Acknowledgements

This paper was written during a 1-month residence at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study under the "Paris IAS Ideas" program.

"Progress only begins where it ends".

Theodor Adorno

I would like to start by saying that one of the most structuring features of our time is the scale of our crises. We have a system of "related crises" that doesn't seem to be going away (Gabriel et al., 2022). By related crises we mean the deep connection between ecological, social, political, economic, demographic, and psychological crises that seems to have stabilised globally. And I would like to start by insisting on this seemingly paradoxical theme, namely crises that stabilise as crises. For everything is happening as if we were facing crises that have become the normal regime of government, such as the long political crisis of the institutions of liberal democracy over the last twenty years, or the long economic crisis that has been on the horizon since 2008 to justify the economic policies of our countries and institutions (Streeck, 2014). These crises have not prevented the preservation of the foundations of neo-liberal economic management, nor the deepening of its logic of concentration and silencing of social struggles. On the contrary, we could even say that they have provided the ideal soil for these processes to take place.

This dynamic of normalising crises raises profound questions about the strategies of critical thinking. It points to a mutation in our forms of governance, as these can increasingly normalise the use of exceptional and authoritarian measures within social management processes. It also points to a structural retraction of the horizons of transformation capable of driving the imagination towards other forms of social relations. However, it is precisely at this moment of retreat that we see more and more doubts about the effective commitment of critical theory to structural transformations in capitalist society, to listening to the real extent of the suffering immanent in its forms of social domination, to the point where some speak of an inescapable process of "domestication" of critique (Kouvélakis, 2019). A domestication that results from its adaptation to the limited horizon of social conflicts that can be managed by the institutional structure currently operating in the countries of central capitalism. A horizon that is increasingly showing its unreality and its natural link to the restoration of the dynamics of primitive accumulation, which the European continent only briefly controlled after the Second World War, thanks to the strength of the system of proletarian struggles, which no longer exists.

From this point, I would like to insist that part of the paralysis that afflicts us comes from the inability to understand that this system of related crises has at its foundation a deeper crisis, namely an epistemic one. The engagement of subjects in processes of social struggle is not necessarily linked to the suffering and precariousness to which they are subjected. Subjects and populations can endure extremely high levels of suffering if they are unable to see themselves as potential agents of transformation. This potential requires not only effective forms of political organisation and solidarity building. It also requires a re-dimensioning of the social imagination, a certain capacity to realise relationships and processes that previously seemed impossible.

This paralysis of the social imagination is largely related to what we might call epistemic crises. By epistemic crisis we mean a crisis in what we might call "the condition of possibility of all possible experience". Our social experience, with its forms of categorisation, distinction and organisation of space and time, is not a transcendental condition, but a social institution that defines the material conditions of social reproduction embodied in recurrent economic and political processes. These forms, in turn, provide what we might call a "social grammar" that determines not only the meaning of values with a strong normative potential, but also the way in which they are applied, the clarity of their semantics and, above all, the form of the subjects who can articulate them. It is this grammar that defines the limits of what is imaginable and what is not. For this reason, the impossibility of modifying this social grammar produces a system of inhibitions of action that must be analysed in its own dynamic. In fact, if there is one thing that the historical experience of the 20th century has shown us, it is that we can even modify the economic bases of our societies without actually changing this grammar, as if changing it required specific regimes of action and struggle.

Destroying Nature

I make this introduction in order to argue that one of the fundamental axes of the hegemonic social grammar of our time lies in the notion of "nature". In other words, the way we define and create "nature" determines a wide range of our modes of experience and social action. For the West is not really a form of society. It is primarily a form of nature, or if you like, a way of defining the living system that affects us and in which we participate as "nature". It is by inventing something like "nature", with its internal tensions and categories, that we have created our Western societies. Because it is the defining concept of our life-structures, albeit in opposition. For it would be a case of remembering: where nature defines the rhythm of movement, there can be no history for us. Where nature defines behaviour, there can be no self-determination. Where nature defines cycles, there can be no freedom. For this reason, a critical theory that is effectively committed to emancipation cannot leave intact the presuppositions that the concept of nature has integrated into the history of modern rationality. It must understand that it is not only our relationship to nature that is in crisis, but that nature itself is in crisis, in the sense that it is impossible to maintain what has hitherto been its social place.

This leads us to say that there is a destruction of nature that has to be done if emancipation is to be realised. This is not the physical destruction that we are seeing more and more dramatically these days, but the destruction of nature as a social horizon for action and determination, as what defines both how we should act on the environment and who and what we are. In a way, we could even say that in order to prevent the physical destruction of nature, another form of destruction of nature is needed.

There are those who, when they hear statements about nature as a social construction to be challenged and ultimately destroyed - something I share to a certain extent - immediately imagine that they are dealing with radical anti-realist thinking, which almost delusionally denies the existence of processes independent of our description and action. So much so that someone like Andreas Malm has to remind us: "To discover coal in a jungle in Borneo is to open a channel into that past [before human action] and to get hold of something that no human has helped to produce, and this is true of any fossil fuel extracted from the bowels of the planet" (Malm, 2019, p.35).

But we should remember that those who seek to carry out the political project of denying the existence of nature don't necessarily want to deny the existence of entities independent of our description, nor imagine that coal wouldn't exist without us. Rather, they try to deny our way of describing such entities because of its social and political consequences, to problematise the naming of such processes as "nature". For it is impossible to ignore the fact that "nature" is a heteroclite construction whose heteroclite structure has a clear function, namely, to create a confusing zone of overlap between science, theology, morality, politics, philosophy, and economics. What we call "nature" is something made up of various elements such as: physical processes independent of the observer, libido, instincts, DNA sequences, natural species, God, physical processes dependent on the observer (such as those raised by quantum physics), hierarchies, a certain notion of growth, Amerindian peoples, and so on. In other words, it is a social construction aimed at superimposing values and constituting a "natural" disposition to act on the environment that surrounds us and on ourselves.

The nature we are dealing with was born at a certain historical moment. It is not the physis of the Greeks, nor the urihi of the Yanomami. These are literally other worlds for us. The concept that is hegemonic for us was imposed by a profound articulation between the development of capitalism, theology-politics, and expansionist interests. And just as it was born, it can die. The childish enlightenment that consists in believing that we can and should distinguish between properly scientific statements about nature and properly "ideological" statements risks doing a disservice to critique. For "nature" as a concept and value was created precisely so that these statements could pass each other by. The emergence of the scientific view of nature as a machine, for example, is inseparable from a system of theological presuppositions that are strengthened, not weakened, by the development of modern science.1 Presuppositions that allow not only the mathematisation of physical phenomena, but also the constitution of a certain notion of human exceptionality that is fundamental to the emergence of our notions of consciousness, autonomy, and subjectivity.

It is not, then, a question of acting like those who deny the relevance of the distinction between nature and culture, like those who preach its obsolescence.2 In fact, the distinction is more relevant than ever. In order to operate its logic of extraction and its illusion of progress, capitalist society needs to define what nature is, to distinguish itself from it. At a second moment, when the catastrophic consequences of this distinction become evident through the crises we know today, it becomes necessary to "anticipate reconciliation", to place it as already achieved within the framework of capitalism. But it would be a case of insisting that the nature/culture distinction is not a misunderstanding of modernity. It is a fundamental assumption of our mode of production. It is repeated daily in every process of capitalist production.

However, we must recognise the political task of overcoming this dichotomy. It's no coincidence, as we will see later, that we have to pay attention to the way in which the social struggles led by people who have been excluded and opposed to the process of "capitalist modernisation" (people who have therefore refused to make a strict distinction between nature and culture) have the possibility of setting in motion real processes of politicising the end of nature. This end appears as an important moment in a project of social emancipation.

These struggles remind us of how the social place of nature has led us today to make explicit the violence inherent in the values that for centuries seemed to guarantee the paths to our emancipation and freedom, to the deepest realisation of our potential to be ourselves. Progress, development, abundance, wealth, growth: these concepts are charged with a profound normative dimension, because they seem to guarantee the material conditions for emancipation. And all these concepts, which are currently being questioned because of the crises and violence they have generated, are deeply linked to the fate we have so far given to nature, to our understanding of the kind of relationship we should have with it, to the distance we should keep from it. In this sense, I can only agree with Pierre Charbonnier, who reminded us in a beautiful book:

"The meaning we give to freedom and the means we use to establish and maintain it are not abstract constructions, but the products of a material history in which the soil and the subsoil, the machines and the properties of living beings have provided decisive levers of action. The current climate crisis is a spectacular illustration of this relationship between material wealth and the process of emancipation" (Charbonnier, 2021, p.12).

In other words, what we mean by freedom is inseparable from a set of social and economic actions aimed at guaranteeing the conditions for the exercise of our autonomy. Freedom is not a subjective disposition; it is not a predicate that we give to individuals. Rather, it is a system of social practices, a predicate of social bodies. In the case of our societies, these social practices are linked to the way we control nature, how we make it a space for the extraction of resources against the fear of scarcity, scarcity itself, and vulnerability.

Psychic Life and Theology-Politics

I would like to dwell on these issues to emphasise that this crisis in the social place of nature does not only concern a set of values that guide our socio-economic models. It also affects what we might call the "theological-political foundations" that constitute both our capitalist societies and the normative horizon of what we mean by ourselves. The crisis of nature is a crisis of the theological-political project of which it is a part. And the crisis of this longstanding theological-political project profoundly affects a certain hegemonic notion of autonomy and freedom that is ours. In other words, its crisis necessarily leads to the crisis of one of the most powerful normative concepts we know. This means that overcoming such crises doesn't just require social struggles aimed at regulating extractivism and changing relations of production. It also requires a critique of autonomy as a political horizon for emancipation, a structural reconfiguration of subjects and their social conditions for self-preservation.

So, I would like to start with two assumptions:

a) Concepts such as identity, personality, individual and autonomy are theological-political concepts. They are grounded in an area where theology and morality are intertwined. And they are political insofar as they justify operations of hierarchy, self-government, and domination.

b) The constitution of ourselves, our promises, and our pain, is inseparable from the agonistic relationship we establish with what we define as "nature". Our own theology-politics has accustomed us to the idea that we are beings traversed by conflict, by opposition, and at the root of this conflict is our dramatic relationship with nature.

This opposition will be the basis for a conception of moral autonomy as a capacity for self-legislation that still appears today as a constituent point of our conception of emancipation. But before I go any further, I would like to insist on two points. First, when we say "we" in this context, we are referring to the horizon of Christian theology. This, on the one hand, places obvious limits on the supposed universality of the processes described here. There is, however, an important element to be borne in mind. This specific theological-political basis provided to a large extent the socio-subjective conditions for the development and strengthening of capitalism. The necessary and constitutive articulations between capitalism and Christianity are a major theme of classical sociology.3 If we accept this point, then any society subjected to the dynamics of the valorisation of capital (in other words, any society that exists today) will have to deal with the tendencies towards material reproduction and the production of subjectivities that are typical of this theological model. Of course, societies will deal with these tendencies taking into account their own conflicts. But none of them will be indifferent to the horizon described in this text.

Second, we can speak of political theology in this context because it is a reflection on the structure of the exercise of power that finds its foundation in a theological conception of the will. One of the fundamental characteristics of the political theology that characterises the West is its conception of power as the exercise of a sovereign and unitary will, be it the will of the king or the will of the people. This will has its matrix in the idea of the "divine will" because of its causa sui structure, the potential immanence between being and doing. As in God, the will, when it is free will, is the cause of itself, it doesn't get confused or lost, it is the movement of actualising what never leaves itself, which is why it is the expression of a sovereign decision. There is no causality external to this will, it is not influenced from outside, but is realised as a principle immanent to itself.4

The presence of this concept of will is not only a constitutive feature of our concept of political power, of the people and of popular sovereignty. It will also be present in the constitution of the way we relate to ourselves. For we must not forget that our notion of autonomy is above all the expression of a relationship of government, of being able to govern ourselves, based on the construction of a potential unity between the self and the law that I give to myself. Giving the law to oneself is something that, at the limit, only God can do, because only in him is the immanence between nomos and ipse, between law and self, absolutely realised. But in order for this relationship between nomos and ipse to be realised, that which does not conform to this condition of causa sui must be defined as "nature" and be the object of a certain kind of relationship.

At this point I would like to add something else that may help us to understand why we should be talking about political theology here. One of the main characteristics of political theological relations is that they confuse government with the struggle against evil. Every time evil is invoked in the political arena, we can be sure that we are back to theology. Because against evil there is no negotiation, there is a fight to death, there is victory and defeat. Against evil, there is the absolute violence that is proper to theology in act. There is no secular concept of evil, it has always been and will always be a theological concept. In this sense, wherever "evil" is mobilised, not only in relation to the other, but above all in relation to oneself, we will find ourselves in relations of hierarchy and evaluation that require an operation of a political theological nature. In this way, self-government will mean fighting the evil that inhabits us or lurks within us. An evil that takes hold of us and whose best expression is disobedience. For evil has never been about cruelty and violence, not least because there is no good that doesn't allow cruelty towards those who don't believe in the good we defend. The fundamental evil will always be to ignore the necessary hierarchies.

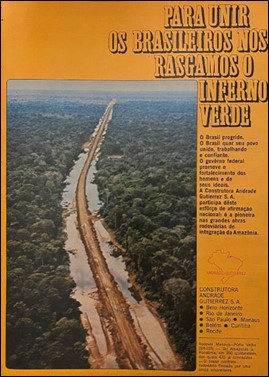

In this sense, I cannot help but recall an illustrative example for what I have in mind. We are in Brazil in the 1970s, in the midst of a wave of development promoted by the military dictatorship. One of the fundamental elements on the horizon for progress in what has always been one of the world's main frontiers for agricultural development is the connection through the Amazon rainforest. At this point, the military government decided to build a major highway that would cut the forest in half. It is called the Trans-Amazon Highway. The road will never be completed. But as part of the struggle for progress, an advertising campaign was launched that had the advantage of explicitly stating what had always been assumed. As shown in Figure 1, the campaign shows the forest cut in half by the road and the headline: "To unite Brazilians, we tear apart the green hell". Progress, the formation of the nation-state, the creation of unity is a question of overcoming the evil represented by the green hell, an evil that must be overcome, that lurks around us to prevent the realisation of human development, like a kind of "heart of darkness" wherever the light doesn't reach.

Figure 1. Advertisement Campaign in Trans-Amazon Highway in the 1970s

Note. Photo was taken by author from https://www.reddit.com/r/PropagandaPosters/comments/1bsihkv/1970s_brazilian_military_junta_poster_advertising/?rdt=62049

Saint Augustine and the Emergence of the Self

But this heart of darkness is not only in the spaces that prevent us from opening our paths. It is also within us, which is what makes this battle so decisive. In this sense, let's go back to 1607 and listen to a kind of poem written by a Puritan, George Goodwin, entitled Automachia, or the Self-Conflict of a Christian:

"I sing my self, my internal civil wars

The victories I lose and gain

The daily duel, the constant struggle

The war that never ends, until the end of my life

And yet not only mine, not only mine,

But of all those who, under the honourable banner

Of Christ's banner, uphold his name

With holy vows of body and soul" (Goodwin, 1607).

I bring up this text because it expresses something fundamental in the genesis of our notion of freedom and autonomy. Something that perhaps only a religious person can truly express. Let us note how freedom appears here as the constant exercise of an internal civil war, a struggle that never ends and that is sustained by a constitutive relationship with the divine.

We can understand the matrix of this war by looking at the theological foundations of the notion of self-identity. These foundations take us back to St Augustine, among others. Here we find one of the starting points of a long movement that will lead us to the modern concept of autonomy and the creation of the modern concept of nature. Augustine could not fail to be one of the starting points, because with him something fundamental about our writing in the first-person singular was born. Before Augustine, those who used the first-person singular never used it to speak of themselves as someone who presents a perspective which, being a perspective, can only be singular. Before Augustine, people spoke of themselves to tell memorable stories, to give testimonies, examples to follow. Augustine, on the other hand, writes to speak of the particular path of a journey, the singularity of an experience that is confessed in order to reveal a perspective that must be dispelled so that reason can finally prevail. That's why he says:

"But to whom am I telling these facts? Not to you, my God. In your presence, I address the human race to which I belong, even if these pages reach only a minority. So why am I writing this? So that I, and all those who read these words, may think from what a deep abyss it is to cry out to you. What could be closer to your ears than a repentant heart and a life of faith?" (Goodwin, 1607).

This statement is very important. I write for myself and for the minority who feel that they are in the depths of an abyss. I write for those who are marked by wandering, so that the "I" that has appeared as a witness of an abyss can access a knowledge that no longer needs any perspective. Among other things, this wandering is organically linked to the fate that nature will have among us. If the "I" is the sign of a wandering, it is because the confession of oneself is equivalent to a reunion of the will with itself, a departure from evil and deviation. To better understand the figure of this deviation, let us recall a fundamental specification. Augustine says:

"If anyone says that the flesh is the cause of all vices and bad habits, precisely because the soul, in love with the flesh, lives in this way, there is no doubt that it is not fixed in the whole of human nature....Nor did the corruptible flesh make the soul sinful, but it was the sinful soul that made the flesh corruptible (...) Man did not become like the devil because he had flesh, which the devil lacks, but because he lived according to himself, that is, according to man" (Augustine, 2014).

In other words, the flesh is not the cause of evil; if it is corruptible, it is because the human will has corrupted it. God, as an omniscient Creator, could not have created an evil nature, an evil flesh. Hence the reminder that man did not become like the devil because he had flesh. The problem lies in what we might call the "politics of the will". The political relations within the will can be reversed. Man can want to live according to himself and not according to God. He can reverse the good that belongs to a free and rational will, breaking the political relations of hierarchy and obedience. This explains why the central sin for Augustine is disobedience. It was disobedience that originally made man sin by disregarding the obedience to God. The love of transitory things in the face of what is permanent and eternal, the desire for the inversion of values: this is true evil. Man was not created to live according to himself, but according to the One who created him, making his will his own. In other words, what the confession does is to restore a corrupted political order.

But let us take note of one point: to live according to oneself means for man, paradoxically, to have one's will outside oneself, because it means to act involuntarily, without reflection, supposedly like animals. The separation between human and animal comes about through reason, that is, through the ability to perceive and evaluate oneself, to be endowed with an inner sense that would allow us to judge and evaluate our own senses, not to be inert servants of an external causality. This would allow us, among other things, to distance ourselves from our passions and the instability that comes from being at the mercy of external contingencies. In other words, free will was created to allow the exercise of a second-order desire, a desire to have a certain desire or a desire not to have a certain desire.5 This reflexivity defines human exceptionalism and brings human's will closer to divine reason.

But this free will is not only characterised by what we will later understand as "reflexivity". It is also capable of understanding that nature should not legislate, should not be in charge, but should submit and allow itself to be governed. And this is where Augustine's fundamental theological operation comes into play, namely the definition of original sin as the axis of all Christian theology. Let us recall statements such as:

"Finally, and to put it in a nutshell, what was the penalty for the sin of disobedience if not disobedience? And what misery is more fitting for man than the disobedience of himself against himself, so that because he did not want what he could, he now wants what he cannot? It is true that in Paradise, before sin, he couldn't do everything, but he only wanted what he could do, and so he could do everything he wanted. But now, as we see in his descendants and as the Scriptures testify, man has become like vanity. Who can count what he wants and what he cannot, when his mind is contrary and his flesh, which is inferior to him, does not obey his will?" (Augustine, 2014).

This is a central passage. Original sin has a fundamental place because it explains the function of the internal civil war that human nature has become. Disobedience to God's will has become disobedience of self against self, disobedience of a flesh that no longer submits to the will, of a nature that is a hostile space. Since original sin, man has been the scene of a permanent split between the will and a principle of disobedience, which will have a specific name and will accompany Western anthropology like a shadow, namely libido. The libido, the worst form of misgovernment, because "the libido is so strong that it not only dominates the whole body, not only inside and outside, but also puts the whole man at risk" (Augustine, 2014).6

Augustine reminds us that before original sin there was no libido. Nakedness was not shameful because the libido did not activate the limbs against our will. But this immanence was broken, and shame is the affection that makes this break explicit. This is how corrupted nature is born, which must now be brought back to its place of submission to reason. Hence the importance of a statement like:

"There is no doubt that human nature is ashamed of this libido. And rightly so, for in his disobedience, which has left the sexual organs subject to their own movements and separated them from the will, the price that man has paid for his own disobedience is clearly shown. And it was fitting that its trace should appear especially in the members that serve the generation of nature, aggravated by the first great sin" (Augustine, 2014).

As we can see, the central problem is political, it is about who should rule and what should rule in man. Just as the libido must be controlled, the flesh must learn to obey. But for this to happen, human behaviour must not be subject to external causality, which can only happen when, at the limit, man is able to dominate nature, to impose a relationship of domination on it. The distinction between man and nature takes on its theological meaning. The recovery of this meaning shows us the real conditions for the construction of the unity of the self, of self-determination.

War Against Nature or Labour and Reflection

This political theological horizon will constitute one of the central axes of Western sensibility towards nature and our autonomy. To recover this history is to say that the emergence of nature is inseparable from the naturalisation of an instrument of self-government, from the defence of freedom understood as autonomous will. It is not possible to change our relationship to what we call "nature" while preserving such devices, such ways of understanding ourselves. Of course, resistance to such changes is not simply "grammatical", it is material. More precisely, it is the result of material processes that impose a social grammar that seems insurmountable to us.

In this sense, let us see how this political theological horizon unfolds with the development of capitalism, with its appropriation of nature by labour and its colonial expansionism. This is not to say that theological constructions provide systems of justification for economic models. Rather, it would be more accurate to say that they create subjective dispositions within which economic models can develop and assert themselves. As I said, the necessary articulations between capitalism and Christianity are an important topic in classical sociology. They should be deepened if we want to understand the matrices of the current crises, which have nature at their center.

For example, the idea of nature as something that must be subjected to the condition of property in a limitless expansionism, an idea that underpins capitalism and its colonial dynamic, can only develop itself in a social horizon that is already marked by the idea of nature as something that must be subjected to human being in a war that is necessary for the affirmation of our freedom. It needs this assumption to work. In other words, the idea of realizing the material conditions of freedom drives the idea of progress, economic development, growth, and prosperity. But it's important to remember that the idea of freedom, as it unfolds hegemonically within capitalist societies, is a theological operator. It couldn't be otherwise, given liberalism's dependence on theology.

By imposing itself as a model for economic development and the structuring of subjectivity, liberalism has succeeded in constantly accelerating economic progress. But for there to be progress, it must be imbued with the task of saving something from regression; for there to be development, there must be something understood as backwardness. And this is the place where nature will emerge. It will also be the place of all those who are "very close to nature", such as the Indian peoples. This brings us to the political theological controversies that would run through the century before the consolidation of liberalism, and which would inevitably influence it. These struggles took place in the largest world empire of the time, the Spanish empire of the 16th century.

The discussion of the conquest of America as a fair war, as well as the use of natural law to justify the right of conquest, is largely based on a theological anthropology that takes us back to what we find in Saint Augustine. Indigenous peoples are defined as backward, too close to nature, and should be ruled by supposedly superior peoples. The Aristotelian notion of natural servitude is used throughout. For Amerindian peoples would be characterised by barbarism, expressed in cannibalism, constant human sacrifice, and sodomy: signs of proximity to a nature that is not subject to reason. They must therefore be ruled by those who are already in a different stage, so that reason, which dwells within them, can find its strength.7 Conquest is therefore fair and necessary. But it is not only a fair war against inferior peoples. It is above all a fair war against the nature that expresses itself in them.

In this sense, this war prepares the material realisation of liberal individuality and its modes of economic action. There is a colonial trace of origin in the emergence of liberal individuality. And we should turn our attention to John Locke because it is in Locke that we find the relationship between the appropriation of nature by labour and the constitution of our freedom most clearly stated. Let us start, for example, with his statement:

"Though the earth and all inferior creatures are common to all men, yet every man has property in his own person. No one has a right to it except himself. It can be said that the work of his body and the work of his hands are rightfully his. Whatever he takes from the state that nature has provided and left there is mixed with his work, becomes something that belongs to him and therefore becomes his property (Locke, 1967, p.340).

This is a crucial text for understanding the hegemonic notion of freedom among us and its social consequences. Locke says that individual freedom is a question of self-ownership, of being the owner of one's own person. To think of the relationship to oneself, the notion of self-ownership, as property is something that will have countless consequences. But let us look at the second point in this passage. Property is a way in which the individual relates to himself and to the world. For property is above all an affect: the affect of the security of things that are completely under my dominion, of things that have lost their strangeness. And this can only happen when nature is subjected to labour.

The fundamental point, therefore, is how "work" from now on appears as the production of what is mine, of what is the mirrored confirmation of my own determination. It is not only a structure of recognition, but above all a structure of self-determination. Everything that man has removed from the state of nature has been mixed into the labour, and in this way something that is now his is found in the worked object. It is therefore his property. It is his mirror. And through this reduction of nature to a mirror, labour can appear as the central actor in the realization of individual autonomy.

This fact can be better understood if we recall how this notion of labour is the material realization of a certain notion of reflection, which, we should always remember, was born with Locke.8 It is reflection that will allow the emergence of the individual, which will henceforth be the term preferentially applied to those endowed with a personal identity. And personal identity will be defined as follows:

"What the concept of person represents, and what I believe is thought itself, is the same thing thought in different times and places; what is consciousness only because of this, which I believe is essential to thought and inseparable from it and essential to it. It is impossible for someone to perceive without being aware that he is perceiving" (Locke, 2007, p. 302).

In other words, personal identity is directly linked to the ability to be the same thinking thing in different times and places, which means to understand oneself as the same conscious agent in the dispersion of time and space. A person's identity is understood not as the identity of a substance, but as the identity of an actvitiy called consciousness. Consciousness thus appears as the unifying principle of existence in time and space. Therefore: "as far as consciousness can be extended backwards to any past action or thought, so far does it reach the identity of a person" (Locke, 2007, p. 302). This operation by Locke is crucial: all personal identity is an expression of the presence of consciousness as a principle of unity. For "consciousness" is above all the name we give to that activity which makes me see myself seeing myself in every present and past action or thought. If Locke has to remind himself that it is impossible for someone to perceive without perceiving that he is perceiving, it is because reflection must be an operation immanent in the whole of my existence. All the facts of consciousness are by right accessible to reflection; they can be transformed into a representation for reflection.

Something like a "first-person identity" thus emerges. Unlike a substance, whose identity is usually described in the third person and whose identity does not change if it is not described in the first person, an identity of consciousness only exists at the moment when it can be assumed in the form of a first-person activity. I am not identical to what I do not recognise myself in, even if it is actions that my body has done or that I have done involuntarily.

In other words, for Locke at least, reflection is an activity by which the will ensures its mastery over things, memories, impressions, and perceptions, by subjecting them to a particular regime of presence, which we understand as "representation". It is an appropriation, just as work is an appropriation. As I said earlier, work takes things out of the hands of nature. It does so by materially realising the principle of identification inherent in reflection. And it is impossible not to notice the profoundly theological dimension of this horizon:

"God gave the world to men in common, but since he gave it to them for their own benefit and for the greater pleasures of life that they could enjoy from the world, it is not possible to suppose that God thought that the world should always remain common and uncultivated" (Locke, 2007, p.191).

One wonders why God does not like things to remain common and uncultivated. Why does he need human beings to carry out a project of shaping and appropriating nature? It would then be necessary to ask what is meant by "work" in this context, what are its specific historical-material coordinates.

Locke believes that there are spaces in which nature has not yet been subjected to work, multiple spaces in which we would find the myth of virgin nature, of empty and unworked space, of land close to nothing, ready to be taken over and colonized. Vacuum domicilium.9 It is clear that, among other things, this "makes it possible to distinguish between 'working and rational' men and the others, the natives: in this way, the original societies are excluded from legitimate legal relations with the land, since they are nothing but hunter-gatherers, or at least are seen as such" Charbonnier (2021, p.65). This anthropological illusion, so deeply rooted in us, of the distinction between phases of anthropological development (hunter-gatherers and agricultural peoples), an illusion shared by Locke, now appears to be something closer to an ideological construction linked to the value of labour. Let us recall David Graeber's and David Wengrow's defence that the distinction between hunter-gatherers and farmers should be seen as possibilities that cross the same society according to the season, and that the figure of the hunter-gatherer who simply enjoys what nature provides is a myth. Theirs is a fundamental statement such as:

"European-style farming is just one of thousands of ways to cultivate land and increase its productivity. Where the settlers saw only wild expanses that seemed never to have been touched by human hands, there were in fact landscapes that had been actively tended by the indigenous population for hundreds of generations, using various methods: controlled burning, weeding, pruning, fertilising, organising estuary structures at different levels to extend the habitat of a particular wild flora, creating shellfish gardens in intertidal zones to improve the reproduction of crustaceans, building dams to catch salmon, sturgeon.... Not only did these tasks require a great deal of work, but they were also regulated by indigenous laws that established rights of access to forests, ponds, root beds, prairies, or fishing grounds, as well as the right to harvest such and such a species at such and such a time of year, etc." (Graeber & Wengrow, 2021, p.194).

This is a very concrete way of understanding how the technodiversity of multiple social forms must be radically denied in order for the notion of pristine nature to be constituted (Hui, 2020). This same technodiversity develops, in many cases, without the need to make distinctions between domestic space and wild space, between the space of nature and the action of culture, where the space of production is discrete, in continuity with the general space, because it ignores the extractive logic linked to primitive accumulation. In other words, if Locke is a victim of this illusion of non-working lands, it is because his concept of labour is organically and exclusively linked to the capitalist production of value. A production that has to break what the young Marx called the "metabolism between human being and nature" in order to reduce what is natural to the condition of a reserve, a stock, a condition for the valorisation of value and a justification for colonial expansion (see Marx, 1992).

It has been said that capitalism is a religion. Indeed, it should be remembered that its dynamic of accumulation and expansionism would be impossible without the secularisation of the concept of nature as what is available for the realization of human exceptionality, like Adam, who received from God the enjoyment of all the fruits of the earth. But this exceptionality requires a transformation of nature, its transformation into property. The extensive right to private ownership of land requires that land use be subordinated to the imperatives of production, that owners have the right to divert water to mills, that spaces be fenced off and animals tagged, that those who live on common land without an owner be expelled. It is not for this reason that Locke's text, Chapter V of the Second Treatise of Government, which serves as the basis for our discussion, very clearly establishes land ownership as the central axis of property relations: "But the principal question of property is now, not the fruits of the earth, and the beasts that live upon it, but the earth itself" (Locke, 2007, p.190). For it was a question, among other things, of justifying a new form of economic organisation imposed by colonial expansionism, a new technology of production born of the destruction of the commons by what the English call "enclosure", which determined the process of what we now understand as primitive accumulation. It was mainly a matter of transforming land into capital that increased in value. This inaugurated the two main illusions of capitalism, namely the infinite extraction of value from land and labour.

A New Concrete Horizon of Social Struggles

If the concept of nature is the expression of a junction between economic rationality and theology-politics, the possibility of its destruction depends on social struggles capable of liberating nature from the condition of being the object of labour, of changing the boundaries we establish between nature and society, and of structurally reconfiguring what we should understand by autonomy.

Finally, it would be appropriate to point out that critical theory must be able to find models for generalising social action on the basis of concrete struggles unfolding in our present. It seeks the potential opened up by social struggles. In this sense, we must be attentive to the reconstructions in the field of our social grammar that certain struggles presuppose.

For example, anyone who reads the current constitution of Ecuador will find the following text in article 71: "Nature, or Pacha Mama, in which life is reproduced and realised, has the right to full respect for its existence, as well as the right to the maintenance and regeneration of its vital cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes" (CRE, 2008). This was the first time that a constitution recognised nature as a subject of law. Similar legislation appeared in New Zealand, but for localised areas (Whanganui River, Te Urewera Forest, Mount Tarakani). In Bangladesh, Colombia and India, court decisions have been based on the rights of nature. Bolivia has passed a series of laws on the rights of Mother Earth, as has Uganda.

In the case of Ecuador, the constitutional article was the result of a constant and unrelenting series of popular indigenous struggles that have marked the country's recent history. But it is worth remembering that this constitutional provision points to something much greater than the consolidation of a legal innovation aimed at providing more instruments of action for those seeking ways to regulate capitalist extractivism. It is, in its own way, the expression of a political awareness that the modern concept of nature is the result of dichotomies rooted in an active metaphysics that needs to be destroyed. The brutality of extractivism, with its combination of progress and destruction, would be impossible without the social acceptance of these dichotomies with their legal-normative existence.

Integrating nature into the horizon of what we recognise as the "subject" had nothing to do with "animistic" archaism or messianic mysticism. Rather, it was a shrewd political strategy. It was based on the awareness that a fundamental change could occur from the moment that nature was no longer socially experienced as a system of things to be used, no longer understood as an object, but as a subject. For legal innovation tended to produce a collapse in the way we define what can be used and what cannot be used, what is endowed with agency and what is not, what is a thing and what is a person, what can be property and what cannot be property.

Must legally recognized agency necessarily take the form of will? And what about vital cycles that produce agency because they unfold processes, structures and functions that are open to chance and contingency, even if not exactly in the form of will? Should not we give them the dignity of subjects? These questions show us how the generalization of the category of the subject to non-human entities leads to a better understanding of how we are affected by that which does not necessarily bear our image, how we are caused by that which removes us from our supposed autonomy. In this way, a different concept of freedom can be generated. It makes possible the emergence of a different figure of the political subject. And perhaps this change can explain why Ecuador will be the scene of an unprecedented decision. In 2023, in a plebiscite, 58.3% of the electorate decided to prevent oil exploration in Block 43 of the Yasuni Park. In other words, the economic order could be challenged in a place where what we call nature is no longer just an object to be exploited.

- On the relationship between modern physics and Christian religion, see for example Kojève & Copin (2021).↩

- As we can see in Latour (2006).↩

- As we see in Weber (2004).↩

- The consequences of such a conception have been well developed by Derrida (2003). On the theological nature of the notion of will, see also Agamben (2008).↩

- On the notion of second-order desire, see Frankfurt (1971).↩

- Foucault (2021, p.334) understood this point well when he said: "Fallen man has not fallen under a law or a force that subjugates him entirely: a schism marks his own will, which divides, turns against itself and escapes what it can will. This is the principle, fundamental in Augustine, of reciprocal inobedience, of disobedience in return. The revolt in man reproduces the revolt against God".↩

- See, among others Sepulveda (2016).↩

- On this subject, see Rorty (2009).↩

- On this subject, see Arneil (1996).↩