1. Introduction

A paradigm shift is underway in the behavioral sciences.

For decades, the symbolic computational model of the mind dominated cognitive science. It had a theoretical foundation called the Physical Symbol System Hypothesis. This view had a behavioral aspect known as information processing psychology and a computational aspect called symbolic artificial intelligence.

A model of mind based on what has been known variously as parallel distributed processing, connectionism, or neural networks was originally conceived around the same time as the symbolic computational model of mind, but was considered by many to be unworkable (Minsky & Papert, 1988). For decades, connectionism developed in parallel with symbolic AI. Over the years, connectionist approaches went by a variety of names: parallel distributed processing (PDP) (Rumelhart & McClelland, 1986), neural networks, and now Deep Learning and Generative AI.

The latest version of the connectionist approach has a behavioral aspect now known as predictive processing (PP), and a computational aspect known as Generative Artificial Intelligence (genAI). In recent years, genAI has outperformed symbolic AI on a wide range of tasks that are taken to be signs of human intelligence. Some researchers believe that the behavioral aspect, predictive processing, promises to unite neuroscience, which has always occupied the core of cognitive science, with a number of approaches that have previously resided on the periphery of the field (Clark, 2016). The computational aspect, genAI, promises or threatens to profoundly change our world for good or ill, or both good and ill.

Generative AI has recently become the future of technology. Will Predictive Processing become the future of behavioral sciences? How might these developments change the way we imagine human cognition?

There is a potential conceptual trap in these developments. Much of cognitive science has subscribed to the view that "the mind is in the brain", or "the mind is what the brain does". These ideas are pervasive in today's discussions about genAI and its relationship to human intelligence. In the public imagination, genAI is a model of the brain, and the individual brain is the seat of human cognition and cognitive accomplishment. We are warned that some genAI systems will soon be more intelligent than any person, and that this presents a perhaps existential threat to human civilization. GenAI may well present an existential threat to humanity, but it is not because of its relationship to individual cognitive function. As is well known, and as I will show again in the pages below, what makes humans smart is not simply the properties of individual brains. Because neural nets are inspired by the organization of neurons in a brain, the temptation is strong to repeat the mistakes of the past and reduce intelligence to the function of a brain. However, this moment in time presents us with an opportunity to avoid the trap of the conceptual collapse of mind to brain. Perhaps it seems paradoxical that a better model of brain function can help us avoid attributing too much to the brain. I hope that by the end of this paper, you will agree that this is the case.

1.1. My Goal

I intend this paper as an attempt to seize this opportunity; to show how the predictive processing approach implies that the mind transcends the boundaries of the individual brain. I will describe a new framework that incorporates predictive processing to inform and transform our ways of looking at real-world activity. Because I'm a cognitive ethnographer trying to detect, highlight, illuminate, and perhaps explain the cognitive aspects of everyday human behavior, I need a slightly different framework from the usual predictive processing model of brain function. In addition to the generative aspects of PP, my observations of real-world activity make clear that people's engagement with the world is multimodal and continuous. I combine these features to create what I call the Multimodal, Generative, Continuous (MGC) approach. I propose to explore human activity seen through the lens of this generative model of perception, action, and thought. This MGC model is made possible in part by the rise of PP as a demonstration of a plausible model of the generative aspect of individual cognitive processing, but it goes beyond other approaches by insisting on multimodality and the continuity of coupling between an organism and its environment.

1.2. The Role of Theory and Researcher Imagination

When we as researchers confront phenomena, we always do so using a network of assumptions. If we are paying attention, we may ask ourselves, "What do our assumptions permit us to imagine?" If our theoretical assumptions indicate that a phenomenon seems unlikely or not supported by theory, then we are unlikely to pursue it. If I believe I am seeing phenomenon x in real-world activity, but x is implausible in the theoretical framework that I assume to describe human cognitive function, a tension is created. I might ask myself, "Am I wrong about the phenomenon, or do my assumptions not serve my needs?" For decades, I have been struggling to find plausible theoretical descriptions for several phenomena that appear in my observations in the field. My excitement and enthusiasm for the MGC framework stems from the fact that many observable phenomena that formerly seemed implausible follow naturally from the MGC framework.

The MGC framework permits us to imagine cognition working in ways that fit fine-scale observations of ongoing human (and non-human) activity. I know that I am not alone in struggling to find a fit between observation of everyday life and cognitive theory. Other approaches that have developed in the past two decades to address what happens at the interface of organism and environment experience similar tensions.

These tensions are among the forces driving the paradigm shift in the behavioral sciences that I pointed to in my opening sentence. Predictive processing (and I think even more so, the MGC approach) promises to unite many fields that have, until now, remained on the periphery of mainstream cognitive science. Consider ecological psychology (Gibson, 1986; Kugler & Turvey, 1987), dynamical systems theory (Kelso, 1995; Port & van Gelder, 1995; Spivey, 2007; Thelen & Smith, 1994), embodied cognition (Gibbs, 2006; Johnson, 1987; Lakoff & Nuñez, 2000), embodied robotics (Beer, 2008), enaction (Maturana & Varela, 1987; Stewart et al., 2010; Thompson, 2007), predictive processing (Friston, 2008), extended cognition (Clark & Chalmers, 1998), ecology of mind (Bateson, 1972), distributed cognition (Hutchins, 1995a), situated action (Suchman, 1987), cultural-historical activity theory (Cole, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1985), actor network theory (Latour, 2005), and le coursd'action (Theureau, 2015). All these approaches attempt to put the focus of study on the interactions of agents with their social and material environments. These approaches consider sensory and motor processes to be part of the apparatus of thought rather than peripheral devices that deliver the world to a central processor in the form of symbolic representations. None of these approaches is well accounted for by the traditional computational model of mind. They have chaffed under the weight of an old model that makes it difficult to imagine the phenomena they study. This includes phenomena that exist in a system that comprises brain, body, and world, and that cannot be understood without considering all the components in interaction.

In this paper, I want to sketch a new edifice of assumptions to guide our thinking about cognition in human activity. I will illustrate the utility of these assumptions by using them to analyze vignettes from everyday life. The analyses presented here are exploratory in the sense that I'm trying to see what is highlighted in human activity when we assume that people are, among other things, MGC systems. This has not been done before. We do not know in advance that such analyses will yield valuable results.

1.3. Researcher Attention

Theoretical frameworks always shape what we see. PP systems learn the flow of experience in the sensory and motor systems, so that's where our attention is directed. Generative AI models develop internal processes that can produce, predict, and imagine the course of their experience, but when there are 10^12^ parameters in a computational network model, speculation about the details of internal processes is intractable and, for our purposes, unnecessary. At present, we can describe the general principles of how the PP system (and supposedly the brain) does its work, but the details of how any particular task is accomplished remain beyond our reach. The opaqueness of the depths of deep learning systems channels our attention toward the interaction of an organism with its environment. In earlier approaches, attention was focused on internal processes, and the stuff outside the brain was left blurry - literally out of focus. I now propose to invert that situation. The observable actions in, and interactions with, the cultural world are brought into sharp focus, and internal processes may be present in peripheral vision but remain out of focus. PP is useful for me partly because of this effect. Incorporating PP in my theoretical base directs attention from unknowable internal processes to the observable behavior of people in real world activity.

1.4. Constraints on the Stories We Tell

It can be liberating to feel no obligation to imagine in detail the internal machinery of thought. But if that is no longer our story, what stories shall we tell? And where does one find the constraints to which these stories must be responsible? I will try to show how constraints on models of cognitive function can be derived from observations of behavior contextualized by deep cognitive ethnography.

In some cases, examinations of ongoing activity in terms of MGC will lead to speculations that cannot be fully evaluated on the basis of observations in the field. In those cases, I hope to raise questions that can be investigated by other cognitive scientists using other methods.

2. Background: Inventing Cognitive Ethnography

Let me provide some autobiographical background to my project.

I am a cognitive scientist, but I was originally trained as an anthropologist. In an analogy of cognitive science with biology, I would position myself as a naturalist. That is, while most of my colleaguesstudy cognition in laboratory settings, I have always studied cognition as it occurs in the wilds of everyday life.

Every proper study requires a theory, a method, and an object of scrutiny. As a naturalist of human activity, I put these pieces together as follows: The theory directs our attention. It says what to look for and how to look. The method captures events in the object of scrutiny and identifies them as instances of concepts in the theory.

2.1. Reasoning in Trobriand Island Discourse

When I started out in the 1970s, it was widely believed that primitive technology implies primitive thought. The fact that illiterate third-world adults performed on IQ tests about like 10-year-old children in Europe or North America was a robust finding in cross-cultural psychology (Dasen, 1972). In the summer of 1973, I was one of three graduate student researchers under the direction of UCSD anthropology professor Theodore Schwartz, who went to Manus Island in Papua New Guinea to conduct such a study. We administered a battery of intelligence tests to adult non-literate farmers and fishermen in several villages. We replicated the expected finding. Many people concluded from studies like these that non-literate unschooled adults in the third world think like children. But something seemed wrong to me. In everyday interaction, these people did not seem in any way mentally impaired. Furthermore, when the children from these same villages went away to school, they scored about like their age contemporaries in the Western world. There was clearly nothing wrong with the brains of the people. What was going on?

With an intelligence test of the sort our team used in Manus, the theory concerns mental abilities. The object of scrutiny is the mental abilities of the subject(s) and the test is a method to capture aspects of those abilities and assign them as instances of the concepts in the theory, i.e., inference, problem solving, abstract thinking, etc. When researchers take an intelligence test into the field, they put the burden on the subjects to figure out the nature of the tasks presented by the test. One can never be sure how much of the observed performance on the test is due to the abilities of the subjects and how much is due to their attempts to understand the nature of the tasks. Since every culture sets for its members many cognitive tasks, I thought perhaps we should, instead, observe real world cognitive activities, and put the burden on the researcher to figure out the nature of the task. We could still make inferences about cognitive capabilities by analyzing performance in the task. That is, with a sufficiently thorough understanding of the task, observed behaviors may be identified as instances of concepts in a theory of cognition.

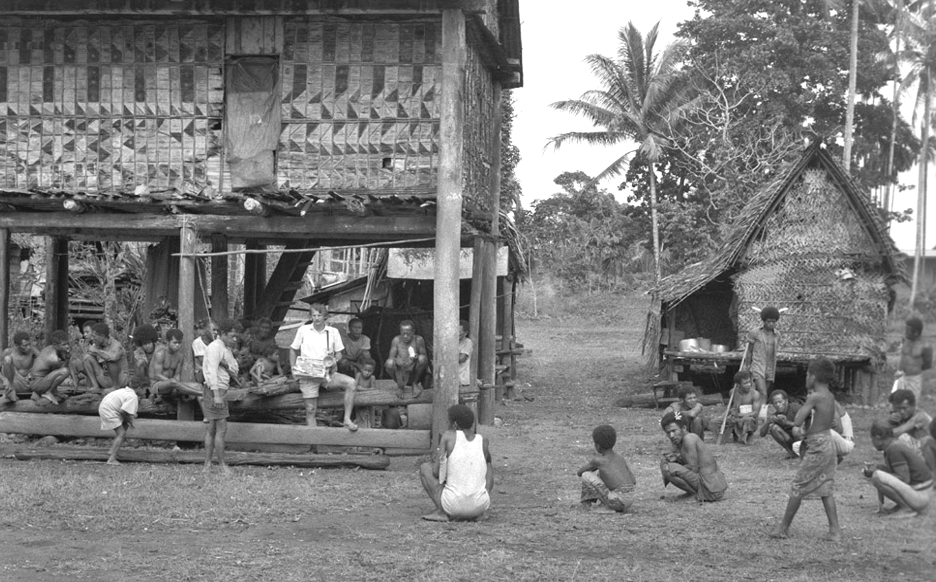

Funded by the Social Science Research Council, I went back to Papua New Guinea in 1975. Following in the footsteps of the great ethnographer, Bronislaw Malinowski, I went to the Trobriand Islands to do my PhD dissertation research. The Trobriand Islands was an apt choice because some authors, working from Malinowski's transcriptions of magic spells, had concluded that the Trobriand Islanders did not think logically (Lee, 1949). Once installed in a village, I searched for a naturally occurring activity that would allow me to assess reasoning abilities. I settled on land litigation. Because land litigation is conducted in public, I could record performances in the task. Land litigation is clearly cognitive because litigants must construct a narrative history of a piece of land that results with them holding rights, while simultaneously heading off anticipated counter arguments of their opponents. And because, on a small coral island, nothing is more important that rights in land, the motivation to take the task seriously is built into the activity.

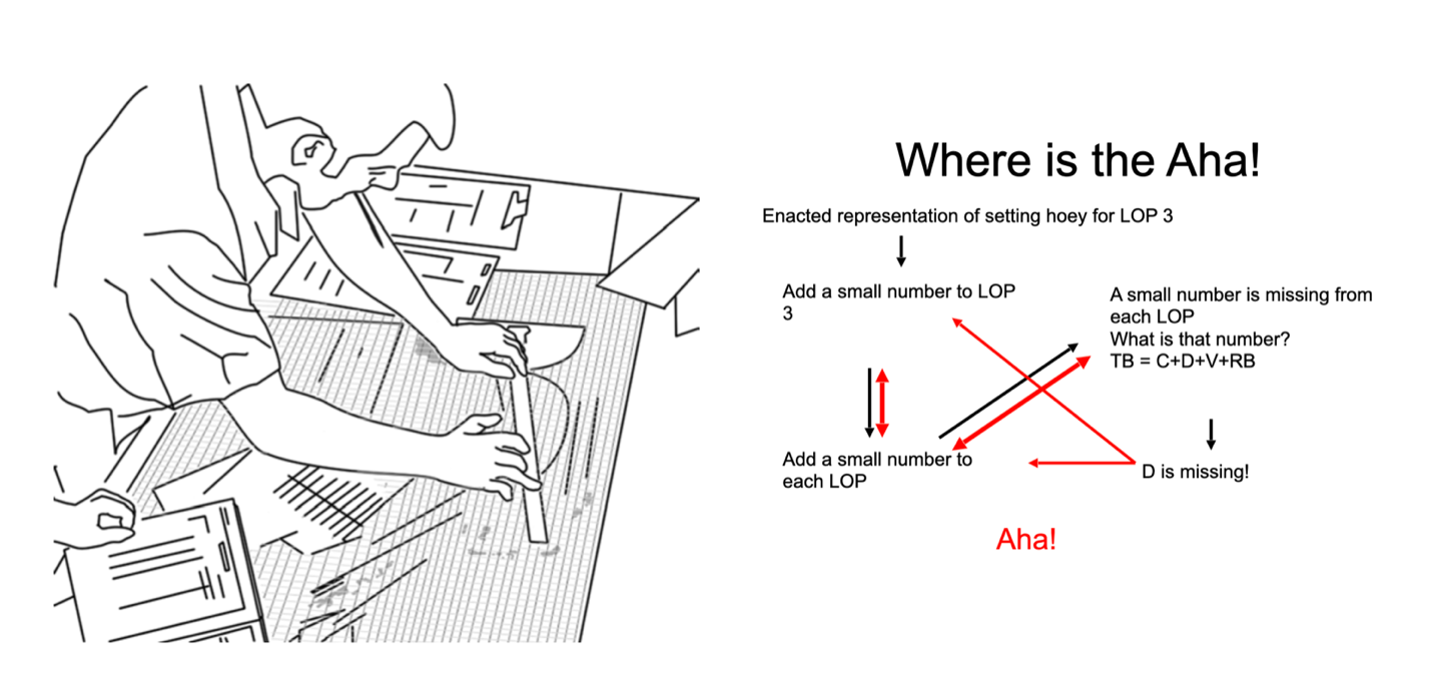

Figure 2.1. The author recording land litigation in a Trobriand Island village in 1976

Photo by Dona Hutchins

My theory was a combination of propositional logic and schema theory, as it was then developed in cognitive science (Rumelhart, 1975). Schema theory posits underlying conceptual structures that bring organization to knowledge and belief. A schema for buying, for example, includes roles for a buyer, a seller, an item to be bought, and a price paid. The schema describes relations among these roles. The buyer pays the price to seller in exchange for the item. The schema also specifies logical relations. The payment of a price is a necessary condition for the transfer of an item. This can be expressed as a premise: The transfer of the item implies that a price was paid. Binding actual events and things in the world to the roles in the schema produces propositions that may be assigned a truth value. "John paid Jane $2" is a proposition, which might be true or false. If the proposition "John paid something to Jane" can be shown to be false, it can be inferred that no item was bought by John from Jane. T implies P. P is observed to be false. Therefore, T is false. This is an example of modus tollens inference.

Adapting to the needs of the situation on the ground, I developed a first draft of an approach that I would later call Cognitive Ethnography. This is regular ethnography, as practiced by all sorts of anthropologists, plus some kind of recording of naturally occurring activities, followed by micro-analysis of the fine-scale details of the recorded activity.

Cognitive Ethnography begins with the classical method of anthropological fieldwork and participant observation. To do this sort of ethnography, it is essential to gain competence in the language that people speak in their everyday lives. Trobriand Islanders speak an Austronesian language known in the literature as Kilivila or Boyowan. My wife and I created a dictionary and a grammatical sketch of the language. Our dictionary is available online. Prior to our work, the only available materials were short word lists assembled by missionaries. Since then, a comprehensive grammar and dictionary has been published by Gunter Senft (Senft, 1986). In addition to writing field notes and taking still photographs, I made audio recordings of land litigation as it occurred in the village where I lived. Through extensive interviewing and a failed attempt to make my own garden, I documented gardening practices and the principles of land litigation.

I transcribed audio recordings in the Trobriand Island vernacular. I then performed a careful micro-analysis of the discourse, identifying statements in the data as instances of the concepts in the propositions that constitute schemas for transfer of rights in land. This permitted me to determine the logical relationships among the utterances produced by the litigants in their public discourse, and to identify the inferences using the typology of propositional logic. From this analysis, I was able to conclude that the Trobriand Islanders make the same kinds of inferences that we make. They are just as logical (or not) as your average American or European. This work was published in my book, Culture and Inference (Hutchins, 1980).

Propositional logic and schema theory produce re-descriptions of observable behavior. They permit us to identify inferences in the discourse as instances of strong inference (modus ponens and modus tollens) and plausible inference (affirmation of the consequent and denial of the antecedent), but they provide only weak constraints on the nature of the internal states and processes of the litigants. The observed behavior might have been produced by some internal symbol processing apparatus, or by some other unknown process. Using the language of the time in cognitive science, one would say that the observed data were rule-described, but not necessarily rule-generated. And that is fine. It is not always necessary for the theory to be a true description of internal processes, nor for the data to tightly constrain internal processes, to make useful assertions about cognitive processes. Inferences made in discourse are available to direct observation and can be placed in the typology of propositional logic as long as one knows the schemas in use and knows the particulars of the subject of the discourse sufficiently well to instantiate the schemas as propositions with truth values. Of course, documenting the schemas and knowing the particulars of each case requires extensive ethnographic investigation.

While I did not know what sorts of internal processes produced the observed behavior, I did suspect that the processes, whatever they were, must be quite general. At the time, I called the processes the cultural code. After a discussion of the many kinds of work the code seemed to do, I said,

"Terms such as problem solving, planning, understanding, decision making, and explanation are often taken as descriptions of cognitive processes. In light of the uses of the cultural code observed in the previous chapter, I take them not to be descriptors of various distinct processes so much as descriptors of the conditions under which, or the task environments in response to which, the cultural code (as a process) is applied." (Hutchins, 1980, p. 110)

This speculation, made in the late 1970s, appears prescient in the light of claims made in the past decade concerning the operation of the brains conceived as predictive processing systems.

This project on Trobriand Island land litigation gave rise to the recipe for all my subsequent cognitive ethnographic research: Begin with traditional ethnography. Choose a small naturally occurring activity. Record data on the performance of the activity. Analyze the data using whatever theory seems best to reveal the cognitive aspects.

Recording technology imposes strong limitations on what is possible with such a method. Malinowski could not have done this project because it requires the analysis of the words people actually say, and in 1916 he had no way to record ongoing speech. Taking notes on what people say in ordinary conversation is not enough. In fact, the only sort of discourse that Malinowski could reliably capture verbatim was magic. Magical spells can be recorded accurately in written notes because the effectiveness of a magical spell depends on the fidelity of its repetition. A spell must be recited exactly in order to achieve the desired results. A magician informant can be asked to repeat a spell as needed to get it down in writing. Malinowski did transcribe, translate, and publish many magical spells that were recited for him by Trobriand magicians (Malinowski, 1965). Unfortunately, magic has a very different logical structure from everyday discourse. Normal cause-and-effect relations are distorted in magic by the fact that magic is, well, magical. This means that attempting to assess Trobriand Islanders' reasoning abilities by analyzing the language of magic will not produce accurate results.

Of course, there is so much more to the performance of public litigation than the logical structure of the discourse. The audio recording also captures prosody, and other properties of the verbal stream, as well as other sounds such as the wind blowing, rain falling, dogs barking and roosters crowing in the village. Audio, however, cannot capture facial expression, gesture, body posture, the sun beating down or covered by cloud, the coming and going of participants, and smoke drifting through the village.

This illustrates how a theoretical framework, together with data collection apparatus, forms a filter and a spotlight that selectively highlight certain aspects of the phenomena while disregarding or completely failing to see others.

2.2. Ship Navigation

In the early 1980s, I had a position with the US Navy as a personnel research psychologist (the Navy didn't seem to know how to hire an anthropologist).

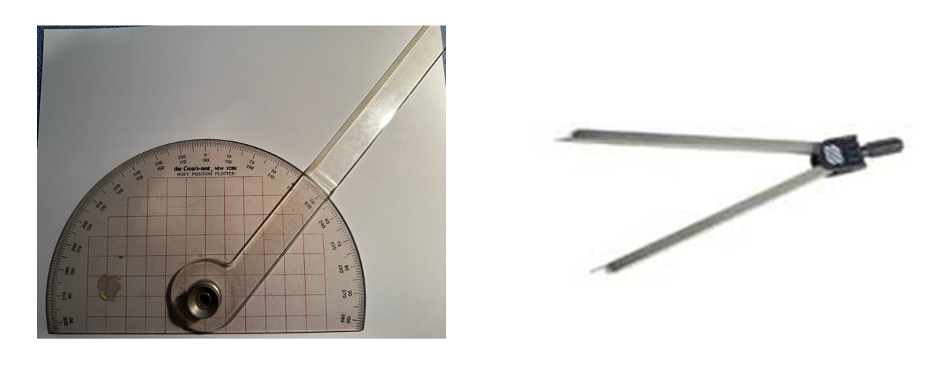

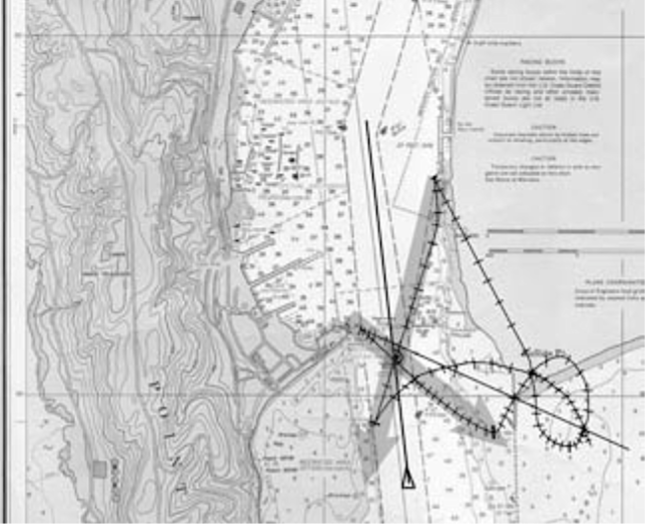

At first, I rode ships in the engineering spaces doing ethnography on the operation of steam propulsion systems in support of the development of the STEAMER computer-based instructional system (Hollan, Hutchins, & Weitzman, 1984). On subsequent field trips I moved to the Combat Information Center where I worked on radar navigation systems. There I was able to discover and document how an innocent looking deviation from procedures caused major problems for task-force coordination. In those days, operations specialists in the CIC used a polar-coordinate plotting sheet called the maneuvering board to compute important features of the ship's relationship to other ships, such as closest point of approach, collision threat, scouting tracks, and so on. Naval training centers experienced a high rate of failure in courses teaching the use of the maneuvering board. I designed a computer-based training system for use of the maneuvering board that reduced the failure rate to about one tenth of its previous value. This system was subsequently adopted as standard training aboard every ship in the US Navy (Hutchins & McCandless, 1982).

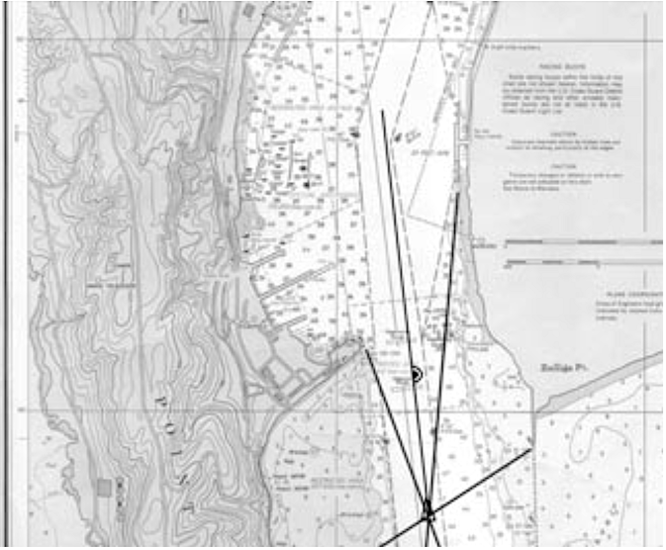

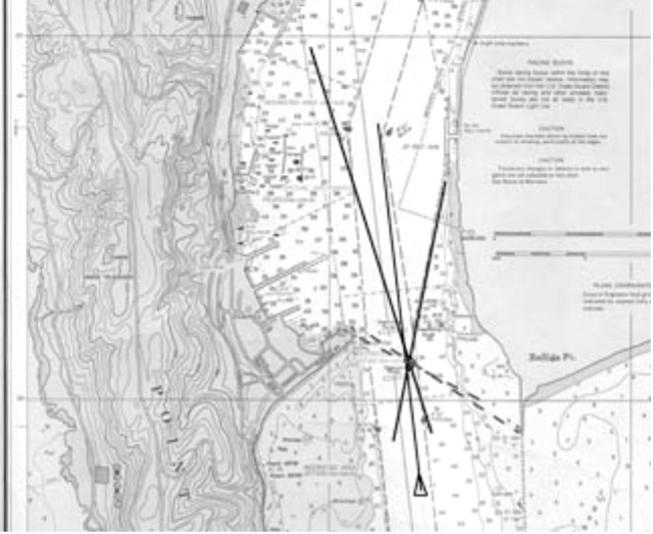

Neither the engineering spaces nor the Combat Information Center have windows through which one can see the world outside the ship. In all my observations to this point, I had not yet experienced either of the two most romantic moments aboard ship, the departure from and the arrival at a harbor. Finally, at the conclusion of a trip from San Diego up the west coast aboard the amphibious transport dock ship, USS Denver, I decided to go onto the bridge for the entry into the Straits of Juan de Fuca and the arrival in the port of Seattle. The bridge was busy, and the activity of the navigation team was simultaneously familiar and new to me. Having been trained as a navigator of offshore racing yachts and being a member of the last generation of celestial navigators, I knew a fair bit about navigation, but nothing at all about how it was done on ships. After observing the navigation activity on the bridge of the USS Denver, I resolved to make a more focused study of bridge navigation.

My theoretical framework was the symbolic computational model of mind. This theory postulated a central cognitive processor that did the thinking by manipulating strings of symbols. Sensory systems transformed sense data into symbols to be passed to the central processor. The central processor could pass symbols to motor systems that transformed strings of symbols into movement. Newell and Simon called such a system the "Physical Symbol System," and proposed in the Physical Symbol System Hypothesis (PSSH) that wherever intelligence is found, it will be found to be a PSS (Newell & Simon, 1972).

Thus, armed with the dominant theoretical frameworks in cognitive science at the time and a good start on the ethnography of Western navigation, I set out to learn about the cognition of individual navigators on Navy ships. I began making field observations on the bridge of several ships.

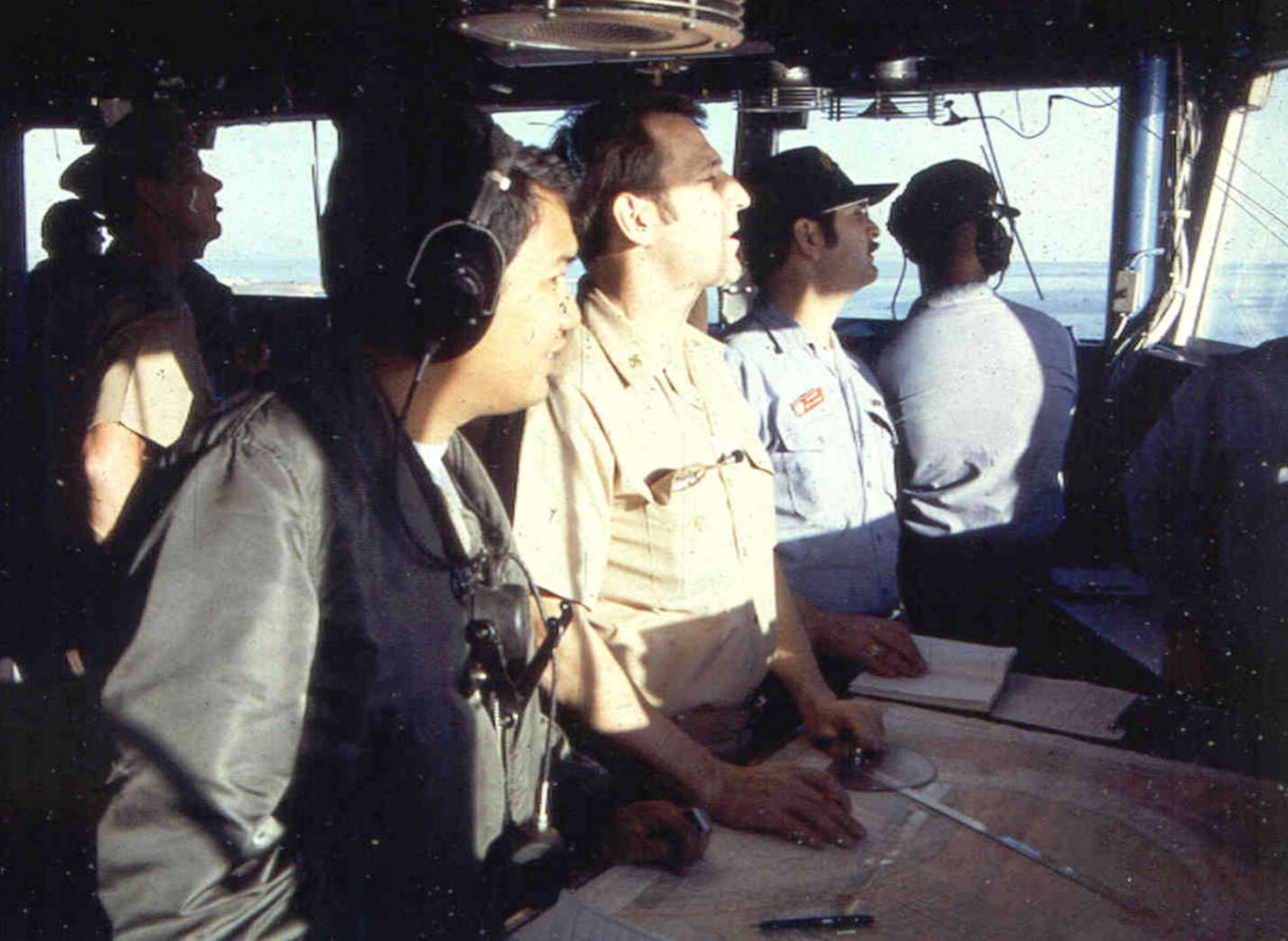

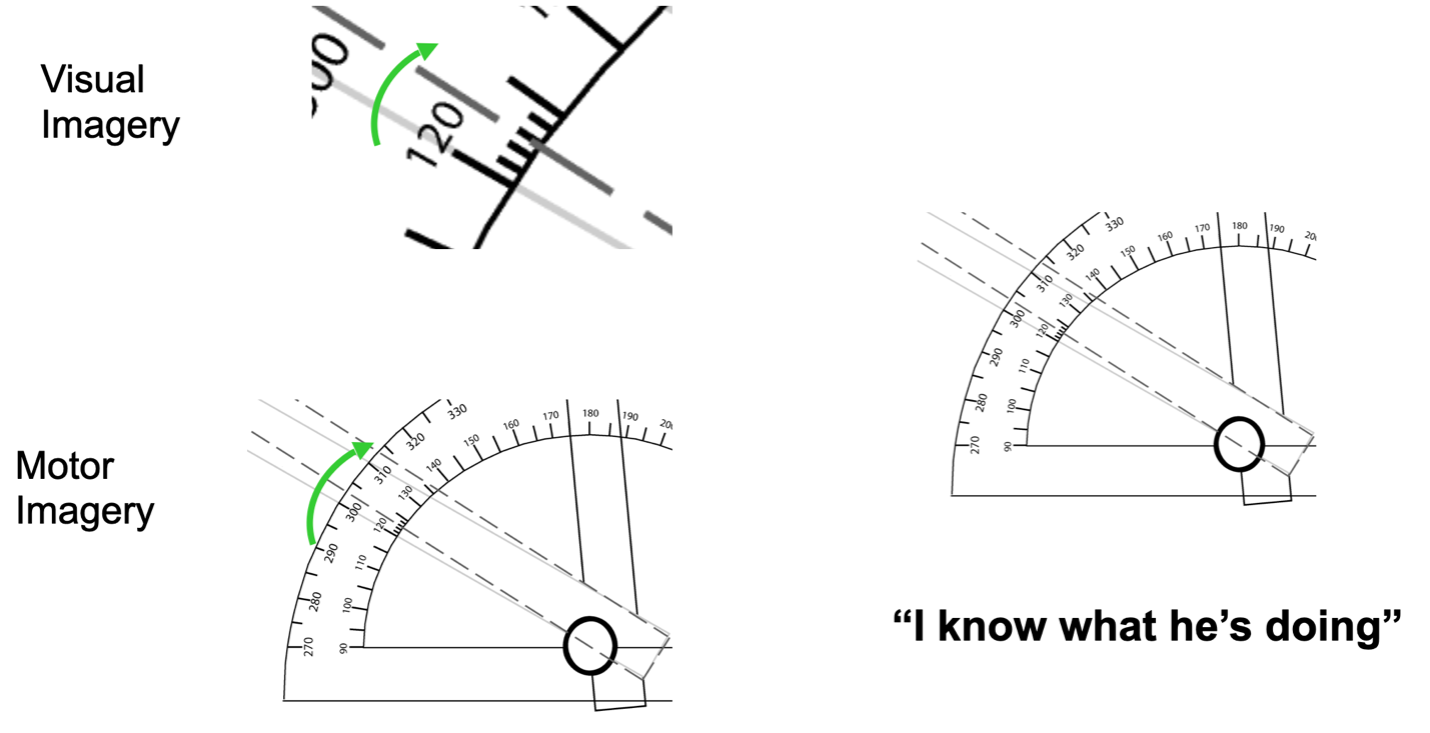

Figure 2.2. The navigation team at the chart table on the bridge of the USS Pala

Photo by the author

I experienced an epiphany one afternoon while standing on the bridge of a ship watching the navigation team work as the ship entered San Diego harbor. It suddenly became clear to me that the outcomes that matter to the ship, such as whether it went aground or not, were determined by the team rather than by any individual navigator. Writing up my field notes later that night, I speculated that the navigation system, comprised of four quartermasters plus their tools, might have cognitive properties of its own.

It came as a surprise to discover that the PSSH provided an excellent metaphorical account of what was happening among the members of the team. They were creating both symbolic and non-symbolic representations of the situation of the ship and propagating and transforming those representations. There was a flow of information through the system. There were long-term memory stores in the form of charts and short-term memory stores in the form of logbooks and pencil marks on the charts. There were analog-to-digital transformations implemented in the telescopes used for observing bearings of landmarks and digital-to-analog transformations implemented in the plotting tools.

By the time I wrote Cognition in the Wild, eight years after my epiphany on the bridge, I understood that the fact that the activities on the navigation team fit perfectly with the Physical Symbol System Hypothesis was no accident. Contrary to the belief in cognitive science at the time that the computer was made in the image of the human (Simon & Kaplan, 1989), it was clear that the computer, which implemented a PSS, was made in the image of a socio-technical system like the navigation team. I made this argument in the last chapter of Cognition in the Wild (Hutchins, 1995a).

The sort of symbolic cognition implemented by the navigation team and its tools captures something important about humans. It is the secret of our success as a species. We represent the world in external symbolic expressions such as equations. We transform the symbols using rules that respond only to the form of the symbols, not to their meaning. And then we re-interpret the new symbolic expressions as descriptors of states of the world. This process of symbolic representation and manipulation is the foundation of logic and mathematics, science, and engineering. It allows us to predict the future and describe that which cannot be directly observed. It gives us access to and control over the absent and the abstract.

Looking back over 40 years, I now see that armed with the core concepts of classical symbol-processing AI and information processing psychology, I went looking for physical symbol systems on the bridge of a ship. And I found them. I honestly expected to find them inside the navigators, but they were not where they were expected! They were not, as far as I could tell, inside the navigators. They were, instead, between the navigators, or among the navigators and the culturally elaborated task setting in which the navigators worked. What makes us smart? It's more than big brains. Humans create their cognitive powers by creating the physical and social environments in which they exercise those powers.

This epiphany was the origin of the approach I came to call "distributed cognition." Here was an observable system that manifested precisely the features called for by the PSSH. But it was not located in a central symbol processor, it was distributed across the members of the team, the devices and artifacts they manipulated, the procedures they followed, the channels of communication over which they passed messages, and the social organization of the ship.

This left unanswered the question: What IS inside the navigators? It did not seem likely to me that the PSSH provided a good account of what was happening in the minds of the members of the navigation team. As I wrote up these navigation studies in Cognition in the Wild (Hutchins, 1995), I struggled to articulate how one might model the internal cognitive processes of the navigators. In chapter five of Cognition in the Wild, I argued that some sort of connectionist system was a better fit to individual cognitive processing than the PSS is. I designed and implemented some computational simulations that modeled individual cognitive function as connectionist constraint satisfaction networks. I constructed communities of such individuals to illustrate how the decision-making properties of a community as a whole could be changed by changing the patterns of interaction among the individual agents without changing their internal properties at all. This has implications for real-world activities such as jury decision making, for example.

Then, in chapter 7 of Cognition in the Wild, I addressed the individual cognitive function of learning in context. I created a clumsy thought experiment to explore how a written procedure might be learned if the learner had learning properties like those of a certain class of connectionist network. One network might learn the sequence of words in the procedure. Another network could learn the sequence of meanings of the words. Yet another network could learn the sequence of actions described by the meanings of the words in the context of the sensed local setting. These networks would each sense the world and pass constraints to the other networks.

At that time, many pieces of that puzzle were still missing. As far as I knew, the kinds of networks I needed did not exist. Little was known about interactions among multiple networks working simultaneously on a single problem. The system of networks and processes I imagined in the early 1990s was already multimodal, and in retrospect, I see that feature of the model as prescient. The sort of network I needed then now exists as a predictive processing system.

From the modern perspective, I can look back and see what was lacking in the model I imagined 30 years ago. It did not exploit a generative computational framework, nor did it maintain continuous coupling to its environment. Those are elements that have only become available in computational systems of the last two decades. It is only now, in the mid-2020s, that I think I am able to sketch an answer to the question of what a model of individual cognitive function should look like. And that is one aim of this paper.

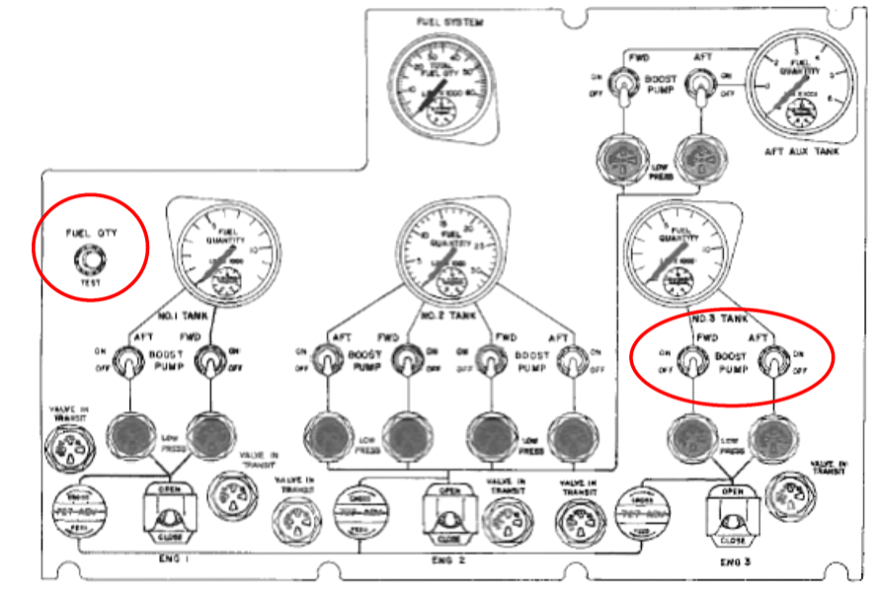

2.3. Airline Operations

3 From the late 1980s until 2016, my research village was the worldwide community of airline pilots. The cockpit of an airliner is a distributed cognition system, much like the bridge of a ship - except it is moving a lot faster. The papers titled "Distributed cognition in airline cockpit" (Hutchins & Klausen, 1986) and "How a cockpit remembers its speeds" (Hutchins, 1995b) are examples of the application of the distributed cognition approach to this domain.

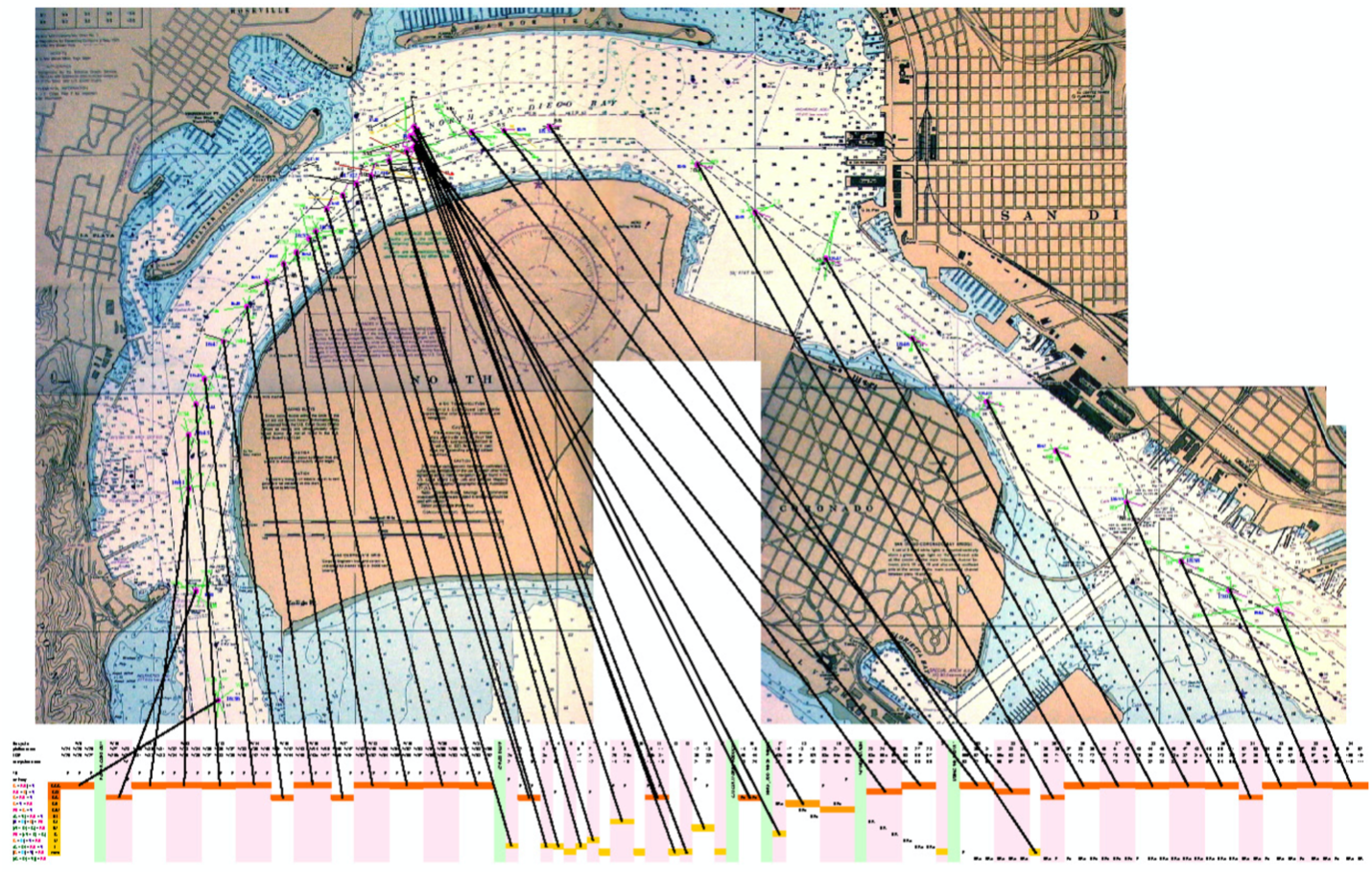

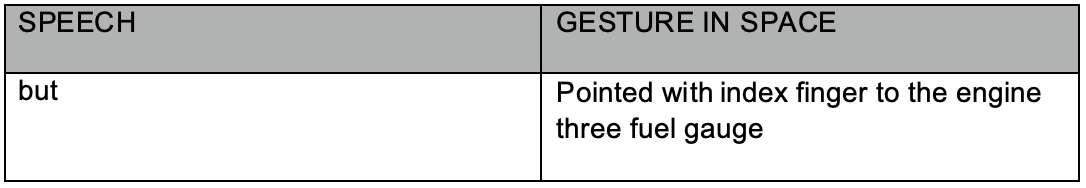

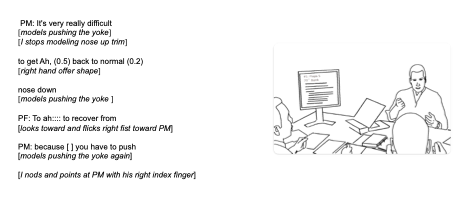

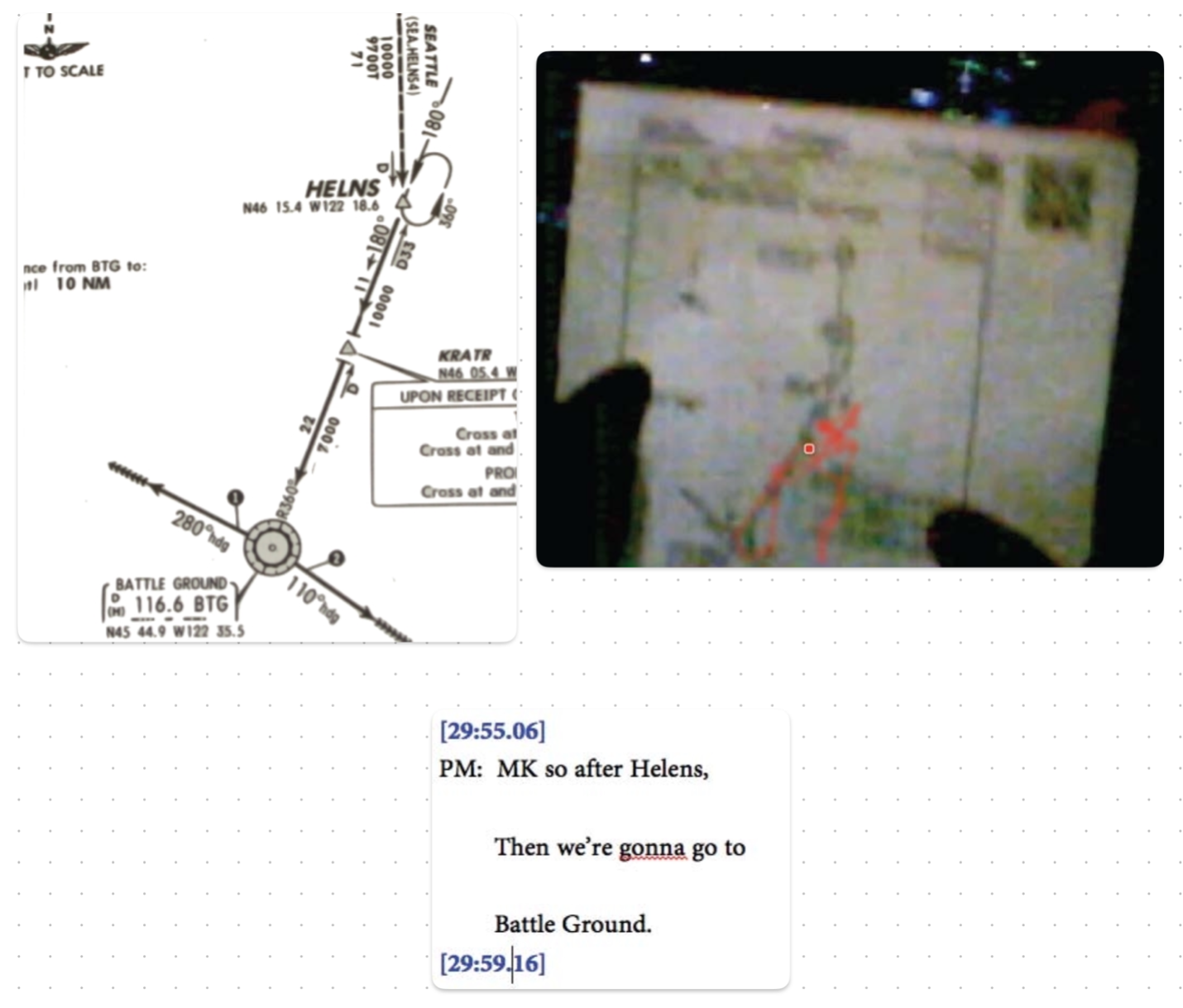

Figure 2.3. Briefing the approach to Christchurch, New Zealand in a Boeing 737

Photo by the author

Through arrangements with NASA, Boeing, Airbus, and many airlines around the world, I made observations in the flight decks of airliners on hundreds of revenue flights. My research team and I interviewed pilots and took still photos of them at work in the cockpit. We made video recordings of activities in flight simulators. We investigated and contributed to the design of flight deck instrumentation, operating procedures, and training programs. Employing (and enjoying) the participant observation aspect of traditional ethnography, I earned a commercial pilot license with qualifications in the first commercially successful airliner, the Douglas DC-3, and in two modern business jets. I also completed the training in the Boeing 747-400 (at Boeing in 1991) and the Airbus A320 (at America West Airlines in 1995).

Our investigations of flight crew activity are grounded in an ongoing long-term cognitive-ethnographic study of commercial aviation operations (Holder & Hutchins, 2001; Hutchins, 2007; Hutchins et al., 2006; Hutchins et al., 2009; Hutchins et al., 2013; Hutchins & Holder, 2000; Hutchins & Klausen, 1986; Hutchins & Nomura, 2011; Hutchins & Palen, 1997; Nomura et al., 2006; Palmer et al., 1993; Weibel et al., 2012). This ethnographic background allows us to interpret expert action and to ensure the ecological validity of our studies in high-fidelity flight simulators. There were many interesting objects of scrutiny in the domain of commercial aviation. My principal focus was the ways that flight crews understood and interacted with the automation in modern cockpits.

Over the course of the three decades I spent studying flight deck operations, methods and theory were changing rapidly. Methodological innovation included advances in the instrumentation of activity. The advent of inexpensive digital video brought a major change for all analysts of real-world activity and spurred the development of the behavioral science fields that focus on activity and interaction. Navigating in digital video is qualitatively different from using videotape. Using videotape, it is possible to compress time by moving fast-forward or -back, but time is still a continuous function of distance on the physical tape. Digital video provides wormholes through space-time. Moving from any temporal location in the recording to any other location is essentially instantaneous. Indexing is automatic, as every frame can be identified by its timestamp. Sensor technology has also advanced with motion capture and mobile physiology measures.

In the laboratory I shared with James Hollan at UCSD, we developed a Digital Ethnographer's Workbench. This included a set of digital tools to support the collection and analysis of field observations. For example, we created digital field notes with hyperlinks to digital scans of all the documents used by the flight crew.

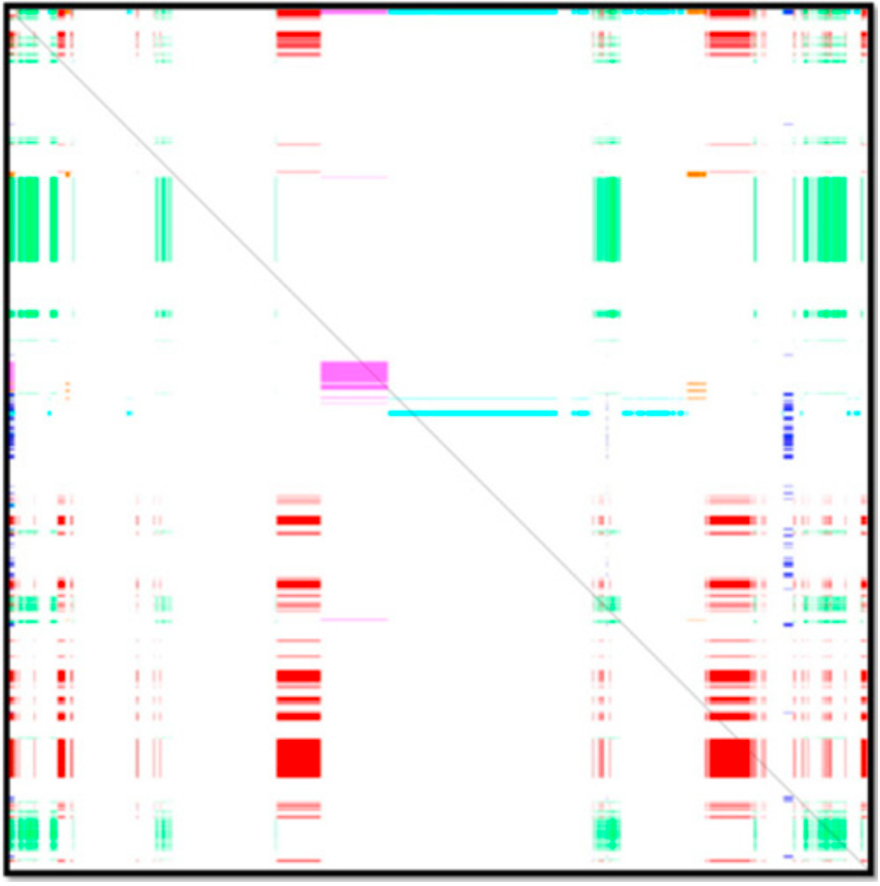

Culturally elaborated real-world activity typically involves multiple operators in interaction with one another and with complex technical systems. Our object of study is therefore complex, multiparty, multimodal, and socio-technical. Taking advantage of 70 years of development of sophisticated virtual reality environments, we instrument high-fidelity flight simulators and record the behavior of qualified flight crews in near-real-world situations. Modern sensor technology makes it possible to measure an unprecedented number of features of activity in such systems. However, the proliferation of measurements creates its own problems. Synchronizing and visualizing the relations among multiple data streams are difficult technical problems. Navigating rich data sets is difficult because of the sheer amount of data that must be managed. Data set navigation can be facilitated by good annotations and metadata, but providing even minimal annotation in the form of a timeline of events is a daunting and expensive task.

One of Jim Hollan's students, Adam Fouse, created an application called ChronoViz that provides solutions to many of the problems of measuring, analyzing, and visualizing the behavior of people in interaction, including airline flight crews (Hutchins et al., 2013). I will describe ChronoViz in more detail below in connection with the analysis of a few seconds of activity in a simulated Boeing 787 flight deck. At this point, let me just mention that ChronoViz supports the temporal alignment of multiple data streams. Timelines of key events can be generated and displayed within minutes of the conclusion of a simulator session. The entire data set can be navigated via any of the representations of any of the data streams. A great deal remains to be done, but we believe we have taken some important first steps toward using computational methods and good interface design to break through the analysis bottleneck created by the need to hand-code complex multimodal data sets.

2.4. Contributions of Cognitive Ethnography to Cognitive Science

In the new century, frameworks for understanding cognition changed too, with the rise of the fields I mentioned in the introduction that focus on the interaction of a person with their settings. Because no field or discipline has yet taken ownership of cultural-cognitive ecosystems, little is known about their function. Truly understanding how such systems work will require a large and sustained cognitive ethnographic endeavor.

3. Related Fields

4 Over the past three decades, cognitive science has been shifting from a concept of cognition as a logical process to one of cognition as a biological phenomenon. As more is learned about the biology of human cognition, the language of classical cognitive science, which described the cognition of socio-technical systems so well, appears increasingly irrelevant to internal cognitive processes. As Clark put it,

Perception itself is often tangled up with the possibilities for action and is continuously influenced by cognitive, contextual, and motor factors. It need not yield a rich, detailed, and action-neutral inner model awaiting the services of "central cognition" so as to deduce appropriate actions. In fact, these old distinctions (between perception, cognition, and action) may sometimes obscure, rather than illuminate, the true flow of events. In a certain sense, the brain is revealed not as (primarily) an engine of reason or quiet deliberation, but as an organ of environmentally situated control. (Clark, 1998, p. 95)

Several approaches strive for an understanding of the nature of human cognition by taking seriously the fact that humans are biological creatures. All of these provide some useful conceptual tools for understanding real-world cognition.

Ecological psychology (Gibson, 1986) focuses on psychological phenomena as properties of animal--environment systems. To understand perception, one must understand the properties of the world to be perceived. To understand action, one must understand both the motor systems and their interactions with the world. A synergistic relationship grew up between ecological psychology and the development of the dynamical systems approach to cognition. The dynamicists emphasize that the system that matters is the brain, body, and world coupled in motion (Kelso, 1995; Port & van Gelder, 1995; Spivey, 2007; Thelen & Smith, 1994), while ecological psychologists have borrowed analysis tools from dynamical systems theory (Kugler & Turvey, 1987). Such accounts have successfully modeled many perceptual and motor processes. However, it is not clear whether high-level cognitive processes can be captured by more of the same kind of process. The heterogeneous nature of real-world human action is a continuing challenge for dynamical system models.

Organism--environment dynamics become agent--environment interactions in embodied robotics (Beer, 2008). These efforts explore the ways that robotic agents can take advantage of structure in the environment to do thinking without representation (Brooks, 1991). For example, Brooks implemented simple robots that could autonomously navigate a setting. A low-level layer of control was designed to avoid objects. It is easy to build a robot that senses obstacles and turns away when one is encountered. This can be done simply by arranging the wiring that connects sensors to the motor system. No representations are needed. It is also easy to build a robot that can move to a particular distant visible target. Again, this can be done without representation. As Brooks says, "The second layer injected commands to the motor control part of the first layer, directing the robot towards the goal, but independently, the first layer would cause the robot to veer away from previously unseen obstacles. The second layer monitored the progress of the creature and sent updated motor commands, thus achieving its goal without being explicitly aware of obstacles, which had been handled by the lower level of control" (Brooks, 1991).

As the points of contact between organism and environment come to be seen as loci of essential processes rather than as barriers and boundaries to be crossed, the role of the body in thinking comes to the fore. These ideas are explored in two related contemporary approaches to cognition. In Europe, this is known as enaction. In North America, the embodied cognition perspective covers similar ground but from a different intellectual background.

The enaction perspective combines the philosophy of phenomenology (Dreyfus, 1982; Heidegger, 1962; Varela et al., 1991) with the cybernetic approach that appeared in the ecology of mind approach (Bateson, 1972; Dupuy, 2000). Building on the biological concept of autopoiesis (Maturana & Varela, 1987), the enaction perspective emphasizes that environments are not pre-given but are, in a fundamental sense, created by the activity of the organism (Havelange et al., 2003). The processes of life and those of cognition are tightly linked in this view (Thompson, 2007). Organisms are not passive receivers of input from the environment but are actors in the environment such that what they experience is shaped by how they act. Many important ideas follow from this premise. Maturana and Varela (1987) introduced the notion of "structural coupling" between an organism and its environment. This describes the relations between action and experience as they are shaped by the biological endowment of the creature.

Gibson's insight that perception is a form of action provided inspiration for a part of the philosophy of embodied mind movement (Hurley, 1998; Rowlands, 2006). For these authors, perceptual experience is grounded in regularities in the relations between sensation and action. These approaches view organism--environment relations in terms of coupling, coordination, emergence, and self-organization, rather than the transduction of information across a barrier. Noë (2004) says that perception is something we do, not something that happens to us. Thus, in considering the way that perception is tangled up with the possibilities of action, O'Regan and Noë (2002) introduced the idea of sensorimotor contingencies. In the activity of probing the world, we learn the structure of relationships between action and perception. These relationships capture the ways that sensory experience is contingent upon actions. Each sensory modality has a different and characteristic field of sensorimotor contingencies.

Embodiment is the premise that the particular bodies we have influence how we think. The rapidly growing literature in embodied cognition is summarized in Gibbs (2006) and Spivey (2007). Embodied cognition grounds high-level conceptual processes in bodily experiences (Barsalou, 2010; Calvo & Gomila, 2008; Johnson, 1987; Lakoff & Nuñez, 2000; Pfeifer & Bongard, 2007). One of the virtues of this approach is that emotion finds a natural connection to conceptualization through processes in the body. A subfield of embodied cognition examines the relations between gesture and thought (Goldin-Meadow, 2003; McNeill, 2005). Gesture studies highlight the coordination of talk with bodily action, demonstrating the multimodal nature of communication

Interactions between persons and their environments often simultaneously engage several modalities, speech and gesture, for example. It is now clear that inside the brain as well, the causal factors that explain the patterns seen in any one modality may lie partly in the patterns of other modalities. In fact, recent work suggests that activity in various cortical areas (e.g., visual and motor cortex, or visual and auditory cortex) unfolds in a complex system of mutual causality (Gallese & Lakoff, 2005; Sporns & Zwi, 2004; Wilson et al., 2004). Neuroscientists have thus become aware of the need to expand the boundaries of the unit of analysis to consider a wider cognitive ecology. In a review of psychophysiological methods Kutas and Federmeier say, ''...the complexity problem presented by the mind--brain--body system may require new ways of thinking about the kinds of measures we use and need to use because, in fact, the mind arises in a physical system that is distributed over space and time (Kutas & Federmeier, 1998).

Embodied cognition has its roots in psychology and is investigated mostly using experimental methods. The field of embodied interaction grows out of conversation analysis and linguistic pragmatics. It takes a more ethnographic approach to multimodality (Streeck et al., 2011). As the name implies, embodied interaction focuses on how people use their bodies in coordination with features of the social and material setting while interacting with one another. This is a bigger topic than the interactions of a single organism or person with a local environment, and it deals with concepts that are further from the organism-environment interface. Interactions among people are often carried out in public. To the extent that interaction can be read as a form of cognition, this is "cognition as public practice" (Streeck et al., 2011, p. 3). It is a form of cognition that can be recorded and analyzed.

The notion of semiotic resource is a core concept of the embodied interaction approach. This is nicely broader than the idea of external representation, although the so-called external representations can be seen as a subset of semiotic resources. A semiotic resource is an object, pattern, or event in the world that comes to have meaning for the participants in an activity/interaction. Words can be semiotic resources, of course, but so can gestures, facial expressions, and features of the material world. Researchers in this area speak of the mutual elaboration of semiotic resources. The phenomenon of environmentally coupled gesture is a prototypic case of this mutual elaboration. Goodwin analyzes an interaction between an archaeologist and a student who are examining discolorations in the dirt of an excavation.

"... by itself, the talk is incomplete both grammatically and, more crucially, with respect to the specification of what the addressee of the action is to attend to in order to accomplish a relevant next action. Similarly, the embodied pointing movements require the co-occurring talk to explicate the nature and relevance of what is being indicated. .... By itself each individual set of semiotic resources is partial and incomplete (Agha, 2007; Goodwin, 2007). However, when joined together in local contextures of action, diverse semiotic resources mutually elaborate each other to create a whole that is both greater than, and different from, any of its constituent parts (Goodwin, 2000)." (Streeck et al., 2011).

As more complex interactions are considered, the universe of semiotic resources grows so that, beyond mutual elaboration of two or three resources, we encounter the inter-elaboration of many semiotic resources, including those found in speech, body, activity, and setting.

Sequential organization is central to the way action is understood by participants. Conversational turns always build on what has come before. I imagine this to be a recursive process in which the meaning of utterance N depends on the meaning of utterance N-1, which in turn depends on the meaning of utterance N-2, and so on to the beginning of the conversation or to the limit of local memory. The process of constructing an interaction is dynamic. Speakers sometimes change the structure of a sentence while it is being constructed. Interactants can shift the meanings of their own and others' utterances by what they subsequently put in play, so that the meaning of utterance N may also depend on the meaning of utterance N+1.

The modalities in embodied interaction occupy a different level of description from the modalities of ecological psychology or dynamical systems. In embodied interaction, the modalities are gesture and talk, of course, but also environmentally coupled gesture, facial expression, body posture, how participants orient to one another, and how they position themselves in the setting and with respect to various semiotic resources.

One of the key insights of the embodied cognition framework is that bodily action does not simply express previously formed mental concepts; bodily practices, including gestures, are part of the activity in which concepts are formed (Alač & Hutchins, 2004; Gibbs, 2006; McNeill, 2005). That is, concepts are created and manipulated in culturally organized practices of moving and experiencing the body. Similarly, gesture can no longer be seen simply as an externalization of already formed internal structures. Ethnographic and experimental studies of gesture are converging on a view of gesture as the enactment of concepts (Goldin-Meadow, 2003; Núñez & Sweetser, 2010). This is true even for very abstract concepts. For example, studies of mathematicians conceptualizing abstract concepts such as infinity show that these, too, are created by bodily practices (Lakoff & Nuñez, 2000).

I lack the space needed to sort out the many strands of this literature. Let us simply note here that according to the embodied perspective, cognition is situated in the interaction of body and world, dynamic bodily processes such as motor activity can be part of reasoning processes, and so-called "offline cognition" is body-based too. Finally, embodiment assumes that cognition evolved for action, and because of this, perception and action are not separate systems but are inextricably linked to each other and to cognition. This last idea is a near relative to the core idea of enaction.

Both embodiment and enaction stress the tight relation between thought and action (Alač & Hutchins, 2004; Hutchins, 2010b). Enaction shares with the dynamical systems approaches a commitment to circular rather than linear causality, self-organization, and the structural coupling of organism and environment.

Cognitive grammar (Langacker, 1987) and conceptual blending (Fauconnier & Turner, How We Think, 2002) are cognitive linguistic theories that describe phenomena that fit poorly with the theory underpinning mainstream cognitive science at the end of the 20th century. The predictive processing approach is much more congenial to these approaches.

Cultural Historical Activity Theory, with its emphasis on the social construction of thought, inspired other approaches that consider the cognitive consequences of social and cultural configurations (Daniels et al, 2007). Activity theory is the direct ancestor of the situated action perspective (Greeno & Moore, 1993; Lave, 1988; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Rogoff, 2003; Suchman, 1987). With its emphasis on the interconnections of developmental processes on all timescales (phylogenetic, cultural, ontogenetic, and micro-genetic), activity theory has been put to work by educational researchers as well (Greeno, 1998; Pea, 1996).

The rise of connectionism not only transformed theories of internal mental processes, but it also spawned a wider investigation of emergent phenomena at the supra-individual level. There is a growing literature on computational models of social and cultural systems. The emergence of language from interactions among agents is a particularly interesting area of research (Cangelosi & Parisi, 2002;Hazlehurst & Hutchins, 1998; Hurford et al., 1998; Hutchins & Hazlehurst, 1995, 2002; Hutchins & Johnson, 2009).

The field of collective intelligence focuses on the organizational principles that determine the cognitive properties of groups (Malone & Bernstein, 2015; Sunstein, 2007; Surowiecki, 2004). Barbasi(2002) describes powerful regularities that explain how patterns of connectivity can change the cognitive properties of a network. The subtitle of Barbasi's book is ''How everything is connected to everything else and what it means for science, business, and everyday life." While everything is connected to everything else, the patterns in the density of interconnectivity determine cognitive properties of the system, whether the system is an area of a brain or a group of governmental agencies responding to a crisis.

4. Framework

Guided by the findings of the related fields described in the previous section, I assume that every moment of human experience is multimodal, generative, and continuous (MGC). The theoretical instantiation of PP supports the generative aspect of this formulation.

In this section, I outline a theoretical framework that integrates these three aspects of cognition. I will use this framework as a guideline for creating descriptions of ongoing activity. It will guide our looking. The framework is multimodal in the sense that it includes all of the sensory and motor modalities. It is generative to capture the power of recent advances in generative AI to model some aspects of intelligent behavior. And it is continuously coupled to the sensorimotor surfaces, and via those surfaces, continuously coupled to the body and the world. The generative component is the heart of the model. This is imagined to be a connectionist network loosely modeled on a predictive processing system.

Predictive processing (PP) networks have three instantiations. There is a Theoretical Instantiation of PP, which is a description of an imaginary network of units. This theoretical instantiation is a computational framework that was inspired by a combination of a theory of physical thermodynamics (the Boltzmann machine) and by brain function. It was, as they say, 'neurally inspired', so, to the extent that it is accepted that the brain is a PP system (and Andy Clark's (2023) book provides ample evidence that this is so), a second instantiation of PP is an actual network of neurons implemented in meat. Let's call this the Biological Instantiation of PP. The theoretical instantiation of PP has also been given multiple implementations in silicon. These computational instantiations are what we now know as Generative Artificial Intelligence (genAI). Let's call these the Artificial Instantiations of PP. One of the challenges of writing about this area is that in popular discourse, these instantiations are often conflated, and this conflation causes a good deal of confusion.

The very name Artificial Intelligence implies a claim to a particular relationship between the computational implementations and human intelligence. Most researchers in cognitive science take intelligence to be a property of the brain. This claim is strongest when the computation is implemented in neurally inspired networks. In both cases, genAI and the brain, the work is done by vectors of numbers. Both kinds of systems are composed of huge numbers of vectors that are very cleverly arranged and connected, constraining and responding to the constraints of one another. The vectors of numbers are implemented differently in neurons, in one case, and transistors in the other, but it's all just vectors of numbers in either case.

My interest is in theoretically hypothesized PP networks. It would be nice if theoretical PP networks were an accurate description of brain function, although, of course, now in the mid-2020s, they are still lacking many important aspects of nervous system operation. It is certain that no currently implemented computational version of PP is fully faithful to human cognitive function. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the PP component of the framework I describe below is neither the brain nor is it any currently implemented version of generative AI.

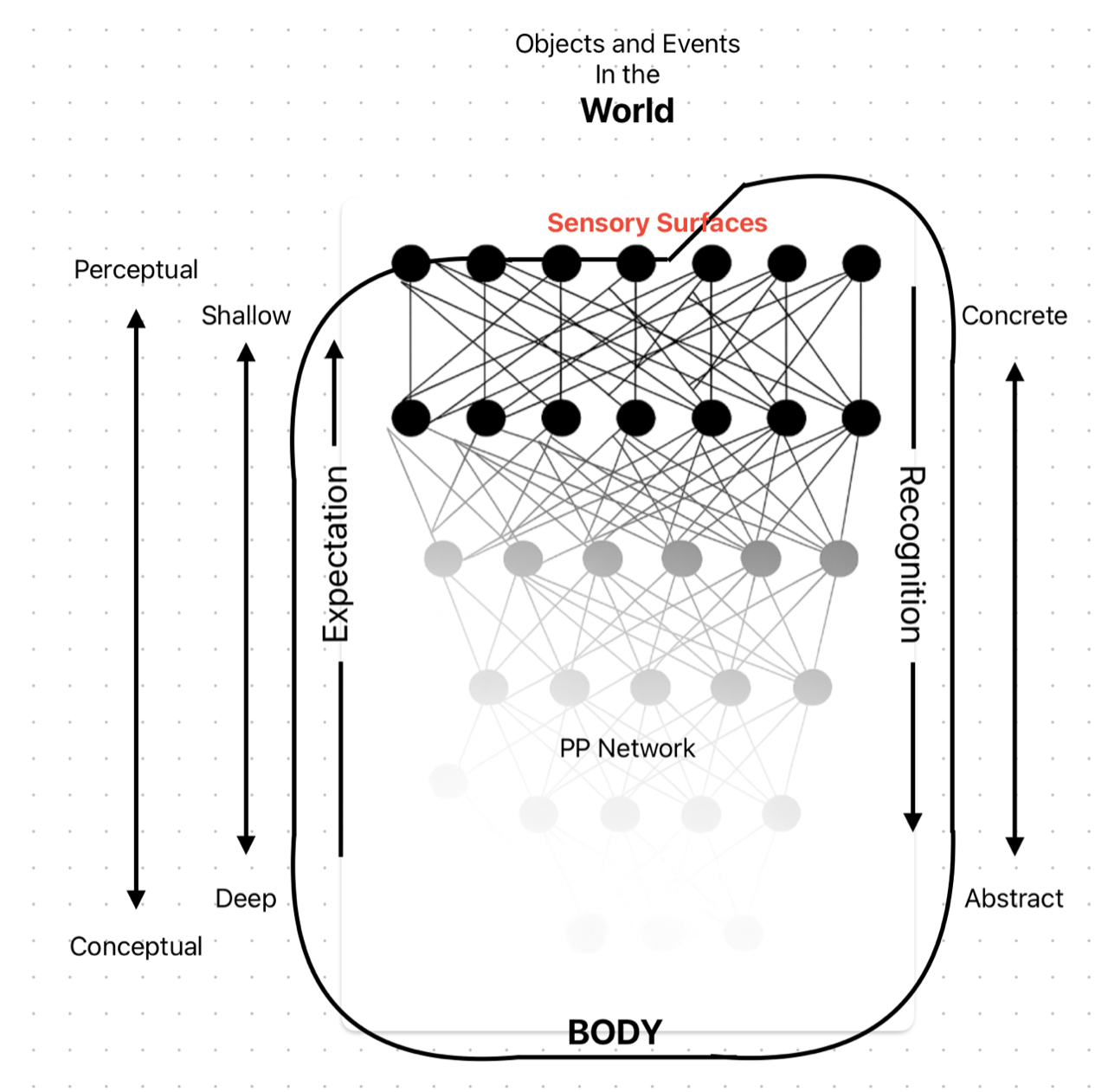

Figure 4.1. A sketch of the MGC system

This is my sketch of a theoretical instantiation of the MGC system. It is not intended as a biological instantiation, although it borrows some concepts from neuroscience. It is not intended as a computational instantiation, although it borrows some concepts from generative AI. It is not strictly a predictive processing instantiation, although it borrows from that line of research as well, especially as it is presented by Andy Clark (2023). The diagram is grossly oversimplified, of course. The human brain is estimated to have around 90 billion neurons and has a complex architecture of regions.With this sketch, I only intend to suggest a few key functional relationships between the world, sensory-motor surfaces, and a very large neural network. It is these imagined relationships that guide our examination of real-world activity.

The body is in the world. The body contains a PP network. At the top of the PP network are layers that comprise the sensorimotor surfaces. These layers of the PP network are simultaneously in the network - shaped by their connections to layers below - and in the world - shaped by the physics of the world that impinges upon them. Below the layers that comprise the sensory surfaces is a deep connectionist network. The upper layers of the network that lie near the sensorimotor surfaces are associated with particular sensory or motor modalities covering both exteroception and interoception.These layers encode concrete features of the flow of sensation or action.

Deeper layers encode more complex features. For example, consider the representation of objects in various spatial frames of reference in the human visual system. There is a progression of spatial representations from shallow to deep as follows: Retino-centric - head-centric - body-centric - allocentric. Each successive representation in this sequence integrates more contextual information than its predecessor. The retino-centric frame of reference is modality specific. It answers the question, where is the object on the retina of the eye? The deeper representations appear in layers that have connections to other layers. They constrain, and are constrained by, the patterns of activation on other layers. The head-centric frame of reference, for example, requires coordination of the retino-centric representation with proprioceptive information about the orientation of the head. A body-centric representation occurs deeper in the network and requires the head-centric representation plus additional information from other sense modalities concerning the relationship of the head to the body. Allocentric spatial representations occur even deeper in the network as they require a representation of the space around the person in addition to representation in the other frames of reference.

Thus, while shallow layers encode features of the patterns of activation on the sensorimotor surfaces and are modality specific, deeper in the system are layers that span modalities. This is where the modes interact with one another. It is the realm of sensorimotor contingencies, hand-eye coordination, motor resonance, mirror neuron phenomena, and many more multimodal effects. Even deeper in the network are layers that encode abstract concepts.

Layers hold patterns of activation as internal structure. Layers are connected to one another by connective tissues that hold patterns of influence as internal structure. The connective tissues carry influence from part of the pattern in one layer to a part of the pattern in another layer. The pattern of activation on any given layer is determined by the patterns of activation on the layers to which it is connected and by the patterns of influence in the tissue that connects them. Such a system can be described by configurations of activation across its layers. Inference (constraint from a shallower layer to a deeper layer) and generation (constraint from a deeper layer to a shallower layer) happen as the layers update their patterns of activation in accordance with the patterns of activation on the layers to which they are connected as mediated by the patterns of influence on the tissues that connect the layers.

The configuration of activation across all layers of the system at any given moment is known as the system state. As the system runs, the patterns of activation on the layers are updated. This means that the system transitions through states. This is how the relatively short-term changes of recognition and prediction happen. The entire inventory of possible states for the system is called its state space. For a given overall pattern of connective influence, each state will have a certain probability of occupancy. The operation of the system can be described as a trajectory or path through state space.

Learning in such a system happens by changing the patterns of influence on the tissues that connect layers. Changing these patterns of influence changes the state space of the system and changes the probability distribution across the states in the state space. What a generative network learns is to predict or reproduce its input. A PP network learns to predict the flow of sensorimotor experience. In order to predict this flow, a generative network must develop models of the processes in the environment that cause the flow of sensorimotor experience. This sounds incredible, but it works. I will have more to say about this in the section below discussing the Generative aspect (G) of the MGC system.

Notice the shallow/deep spatial metaphor. This depth dimension maps roughly onto content properties. Shallow layers encode specific, concrete features, while deep layers encode general, abstract concepts. In this diagram, sensorimotor surfaces are at the top, and deep layers of conceptual organization appear lower in the figure. This orientation reflects the grounding of cognition in action and perception rather than in abstract computation. Constraints that shallow layers exert on deeper layers implement inference, encoding, classification, and recognition. The constraints that deeper layers impose on shallower layers are the generative influences of decoding, expectation, and prediction.

This is an inversion of conventional network diagrams, which typically put abstract concepts and general category names at the top with sensorimotor processes at the bottom. I have flipped the network for several reasons. First, it puts sensorimotor processes at the top of the diagram where they are perceptually salient for you, the reader. I want to do this to counter the implicit devaluation of sensorimotor processes in mainstream cognitive science. Second, it constructs a frame of reference in which layers near sensorimotor layers are 'shallow' and encode features, while conceptual layers are deep (rather than high). This will be useful to me later when I discuss the idea that language phenomena operate in 'shallow' symbols. Third, in this scheme, generative influence is oriented upward (that feels right), and inference is downward.

The Internal structure of the Imagined system is a complex, partially reconfigurable architecture. For our purposes, the details of this architecture will remain unspecified. The designers of generative AI systems know the general arrangement of the layers in the networks, but they do not know the details of the wiring (the learned connections among the layers of units) of the system after it has been trained. Neuroscience has made strides in mapping the architecture of the brain, but much remains to be learned.

There are limits on what we can know about the internal functioning of such networks beyond the fact that they learn to predict the statistical regularities of their environment. Suleyman and Bhaskar, describing contemporary generative AI systems said,

"In AI, the neural networks moving toward autonomy are, at present, not explainable. You can't walk someone through the decision-making process to explain precisely why an algorithm produced a specific prediction. Engineers can't peer beneath the hood and easily explain in granular detail what caused something to happen. GPT‑4, AlphaGo and the rest are black boxes, their outputs and decisions based on opaque and impossibly intricate chains of minute signals." (Suleyman & Bhaskar, 2023, p. 149)

There is no way to know in detail how any particular prediction was created by either a brain or a generative AI system. When studying either the biological or artificial instantiation of the predictive processing system, it is possible to observe and document the regularities in the flow of experience that these systems must predict. It is even possible to determine where activation is highest under certain task demands, as is done in brain imaging studies. But it is not possible to know in detail how any particular prediction or action arose. In any case, I am developing a theoretical model and am not making a commitment to any particular artificial or biological instantiation of a network system. Even without committing to details, it is possible to sketch a generic description that applies to most instantiations of generative networks but commits to none.

In this scheme, there is no separate downward and upward pass. The separation of passes is a feature of digital computational implementations. Instead, I imagine this theoretical system to operate through a single settling process in which constraints propagate continuously in all directions. The system simultaneously recognizes (downward) and generates (upward) the patterns of sensory activation. The entire network is in continuous resonance with the patterns of activity on the sensorimotor layers. The patterns of activation on the sensory surfaces are constrained simultaneously by the world, via the body, and by the dynamics of the entire deep network. I will have more to say about this continuous operation in the sections below.

4.1. Multimodal

The two perspectives on embodiment described in the related fields discussion produce two distinct kinds of multimodality. Each implies ways of speaking about modalities and the relationships among modalities as well as a typology of modalities. What counts as a mode in a multimodal system depends on whether one focuses on intra-individual function or on interactions among individuals.

The embodied cognition perspective and predictive processing build theory around the intra-individual functioning of a single organism. They focus on how sensorimotor processes are integrated into internal systems. In addition to the usually considered senses of vision, audition, touch, taste, and smell, we experience our own bodies via proprioception. We monitor the position and motion of our limbs. Our vestibular system keeps track of accelerations, including that of Earth's gravitational field. We sense how much muscle tension we apply to hold a position or to move. There are also what are known as interoceptive senses that monitor our internal bodily states, hunger, thirst, heart and respiration rates, blood pressure, pain, the states of our internal organs, and so on. Among our motor modalities are the control of skeletal muscles, voluntary and otherwise. Largely out of awareness, we also sense the body motion involved in speech, eye position and movement as well as the internal muscles that accomplish swallowing, and peristalsis.

In addition to sensory and motor modalities, we have deeper encodings of experience that integrate information from multiple sensory and motor modalities. The encoding of space is probably the best understood in terms of these deeper encodings. Spatial encodings integrate information from visual, auditory, and proprioceptive modalities. These may be egocentric, based on the own body or parts of the body such as the eye, head, and hand. Spatial coordinates may also have an allocentric (external) frame of reference.

Sensorimotor contingencies describe relations among modalities. But there are more subtle effects as well. For example, Smith (2005) shows that the perceived shape of an object is affected by actions taken on that object. Motor processes have also been shown to affect spatial attention (Engel, 2010; Gibbs, 2006, p. 61). Thus, we should expect that embodied, multimodal experiences are integrated such that the content of various modes affect one another.

In contrast to the embodied cognition approach, the embodied interaction perspective (Streeck et al., 2011) builds its theory around inter-individual processes, examining interactions among persons engaged in joint activity. This field identifies the communicative modalities: talk, gesture, facial expression, body posture, as well as features of the setting. It also explores super-segmental features of talk such as prosodic structure, tempo, rhythm, etc.

Most of the modalities identified in embodied interaction are already richly multimodal in the embodied cognition perspective. The production of speech involves motor, auditory, and conceptual processes. Other modalities may be involved as well, depending on the topic spoken about, as in the case of discussing the perception of odors or flavors, for example. The production of gesture involves motor, proprioceptive, and sometimes visual processes.

One of the relationships among modal contents highlighted by embodied interaction uses the phrase "mutual elaboration of semiotic resources." This is shorthand for something more complex that gives us an additional window into the relations between the modalities of embodied cognition (vision, audition, proprioception, etc.) and the modalities of embodied interaction. For some object or event in the environment to be a semiotic resource requires that its impression on the sensory surfaces be coupled to and predicted by a generative network. It is this coupling that produces the meaning of the semiotic resource. Some object or event is a semiotic resource when its impression on the sensory surfaces is incorporated in a dynamic activation configuration such that it is seen as having a particular meaning. This dynamic activation configuration is the meaning of the semiotic resource. It is how the resource is seen as having a particular meaning.

When two semiotic resources mutually elaborate each other, the elaboration happens, not in the world of objects and events, but in the networks in which the semiotic resources are embedded. The networks pass each other activation. They have a relationship of mutual excitation. They may be entwined with each other, sharing some layers or segments of layers of network units.

Both the embodied cognition perspective and the embodied interaction perspective emphasize the fact that, while it is possible to separate modalities for the purposes of analysis, in fact, multiple modalities are almost always integrated in action. As we will see in the vignettes below, the relations among the contents of modalities, whether within or between persons, can be functionally important. Multiple modalities with congruent contents may mutually reinforce one another, providing stable representations. When the contents of the modalities are complementary rather than congruent, relations among modalities can be sources of variation in adaptive processes.

4.2. Generative

When it is read as a metaphor for processing in the brain, the generative system is coupled to a flow of sensory evidence, which it recognizes and predicts. There are many generative formalisms. I am not committed to anyone. All of the instantiations of predictive processing are composed of a deep hierarchy of layers of units with sensory and motor processes at the surface levels. Sensation projects downward through the layers of units while prediction projects upward toward the surface. Learning processes tune the connections among layers to bring the upward projecting predictions of each layer into agreement with the patterns of activation on the layer above.

The system learns the structure of the flow of sensation and uses what it has learned to predict not just the flow of sensation, but the elements of the learned structure that are implicated in the generation of the predictions of sensation. These are the so-called "models of the hidden causes of the flow of sensation." From the point of view of the predictive processing agent (or experiencing person), only the flow of sensation and the models of its causes are available. The events and processes in the world that cause the flow of sensation are not observed by the agent; this is why they are said to be "hidden" from the agent. In learning to predict the flow of sensation, a predictive processing system must create internal processes that model or simulate the operation of these hidden causes.

In order to generate predictions that match sensation, the generative aspect of predictive processing must create a model of the workings of the world that produced the sensations. That is, a model of causes in the environment. The models of hidden causes are representations, but they do not represent the causes in any way that would be recognizable to an analyst or to the experiencing person. This is representation without resemblance. Nor is there any requirement that the models of hidden causes be correct, true, or veridical. They can be completely fictional as long as they efficiently predict the flow of sensation. The generative system is simultaneously active, predicting the contents of multiple modalities and doing so by simulating the hidden causes of those multimodal contents.

Clark (2023) distinguishes perception from sensation. Perception is sensation in the context of the network processes that predict it. Predictions change to better fit (reduce the difference from) the flow of sensory evidence. "To perceive is to find the predictions that best fit the sensory evidence. To act is to alter the world to bring it into line with some of those predictions" (Clark, 2023, pp. 212-213).

This generative capacity completes partial patterns, resolves ambiguities in sensed data, and imagines what "should be" even when the senses present something that should not be. As Andy Clark says, "There is a suggestive duality here such that to perceive the world (in this way) is to be able to imagine that world too - it is to be able to generate, using our inner resources alone, the kinds of neural response that would ensue were we in the presence of those states of affairs in the world" (Clark, 2023, p. 220).

This imaginative component is the source of confabulation (often incorrectly referred to as "hallucination") that is a cause for concern in generative AI chatbots. The chatbot may produce something that makes sense, given everything else it knows, but which is not true. The biological instantiation of PP is also subject to confabulation. Under some conditions, people may imagine familiar patterns when the senses carry no pattern at all. For example, Clark discusses a series of experiments in which primed subjects may report that they hear the melody of the song White Christmas when they are presented with pure noise (Clark, 2023, p. 23). I was tempted to say that people can imagine familiar patterns when the senses carry no discernible pattern. But, of course, the point here is that when a subject hears White Christmas in pure noise, they have discerned a pattern. It just happens to be a pattern that did not exist in the sense data. This is a simple illustration of the fact that discernment is an active generative process.

An important feature of the generative capacity of predictive processing is that it provides a natural explanation for the fact that people routinely experience useful patterns that go beyond what is suggested by the sensory evidence. For example, in the presence of a spatial array, we may perceive the array, and perceive additional culturally supplied structure superimposed upon the array. We can see a bunch of stars as a constellation with a definite shape. We may even imagine lines in the sky tracing a connection between the stars of the constellation. This "seeing as" is an essential cognitive process that is the basis of a large family of cultural practices. We can see a line of people as a queue. We can see a line drawn on a navigation chart as a projected ship's track. We can see an array of numbers as a sequence or a scale of numbers. The generative capacity allows us to project internally generated structure onto sensation to produce experience that has emergent properties that are not present in either the sensation or the projected structure alone. In concert with culturally constructed environments for action, this projection of structure is an incredibly powerful ability. As I will show in the vignettes below, it is a way to produce what have traditionally been known as high-level cognitive processes while deploying low-level perceptual processes in culturally organized settings.

With experience, expectations become structured. The expectation generator learns from experience to predict sensory evidence. "What matters for our purposes is just that the generative model - however installed - is a learnable resource that will enable a system to self-generate plausible new versions of the kinds of data seen in training" (Clark, 2023, p. 220). The generative system must produce predictions on multiple time scales and at different levels of specificity. Because expectations can appear at any depth of the network, they can be general or abstract so that a range of details can be accommodated without violating the expectation.

Active inference is the term introduced by Karl Friston and colleagues as a way of highlighting the unity of perception and action under schemes in which perception aims to find the predictions that best fit the world, while action aims to make the world (starting with simple bodily motions) fit the predictions. One imagines or predicts the movements that will accomplish some goal, and those imagined movements become a motor plan.