1. INTRODUCTION

Depressive symptoms are common among students (Knapstad et al., 2018), with many individuals remaining untreated (Kazdin, 2017). The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic situation increases feelings of isolation and worry (Mækelæ et al., 2020). The increase in mental problems during a pandemic unveils the already limited capacity of therapists and clinics. Furthermore, geographical restrictions and factors related to the individuals in need of help (e.g., fear of stigmatisation, restricted mobility because of physical conditions or apathy can delay treatment (Kohn et al., 2004; Mohr et al., 2010).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is currently the most evidence-based psychotherapy for depression (Driessen et al., 2016). More recently, mindfulness-based therapy (Khoury et al., 2013), and metacognitive therapy (Wells & Papageorgiou, 2004), have proven to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression (Churchill et al., 2013, Normann et al., 2014, Strauss et al., 2014); and also for metacognitive training for depression there are promising findings regarding its efficacy (Jelinek et al., 2105, Jelinek et al., 2016). Notably, e-health technology-based interventions such as self-help apps can be complementary to face-to-face interventions, as well as they can bridge the gap due to waiting time and follow-up of treatment.

Several of the existing self-help apps are independent of geographic constraints and time (Twomey & O’Reilly, 2017), they offer anonymity (Young, 2005) and low delivery costs. Among Germans (sample from the general population) the attitude towards such interventions is positive, i.e. in a survey (N = 2411), more than one-fourth (26.3%) of Germans could imagine seeking information and help online in case of a mental disorder or emotional distress. Interestingly, willingness to use therapeutic online counselling is higher in individuals who frequently use the internet and related devices (Eichenberg et al., 2013). The demand for online counselling will likely increase with growing digitalization in the future. Therefore, technology-based support and treatments of psychological disorders, also known as e-mental health, have the potential to support/decrease the treatment gap in the mental health system.

Several psychological online interventions (POIs) for the treatment of depressive symptoms have been developed and evaluated in the last decade, yielding small to medium effects with unguided POIs showing small effects in a meta-analysis by Karyotaki et al. (Karyotaki et al., 2107). Furthermore, an effect in favour of smartphone-based interventions over control conditions with no smartphone app has been found (Firth et al., 2017).

Preliminary evidence indicates that smartphone-based interventions could complement face-to-face therapies (Ly et al., 2015). The combination of face-to-face and technology-based interventions is called “blended therapy”. One of the challenges in technology-based interventions is to sustain treatment effects after treatment has ended, and preliminary evidence from obsessive-compulsive disorder research suggests that “booster programs” (i.e., additional therapy sessions after treatment completion) could help to preserve treatment effects (Andersson et al., 2014). Smartphone applications could help to sustain treatment effects by sending frequent reminders via push notifications.

Another challenge is uptake and usage, i.e., participants may not use the provided e-health tool. Price et al. (Price et al., 2012) found that 48% did not access a web-based mental health intervention. Similarly, among adolescents the attrition rate for a smartphone based mental health app was 35% (Egilsson et al., 2021).

In this study we aimed to monitor the change of symptoms of depression and anxiety throughout the reduced social life during the coronavirus pandemic using a self-help app to measure the efficacy and feasibility (attrition, duration, participant evaluation) of two different apps for mental self-help among students. We hypothesised that using the smartphone application would result in decreased depressive symptoms, increased self-esteem, and a higher quality of life. We also measured reasons for not using or continuing to use the self-help apps. Here we focus on the uptake and usage of e-mental health.

2. Methods

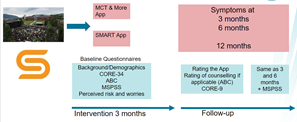

Study participants were university students at UiT, The Arctic University of Norway. Students were recruited over a two months period to participate in the study starting in January 2021 with the first follow-up 3 months after recruitment. Recruitment was through two means: 1) through the Student Welfare Services and 2) general recruitment through advertisement flyers (in paper and screens at campus) and social media. This was in order to include two student populations of interest – those accessing counselling services through the Student Welfare Service for whom the app was an add on to counselling and the general student population with a self-perceived need for help. Participants were asked to complete an online survey including questions on demographic factors, current mental health status, perceived social support and anticipated benefits of treatment. They were also asked about perceived risk and worry related to the pandemic situation. After completing the survey, the participants were randomly assigned a link to download one of two apps designed to improve mental health symptoms: MCT & More app or the SMART app (see figure 1). The apps were available in Norwegian and English language. Participants were instructed to use the apps everyday throughout the study period. Follow up questionnaires were sent via email to study participants at 3, 6 and 12 months. At the time of writing the 12-month data collection has not yet taken place.

Figure 1: Mental self-help apps provided to study participants; Top row: Screenshot of how the MCT & More app (recently renamed as COGITO) was presented in the Google Play Store, English version shown (download link:(https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.uke.cogitoapp&hl=en&gl=US "https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.uke.cogitoapp&hl=en&gl=US")). Bottom row: screenshot of the SMART app (SMART stands for Stress mastering activities for robustness training), Norwegian version shown ( download link).

2.1 Intervention

The MCT & More App provides daily exercises for one’s mood across categories of cognitive strategies, mindfulness-based exercise, social-competence skills and activating exercises. The participant's use is monitored and provides feedback with recognition for “achievements” using medals to encourage regular use. The app is meant to be used daily as part of a regular routine. Therefore, the explanations to the exercises are designed to be easy to read and described in less than 150 words taking approximately two minutes to read. A countdown is activated with the exercise to encourage users to take this time to read the exercise properly. The MCT & More App has been evaluated in Germany in two randomised controlled trials among 90 and 400 participants who felt a subjective need for help with depressive symptoms (Lüdtke et al., 2018; Bruhns et al., 2021). The majority of participants rated the app positively. Among those who used the app regularly (61% of the intervention group, Lüdtke et al., 2018), there was a small but significant decrease in depression symptoms compared to the control group. The content of the app was translated to Norwegian by our research team. The app has recently been renamed “Cogito”.

The SMART App uses a range of cognitive behavioural therapy tools with a focus on managing stress. SMART is an app translated from English to Norwegian and developed by the Regional Centre - Violence, Trauma and Suicide Prevention - Region East (RVTS East) in Norway, that provides advice and exercises aimed at helping users to calm down, sleep better, deal with irritability, stop negative thinking and deal with life challenges. It is designed for use from the age of 14 onwards. The app was originally developed by the Phoenix National Centre for Excellence in Posttraumatic Mental Health, for the Australian defence.

The two apps were chosen based on availability in both Norwegian and English language, they were free to download to both Android and iOS operating systems and the participants do not share any data from the apps. The MCT & More app is designed to use as an add-on treatment in depression but also as a stand-alone tool (Bruhns et al., 2021). Furthermore, the app is based on therapeutic techniques (group metacognitive training (MCT)) shown effective in reducing anxiety, depression and dysfunctional metacognitions (Normann & Morina, 2018, Normann et al., 2014). The SMART app is in clinical use in Norway; however, it has not been validated in a Norwegian population. It has been evaluated among Australian defense members who evaluated the app’s functionality positive, but with potential for improvements (Shakespeare-Finch et al., 2020).

The provision of these apps is additional to any treatment or support that students are receiving already or would usually be offered by the Student Welfare Service and will not be seen as a replacement. Therefore, this study will not affect the usual standard of care and support offered to students. Usage of the apps are seen as adjuncts to normal standard of care in those receiving treatment or in situations where students would not receive treatment (due to either a long waiting time / low threshold of symptoms / not seeking help). The participants were recommended to use the app for 3 months, or longer if preferable. We did not have access to any information from the app’s usage by the participants, only (see below) self-ratings and reports in our surveys.

2.2 The survey

In the survey part we collected demographic information at enrolment (age, gender, study year, living condition (student dormitory, shared flat, own flat), civil status (single, in a relationship, married and cohabiting, in a relationship, married but living apart), previous mental health issues).

Figure 2: Recruitment was either from the student population or from the Student Welfare organisation (yellow S). Participants were randomly assigned to either receive a link to the MCT & More App or the SMART app and either for Android smartphones or iPhones.

We also asked on a 11-point scale about COVID-19 worries and financial worries (0 = no worries at all, 10 = highly worried). All questions in the survey were available in both Norwegian and English language for the participants to choose.

At enrolment, 3-, 6- and 12-months follow-up we collected self-report through the electronic questionnaires regarding attitudes and expectations about treatment if they receive this using the 10-item anticipated benefits of care (ABC) (Warden et al., 2010). They were asked to report psychological distress and outcome of therapies if received using the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) excluding the six items on suicidality (Connell et al., 2007). We used a general measure of family and peer provided support with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988). Finally, they were asked about the type and amount of counselling received last week / current week. Figure 2 illustrates the study design.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, North (2020/155666) and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (Ref 850249). All participants consented to participate in the study.

3. Preliminary results on app uptake and usage

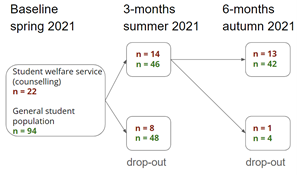

The number of participants taking part in the study at baseline, 3 months and 6 month follow up is shown in Figure 3. In total 116 participants were recruited at baseline - as of 94 participants reported that they did not receive counselling, and 22 participants that they received counselling for mental health problems. The majority of participants were women, between 20-24 years old and most were at the Bachelor or Master level (6 took only single courses, and 12 studied a topic that leads to approbation. Half of them were single, the other half were in a relationship, 20% lived alone. 15% stated a previous depression and 8% a current depression. 9% stated previous anxiety and 12% current anxiety.

At 3 months the retention in the study was similar in the general student population sample (n=46, 49%) and in the sample that received counselling (n=14, 64%), χ2 = 1.5428, p = .214. Average attrition rate was 48%. Attrition rate was higher among those without mental health problems, i.e., of those who reported depression at baseline 22.2% dropped out (2 of 9) and for anxiety at baseline 28.6% (2 of 9) dropped out from the study at 3 months follow-up.

Figure 3: Recruitment and attrition in absolute numbers.

Reported usage of the app at 3 months follow-up was low too. Among the 60 participants who completed the 3-month questionnaire 20 participants (33%) had not downloaded the app, 23 (38%) only used the app in the beginning of the period and only 8 used it at least once per week. Reported use of the app at 3 months was similar among those receiving counselling (n = 10, 71%) and the general student population group (n = 30, 65%), χ2 = .1863, p = .666. If excluding those that indicated only using the app in the beginning, app usage was very low among those receiving counselling (n = 5, 36%) and among those from the general student population (n = 12, 26%), χ2 = .49, p = 484.

Among the 49 indicating not using the app (much) or downloading the app where; 12 (24%) reported not understanding the app, 10 (20%) reported technical problems with the app, 3 (6%) reported that their phone got stolen or lost, 13 (26%) reported that the app was too much effort, and 11 (22%) stated that they felt better and had no need for the app.

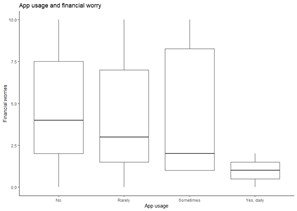

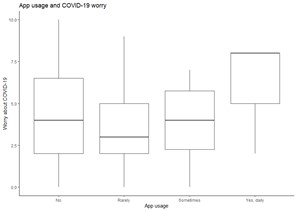

Finally, we looked at whether demographic variables, depression or anxiety at baseline did relate to app usage. There was no clear pattern. However, the more a participant indicated to be worried about COVID-19, but not about financial worries, the more likely it was that they would use the app regularly (figure 4).

4. Discussion

This study was a pilot study aiming to investigate the feasibility of using e-health tools in the form of apps to improve students’ well-being and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic with restrictions of social interaction. A key issue identified was that uptake and use of the apps was low, in addition to 48% attrition rate at the 3-months follow-up. This substantially limited the ability of the study to evaluate the effectiveness of using the apps on mental health in a group of students. Uptake and study retention was not affected by the recruitment method. App usage was further not driven by living conditions (e.g., alone or with others) but by COVID-19 worries. This may in part reflect a higher perceived need and therefore valued the use of the app. This may have motivated more participants in this group to engage with apps initially and continue to take part in the study. Indeed, Price et al. also reported that among those not using their web-based mental health intervention 41% felt it was not relevant. Future recruitment should be more tailored to those in need and ideally provide a personalised app.

We found that there were more dropouts among the students that reported that they had no depression and/or anxiety. The high attrition rate could be related to both that some participants felt they did not need the app, as for other participants reporting depression, anxiety and mental health challenges could limit their capacity to download and learn how to use the app.

Figure 4 : Boxplots of app usage (four categories). Top row: COVID-19 worry, bottom, row: financial worries, rating was on a 10-point scale from 0 = no worries to 10 = highly worried

Even among those who continued to take part in the study at 3-months follow-up there was a relatively high proportion of participants who had not actually downloaded the apps. Given the aim of the study it was a surprising finding that participants would take part in a study about use of apps to improve their mental health, and completed the questionnaires despite the fact that they did not download the app. Half of those who did not use the app stated that they either did not understand it or that it was too much effort. This appears especially for the SMART app which was originally developed for use among Australian veterans (helping with post-traumatic disorder). However, also the MCT & More app had modules on gambling and psychosis which might have confused participants whether the app is tailored to their needs.

For future research we would recommend providing more detailed guidance on the practicalities of downloading the app. In addition, how to use the apps could have been introduced using in-person online support, screenshots of what participants should do at each stage of the process and followed-up with in-person online support. Since none of the apps was specifically tailored to the COVID-19 pandemic but rather used general cognitive behavioural therapy tools, adaptations even if only on the outside might increase uptake. A more personal approach to recruitment with in-person technical support on hand to help with the download process could also improve initial engagement. Limited use of the apps may be related to COVID-19 pandemic factors which have resulted in higher levels of screen time generally for work and socialising activities. To increase this even more through daily use of an app, may limit the desire to use another digital technology to help alleviate mental health symptoms (e.g., Meyer et al., 2020, Mækelæ et al., 2021, Wong et al., 2021). Furthermore, Baumel et al. (Baumel et al., 2019) report only few that continuously and over a longer period engage with smartphone mental health apps. This is though not restricted to e-mental apps (e.g., Bradway et al., 2018) and may reflect general challenges of e-health.

In this study students were the targeted group as they are considered a vulnerable group, and even more during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Studies have showed that students have experienced mental health problems related to depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also a lack of awareness of mental health apps and uncertainty how to use apps (Drissi et al., 2020, Marques et al., 2021). However, we believe that our findings on the low attrition and limitations of using apps are relevant also to other targeted adult groups.

In developing and/or implementing use of apps to people experiencing mental health challenges and with limited access to treatment it is important to involve the target group in development of apps and implementation processes to make it relevant, user friendly and with in-person support.

In conclusion an important limitation to using self-help apps to improve mental health identified in this study was in motivating initial engagement to download and use the apps. Before the utility of apps for improving mental health can be evaluated the barriers to engagement need to be understood and adequately addressed in the design of future research studies on using and implementing apps for improving mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to the support from the student welfare organisation who generously assisted in recruiting participants.

REVIEW COMMENTS

R1: Muneo Kaigo

The paper addresses some quite interesting aspects of self-help apps to enhance mental health issues related to COVID-19. Although the work is in the preliminary stages and is conducted at a difficult time and complicated target to measure correctly due to the continuing problematic situation created by the global pandemic, the study directs future studies on how to create a more comprehensive architecture to conduct research in this topic. The limitations are insightful and the challenges that this study faced are convincing. I believe that this paper contributes to the literature related this issue and suggest publication

R2: Concetta Papapicco

The paper “Mental health self-help apps for coping with COVID-19” address an interesting topic starting from the increase in mental problems during the pandemic period and, consequently, the spread of psychotherapeutic applications. The authors measured the efficacy and feasibility (attrition, duration, participant evaluation) of the two apps (i.e. “MCT & More App” and “SMART”), assuming that using the smartphone application will result in decreased depressive symptoms, increased self-esteem, and a higher quality of life. The results show how Depression, anxiety or demographic variables did not explain app usage, however, worry about COVID-19 did. The study is very interesting especially for the practical impact of the results. The paper is well written. The methodology is well described and the description of the sample is well detailed. However, minor revisions are required, as specified in the previous table.

Author’s Response

Reply to R1: Thank you very much for the kind words. We have added more justification for use of the two apps and why we focused on students. We would also like to clarify that depressive symptoms fluctuate over time and can be caused by a range of factors such as daily life stress, negative events, losses, somatic illness, etc. It is common and quite normal to feel tired, sad, having a lack of energy, trouble sleeping, feeling lack of enjoyment, negative view of self or future. However, experiencing these symptoms does not mean that one meets the criteria for a clinical diagnosis, or that it is a depression that is causing these symptoms.

Reply to R2: We thank you very much for your suggestions and agree that app-usage should be investigated across cultures. Previous studies (pre-pandemic) found a higher app uptake (Bruhns et al., 2021, Lüdtke et al., 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic and its worsening of student mental-health might have affected app uptake