1. INTRODUCTION

Neither science nor politics alone will make Brazil win its war against COVID-19. The current Minister of Health, who supposedly (Benites, 2020) argues in favor of science, failed to prevent rapid and high rates of community transmission of the novel coronavirus across the country. The elected president is mainly concerned about political survival (Reuters, 2020). The Minister of Health needs to acknowledge fundamental containment and mitigation limitations the country faces in this pandemic. The president must admit that many challenges imposed by this virus will not be addressed by intuition or simply replicating foreign policies. The current national debate between evidence-based policy and anecdata will only prolong the exit to this unprecedented crisis (Ansell & Geyer, 2017; Pinheiro-Machado, 2020). On the one hand, the recency of and uncertainty (that is, unknown probabilities and outcomes) around this pathogen makes tackling it uniquely from a traditional scientific standpoint less effective (Aguilera, 2020; Lunn et al., 2020). On the other hand, the chances of prescribing a course of action that has not been sufficiently scrutinized could pose great health risks to those seeking treatment and quickly backfire (Jiang, 2020; Godin, 2020). In this context, this article argues that erratic institutions can incrementally (Feitsma, 2018, p. 9) improve governance during crises (Zeitlin, 2015, p. 9) by institutionalizing a straightforward reflective report format (Sen, 2010), verbal or written, among policy advisors. The expectation is that the incorporation of a methodology that favors critical thinking will help decision makers draw a more accurate picture of concerted actions to address wicked problems (Cabannes & Lipietz, 2018; Head, 2008; Pinto et al., 2018).

2. BACKGROUND

Brazil’s health minister waited until first reported cases in the country to come up with a plan to contain the spread of the new coronavirus (Lima, 2020). He also initially downplayed the effects of this epidemic. He said the Brazilians should wait and see how this virus would behave in warmer places (de São Paulo, 2020). Such a statement was made despite regions in the same latitude having already expressed growing concern about the chances of community transmission (Khalik, 2020). The slow response of the minister to contain this virus has significantly affected the capacity of the country to come up with containment strategies such as testing, tracking and isolating infected and suspected cases (Reeves, 2020).

In addition, the minister has apparently transferred the responsibility of his decisions to guidelines provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Falcão & Vivas, 2020). The WHO plays a key role in gathering and informing the international community about emerging health risks. However, it has been criticized for i) being slow in pandemic responses (Feldwisch-Drentrup, 2020), ii) deliberately ignoring key stakeholders (Mulier, 2020), and iii) proposing a policy ('test, test, test') (Wood, 2020) that is not feasible for ill-prepared countries. Brazilian public health authorities failed to prepare the country to carry out rapid, reliable, and mass testing (Barifouse, 2020). Thus, they cannot quickly identify cases and as a result track and link them to clusters. To make matters worse, the ‘Wuhan approach’ to enforce extensive and long lockdowns to suppress the spread of the virus is not feasible in large urban areas in Brazil due to the number of people living under the poverty line (Costa, 2020). If Wuhan-style lockdowns are to be enforced, the result would be chaos, like India has been witnessing (Bisht, 2020).

Also, the poor in Brazil, under the current welfare system, have already made it clear that they would rather die of respiratory-related illnesses than of hunger (Vespa, 2020). Therefore, the strategy to reduce the risk of mortality among the most vulnerable in Brazil needs to be adapted to the country's socioeconomic conditions (Dunn et al., 2020; Ghebreyesus, 2020). At the current rate of uncontrolled community transmission, this solution depends on a treatment or a still-distant vaccine (Fauci, 2020) to ensure Brazilians can safely return to 'normal life' while protecting the most vulnerable within their inner social circles. Until then, the national leader and his close advisors need to avoid that this health crisis turns into a devastating social and economic crisis (Albertus, 2020).

The Brazilian president has advocated the prescription of a contested medication to fight the disease (COVID-19) caused by the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) (Nacional, 2020). This claim follows the echoes of the U.S. president (News, 2020). However, the scientific community at large is cautious about prescribing such medicine due to lack of randomized controlled trials that verify the safety and effectiveness of such medicine to combat this respiratory disease (Piller, 2020). In Brazil, there has been anecdotal evidence that such medical treatment should be administered (de São Paulo, 2020). The Minister of Health and research institutes in the country, however, have been cautious about recommending this treatment to the public at large (Globo, 2020; Brasil, 2020). The minister, instead, has sided with the World Health Organization's mitigation policy of stay-at-home and social distancing as preferred methods to break infection chains (Resende & Matoso, 2020). The expectation is that such policies will momentarily bring infection rates down and thus reduce the chances of public health services collapsing due to the surge number of patients seeking hospitalization concomitantly (Jansen, 2020).

The president, however, argues that stay-at-home orders, as enacted by state governors, should be immediately halted (Nacional, 2020). He argues that losses in the economy are to cause more suffering to the country than the expected death of thousands of vulnerable individuals (U.O.L., 2020). The Brazilian society is as of now divided into following the president economic perspectives or complying with scientific reassurances (Estadão, 2020).

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The clash observed in Brazil illustrates to a certain extent the academic debate around evidence-based policy (Cairney, 2016; Easterly, 2016; Newman et al., 2017). Supporters of incorporating science into politics, despite its challenges (Newman et al., 2017), tend to argue that it is evidence (Costa et al., 2019), and not emotion, intuition, ideology, or isolated anecdotes, that should feed policymaking (Goerin et al., 2017). If an argument cannot be statistically supported and explained, it carries less weight for policy making (Liebman, 2013). Critics of this scientific method argue that the term 'evidence' itself is rather subjective since it fails to encompass the complexity of social phenomena (Cowen et al., 2017; Mullen, 2016; Rodriguez et al., 2017; Saltelli & Giampietro, 2015; Sinclair et al., 2021). In addition, skeptics argue that it is not uncommon for scientists to disagree even after enjoying plenty of time to collect and analyze large sets of data (Saltelli & Giampietro, 2017).

In the context of crisis management, this long-standing academic debate tends to become even more heated. In the context of the US, which has now the largest number of infections to the novel coronavirus and deaths to COVID-19 worldwide, the president and its main scientific advisor cannot agree over which direction the country is heading to (Haffajee & Mello, 2020; Post, 2020). This is because time is of the essence. Crises are extraordinary situations that demand immediate response with minimum, incomplete or no information whatsoever (Moynihan, 2008). In these moments, decision makers are elevated to a position that society looks up for coherent explanations and coordinated actions to reduce their anxiety over the effects of the unfolding event in their routines (Boin et al., 2016; Lazzarini & Musacchio, 2020).

It is not only limited time that decision makers are constrained by. They are also unable to process every piece of critical information that is given to them on a daily, or even hourly, basis (James & Wooten, 2010). This makes them resort to cognitive mechanisms that help them effortlessly organize and prioritize thoughts and interests (Kahneman, 2003). Values and beliefs shaped by decision makers' experiences are the variables that set in motion where and how each piece of information stacks up (Abers et al., 2013; Clandinin & Caine, 2013; Codato et al., 2015; Gauchat, 2015; Walsh, 2018). Humans, in general, seek comfort in messages that confirm our idiosyncrasies (Cook & Smallman, 2008). We try our best to avoid the psychological stress that conflicting information has on challenging our prior set of beliefs forcing us to review and shift preconceived courses of action (Brehm & Cohen, 1962). Public authorities tend to cognitively react to avoid penalizing their beliefs just as most people do (Carnielli, 2008).

Nevertheless, national leaders live under the public eye. They are not allowed to err as frequently as normal people do (Flyvbjerg et al., 2002). They must find ways to enhance their decision-making processes (Willems & Van Dooren, 2016). Consulting with experts from different fields about a particular issue during critical times can certainly help them in this endeavor (Alexiadou & Gunaydin, 2019). They could also momentarily gather a limited number of advisors that are thoughtful in their proposals and able to communicate effectively (Davidson, 2017; Walsh, 2018) to provide them with daily updates and recommendations. This deliberative process, however, can quickly become time consuming and unproductive (Scolobig et al., 2016). Thus, a structure guiding advisors to share opinions and help the decision maker easily grasp a myriad of viewpoints is highly desirable.

Reflective reports help advisors incorporate elements of critical thinking into their communication with the decision maker. Leaders often look for resourceful analysis (Koh, 2017). In the deliberative process proposed in this study, advisors are not expected to debate with other advisors (Martin, 2000). They are, instead, expected to outline their opinion in the most concise and simplest form (Clemson & Samara, 2013). While actively listening to each advisor, leaders should pay less attention to the argument itself than to assumptions, examples and generalizations advisors put forth. For instance, if a comparative example is brought up to substantiate an argument, leaders should ask themselves whether such comparison is valid in the first place. Also, anecdotal evidence can indeed be a sign of an emerging problem or solution (Parnell & Crandall, 2020). However, it is the rationality, especially scientific, supporting the significance of an outlier and the trade-offs that it ensues that must be carefully considered by the decision maker (Rosenthal & Kouzmin, 1997).

This paper, therefore, proposes that national leaders encourage advisors to expose the assumptions and limitations of their recommendations. National leaders also need to ask advisors to structure reflective reports in the format of brief narratives (Sanne, 2008) that help them easily grasp the complexity of an argument. The objective of institutionalizing reflective reports into decision making under uncertainty is to ensure that leaders are not overwhelmed by the increasing number of information they are bombarded with. The simple structure of reflective reports also helps leaders understand and remember the key points presented to them before deciding (Wright & Goodwin, 2009).

4. METHOD

The objective of reflective reports is to help decision makers and their ad hoc committee to make the best possible decisions under significant time, information, and resource constraints (Parliament, 2020). The main assumptions of adopting such a methodology are that leaders i) have selected the most thoughtful communicators (Stewart et al., 2020) in the country to join this crisis response task force and that these advisors ii) do not hesitate to challenge their own assumptions and swiftly change course when conflicting information emerges. The expectation is that leaders adopting this method can optimize decision-making processes and reduce the risks of making decisions that will act against the public interest (Scicluna & Auer, 2019).

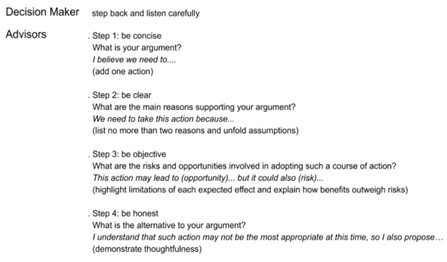

Figure: Structure of 4-Step Reflective Report

The length of each report varies in terms of the number of advisors and time constraints to reach a decision. The duration of the entire deliberative process should be kept to a minimum. Keeping it short ensures that the decision maker is not overwhelmed and can consider each argument before making a decision. Brevity in this deliberative process is also encouraged because it is expected that these meetings will occur daily and sometimes more than once a day.

5. LIMITATIONS

Reflective reports in the context of decision making under uncertainty present limitations. The first one has to do with the ability of advisors to translate complexity into compelling narratives without missing key facts. Advisors may also excessively simplify their interpretation of reality for the sake of clarity (Feitsma, 2018). The second limitation has to do with gatekeeping (Dargent, 2015, p. 112). National leaders must ensure that an ad hoc committee is not only composed of well-known experts in each field, but it also gives opportunity for thoughtful communicators to share heterodox ways of thinking (Land et al., 2010; Ogbunu, 2020) and suggest unexpected courses of action (Filgueiras, 2019, p. 9). The third limitation has to do with the cognitive ability of decision makers. Leaders need to be aware of their biases and blind spots (Edwards et al., 2016). Self-awareness allows decision makers to prioritize what it is in the interest of the public good rather than their own or their group. The last limitation assumes that each advisor's recommendation enjoys the same weight in the final decision. However, it is expected that leaders would be more inclined to consider recommendations that corroborate their preexisting values and beliefs (Buckley, 2017, p. 4) or be more acquiescent to advisors that had some leverage on their past decisions.

6. CONCLUSION

This article argues that national leaders can reduce the risks of the decisions they make under uncertain scenarios. This happens when leaders gather and actively listen to an ad hoc committee made up of thoughtful communicators. These advisors tap into compelling narratives to share opinions concisely and objectively. Leaders, however, face many constraints to respond to unfolding crises in a timely manner. These constraints lead them to invariably resort to mental shortcuts before reaching a decision. Intuition, however, can lead to undesirable effects. Thus, this paper proposes the addition of a straightforward reflective report into deliberative processes to help decision makers and advisors alike interpret and communicate perceived and shifting realities on the go.

Reflective report provides a simple structure for advisors to organize and challenge their own thoughts and opinions. It also helps national leaders grasp and process information. In the Brazilian context, it is expected that the president works closely with an array of experts from different fields and fairly listens to them before making decisions. This expectation, however, has become more of a wishful thinking recently. This is because there has been evidence that a recently organized ad hoc committee has not been given the necessary consideration by the president (de São Paulo, 2020). The national leader has also shown not being able to convince the society that his proposed policies are in the interest of the public good rather than his own political agenda (Raco & Savini, 2019, p. 225).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector. The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

REVIEW COMMENTS

R1: Phil Lord

This is a good paper that provides an assessment of how elected policy leaders can best respond to the pandemic. The author’s argument is properly supported by the literature, though the paper would benefit from a more thorough explanation of the relevant theoretical frameworks. It at times becomes unclear where the author draws from the literature and where they are extending or applying a theoretical framework in novel ways. The language level is generally appropriate, but there is a tendency to over-assert and generalise, especially in the earlier portion of the paper. Some additional proofreading would be appropriate. As much of the paper is dedicated to the situation in Brazil, the paper would benefit from a more detailed application of its recommendations to Brazil and an assessment of the unique challenges to doing so (given the political context described in the paper).

Thank you for the opportunity to review this paper. I look forward to reading the revised version in published form.

R2: Gerit Pfuhl

- I recommend to establish early on that a pandemic is a time where decisions have to be made on little evidence. It is thus necessary to be transparent about uncertainty (papers addressing that (there are many more): e.g.

Moon, M. J. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 with Agility, Transparency, and Participation: Wicked Policy Problems and New Governance Challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 651-656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13214;

van der Bles, A. M., van der Linden, S., Freeman, A. L. J., & Spiegelhalter, D. J. (2020). The effects of communicating uncertainty on public trust in facts and numbers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7672. doi:10.1073/pnas.1913678117

Porzsolt, F., Pfuhl, G., Kaplan, R. M., & Eisemann, M. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic lessons: uncritical communication of test results can induce more harm than benefit and raises questions on standardized quality criteria for communication and liability. Health Psychol Behav Med, 9(1), 818-829. doi:10.1080/21642850.2021.1979407

- After that, the case of Brasil vs New Zealand could be made. I.e. review the different options countries have chosen (e.g. China, New Zealand, UK, Sweden vs Brasil = Wuhan lockdown, border closing, full transparency about known unknowns and unknown unknowns, etc).

That can be linked to what is and is not feasible in Brasil (compared to China, Sweden, New Zealand). This allows the reader to see what are structural causes (poverty = die from COVID rather hunger) and what are political causes (belief in virus being harmless). However, this section can be short as it is not required for your “reflective report” crisis management

- Indeed, more literature is warranted on crisis management (this is not my field of research, suggested readings:

Arnot, M., Brandl, E., Campbell, O. L. K., Chen, Y., Du, J., Dyble, M., . . . Zhang, H. (2020). How evolutionary behavioural sciences can help us understand behaviour in a pandemic. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 2020(1), 264-278. doi:10.1093/emph/eoaa038

Weber, E. U. (2006). Experience-Based and Description-Based Perceptions of Long-Term Risk: Why Global Warming does not Scare us (Yet). Climatic Change, 77(1), 103-120. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9060-3

Marais K., Dulac N., Leveson N. (2004). Beyond normal accidents and high reliability organizations: The need for an alternative approach to safety in complex systems, ESD Symposium 2004.

- Then the pro’s and con’s of the reflective report’, situated in alternative advice-systems (“classical” advisory boards, going by intuition, etc). Indeed many countries have temporarily “suspended” democratic features to cope with the pandemic (emergency laws / rules).

“The expectation is that leaders adopting this method can optimize decision-making processes and reduce the risks of making decisions that will act against the public interest (Scicluna & Auer 2019).”

- Could you please expand this argument, i.e. how does a reflective report lead to optimization, and why is it for the public interest? Is that not based on the advisors and the intimidation of the leader? I.e. can you speak up truly freely as advisor?

- It is also not clear in the method section how advisors are chosen (by competency I hope), and in which order they present their reflective report, i.e. is there a dialectic interaction between advisors, or is each advisor presenting their report and the decision is based on how many advisors opt for solution / action X? If arguments should matter, shouldn’t advisors have a chance to counterargue an argument a previous advisor has said? Would that not be more objective? Even if step 4 (alternative to your argument) is fully applied, how does one avoid recency effects (one only remembers the last part)?

Author’s Response

R1: I would like to thank Prof. Lord for his time reviewing and sharing valuable comments to this project. Most of the recommendations were incorporated into this manuscript. The remaining ones will be incorporated in the next rounds of the project.

R2: I would like to thank Prof. Pfuhl for reading and sharing valuable comments to strengthen the first round of this project. Unfortunately, I have not been able to incorporate all recommendations in this manuscript, but I will certainly do so once data is collected for in-depth analysis of the main argument.