Like the literary scholar that I am, I want to begin my remarks with a sort of epigramme:

“Unlike the DeGroot model, which always converges in a consensus when G is connected (i.e., z ∗ i = z ∗ j for all i, j) , innate opinions allow for a richer set of equilibrium opinions. In particular, z ∗ will typically contain opinions ranging continuously between –1 and 1.”

This quote comes from an article by Chitra and Musco about the dynamics of filter bubbles, which I sometimes ask my Masters students to read and discuss. I do this in part because of the usefulness of Chitra and Musco’s overall argument, but also so that the students can experience something that I think is very important to remember in the context of the topic of multilingualism and the assessment and impact of scholarship: that different scholarly communities in essence always use different languages to maximise the precision of their arguments. This does not necessarily mean that they do it well, however. Here is another quote I would like to share with you:

“Data pretreatment module is outside from online component and it is done to preprocess stream data from the original data which is produced by the previous component in the form of data stream.”

This gem was uncovered for me by a young scholar of English who happened to be working with me on a project about how scholars in different communities talk about data. Needless to say, she spent her days with me in a state of bewilderment at her sudden alienation from her mother tongue.

My poor suffering researcher’s nerves notwithstanding, this quote and the path by which I was introduced to it, bring forward a second important element to consider in the context of our meeting today, which is not about multilingualism and the evaluation of all scholarship, but of that in the humanities and social sciences in particular. Not only are we, as is true of all disciplines, in need of specialised linguistic tools to make and express our arguments with precision, we are also, far more uniquely, as concerned with questions of the form of that argument as we are of the function. Some years ago, I did a series of interviews with humanistic scholars in my institution, trying to uncover some of the pillars of their largely tacit methodologies. The need to polish the mode of expression in their published work was a constant theme: one of my interviewees said, “As well as instructing, you should delight,” while others spoke of wanting their writing to be “stylish,” “the reader’s part of the scholarly journey,” “challenging…witty,” “lively” or indeed even written with “a certain ‘je ne sais quoi” or indeed addition of “pixie dust.”

The entanglements of excellent humanistic scholarship with precision of expression does not begin and end with the writing of the prose, however. In fact, the place of language in the shaping of scholarship begins, at the very beginning of the scholarly journey, with the availability and accessibility of source data. It is important not just to consider the real or apparent efficiencies of the wider research ecosystem that could be realised should we all think and write in and about the same language, but also the opportunity costs of such a worldview**. Limiting the languages of scholarship also means limiting the research questions that can be asked, and the instruments that are developed to support analysis.** As one post-doctoral researcher in science and technology studies interviewed within the OPERAS-P project expressed it:

“I always feel whenever I work with Czech data, I somehow have to justify why I am working with the Czech data and why that is interesting. I always feel like if you're an American or you're English, working with English or American data, you don't have to explain why that topic is interesting.”

It is not only history, it seems, that is written by the victors.

But who are the real losers? I would say that while of course the cultural fields, so dependent on the finesse of particular natural languages, and the scholars that work in them may certainly feel most keenly the impoverishment of monolingual scholarship, it is ultimately the culture, the public sphere and the communities that have the most to lose. What happens when culture is no longer open to interrogation? When discourses about cultural practices become estranged from those practices? Then that very loss in finesse that is felt by the researchers is passed on to the students they train, the media they inform, the policies they influence. Even if we assume all scholars can work through a single vehicular language, in baking this assumption into a rule, we make dangerous, narrowing, conclusions about the wider audiences of scholarship, and risk closing the door on much of the impact we might now have come to expect of scholarship.

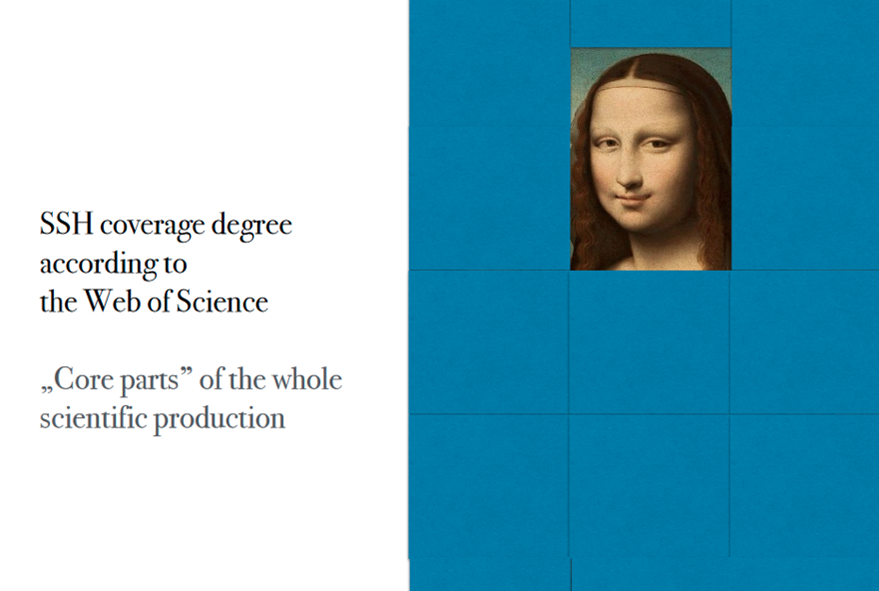

These concerns about the narrowing of scholarly horizons bring me to the question of infrastructure, something I, as President of the Board of Directors of a European Research infrastructure, DARIAH EU, happen to think a lot about. I was very excited to notice that Emanuel Kulcycki would be on one of the panels today, as it gave me an excellent excuse to reuse his wonderful visual expression of the state of our infrastructure for measuring the impact of research in the humanities:

If we are to maximise the impact of the SSH – and it seems beyond question that so much valuable scholarship must be fully integrated into our value chains for research – then we will need better infrastructures to enable this scholarship to be findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable, but also assessable, and this infrastructure should be optimised to do this across languages. By aligning not at the roots of scholarly production, but at the branches of data aggregation about that scholarship federation, we can preserve the strengths of linguistic precision within humanistic scholarship, while also gaining far greater visibility for scholarship created within any language or cultural system. We could also provide scholars with the tools to explore that scholarship in all its richness, though of course the resource they may need most to extract the value from a system like this is actually time, something no digital infrastructure can provide.

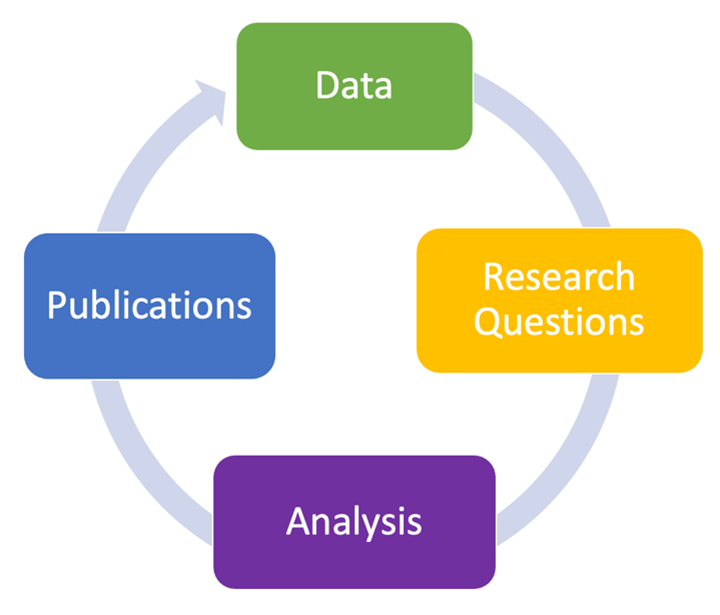

To create this infrastructure, we do not have to reinvent the wheel – in fact, we have many of the required elements already built. Specialised data are already held in the many national museums, archives and libraries, while research questions can be fostered in the research performing institutions. My own infrastructure DARIAH works to make these data and methods as well as the analytic tools needed for research accessible, while our sister organisation OPERAS seeks to ensure open and rich publishing cultures. At the level of integration, the OpenAire Research Graph is a powerful tool for providing the overview required for assessment exercises of all sorts. The opportunities to bring these elements together to reinvent a richer research culture are many.

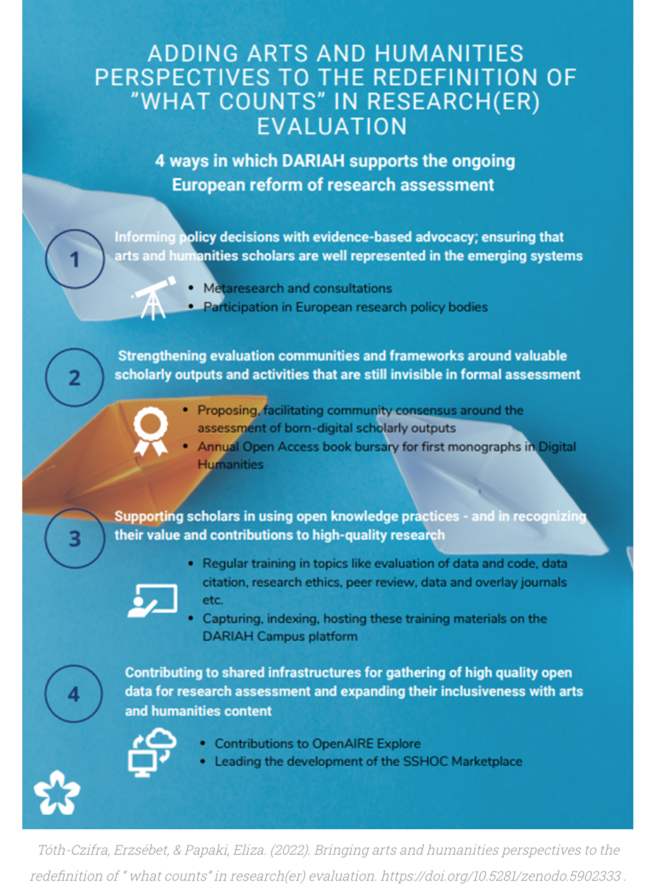

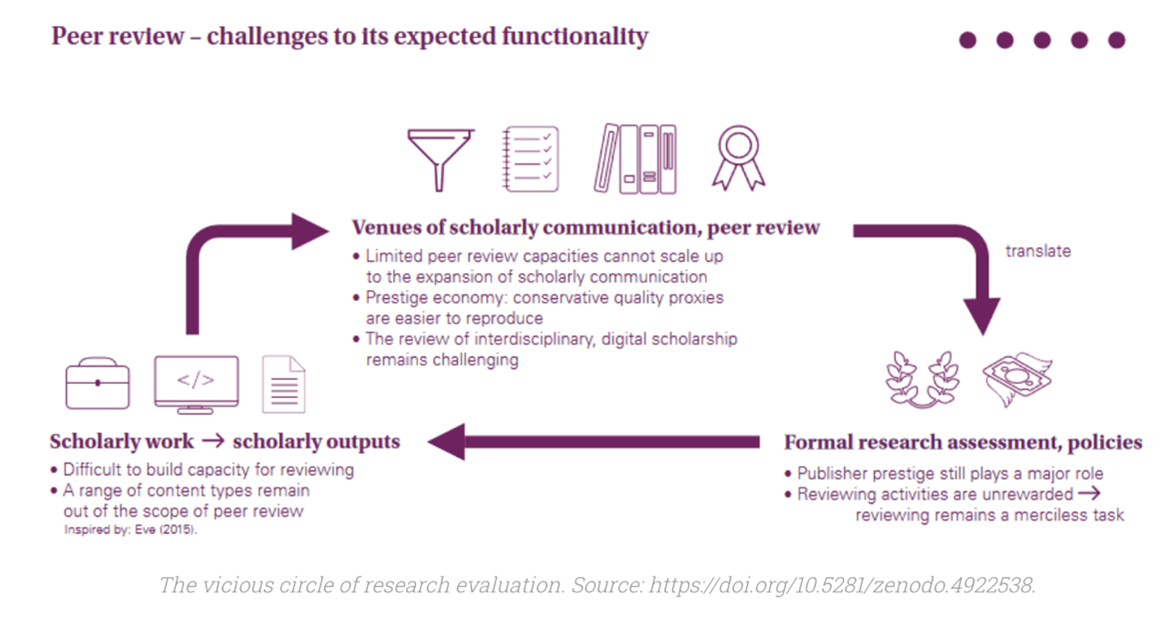

In DARIAH, we are very committed to the vision of a research landscape in which the traditions of humanistic scholarship across disciplines and languages can flourish, with work able to reach its full potential, and be assessed and appreciated on its merits. For this reason, we’ve recently been taking part in the Commission’s stakeholder exercise toward reforming research assessment, building on our experiences of informing policy, strengthening evaluation frameworks, supporting open knowledge practices and, of course, building infrastructure. In particular, we are interested in the ‘vicious circle’ of peer review, which seems to trap us in a system of perverse incentives that are currently not satisfying scholars, publishers or assessors of research.

In a complex and challenging world, why would we want to take a toolset like the one on the left and reduce it to something orderly, yes, but far less useful like we see on the right?

In this, I believe the arts and humanities can lead, if only because our objects of study make it very clear that the more we try to organise and simplify the languages of scholarship, the more we diminish the enterprise. These languages of scholarship are always already inflected by the cultures that creates them, and to force an artificial unity on this diversity will never, ever add to its richness. If we build infrastructure starting from this premise, we may well find that we can maintain a rich and vibrant impact, even where assessment may incentivise black and white.