Acknowledgements

This working paper was written during a 1-month residence at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study under the "Paris IAS Ideas" program.

1. Motivation

We often use mental shortcuts to process others' behaviors and appearances, which can inadvertently privilege certain social profiles while disadvantaging others. This systematic deviation—where individuals or groups are treated unequally based on perceived group traits rather than individual merit—is at the core of what we define as discrimination. Discriminatory behavior can stem from multiple sources, including sociocultural norms, individual experiences, and heuristic processing (Aigner & Cain, 1977; Arrow, 1973; Phelps, 1972; Schwab, 1986).

In this paper, we focus on two central sources of discrimination: beliefs and preferences. Belief-based or statistical discrimination (SD) emerges from asymmetries in information, where individuals use group averages as proxies to assess an individual's likely behavior or productivity (Arrow, 1973; Fang & Moro, 2011; Patty & Penn, 2022). Preference-based discrimination (PbD), by contrast, is rooted in animus, in-group favoritism, or psychological discomfort, leading to decisions that reflect a taste for or against particular groups (Becker, 1971; Klumpp & Su, 2013; Wozniak & MacNeill, 2015).

A growing body of experimental literature has demonstrated how these forms of discrimination operate in real-world domains, including housing (Ghekiere et al., 2022; Hanson & Hawley, 2014), hiring (Barron et al., 2024; Bohren et al., 2023; Coffman et al., 2021), and access to social capital (Dickinson & Oaxaca, 2009; Thijssen, 2021; Rissing & Castilla, 2014). These studies show that humans frequently rely on cues such as race, gender, or past group behavior to infer others' competence or intentions—even when such inferences lack individual-level justification.

To illustrate, consider a hiring process where a manager excludes Black candidates based on historically observed trends in educational attainment, ignoring individual qualifications. This is a clear example of statistical discrimination—where a probabilistic belief substitutes for individual assessment (Bohren et al., 2023; Barron et al., 2024). In contrast, if the same manager rejects candidates simply due to personal discomfort with a racial group, irrespective of their merits, this reflects preference-based discrimination (Becker, 1971). Both forms can co-exist and produce inequitable outcomes (Fang & Moro, 2011; Wozniak & MacNeill, 2015).

Our study builds on Bohren et al.'s (2023) theoretical model, which distinguishes SD from PbD by exploiting the distinction between observed outcomes and evaluative criteria. In their framework, SD arises when decisions are shaped by expectations about group-level behavior, while PbD reflects a divergence in how similar behavior is evaluated depending on group identity. This distinction is empirically tractable in experimental settings that manipulate uncertainty and information1.

We examine these mechanisms in post-conflict Colombia, where social cleavages between victims, non-victims, and ex-combatants persist despite formal peace processes. While past research has shown that exposure to violence can foster prosocial behaviors and forgiveness (Blattman, 2009; Bauer et al., 2016; Gilligan et al., 2014; Voors et al., 2012), it remains unclear how group identity shapes cooperative behavior in such polarized settings. Previous studies suggest that non-victims may harbor stronger discriminatory attitudes towards ex-combatants than victims do, yet the psychological mechanisms remain underexplored (Fatas & Restrepo-Plaza, 2024; Restrepo-Plaza & Fatas, 2022; Murillo Orejuela & Restrepo-Plaza, 2021; Unfried et al., 2022; Restrepo Plaza, 2019).

Our experimental design uses a two-stage linear public goods game involving unconditional and conditional contribution tasks. In the first (unconditional) stage, participants decide how much to contribute to a shared account without knowing their partner's behavior—forcing them to rely on beliefs or biases. In the second (conditional) stage, they specify how much they would contribute contingent on all possible partner contributions, eliminating strategic uncertainty and isolating their preference structure. The participants were SENA students, who self-identified as victims, non-victims, or ex-combatants—groups officially recognized by Colombia's transitional justice framework. This real-world identification allows us to map discrimination onto ecologically valid group divisions.

We estimate individuals' implicit beliefs about partner contributions based on their conditional responses and compare them to actual choices in the unconditional game. Discrepancies between expected and actual cooperation are used to decompose observed discrimination into SD and PbD. If an individual expects lower cooperation from a group and acts accordingly, this reflects SD. If, however, their actions diverge from expectations—either penalizing or favoring a group despite similar expectations—this reflects PbD.

Our results indicate that belief-based and preference-based discrimination follow distinct patterns. Both victims and non-victims hold beliefs about other groups' cooperativeness, but these beliefs do not fully account for behavioral differences. For instance, victims hold more pessimistic expectations about ex-combatants than non-victims (p < 0.0001), yet their behavior is more inclusive. This suggests that while beliefs matter, preferences—possibly rooted in empathy or shared experience—play a stronger role in mitigating discriminatory action. Conversely, non-victims exhibit high levels of PbD, particularly against victims and ex-combatants.

Specifically, we find that non-victims discriminate against victims, but the reverse is not observed. Specifically, non-victims exhibit a positive statistical discrimination (SD) of 69.0 against victims, whereas victims display a significantly negative SD of —302.0 toward non-victims. This asymmetry suggests that victims may hold more optimistic expectations about non-victims than vice versa. Regarding ex-combatants, both groups show similarly high levels of SD (1608.8 for non-victims vs. 1693.2 for victims), indicating that both tend to expect lower contributions from this group. At first glance, this pattern might be interpreted as reflecting more favorable beliefs about one's ingroup compared to ex-combatants, in line with social identity mechanisms (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000; Fang & Moro, 2011). However, the data do not support this interpretation: participants' implicit beliefs about the contributions of their ingroup and outgroup are statistically indistinguishable. This aligns with findings in recent experimental studies suggesting that discrimination is not always explained by differences in beliefs, but rather by how those beliefs are acted upon (Bohren et al., 2023; Barron et al., 2024).

When we examine preference-based discrimination (PbD), a contrasting and more pronounced narrative emerges. Despite their pessimistic beliefs, victims exhibit significantly lower PbD against non-victims (—959.1) than non-victims do against victims (1861.7), highlighting a greater degree of behavioral inclusivity among victims. Moreover, non-victims' PbD against ex-combatants (3528.9) is nearly three times higher than that of victims (1226.8), reinforcing the idea that discriminatory behavior by non-victims is predominantly driven by preferences rather than beliefs. These findings echo similar asymmetries observed in post-conflict societies, where victimized groups have demonstrated greater prosociality and forgiveness (Blattman, 2009; Bauer et al., 2016; Voors et al., 2012). They also resonate with lab-based evidence that preference-based discrimination can persist even when beliefs or information are held constant (Wozniak & MacNeill, 2015; Coffman et al., 2021).

These results indicate that victims, though disadvantaged and holding cautious expectations, are less likely to act on those beliefs in exclusionary ways. PbD thus emerges as the dominant mechanism of intergroup discrimination across the three groups, and victims as the group with the most inclusive behavioral profile. This distinction is important for policy and reconciliation interventions: changing beliefs alone may be insufficient if underlying preferences—rooted in identity, norms, or past grievances—are the main drivers of exclusion (Restrepo-Plaza & Fatas, 2022; Patty & Penn, 2022). The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 outlines our experimental methodology and the decomposition strategy used to isolate SD and PbD. Section 3 presents the experimental design and details of the sample. Section 4 reports the main results, including group-level comparisons and regression analyses. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the policy implications and avenues for future research.

2. The Decomposition Method

Behavioral studies isolating the role of beliefs in discriminatory behavior are common and have largely relied on curriculum vitae (CV) and rental application experiments, where researchers manipulate applicant characteristics such as gender, race, or cultural background, while holding qualifications constant (see Lippens et al., 2023; Schaerer et al., 2023, for two recent meta-analyses). These designs aim to attenuate information asymmetries and thereby isolate statistical discrimination (SD): if discrimination decreases as information increases, the residual is assumed to stem from inaccurate or incomplete beliefs.

While this approach is powerful and informative, it implicitly assumes that adding information sufficiently narrows belief gaps, thus reducing SD and revealing preference-based discrimination (PbD) as the residual. However, such assumptions neglect the fact that information processing is itself biased (Bohren et al., 2023; Patty & Penn, 2022), and that beliefs may not converge even in the presence of complete information. Furthermore, the approach positions SD as the "active" component and PbD as the "leftover," which underplays the autonomy and behavioral significance of preferences.

We propose a complementary strategy that inverts this logic: we begin by isolating PbD and use it to infer SD. In our framework, preference-based discrimination is not the residual but the baseline deviation from belief-driven behavior. This distinction is particularly relevant in social dilemmas, where cooperation decisions may be driven both by expectations (beliefs) and by normative attitudes toward group identities.

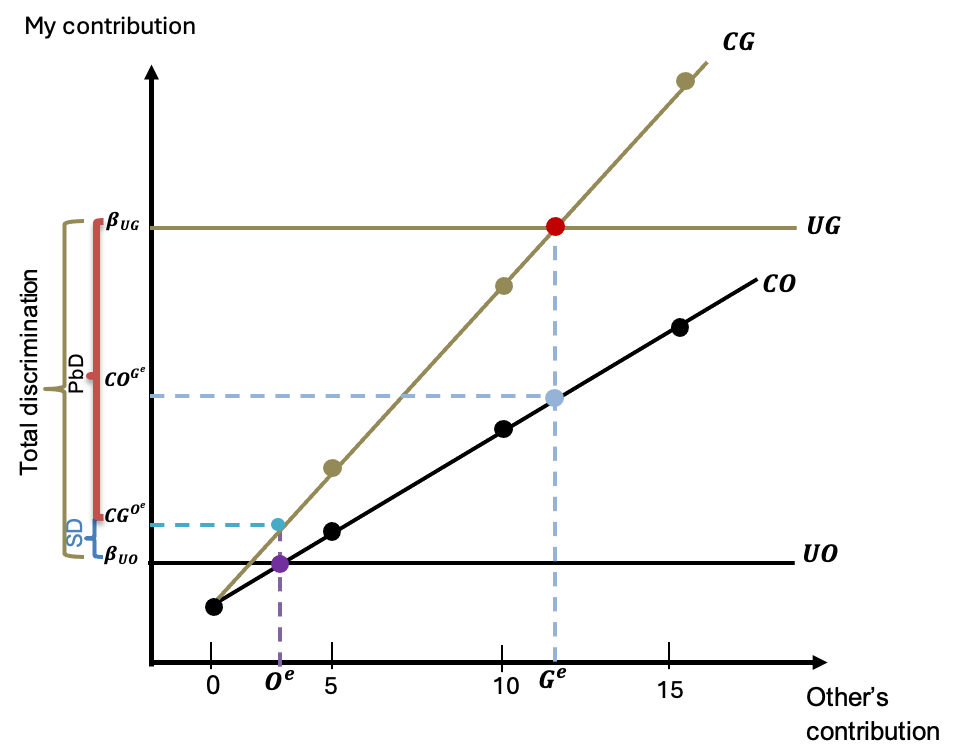

In essence, our method proceeds as follows (see Figure 1 for visual reference):

- We obtain Ge and Oe which are the subjects' implicit beliefs about an ingroup and an outgroup partner's behavior, respectively. Geometrically, these are the intersection points between the subject's unconditional cooperation (UC) level and their conditional cooperation (CC) strategy. From a behavioral perspective, Ge and Oe reflect the contributions that participants implicitly anticipate from each group, absent direct information.

- Next, we compute the conditional cooperation that would be displayed towards an ingroup partner if that partner were expected to behave like an outgroup member. Formally, we calculate, CG^(Oe)^, which is the contribution on the subject's ingroup CC curve evaluated at Oe. Geometrically, this corresponds to projecting the outgroup belief Oe onto the ingroup CC function (represented by the dashed purple line in Figure 1). Behaviorally, this captures how much a participant would be willing to cooperate with an ingroup partner who they expect to act like an outgroup partner.

- We define statistical discrimination (SD) as the difference between the conditional cooperation with an ingroup partner expected to behave as an outgroup member CG^(Oe)^, and the unconditional cooperation actually shown towards an outgroup member. In behavioral terms, this comparison controls for expectations (both equal to Oe) and isolates the impact of group identity on behavior: it is a within-subject measure of how differently individuals act toward identical behaviors depending on the partner's group membership.

- We compute the PbD as the difference between total discrimination (TD), and SD.

This allows us to decompose overall discrimination into a belief-driven and a preference-driven component, with PbD emerging as a direct behavioral deviation not attributable to differences in expected partner behavior.

This decomposition has both methodological and substantive implications. Methodologically, it avoids reliance on exogenous information treatments and instead uses participants' revealed expectations to operationalize beliefs. Substantively, it offers a framework to detect asymmetric sensitivity to group identities even when expectations are held constant, consistent with growing evidence on affective and moral foundations of discrimination (Coffman et al., 2021; Restrepo-Plaza & Fatas, 2022).

Figure 1. Theoretical Representation of Statistical and Preference-Based Discrimination

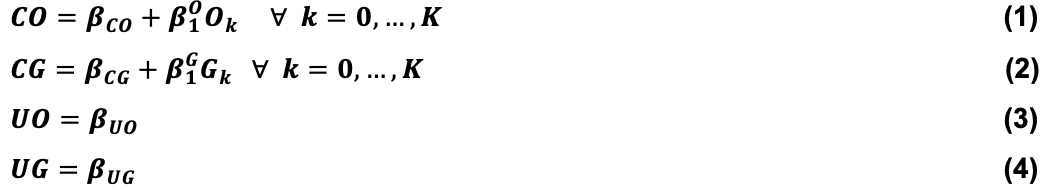

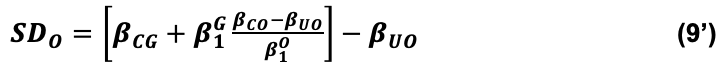

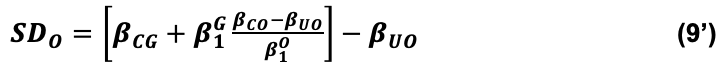

Formally, the procedure looks like the following:

Let the unconditional and conditional cooperation behaviors toward ingroup and outgroup partners follow a linear relationship with respect to the partner's contribution. This assumption, while simplifying the analysis, does not entail a loss of generality: the same logic and estimation procedure can be extended to higher-order (e.g., polynomial) functional forms. However, the linear specification allows for more intuitive geometric interpretations and underscores the conceptual clarity and tractability of the decomposition exercise.

Let CG and CO represent the conditional cooperation functions towards the ingroup and the outgroup, respectively, and in the same line, UG and UO the unconditional cooperation functions. UO and UG are constant parameters that represent the part of the contribution that is not contingent on the partner allocation to the group account, but it is inheritably determined by their willingness to cooperate. In contrast, β_1^G^ GK and β_1^O^ OK represent the slope parameters of the conditional cooperation functions i.e. the best response to any of the partner contributions. Notice that, due to their unconditionality, UG and UO are flat in our Cartesian representation, meaning that they remain constant to all possible partner allocations.

First step:

Implicit beliefs are derived by determining the partner contribution at the intersection of the conditional and unconditional cooperation functions, specifically equations (1) and (3) for the outgroup, and equations (2) and (4) for the ingroup. At these points, which we call Ge and O^e)^, participants are allocating to the group account some amount that might be consistent with what they expect the partner will contribute. This decision is unconditional in nature, as they cannot make a strategy plan in advance. However, it does possess a certain degree of conditionality, as it is influenced by the participant's beliefs about their partner's behavior.

Equalizing (1) and (3) we obtain:

Assuming Ok = Oe,

Likewise,

Second step:

Intergroup discrimination is determined by differences in behavior when interacting with an ingroup or an outgroup. In the second step, we go back to the original conditional cooperation equations, (1) and (2), to compute the decision-maker response to the values obtained in (5') and (6'), correspondingly. The sequence of heuristics looks like the following:

(5') in (2)

(6') in (1)

Third step:

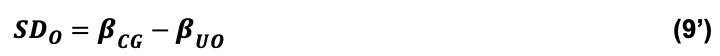

This step yields the measure of statistical discrimination (SD) exhibited by an individual when interacting with an outgroup member. Since SD is driven by the subject's beliefs about the expected behavior of the partner, the first term in equation (9) captures the participant's conditional cooperation response to an ingroup member whose behavior is known to match the expected behavior of the outgroup (i.e., a "belief-controlled" benchmark). In contrast, the second term reflects the unconditional cooperation extended to an outgroup member, whose behavior is uncertain and inferred through prior expectations. The difference between these two responses—ingroup with known behavior versus outgroup with expected behavior—encapsulates the essence of statistical discrimination: the behavioral gap that emerges solely from differences in how beliefs are formed and applied depending on group identity.

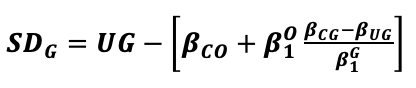

Intuitively, equation (9) allows us to assess whether participants are more cooperative toward an ingroup member whose contribution matches what they expect from an outgroup. In essence, it isolates whether group identity alone affects behavior when expectations are held constant. Additionally, a complementary and mathematically equivalent approach (see Annex 1 for formal proof) is to evaluate whether participants behave less cooperatively with an outgroup member whose contribution aligns with their expectations for the ingroup. Both formulations capture the same behavioral asymmetry—namely, the differential treatment of identical contributions depending solely on the social identity of the partner—which lies at the core of statistical discrimination. SD_G in equation (10) assesses whether expectations towards the ingroup affect individuals' behavior.

Fourth step:

In this final step, we compute preference-based discrimination (PbD) as the residual difference between total discrimination (TD) and statistical discrimination (SD). As illustrated in Figure 1 and formalized in equation (11), TD is defined as the difference between the subject's unconditional cooperation toward an ingroup versus an outgroup partner. Because unconditional cooperation reflects a combination of elements—including beliefs about the partner's behavior, intergroup attitudes, and the individual's baseline prosociality—the resulting intergroup gap encapsulates both belief-driven and preference-driven components. By subtracting SD from TD, we isolate the portion of discriminatory behavior that cannot be explained by differences in expectations and is thus attributable to group-based preference biases. This residual, formalized in equation (12), constitutes our measure of PbD.

3. The Behavioral Task

We implemented a linear public goods game (PGG) to elicit participants' willingness to cooperate with partners from different social groups. The experimental sessions were conducted in partnership with the National Learning Service of Colombia (SENA), a large public vocational education and training institution with a national mandate to serve vulnerable populations, including individuals affected by armed conflict. Because SENA's enrollment procedures require applicants to self-report their vulnerability status—including whether they are registered victims of the conflict or demobilized ex-combatants—our sampling frame allowed for an ecologically valid categorization of participants into three groups: victims (V), vulnerable non-victims (Non-V), and ex-combatants (ExC).

This natural group structure enabled us to examine intergroup decision-making patterns grounded in lived social identities. The behavioral task consisted of two main components:

- Unconditional cooperation: Each participant made three independent contribution decisions to a joint account, without knowing their partner's identity or behavior. Each decision was framed as a potential match with a randomly assigned partner from one of the three groups (V, Non-V, ExC), allowing us to observe baseline cooperative tendencies toward each group in the absence of strategic feedback.

- Conditional cooperation: Participants were then asked to complete a strategy method table, indicating how much they would contribute to the group account for every possible contribution level (ranging from 0 to 15,000 COP in 5,000 COP increments) by their partner. This was done separately for potential partners from each group. These responses allowed us to trace the conditional cooperation function and infer implicit expectations about partner behavior.

Because our sample included partners with varying degrees of social distance, we classified group pairings as follows:

- Ingroup interactions: V/V and Non-V/Non-V matches.

- Other ingroup interactions: V matched with Non-V and vice versa.

- Outgroup interactions: Any match involving an ExC partner (i.e., V/ExC and Non-V/ExC).

We interpret discriminatory behavior as any systematic deviation in cooperation levels toward other ingroup or outgroup partners relative to one's own ingroup.

All contribution decisions ranged from 0 to 15,000 COP (approximately USD $4 at the time of implementation), in increments of 5,000 COP. Contributions placed in the group account were multiplied by a marginal per capita return of 1.4 and evenly distributed between the two group members, regardless of individual contributions.

The sessions were conducted in 2018 using paper-and-pencil protocols at SENA facilities. We collected a total of 193 observations: 71 from victims, 115 from non-victims, and 7 from ex-combatants. Although the number of participating ex-combatants was relatively small, their inclusion was sufficient to maintain the credibility of the matching process and ensure that participants perceived a non-negligible probability of being paired with a member of any group type.

4. Results

4.1. Contributions to the Group Account and Implicit Beliefs

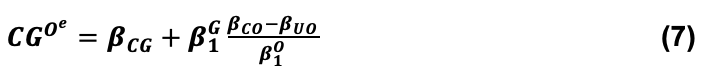

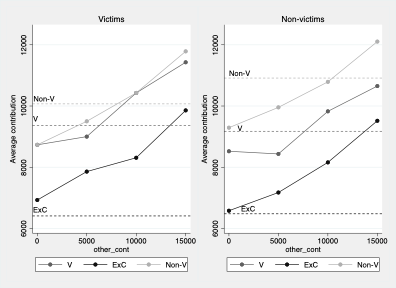

Given that we only have seven observations from ex-combatants, the results section focuses on the cooperative behavior of victims and non-victims. Figure 2 replicates the structure of Figure 1 but displays average contribution decisions by group type, rather than individual-level data. As such, the intersection points in Figure 2 do not correspond precisely to participants' implicit beliefs, but rather illustrate aggregate trends.

The upward slopes of the solid lines in both panels suggest that, on average, both victims and non-victims adjust their contributions positively in response to increases in their partner's contribution—regardless of the partner's group identity—consistent with reciprocal behavioral tendencies.

The vertical distances between the solid (conditional) and dashed (unconditional) lines across target groups reflect intergroup preference patterns. In the left panel (victims), the dark and light gray lines—corresponding to contributions toward ingroup and other ingroup members, respectively—are nearly indistinguishable, indicating that victims tend to treat non-victims as they would treat members of their own group. This inclusive pattern is not mirrored by non-victims (right panel), who display significantly lower contributions toward victims compared to their own group, as confirmed by t-tests across all conditional contribution levels (p-value < 0.0001).

Moreover, both groups exhibit lower cooperation toward ex-combatants relative to their ingroup, consistent with outgroup discrimination. However, this discrimination is significantly more pronounced among non-victims than among victims (p-value < 0.05). These findings replicate and extend previous evidence reported by Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022) and underscore the asymmetry in intergroup cooperation depending on the participant's social identity.

Figure 2 Individual Contributions to the Group Account

Note: the linear graphs represent the average response at each partner contribution. Dashed and solid lines represent the unconditional and conditional cooperation decisions, respectively, when matched with an ex-combatant (black), a victim (dark gray) or a non-victim (light gray).

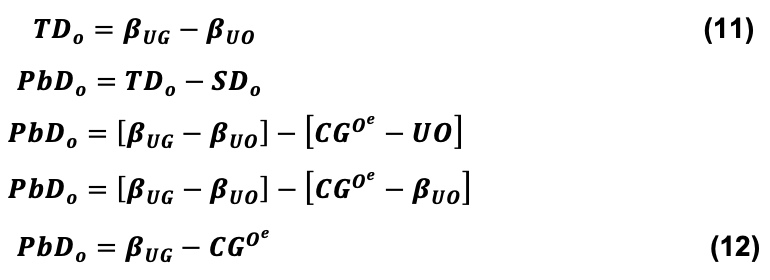

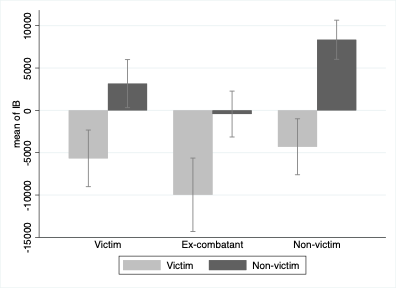

Figure 3 presents the average implicit beliefs inferred from participants' unconditional cooperation decisions, as estimated through individual-level model parameters. These beliefs occasionally take negative values, indicating pessimistic expectations regarding the partner's contribution.

Among victims, implicit beliefs are consistently negative across all partner types: fellow victims (—5,668.6 COP), non-victims (—4,301.1 COP), and ex-combatants (—9,968.3 COP). However, these differences are not statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05), suggesting that victims anticipate similarly low contributions regardless of group identity. Notably, victims' beliefs are significantly more pessimistic than those held by non-victims across all target groups (p-values < 0.001), highlighting a generalized expectation of low cooperation that is unique to this group.

In contrast, non-victims exhibit more optimistic expectations overall. Their implicit beliefs are positive toward victims (3,156.0 COP) and slightly negative toward ex-combatants (—434.8 COP), yet both values are significantly lower than their expectations toward fellow non-victims (p-values < 0.05). Furthermore, the difference between their beliefs about victims and ex-combatants is statistically significant under a one-sided t-test (p-value = 0.0368), indicating that non-victims differentiate more clearly between these two groups.

Taken together, these patterns suggest contrasting psychological foundations across groups. If behavior is primarily belief-driven, we would expect victims—who hold uniformly pessimistic expectations—to exhibit stronger discriminatory patterns in subsequent decisions. Conversely, if preferences (rather than beliefs) are the main driver of discriminatory behavior, the more salient differentiation observed among non-victims may lead them to exhibit greater discrimination in the next stage of analysis.

Figure 3 Estimated Implicit Beliefs by Type

Note: Figure 3 illustrates the averages and standard deviations of the estimated implicit beliefs regarding the behavior of victims, ex-combatants, and non-victims. The light gray bars represent victims, while the dark gray bars represent non-victims.

4.2. Total, Preference-based and Statistical Discrimination

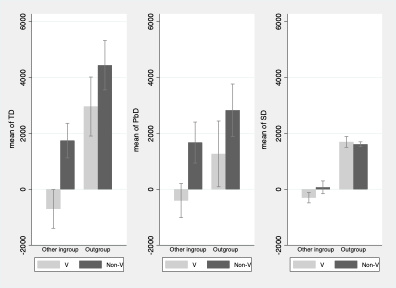

To produce the results presented in Figure 4, we applied the four-step procedure outlined in Sections 2 and 3 to estimate total discrimination (TD), statistical discrimination (SD), and preference-based discrimination (PbD). Following Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022), TD was calculated as the difference between a participant's unconditional contribution toward an ingroup member and their contribution toward an outgroup or other ingroup member.

To estimate implicit beliefs, we first obtained the parameters of equations (1) and (2) by fitting a censored Tobit model to participants' conditional cooperation decisions as a function of the partner's contribution level to the public good. These models account for the lower and upper bounds of the contribution scale and capture individual responsiveness to partner behavior.

Next, we inferred each participant's implicit belief about the partner's expected contribution by solving the estimated conditional cooperation equation for the value at which it equals the observed unconditional contribution. That is, we identified the partner contribution level that would rationalize the subject's unconditional behavior under the estimated conditional strategy—our measure of Ge or Oe, depending on the group.

To compute SD, we re-inserted the implicit belief about the outgroup's expected behavior (Oe) into the conditional cooperation function estimated for the ingroup. This gave us the participant's predicted contribution toward an ingroup partner behaving like an outgroup member. We then subtracted the observed unconditional contribution toward the outgroup. The resulting difference isolates statistical discrimination: the extent to which behavior diverges when expectations are held constant but group identity differs.

Finally, we computed PbD as the difference between TD and SD.

Figure 4 Total, Preference-based and Statistical Discrimination from Victims and Non-Victims against the other ingroup and the outgroup

Note: from left to right, Figure 4 illustrates the averages and standard deviations of the total discrimination (TD), preference-based discrimination (Pbd), and statistical discrimination (SD) against the other ingroup and the outgroup. The light gray bars represent victims, while the dark gray bars represent non-victims.

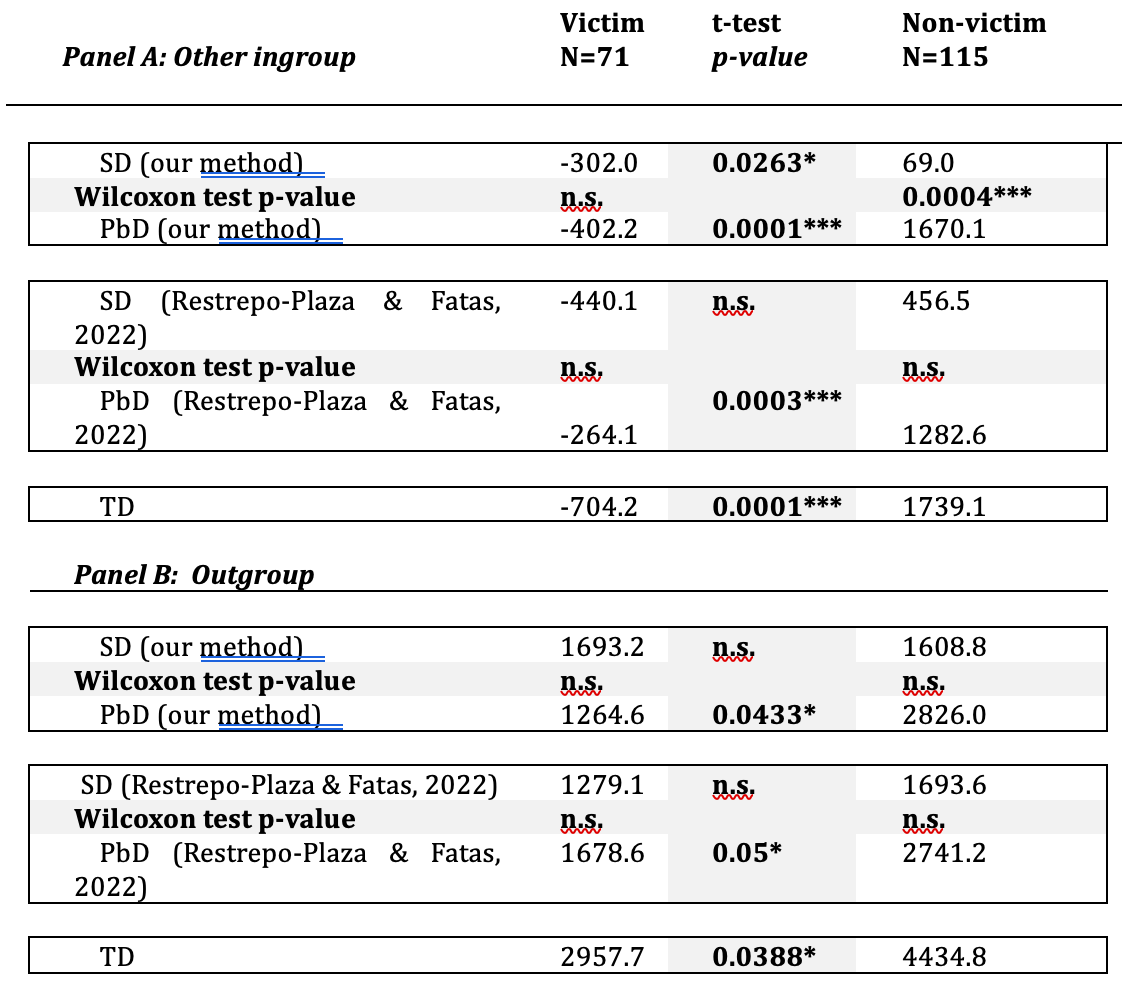

Our findings reveal that both preference-based discrimination (PbD: 1,670.13 vs. —402.2, p-value < 0.001) and statistical discrimination (SD: 69.0 vs. —302.0, p-value < 0.05) toward the other ingroup are significantly higher among non-victims than among victims, indicating asymmetrical levels of animosity across groups. Interestingly, while non-victims exhibit clear exclusionary behavior toward victims, the latter appear to positively discriminate in favor of non-victims. This pattern aligns with the stigma reversal hypothesis proposed by Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022), suggesting that group preferences, rather than beliefs alone, may be shaping cooperative behavior.

In their study, Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022) suggested that there are not significant differences between SD and PbD toward the other ingroup across victims and non-victims, which they interpreted as evidence of comparable weights of beliefs and preferences in intergroup dynamics. However, our results add nuance to that conclusion. As shown in Table 1, for victims, the paired comparison between PbD and SD in their discrimination toward non-victims is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.4507). In contrast, for non-victims, the difference is both statistically significant (p-value < 0.0004) and substantively large (1,670.1 vs. 69.0), leading us to conclude that their discriminatory behavior toward victims is primarily driven by group-based preferences rather than expectations.

Our approach also mirrors the findings of Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022) in the context of discrimination against ex-combatants. First, both PbD and SD against ex-combatants are significantly greater than those observed toward the other ingroup (p-value < 0.05 in all comparisons), reinforcing the outgroup status of ex-combatants. Second, as shown in Table 1, neither our method nor that of Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas finds significant differences between SD and PbD in discrimination against ex-combatants, suggesting that both beliefs and preferences contribute equally to the observed exclusion.

Third, and perhaps most strikingly, while SD toward ex-combatants is comparable across victims and non-victims, the level of PbD is significantly lower among victims. This result supports the shared-victimhood hypothesis (Vollhardt, 2015), which argues that victims may perceive ex-combatants as fellow sufferers of the same violent context, thereby developing more inclusive attitudes toward them. This psychological mechanism—unique to victims and inaccessible to non-victims—appears to attenuate preference-based discrimination and is consistent with the interpretation advanced by Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022).

Table 1 Comparison of Restrepo-Plaza & Restrepo-Plaza & Fatas (2022) Discriminatory Measures

Note: table 1 displays the averages of the total discrimination (TD), preference-based discrimination (Pbd), and statistical discrimination (SD) from victims and non-victims against the other ingroup (panel A) and the outgroup (panel B) from. We use the t-test for comparisons between victims' and non-victims' behavior, and the Wilcoxon paired test to compare SD and PbD values within the same group.

5. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of discriminatory behavior by proposing a novel methodology to disentangle the effects of statistical discrimination (SD) and preference-based discrimination (PbD) across socially salient groups. We apply this framework to a real-world post-conflict setting—Colombia—focusing on the interactions between victims, non-victims, and ex-combatants. While grounded in a specific context, the approach and insights generated are broadly applicable to other settings where beliefs and preferences jointly shape intergroup discrimination.

Our findings yield four key contributions:

First, we provide robust evidence that PbD constitutes the predominant form of intergroup discrimination. This is particularly evident in the asymmetrical behavior between victims and non-victims: while non-victims exhibit both SD and PbD against victims, victims display inclusive behavior toward non-victims. These patterns support the stigma reversal hypothesis proposed by Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022), whereby victims' exposure to systemic marginalization fosters greater empathy and mitigates prejudicial responses. Similarly, both groups discriminate against ex-combatants, but non-victims display significantly stronger exclusion, consistent with the shared-victimhood hypothesis (Vollhardt, 2015), which posits that victims may perceive ex-combatants as fellow sufferers of the same conflict.

Second, our analysis of implicit beliefs reveals that victims consistently hold more pessimistic expectations about all groups—including their own—than do non-victims. These findings suggest that expectations alone cannot fully account for discriminatory behavior. Instead, preferences and deeper psychological orientations appear to play a larger role, particularly in explaining non-victims' exclusionary attitudes toward victims. This distinction reinforces the need to go beyond informational approaches when addressing discrimination.

Third, relative to previous research—including Restrepo-Plaza and Fatas (2022)—this paper contributes a methodological refinement by quantifying implicit beliefs and isolating their contribution to SD through a deductive decomposition strategy. While prior work often treated SD as a residual or relied on informational treatments, our approach models both SD and PbD explicitly, yielding more precise and behaviorally grounded estimations. Moreover, whereas previous findings suggested that SD and PbD contributed similarly to discrimination across groups, our results show that for non-victims, discriminatory behavior toward victims is primarily driven by preferences, not expectations. This refinement sharpens our theoretical understanding of how social identities and post-conflict experiences shape exclusion.

Fourth, from a policy standpoint, these findings suggest that reducing discriminatory behavior in post-conflict settings requires more than correcting misperceptions or asymmetries of information. While belief-targeted interventions (e.g., awareness campaigns or transparency tools) remain useful, they may have limited impact unless paired with efforts to reshape group-based preferences. Programs that promote meaningful intergroup contact, encourage inclusive narratives of victimhood, and acknowledge the legitimacy of different conflict experiences may help reduce PbD and promote social cohesion.

In sum, this study contributes to the broader literature on discrimination and post-conflict reconciliation by empirically demonstrating the importance of distinguishing between beliefs and preferences in shaping intergroup behavior. Future research should explore how conflict exposure interacts with psychological dispositions over time, and whether targeted interventions can sustainably shift both expectations and preferences in divided societies.

Annexes

(3) in (9)

(7) in (9')

Let's assume that the subject*'s* unconditional contribution is the same than their conditional contribution if the partner contributes zero, i.e., β_CO = β_UO. Then, equation (9') will look like:

If individuals are to behave better with the ingroup than with the outgroup, keeping the contributions fixed in the outgroup's expected behavior, that should be equivalent to behave worse with an outgroup that contributes what they expect from the ingroup. Formally, that is:

(8) in (10)

If β_CG = β_UG

(3) in (10')

- Bohern et al. (2023) also suggest that decision-makers' responses depend on the partner's signal precision and the belief accuracy. However, we do not account for these elements in our study, as the task we use to compute implicit beliefs involves no uncertainty regarding the signal and does not allow for signal imprecisions. Furthermore, we depart from the authors in their differentiation between accurate and inaccurate beliefs regarding partner behavior. This distinction is not relevant to our paper, as our focus is on the effect of people's beliefs on intergroup preferences, regardless of their accuracy.Annexes↩