines, enabling and constraining our ability to act.

Our relationship with temporality is most starkly visible in the wake of a formal learning programme, when participants often return to their workplace with commitments to change. I contend that these commitments most often fail because they overlook the deeply normative and symbolic qualities of time. In attempting to spend our time differently, we enter a period defined by conflict and contradiction, creating a liminal space that, in many cases, challenges who we are and what we want to do. This process is made more complex by the deeply social nature of existing temporal expectations.

The central purpose of the research was to explore what happened when participants returned to work after a 'successful' programme - it sought to make that aftermath visible. The study had three interrelated objectives. First, to reveal the temporal experiences of putting new knowledge to work after a learning programme. Second, to develop a practical intervention - a temporal visualisation tool - to facilitate the practising of personal change commitments. Third, to implement and use the tool, so that it could make a tangible difference to everyday workplace practices. Holding rigour and relevance in equal measure, the study was driven by the dual considerations of understanding and use.

Evidence was provided by an action-orientation case study that spanned 18 years (2006-2024). The site was a European multinational company grappling with the strategic challenges of energy transition. Central to this transformational change process was a highly-rated experiential learning programme with a 'double-loop' learning focus (Chaturvedi, 2021).

The study employed a range of methods and was underpinned by a detailed ethnography, e.g. I physically 'lived' at the company for a total of 356 days, 24 hours a day, between 2006 and 2018. The primary output of the study was a visualisation tool that sought to chart the temporal topography (a 'timescape') experienced by participants after the programme. Recontextualisation framed data capture, analysis and representation while Process methodology supported the development of the tool over a 5-year period (2012 - 2017), as well as its use, evaluation and testing during implementation (2020 - 2024). Ongoing cycles of feedback, reflection and reflexivity contributed to the evolving shape of both the programme and the research - this process covered 75 separate programmes, with 1,875 participants, between 2006 and 2024. The conceptualisation of a programme participant was ultimately informed by a modified symbolic interactionist approach.

The findings were stark. They suggested a steep fall-off in the practising of commitments as participants returned to their workplaces (e.g. a 2-point fall in satisfaction with practising - on a scale of 5 - in the first 18 days). The periodicity of the post-programme context (the 'timescape') was punctuated by a series of distinct stages, each saturated with complex dimensions of temporality. Here, norma-temporal practices, the dilemmas and contradictions of liminality and the interactional expectations of others combined to 'crowd out' the practising of well-intentioned change commitments. Overall, this produced a sense of 'temporal shock'. The use of the tool appeared to offset this - it produced significant results over five pre-defined evaluation criteria (satisfaction and engagement rates, behaviour change, change stories and revenue contribution). The tool was submitted for an industry-led excellence award in 2020 (Brandon Hall Global Excellence Award). It won a gold award, achieving the perfect score of 30/30.

There was, however, a painful sting in the tail of this 'success'; in particular, the tool struggled when it came to its application in the 'real world'. This contributed to a shift in methodology, a resolution that could only have occurred by recognising the pliability of validity between different contextual settings (Wefald & Downey, 2009). It also touched fundamentally on the relationship between time and different levels of analysis, understanding and use. Ultimately, navigating these temporal tensions would herald the end of the study in April 2024.

The essay provides a detailed statement of record of this long-running study. It draws heavily on previously unpublished material (Rogers, 2020) - work that has been reshaped, extended and reinterpreted during my time at the IEA. The document is limited in its scope. In focusing on the role of time after formal programmes, it excludesconsideration of a range of other topic areas, e.g. the role of programme content, pedagogy or other dimensions of context (e.g. space). The intention is not to underplay any of these but rather to prioritise and underscore the neglected role of time.

The paper is formatted to highlight how understanding and use unfolded in an iterative fashion over time. Multiple 'failures' and 'successes' embedded within ongoing loops of reflection and learning contributed to the 'final' finished output. These periods are segmented into sections, each loosely associated with a stage of understanding and use - this underpins the process nature of the work. Much of the content is strongly methodological in character. In seeking to provide visibility to the post-programme context, it focuses on understanding the 'how' as well as the 'what' that lies behind the process of exploration. It also recognises that visibility is sold short by the restrictions of written text (Davison et al., 2012), the narrative is therefore accompanied by a comprehensive set of visualisations within the appendix.

Living in and over time has wider implications, many of which I did not expect when I first started the study. It challenges the worth of a US$350 Billion Learning 'industry' that pays little heed to the application and measurement of its core offering. It also highlights the role of temporal context on agentic individuals and the extent to which agency is compromised by the diminishing gap between stimulus and response. This has profound implications for our ability to reflect, learn and act. The limitations of space prohibit a wider discussion of these implications - they will be covered comprehensively in a separate follow-up document.

Finally, this work has a distinct personal quality. As a researcher and practitioner, I was a central character in this story, and it would be wrong to write myself, in some disembodied fashion, out of the text. For this reason, much of what is presented is in the first person. While this may, on occasion, feel awkward to traditional academic audiences, I have sought to maintain high standards of academic integrity and rigour throughout. In doing this, elements of description, analysis and discussion are integrated to maintain the unfolding flow of the process structure. I have also tried to maintain affinity not just to what I knew but also when and how I knew it, so citation, in most cases, reflects the state of knowledge at a particular point in time. The challenges of this format mean, I suspect, that multiple omissions, oversights and shortcomings have crept into the text. I apologise in advance for these, and in the spirit of collaborative endeavour, I look forward to collectively iterating to a better place of understanding and use over time.

2006 - 2012: The complexity of context - creating the successful illusion of change

Let me start by saying something about the context in which this study took place, e.g. the company Forum, the learning programme Impact and the challenges the programme sought to address.

Too often, context is presented in research studies as an undifferentiated blank sheet (Baldwin et al., 2017a). This is neither helpful nor realistic. The granular, fragmentary detail of organisational life makes up the canvas on which activity is written (McLaren & Durepos, 2019). This canvas is the surface upon which the output of formal learning programmes, participants' change commitments, seeks to write a different story, both for themselves and their organisation. It is important, therefore, to describe the nature of this canvas as it both enables and supports a certain way of operating. That said, this canvas also channels and constrains activity via an invisible sub-structure that is often resilient and impermeable (Lahlou, 2024). This is a significant problem for the output of formal learning as it can create the illusion of change - a belief that something has been done to bring about change, but there is no meaningful evidence that visible change has occurred. This issue of visibility, in multiple forms, loomed large over the course of the study.

In 2006, I attended a meeting at a leading international energy company to discuss how the company might approach changing their assumptions around shaping commercial value (Argyris, 1977). As someone with a financial background, social psychological training and a keen interest in climate change, I found this conversation fascinating. A long-term interest in energy transition meant that I saw this potential engagement as a chance to have a front-row seat in making a difference to the future of the planet. As the opportunity developed, it became clear that the suggested approach to change was primarily micro in nature. Central to this was a belief that key actors and small groups would operate organically from the middle of the organisation to bring about change (Lüscher & Lewis, 2008). This, I felt, was a sensible strategy. I had confidence that the logic of climate science provided compelling momentum behind the need for the energy transition. Alongside this, I saw an opportunity to provide the behavioural architecture to equip key actors in reshaping the mindset of dealmaking around transition. In December 2006, I accepted the position of Lead External Faculty for a flagship learning programme to drive the initiative.

Forum: a company facing disruption

'Forum', a pseudonym employed for this article, is a European transnational corporation in the global energy business. Established over 100 years ago, it is a household name operating in over 70 countries and employing close to 95,000 people.

For most of its existence, the company has been a market leader in its field. This position of dominance has been achieved primarily due to its technical capability, market knowledge and global network of businesses. In recent years, the company has experienced significant changes in its commercial and competitive environment. Volatility in commodity prices has impacted its profitability, while shifts in digital technologies have disrupted many aspects of its business model. Most of all, the ongoing process of energy transition has threatened Forum's licence to operate at multiple levels. These factors have made it increasingly difficult for Forum to execute the type of commercial deals it needs to operate successfully as a company.

In 2007, senior management at Forum took steps to guarantee its long-term survival as a company. It set up an internal, business-led Academy to formally equip its front-line professionals for a very different commercial setting. The Academy set out four parameters to underpin its approach to change. First, transformation - a belief that change would challenge established ways of thinking and that this shift would have significant implications for how Forum's employees operated. Second, value - the need to understand 'what really mattered' to Forum and its expanding, increasingly diverse, stakeholder base. Third, critique - the need to challenge deep, taken-for-granted assumptions surrounding the relationship between Forum and its stakeholders. Finally, doing - the need to ensure that changes in thinking are linked to changing behaviour and application in the workplace.

In 2007, the Academy set out plans for a learning programme (Impact) that would spearhead the process of change within the company's senior deal-making community. Impact became the learning programme underpinning this study.

A transformational learning programme: Impact

Impact is a double-loop learning programme that aims to challenge assumptions around value and stakeholder engagement (Chaturvedi, 2021). The structure of the programme has evolved significantly since its inception. Between 2007 and 2010, it operated as two 3.5-day face-to-face modules with a six-week break between each leg. In 2010, the Programme integrated its core components into one 5-day face-to-face module, which was slimmed down to a 4-day structure in 2015. In the wake of COVID-19, the programme adopted its current form: a 10-week virtual design.

Impact has a strong experiential character, placing a premium on contextualisation and relevance; it combines pre-programme, 'face-to-face' and post-programme activities. The face-to-face component (carried out virtually via Teams) is based on two, rolling customised simulations that extend over 18 time zones. The programme has three key 'content' themes: challenging assumptions ('orthodoxies'), appreciating perspectives of value and shaping purposeful relationships. With a strong 'open-skill' orientation (Blume et al., 2010), the programme provides participants with the flexibility to develop their specific needs within the broad conceptual parameters of the three content themes. These parameters provide the backbone for the experiential simulations, which employ a group of 7 actors, the majority of which have been engaged with the programme since its inception. The nature of the simulations reflects live, visceral scenarios that test and challenge participants' abilities to shape deals in rapidly changing settings. The overall driver of the simulations, and the programme in general, is to enable change in the workplace and achieve the wider goal of broadening perspectives on value.

From the outset, Forum management required Impact to be robust both from a practical and theoretical perspective. Over the years, this approach crystalised into an informal set of beliefs underpinning Impact's design and delivery. These held that change is a function of both the person and their context (Lewin, 2007), that the changes facing the typical Impact participant often have transformative identity implications (Mezirow, 2009), that transformative change involves a range of conflicts and contradictions (Engestrom, 2010) and that these conflicts require deep, taken-for-granted assumptions ('orthodoxies') to be challenged at multiple level. Finally, there was a belief that learning and activity is not just an individual act - it requires wider social support and scaffolding (Daniels et al., 2007) as knowledge moves from the classroom to the workplace.

Impact participants: a complex change profile

Impact participants are experienced commercial dealmakers - employees who organise, structure, and negotiate the large-scale transactions that shape the direction and future of their businesses. The typical participant profile is usually mid-career (35+ in age), male (60%), with a strong technical background and high level of academic achievement (many to doctoral level). Participants are drawn from across Forum's businesses and are required to have a minimum of 5+ years of deal-making experience. Registration is by nomination after a rigorous selection process. In general, participants would typically be described as knowledge workers (Newell et al., 2002). At Forum, the nature of business knowledge tends to be highly technical and strongly quantitative.

Two aspects of the typical profile make change a multidimensional experience for participants. First, the majority of participants are facing career transitions that often involve significant 'threshold' changes in both their work and life (Donovan, 2017; Vidal et al., 2015). Second, the nature of a mid-career change journey, similar to many complex organisations, is not clear-cut (Sullivan & Al Ariss, 2019).

At Forum, many participants start in specialist technical roles where the focus is primarily on individual performance, expertise and output. At this stage, they are often highly task-focused and work under close direction and supervision (Bass, 1990). Transitioning into a leadership position usually requires a qualitative shift in mindset, behaviours and focus (Lord & Hall, 2005). This shift often brings greater people responsibilities, as well as enterprise-wide decision-making. At Forum, it also tends to require greater relational focus, both inside and outside the organisation. This can make mid-career change extremely challenging (Goldsmith, 2008). Mid-career is usually defined as a period of intra-career role adjustment (Grady & McCarthy, 2008). During this period the meanings an individual holds about who they are and what they do can change substantially (Ibarra, 2004, 2015a), questioning how they and others see them (McMahon & Watson, 2013). This can have significant implications for their personal and social identity (Grint, 2005). It can be further complicated by the ambiguity surrounding the nature of transitions (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2012; Mendenhall et al., 2012) with executives moving to lateral roles, e.g. running a different business as a 'stretch' assignment (Whitepaper & Macaux, 2010). These are often not presented as a formal transition and lack much of the structure and symbolism surrounding change, e.g. labels, rituals and artefacts (A. Smith & Stewart, 2011). This is a challenging mix to roll into any change journey!

Programme participants were not the only parties implicated in the change process at Forum (Crane & Ruebottom, 2011). A broad range of stakeholders formed a complex, relational web around both the programme and the research. These stakeholders included the likes of Human Resources, Learning & Development, teaching faculty, line managers and sponsors (Guerci & Vinante, 2011; Janmaat et al., 2016). The differing perspectives of this diverse grouping meant that the multiplicity of ongoing activities related to both learning and research, could never be fully divorced from the question of underlying interests and politics (Alvesson, 2011). As lead faculty (2006 to 2024), I was also a key stakeholder. As principal programme designer and orchestrator, I taught individual content segments and was responsible for the overall programme narrative and structure. Significant aspects of stakeholder management also fell within my remit. My career profile was helpful in this regard. The 'hard' quantitative and technical skills from my role in financial services alongside the 'soft' qualitative and relational aspects of social psychology were seen as a relatively rare combination in an educator and something that potentially enhanced my credibility in front of Impact's participants and stakeholders.

The role of commitments: linking the mountain top and the swamp

When setting the programme objectives, Forum management stressed the need for classroom learning to translate into workplace activity. Central to this was the role of post-programme commitments.

A commitment is defined as 'a promise or firm decision to do something' (Cambridge English Dictionary Online, 2019). Similar to other programmes, a participant makes some form of change commitment during Impact - a statement of their intent to do something different when they return to the workplace (Goldstein & Ford, 2001). This statement is usually linked to a prior area of development (Quiñones, 1995) and elaborated within an action plan (Kirkpatrick, 2019). This plan is often structured on a S.M.A.R.T. basis, something that is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound (Phillips, 2012).

Change commitments are worth little if they are not practised in a deliberate and consistent fashion (Ericsson et al., 1993). Practising is defined as the ability to 'perform an activity repeatedly or regularly in order to improve or maintain one's proficiency (Lexico, 2019). The role of practising has a long and contested past. The debate about the role of innate qualities (Galton, 1869) or trained ability (Thorndike, 1912; J. B. Watson, 1930) is long-standing and well-rehearsed. More recently, a body of literature has championed the need for deliberate practice in order to achieve expertise across a range of domains (Ericsson & Pool, 2016). This suggests that accumulated levels of practice over time account for individual differences in performance and expertise (Macnamara et al., 2016). Many of the headline claims associated with this literature have fuelled popular beliefs about the power of sustained practising (Dubner & Levitt, 2010; Gladwell, 2009; Syed, 2011). One, the '10,000-hour rule', suggests that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert in any particular field (Ericsson et al., 1993).

Like most formal programmes, sustained and deliberate practising of commitments provided a significant challenge for Impact. At the root of this challenge lay a lack of understanding and visibility about what actually happens to change commitments once participants return to the workplace. To address this, Forum offered one-to-one external (consultant) coaching to participants and encouraged support from internal line managers. One-to-one coaching has become increasingly popular in corporate settings (Grant, 2014). However, with mixed evidence surrounding its impact and effectiveness (Lawrence & Whyte, 2014), coaching can be seen as an expensive add-on to formal programmes (Meuse et al., 2009).

The problem with the visibility of a problem!

By 2012, Impact had become the top learning programme at Forum's Academy. Two success measures were central to this - ratings for programme 'satisfaction' as well as 'commitment to apply'. Across the year (2012), the average satisfaction and commitment scores never dipped below 4.7/5 (5 = Highly Satisfied/Committed to apply). Programme scores were reinforced by qualitative feedback that regularly described Impact as the most significant learning programme experienced by participants (either inside or outside the company). Finally, Impact was routinely oversubscribed with, on average, a one-year waiting list.

This leads to an obvious question - what was the problem the study was looking to address? One of the biggest issues over these early years (2006 - 2012) was the ability of Forum management to (literally) 'see' a problem. For many Forum colleagues, and arguably most of the organisations in which I have worked, there was no problem. The programme was popular, highly rated and had a strong, positive reputation amongst its stakeholders. But this did not feel right. In my mind, knowing after a 'successful' program did not necessarily lead to doing in the workplace; it felt like there was something deeper at play, something that precluded an automatic link between knowledge and action. I needed to investigate this more widely.

2006-2012: The dark shadow of Transfer - exposing the roots of the problem

My first port of call in seeking to explore the problem was the existing literature. Between 2007 and 2012, I undertook a review of the literature relevant to the field of learning application and use. This review covered over 1500 works across a range of perspectives and disciplines. As I progressed, an issue emerged around the theme of visibility. This theme appeared to be related in some way to the dominant lens employed within programme learning, a lens that tends to support what is known as a 'Transfer' mindset, an understanding that knowledge acquired in the classroom transmits in a single movement to the workplace (Evans et al., 2010b). Transfer, as I would find out, casts a long and dark shadow over the ability to see a problem with application and use.

Transfer of training: the dominant learning logic

As a working definition, the transfer of training - referred to here as 'Transfer' - has two key dimensions (Syrek, Weigelt, Peifer, & Antoni, 2016). Firstly, generalisation; is how knowledge and skills acquired in a learning setting are applied in different settings and/or situations. Secondly, maintenance; is the extent to which changes that result from a learning experience persist over time. Transfer research focuses on those factors that are believed to influence, and predict, the generalisation and maintenance of learning (Vandergoot et al., 2019).

Transfer has had a long and troubled history. Despite an extensive literature, what has become known as the Transfer problem is longstanding and enduring (Barnett & Ceci, 2002). From an early stage, the field has been characterised by definitional ambiguity, methodological confusion and measurement challenges (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). Inconsistent and conflicting findings have proved highly problematic, impacting the perceived credibility and usefulness of the approach (Banks et al., 2016). Almost mantra-like, it has become commonplace for academic articles to start with a mention of the 'transfer problem' (Nafukho et al., 2017). Disenchantment with the field has grown in recent years with a belief that investigation of core topic areas has reached stasis and saturation (Bell et al., 2017; Ford et al., 2018).

Exposing the fault lines in Transfer's logic

Many of Transfers' issues are deeply rooted in its methodology. Underpinned by substance metaphysics (Hernes & Maitlis, 2010; Malloch et al., 2010), Transfer presents an understanding of reality that views discrete entities as the fundamental units of existence (Whitehead, 1979). This perspective conceptualises entities as 'forms' composed of a-priori properties that largely maintain their substance over time (Rescher, 1996). Under these circumstances, change does not unduly effect the underlying essence of forms (Tsoukas & Chia, 2002), and the externalities of context are reduced to the level of background noise and interference (Burke et al., 2009). Here, producing the 'transfer ready' trainee is a little different from generating any other form of fit-for-purpose functional object (Weiss & Rupp, 2011).

Tied closely to substance ontology is the logic of variance theorising (Mohr, 1992). Variance seeks to explain differences in a given variable by changes in another or other variables (Hernes & Maitlis, 2010). This leads to a methodological preference for 'what' questions (Ortiz de Guinea & Webster, 2014), supporting a paradigmatic approach to knowledge (Bruner, 1990, 1991; Polkinghorne, 1988; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) where knowing is a function of defined, limited relationships. Variance impacts how reality is represented - much of what happens above, below, before or after the relationships of variance goes missing. Under these circumstances, the richness of the everyday practice experience is rendered largely invisible. This is particularly the case in the treatment of time. In the quest for empirical regularities, variance tends to abstract temporality out of the description of organisational life, producing what Langley has called 'timeless propositional statements' (Langley et al., 2013).

In recent years, a group of leading scholars have called for an overhaul in the approach to Transfer (Baldwin et al., 2017a). In so doing, they have highlighted a range of issues that act as fault lines in Transfers methodological logic. At the most basic level, they suggest that studies rarely present adequate information on either research subjects or their contexts. Throughout the literature, it has become commonplace for Transfer studies to reduce the description of participants to brief, often formulaic profiles - subjects that seem to fall from a 'trainee bin in the sky' (Campbell, 1971) into homogenous, undifferentiated contexts. This is highly unrealistic. As evident at Forum, learning programmes, their participants, and settings are hugely diverse. Alongside this, programme participants are not automatons - they always have some element of active participation in their learning (Bell et al., 2017; Bell & Kozlowski, 2008), a feature that opens up a range of implementation choices in the workplace (Huang et al., 2017).

The nature of research questions is also an issue for Transfer, with most studies seeking to answer 'what', as opposed to 'how' questions. What questions are crucial in highlighting big-picture, macro relationships that form the backbone of traditional scientific knowledge. That said, they are often of limited use when addressing the contested granularity of change in everyday micro contexts. This is the level at which research is most useful to everyday practitioners; those who may know what to do but not how to do it. Focusing on 'what' also renders an incomplete account of temporality as it overlooks how embodied individuals actually behave not just over but also 'in' time (Ployhart et al., 2002). Here, time is an active, foreground ingredient in learning and implementation processes (Mintzberg,2008), an experience that has become significantly more intense for knowledge workers in recent years (Porter & Nohria, 2018).

As an approach, Transfer is beset by challenges of measurement. Once again, this is an issue intimately related to methodology. Establishing an isolated link between variables, however interesting, can feel remote to the experience of practitioners, who most often experience these variables in combination with multiple other features (Baldwin et al., 2017a). This highlights the issue of holism and how achieving 'scientific' validity can seem at odds with its 'real-world' counterpart (Wefald & Downey, 2009). This distinction between different 'thought worlds' (Cascio, 2007) defined the work of F.J. Roethlisberger (Vaill, 2007). Dedicating his career to what he called the elusive phenomena (Roethlisberger & Lombard, 1977), Roethlisberger concluded that the realms of theory and practice often had different knowledge relations to a phenomenon and that these relationships had different temporal characteristics. This meant that the same phenomenon could (and would) be valued differently in either realm (Cascio, 2007; Wefald & Downey, 2009). Resonating more closely to a flow-like understanding of the practice setting (Heidegger, 1978; Winograd & Flores, 1986), this has the effect of divorcing much of what is produced by Transfer research from the wider picture it seeks to portray. Under these circumstances, researchers can become a bit like brick-layers, narrowly focusing on individual bricks while losing sight of the structural integrity of the overall wall (Forscher, 1963).

Measurement is not just a conceptual issue for Transfer - it is also highly problematic when Transfer logic is applied in practice (Murray, 2019). This issue is highlighted by the most common evaluation model employed for formal learning - the Kirkpatrick approach (Kirkpatrick, 2019). Kirkpatrick suggests that programme learning can be evaluated at four levels. Level I measures affective and attitudinal responses ('Reactions'). Level II focuses on what has been learned and acquired in terms of knowledge ('Learning'). Level III evaluates the extent to which participants apply their learning on-the-job ('Behaviour'), while Level IV seeks to capture organisational outcomes ('Results'). Routinely, the majority of organisations only measure formal learning at Level I or II and very rarely at III and IV (Blanchard et al., 2000; Sitzmann et al., 2008). This is highly problematic as there is little evidence of any relationship between programme reactions and the delivery of results and outcomes in the workplace (Saks & Burke-Smalley, 2012).

Finally, the role of temporality is largely missing from dualistic accounts of Transfer (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2011). This was something that resonated strongly with me in the early days of the study. In particular, it appeared that the experience of temporality seemed to have a significant impact on the character of knowledge valued in practice contexts (Weick, 2005). Recognising a link between knowledge and temporality suggested that the relationship knowledge has with any given phenomenon can differ across contexts. What seems entirely reasonable in one setting (e.g. during a learning programme) may not be the case in another (e.g. the workplace after the programme), implying that 'knowledge' from one context needed to evolve and change in some way to be fit-for-purpose in another. This suggested that all knowledge has a context (Bernstein, 2000), and for knowledge to be useful in any specific context, it needed to be recontextualised (Allan et al., 2015a; Evans et al., 2010b; Evans & Guile, 2012). This moved me from the consideration of knowledge as a single and unitary concept to something that is multiple and contextual, a point recognised in recent Transfer thinking (Baldwin et al., 2017a).

Recontextualisation: a mediating approach

Challenging the fault lines in Transfers methodological logic demanded a new way of thinking about programme learning and application. Between 2010 and 2012, I gradually adopted recontextualization as the core theoretical framework both for the programme and, as it developed, the formal study. This became a platform for addressing the five issues highlighted above.

Recontextualisation suggests that knowledges play out in different ways, in different contexts (Evans et al., 2010b), and as a consequence, concepts need to change as they move from one setting to another (Bernstein, 2000). Evans et al. (2010, p. 246) have identified four key processes of re-contextualization (content, pedagogic, workplace and learner recontextualisation), each with strategies that facilitate putting knowledge to work (Evans et al., 2009b).

Overall, I was hopeful that I had found a way forward with Recontextualisation addressing many of the shortcomings of Transfer. It repositioned acquiring learning from a single, simplistic movement to the realm of ongoing processes where context is recognised and actively navigated. Helping to avoid either/or dichotomies, it also kept the active individual visible in their social setting. Here, the nature of this individual is not some bland substance (Weiss & Rupp, 2011); she is an interacting, embodied actor, someone with a biography and history that is always embedded in context (Hosking, 1991; Morley & Hosking, 2003). This individual has multiple roles in their daily life, operating on stages defined by both front and back-stage elements (Edgley, 2016; Goffman, 1974, 1990; Goffman & Berger, 1986; Rosengren, 2015). Crucially, the approach captured the distinct ontological and epistemological characteristics of the workplace setting, something largely invisible in Transfer (Blume et al., 2010, 2019). It also made visible a range of actors with a stake in the wider processes of re-contextualisation. Now, programme design and delivery shifted from a formulaic, value-free activity (Shinall, 2012)to something deeply relational and steeped in contested choices. This was far closer to the reality I encountered in everyday practice.

Central to recontextualisation's appeal was another feature that resonated strongly with me - the role of process. Process perspectives are systems of ideas that explain how a phenomenon develops, evolves and unfolds over time (Ven, 2007). Supporting a worldview that has interaction at its core (Shotter & Tsoukas, 2011), process rests on a relational ontology (Hernes & Maitlis, 2010) where things have meaning relative to other things, e.g. not in their inherent substance. This challenges dualistic understandings of change (Kotter, 1990; Kotter et al., 2011) where entities are seen as separate, discrete, and 'acted upon' by some exterior force (Seibt, 2020). As such, process tends to focus on the journey to an eventual outcome, exploring 'how' as well as 'what' questions (Langenberg & Wesseling, 2016). It implies an interactive, two-way relationship between 'variables' - an approach that shifts the understanding of a phenomenon from being to becoming and avoids the 'fallacy of misplaced concreteness' (Whitehead, 1979:2). Process sees manifestations of substance as inherently contingent, temporary, and constantly in the making. No fixed external point outside the process influences this dynamic (Gergen, 2011; Shotter, 2012) - the plurality of change is located within the process itself (Hernes, 2012).

Despite its attractions, recontextualisation, like Transfer, had an issue incorporating temporality as an active ingredient of change. This, once again, felt uncomfortable. It also highlighted two key questions for me. If time was so important in my analysis, what did I actually mean by the use of the term, and practically, how might an understanding of temporality be incorporated into a workable recontextualisation approach? During this period, a saying often attributed to Albert Einstein kept coming to mind - 'Time is what the clock says'. This seemed to touch on something quite profound. It intimated that the representation of the mechanical clock, a view of time that is quantitative, linear and exact, has become so familiar that it is often difficult to conceive of 'time' in any other way. I felt that this underplayed the richness of how we experience time, especially temporality at work. I needed a way of thinking and talking about time that did justice to this richness - to do this, I had to look backwards before I could look forward.

Seeing temporality: linear and non-linear time

For millennia, our ancestors tracked solar and lunar cycles (Stix, 2002). In the thirteenth century, the invention of the mechanical clock changed all of this (Landes, 1983) - overnight time literally lost its fluid, cyclical quality, and the introduction of a standard temporal unit heralded an era of increasing precision and standardisation (Castree, 2009). Industrialisation saw the mechanical clock become the root metaphor for efficiency and performance (T. Watson, 1995) and, with this, the organising principle of a new modernity (Winner & Mumford, 2010). This framing supports our contemporary understanding of time as absolute and objective - a singular, external concept that is precise, measurable and linear (Bunnag, 2017).

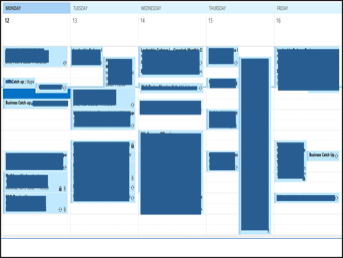

The concept of linear 'clock' time is deeply embedded within organisational life (Sharma, 2014). For many, the working day is a constant stream of tasks, meetings and commitments that need to be squeezed into busy, fast-moving schedules (Mintzberg, 2008). In an era of connectivity and knowledge, the central role of the mechanical clock has been reinforced by other forms of temporal management, most notably the mobile phone and the electronic diary (Ojala & Pyöriä, 2018; Stieglitz et al., 2015).

Ways of seeing are often ways of not seeing (Berger, 2008; Morgan, 1997), and how we frame time is no exception to this. Broader understandings of time are characterised within the literature in a variety of different forms, e.g. qualitative (Hassard, 1991), social (Moran, 2015) or non-linear time (Crystal, 2001; Sleek, 2018). For clarity, I refer hereafter to this broader understanding by the last of these, 'non-linear' time.

Non-linear time has multiple, diverse facets (Cipriani, 2013). Less clear-cut than its quantitative counterpart, it is open to interpretation at many levels. At an intra-individual level, it may focus on how time is impacted by our biology (Wright, 2002) or personality type (Myers & Myers, 1995). From a social perspective, it can relate to the effects of generation, gender (Kleinman, 2009) or culture (Levine, 2006). It can also play to the situated and subjective processes that impact the perception of time (Flaherty, 2000) or highlight the societal experience of time as interruptive or disruptive (Newport, 2016). These understandings shift the underlying metaphors of time from exacting linearity towards cyclicality, rhythm and flow (Crawford, 2016). They move us away from efficiency, performance and use towards a wider focus on meaning and symbolic sense-making (Flaherty & Fine, 2001). All the while, time shifts from a singular, passive concept to one that is multiple, varied and active - from time to times. This, I felt, was the type of temporality I saw operating in everyday organisational life. But recognising this was not enough; I needed to move beyond the conceptual and, most of all, be more specific about the practical dimensions underpinning this broader understanding.

Dimensions of temporality

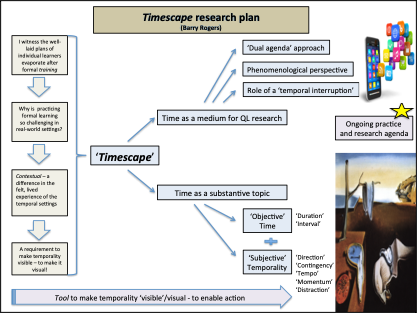

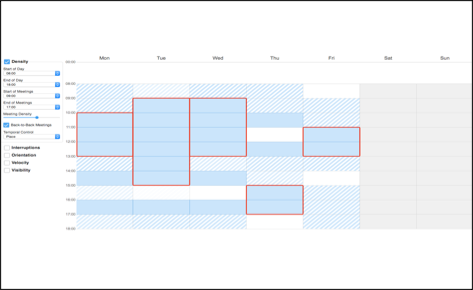

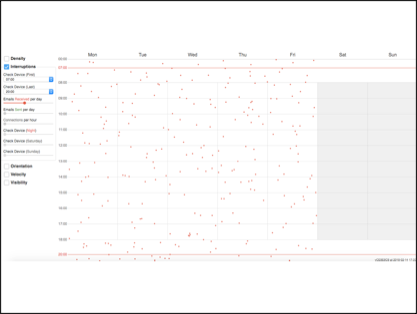

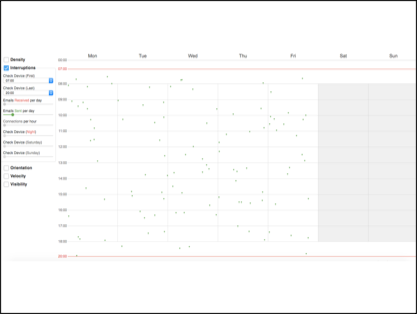

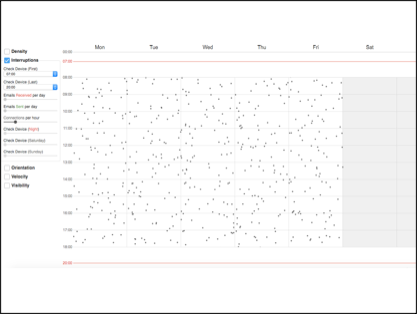

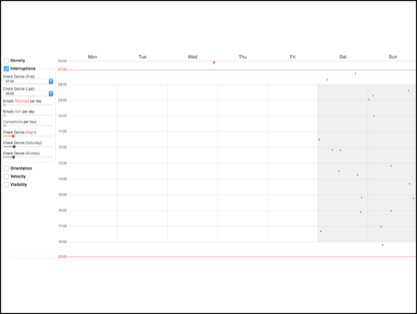

During this period, an in-depth review of the literature highlighted five dimensions of temporality that appeared to form part of a wider 'timescape' associated with the application and use of formal knowledge (Adam, 2008). I came to describe these dimensions as Temporal Orientation, Visibility, Velocity, Density and Interruptions.

Orientation highlights the directional preference associated with an action (Bugaric, 2019; Park et al., 2016), e.g. a tendency to associate greater value with the past, present or future (or any combination thereof). Arguably, the post-programme setting represents a special case of Kierkegaard's maxim of 'living forwards' (Ree, 1998). This dynamic goes to the heart of the valuation equation in finance, e.g. an organisation's worth being the present value of all future cash flows (Berk & DeMarzo, 2013). Via this frame, minimal value is placed on past events, and time becomes an open-ended orientation towards an emerging future (Mintzberg, 1980).

Visibility captures the level of felt certainty in the general temporal setting. Many organisations operate in a commercial and competitive environment that is increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (Euchner, 2013). This feeds a mindset of temporal fragility that can seep into everyday organisational life (Horney et al., 2010). In doing so, it often undermines the efficacy of past knowledge, focusing instead on immediate and forward-looking possibilities (Horney & O'Shea, 2015).

Velocity captures the perceived pace of a temporal setting (Boersma, 2016). For many, the ubiquity and pervasiveness of information and communication technology have contributed to a belief that organisational life has accelerated in recent years (Wajcman, 2015). This can have significant implications for the relationship that many workers have with knowledge, e.g. to what extent is there time in the working day to think and reflect, and when thinking does occur, what sort of knowledge is valued? (Basar et al., 2015).

Density captures how time is employed and used (Coffé, 2015). Central to density are meetings - these constitute a significant feature of organisational life for knowledge workers (Perlow et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2012). Meetings can be face-to-face or virtual, formal or informal, internal or external. In many cases, the scheduling of meetings is not within the control of the individual worker - electronic diaries are often open and transparent to colleagues to schedule meetings as they see fit (Cross et al., 2016). This can raise serious questions about how time is used (Wajcman, 2018). To what extent are workers pulled along by the relentless momentum of packed meeting schedules? How are these meetings linked to habitual behaviour and automatic thinking styles? Ultimately, where is the time to practise new learning commitments if no 'space' is available?

Interruptions capture the range and variety of disturbances experienced in a work setting (Leroy & Glomb, 2020; Puranik et al., 2020). Whether physical (e.g. a tap on the shoulder) or virtual (e.g. checking email) interruptions represent a growing literature in philosophy (Gibbs, 2010), social psychology (Christianson et al., 2008) and learning (Jarvis, 2010). This growth is not without cause. Through the use of information and communication technology, many workers find themselves operating in multiple workspaces simultaneously (Crang, 2010), something that has significant implications for concentration, focus and attention (Leroy, 2009).

While these dimensions were useful in shaping a broad understanding of time, a significant question remained outstanding for me. I wondered how these times exhibited a hold over our working lives, and especially our capacity to act and change? Anecdotally, I started to ask participants on my programmes about the obstacles they encountered implementing their commitments - time, in its multiple forms, always seemed to be a part of the responses. In 2011, I decided to test this hunch more systematically. To do this I ran a short, simple experiment on the final afternoon of programmes I was facilitating. I gave each participant a small cardboard box and asked them to answer one question. 'What normally gets in the way of practising your change commitments after a programme?' I then asked them to write their immediate thoughts on each side of the box (8 responses). Across 45 separate exercises in different organisations, time made up over 40% of the responses, the largest single category recorded. This exercise was repeated in a variety of settings over the next 7 years.

One final question remained. How did these times manifest themselves in everyday life? A route to answering this appeared to lie in the role of practices. Moran (2015) suggests that temporal experiences are more than abstract phenomena; they represent enacted, material practices that organise the social functions of temporality (Moran, p. 289). This way of thinking was a breakthrough for me. Seeing time as social practices made it accessible and relatively easy to comprehend. This addressed a recurring challenge faced when researching time - how can a respondent talk about something so rich and deeply experienced but simultaneously abstract and invisible? (Levine, 2006). The five temporal dimensions, linked to social practices, became a way for me to think and talk about time in a tangible manner.

So, where did this leave me? As I stepped beyond the shadow of transfer, recontextualisation became the central theoretical frame for the next stage of the study. This approach was supplemented by an understanding of time - linear and non-linear - based on five temporal dimensions. These dimensions came together to portray the post-programme context as an active timescape, a context where learning commitments competed to take hold on a canvas already defined by embodied temporal practices. This felt like progress.

But now I had a niggle that would not go away. How could I practically do something with this novel conceptualisation? Sitting in front of people and lecturing them about the role of times, no matter how interesting or insightful, did not feel as if it would make a lasting difference. I started to think about a central conceptual thread of the research - ways of seeing. If the underlying problem was in some way related to visibility, then maybe this also provided a solution route? I wondered how I could make the idea of multiple 'times', literally, visible? Alongside this, how could I shape something that generated understanding but was simultaneously practical and usable? By late 2012, my thoughts started to turn to the role of visualisation, and particularly as a temporal tool.

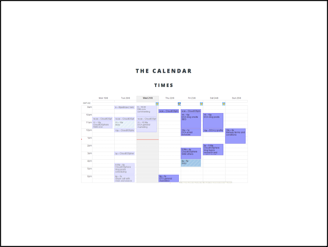

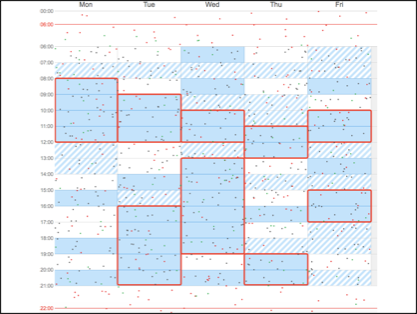

2013-2018: Evolution of a visualisation tool - making visible temporal-shock and the topography of time

The years 2013 to 2018 represented the formal phase of the study and the period over which the visualisation tool took shape. The tool was based around a ubiquitous feature of contemporary organisational life, an online calendar (Feddern-Bekcan, 2008), the go-to place in terms of time use and availability within organisations (Porter & Nohria, 2018). The development of a working tool was categorised into six distinct stages. Each stage signalled, a) an evolution in the specificity of the visual representation and b), an advance in the tools' operational form. These periods can be summarised as follows:

1. 'Exploration' (2013 - June 2016)

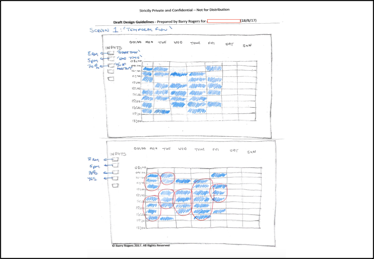

Period one was defined by attempts to think creatively about how post-programme practising might be supported by some form of process or artefact (e.g. a mobile app). Alongside this, an understanding of the multifaceted nature of time, and particularly its visual representation, became a driving feature of the emerging design.

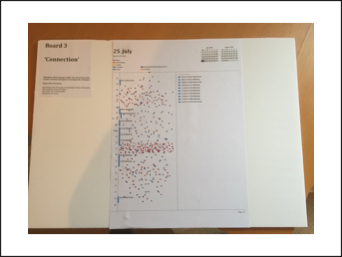

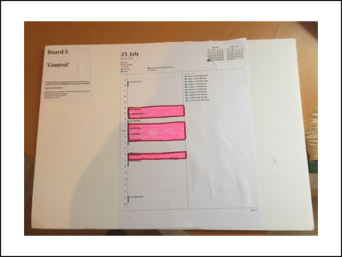

2. 'Sense-making' (July 2016)

The second period saw the initial attempts at representing linear and non-linear time in visual form. The output from this phase took the shape of 6 physical storyboards, each presenting a different temporal dimension within a generic 'calendar' backdrop.

3. 'Credibility' (August 2016 - March 2017)

Period three was driven by the need to establish a non-working prototype. Throughout 2016/17, I produced an online presentation that displayed the key elements of the storyboards. This presentation was then used at Forum to build credibility for the tool and its methodology.

4. 'Construction' (April 2017- December 2017)

The fourth period saw the first attempt at producing detailed plans for an interactive working tool. This involved 2 phases of in-depth 'tool-design' interviews (a total of 21 individual interviews), multiple hand-drawn visuals and ultimately a design brief.

5. 'Operational simplicity' (January 2018 - August 2018)

An initial working model of the tool was finalised in February 2018. This was tested with potential users (n = 8) during two sets of Pilot Interviews and resulted in four beta versions of the tool over the following five months.

6. 'Use' (September 2018 - March 2019)

By July 2018, the tool was ready for use. The application and evaluation phase took place in the wake of an Impact programme in September 2018.

The visual representations of each of the above stages appear in the Appendix.

To navigate the iterative process of tool design, I required a rigorous and credible approach to evidence. Ultimately, this involved intermingled processes of data representation, data capture and data analysis. The requirements of understanding and use dictated that my eventual output had to make a contribution both within the Academy and in the world of Practice (Astley & Zammuto, 1992; Banks et al., 2016; Ghoshal, 2005). With this in mind, the study aimed to connect with a growing debate around re-imagining quality research (Degama et al., 2019). Recognising the challenges of neutrality and objectivity (Cunliffe & Alcadipani, 2016; Donnelly et al., 2013; Hatch & Cunliffe, 2012; Koning & Ooi, 2013; Peticca-Harris et al., 2016), and that 'good' accounts are rarely clean and tidy (Vickers, 2019), I actively sought to embrace the disorder and messiness of the practice setting at Forum - the 'swamp' (Hurd et al., 2019). This had fundamental implications for how I approached data e.g. I needed to represent, capture, analyse data both 'in-flight' and after-the-fact. It also required me to relax the taboo of the first person, 'share tales from the field' (Cunliffe & Alcadipani, 2016, p.2) and underscore the performativity of the research process (Ashcraft, 2017). Most of all, generating credible evidence required a detailed focus on methodology - the intermingled processes of data representation, capture, and analysis came together to underpin this need.

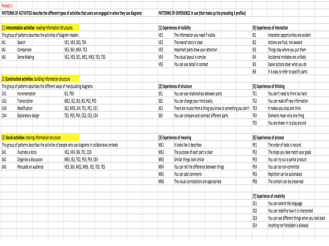

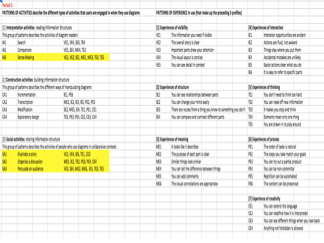

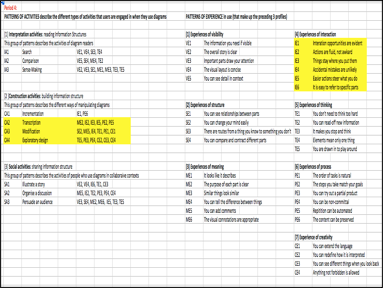

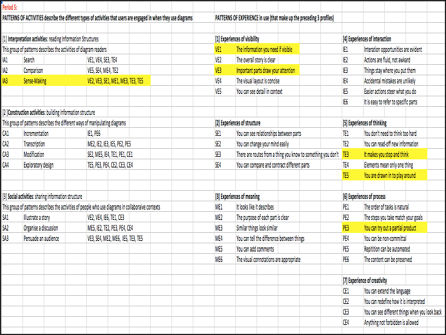

Data Representation

The representation of a temporal tool demanded much more than an aesthetic activity. To achieve this, I employed Blackwell's Pattern Languages (2020), a modified form of Green's Cognitive Dimensions of Notation (Green, 1989). This approach seeks to capture three activities typically engaged in when someone uses a diagram - activities involving interpretation (e.g. reading information), construction (e.g. building information) and cooperation (e.g. sharing information). These activities are further divided into a variety of sub-activities (e.g. different ways of modifying, exploring, or transcribing) and are ultimately linked to a range of user experiences. Overall, the approach sought to underscore the belief that visual representation often holds 'active' potential (Pauwels, 2005) and, quite literally, can be seen as more than passive additions to verbal texts (Miko, 2011). Employing a dialogic orientation (Meyer et al., 2013), this positioned visuals as a means of triggering rich responses to hard-to-talk-about experiences (e.g. time) with the follow-on potential to make tangible links between these experiences and underlying practices.

Data Capture

Constructing a working tool involved different relationships with data - it both required and produced data. A range of interview types, qualitative and quantitative, made up the core of formal data capture. In total, 157 interviews, over 4 phases, with 90 different respondents, took place between June 2017 and December 2018.

Each of the interview phases was guided by a specific purpose. In the first phase, Tool Design interviews supported the initial development of a visualisation tool. After this, a second set of interviews ['Tool Pilot'] explored how respondents reacted to the tool and how they made sense, if at all, of the various visual dimensions. In the third phase, a series of mini-interviews explored the temporal experience of participants in the immediate wake of three Impact programs (October & November 2017, March 2018). This phase sought to understand what respondents did with their change commitments in the absence of the tool. Finally, the 'PPP' (Post-Programme Process) was employed to evaluate the working tool in a real-world setting, with interviews taking place over a 2-month period after an Impact programme (September 2018). All interviews were carried out after 'successful' programmes that achieved satisfaction and commitment score > 4.7/5. The logic for this was to establish the best possible circumstances for the practising of change commitments.

Formal interview data was supplemented by ongoing participant observation. My longstanding relationship with Forum gave me the opportunity to observe the company and its employees in intimate detail. Between late 2007 and September 2018 (the release of a final working tool), I led 49 learning programmes, all located within Forum's global headquarters. Over this period, I spent close to a year of my life (355 days) at Forum; each of these days represented a 24-hour experience. The office where I worked was part of an interconnected city complex, which included a dedicated company hotel where I stayed on each visit. This meant that I literally 'lived' at Forum - I slept within the complex, had breakfast at the restaurant, shopped at their convenience store, exercised in the company gym and had dinner in-house. The nature of my day-to-day working arrangement meant that I was situated amid the office environment where I could see first-hand how employees engaged, interacted and operated. In total, over 5000 written artefacts, in various forms, were generated between 2007 and 2024. Notes were used primarily to capture information 'in-flight' (Pettigrew, 1990) as well as to facilitate reflection (Maharaj, 2016) and reflexivity (Thompson, 2014) after-the-fact. Many of the notes had the key ingredients of a learning cycle (Dewey, 1910; Kolb & Fry, 1974; Lewin, 1946) but also, vitally, acted as a pressure valve for feelings and emotions at multiple moments across the study. As a practising researcher, I was located in the unfolding flow of activity (Hussenot & Missonier, 2016) capturing 'reality in flight' (Pettigrew, 1990). My role as a semi-insider, often wearing different 'hats' at the same time, meant that complex issues of ethics and risk were often woven into the fabric of daily engagements. Note-taking became central to making sense of these unfolding situations and gave solidity to the relational backstory of the research.

The study also offered opportunities to collect a range of natural artefacts as part of my day-to-day activity at Forum. These were used to triangulate the results from formal capture methods (e.g. electronic diary screenshots, e-mail communication, photos).

Data Analysis

The study's analytical framework involved a modified form of Process Tracing (Hall, 2013; Ricks & Liu, 2018) that operated in-the-flow, over time and after-the-fact. In its purest form, Process Tracing is built around two key features (Collier, 2011): 'static' descriptions of an event/situation at a particular point in time, alongside unfolding understandings of how these static moments develop over time.

Static and sequential analysis were interlinked over the course of the study. As static analysis occurred, a picture emerged of the level of understanding at a particular point in time. This understanding was recycled via the use of 'learning moments' into the next stage of the study (e.g. a new understanding about a process would lead to a potential change in the process and hopefully increased understanding and better use). Tracing was employed as the cumulative process of vertical and horizontal analysis. Vertical analysis involved static thematic analysis, while horizontal analysis captured the growth of understanding and use over time.

The research design, by necessity, sought to incorporate differing ontological and epistemological perspectives. My worldview might best be described as a tension between Constructionist, Critical and Interpretivist strands (Norwich, 2020). Despite a strong professional background in quantitative design, I have migrated in later life to a more qualitative disposition. This methodological character, however, was not the only lens relevant to the study. The pursuit of use-inspired research meant the worldview of others was also crucial to mutual sense-making (Tickle et al., 2013). The respondents at Forum were steeped in a technical culture that valued perceived objectivity, certainty and hard 'facts'. Quantitative data and modes of understanding sat credibly within this technical/rational lens (Kinsella, 2007). In this sense, they warmed to the use of a quantitative tool, something that simultaneously respected but also challenged, through its output, their worldview (Udwadia, 1986) [e.g. 'I like that you are using hard data...but this (image) is really strange'].

Initially (2013-2017), the study was positioned as Mixed Methods Action Research (Ivankova, 2014) with simultaneous quantitative-QUALITATIVE strands (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2008). By early 2017, I had become uncomfortable with this description. The approach felt overly formulaic. In practice, I was spending a disproportionate amount of time fitting my research experiences into, what seemed like, an unrealistic design framework. Most of all, the design appeared unduly rigid to do justice to the flowing, unfolding nature of the underlying processes. As a process design emerged, I recognised that a combination of Action Research and Process was a more viable option (Luscher et al., 2006). This led to the 'final' description as a 'Process study with an action orientation'.

The base case profile: what participants normally do after a programme

Before the tool could be employed, it was necessary to establish the base-case profile, e.g. how successful were participants at currently applying their commitments without the tool? Under the existing system, three external coaches, each with a strong professional reputation, provided up to three sessions per person to support the implementation of post-programmed commitments. The take-up on this offering - despite strong endorsement from Forum Management - was consistently low. On average, 25% of participants participated in Session 1, declining to 0% in Session 3. Different coaches and approaches were employed, but there was no meaningful change in the results, e.g. low take-up on support seemed to indicate that strong intentionality to practice died off after the return to the workplace. To test this belief, it was first necessary to establish a base-case profile of the satisfaction with practising - this could then be compared to a similar score after the use of the tool to see if there was any meaningful difference.