Introduction

Do we respond similarly to news of petty crimes, police brutality, insurrection on the US Capitol, discriminatory social policies, or terrorist attacks? Some of these events betray basic values and principles, such as people's inherent worth and equality, respect for human rights, the importance of civil society, and the rule of law. This is the case because humans are a judgmental bunch. Cross-culturally, since the dawn of humanity, people judge some behaviors are right or wrong and deserving rewards or punishments. Perceptions of morality are increasingly generalized as people inhabit larger and more unfamiliar social networks and interact with anonymous persons (Jackson et al., 2024). Moreover, and contrary to what many people believe, morality (kindness, civility, honesty, and basic human decency) is not declining. It is just the opposite, as shown by a study spanning 60 nations worldwide (Mastroianni & Gilbert, 2023). On average, we treat each other far better than our forebears.

Converging lines of evidence–from game theory, biology, anthropology, psychology, and economics–suggest that morality is a collection of evolved adaptations for promoting group living and cooperation (Curry et al., 2019; Enke, 2019). As an ultrasocial species, humans highly value teamwork and cooperation, and our collective orientation benefits us individually by helping gain coalition partners, mates, and friends. The constellation of thoughts and feelings that constitute a sense of morality has evolved to enable individuals to uphold cooperative social relations that maximize their biological benefits (Krebs, 2008). However, while the capacity for morality is universal, there is tremendous variability in which behaviors people think are immoral. Despite substantial individual and cultural variation, nearly all manifestations of morality involve, are based on, influence, and govern our relations with other people (Rai & Fiske, 2011). Furthermore, morality has evolved as a natural extension of our coalitional psychology (Tooby, 2017). As a result, it is strategically tuned to specific aspects of group dynamics. This cultural-evolutionary account explains why morality can lead to dogmatism, intolerance, and violence.

What people believe to be of moral value has a huge impact on society, especially by motivating participation in collective action (cooperative effort towards group status improvement) and inspiring the courage to oppose injustices despite personal cost. Many positive societal changes, such as the struggle to obtain the right to vote for women in the United States in the 1920s, the civil rights movement in the 1950s, and the legalization of abortion in the 1970s around many countries, were the result of people holding strong moral convictions and their tireless engagement in a collective effort.

At the same time, moral convictions can facilitate hostile, inflexible, and at times violent actions, ranging from the cancellation of a book launch 1 to inter-ethnic riots that leave scores of people dead. For better or for worse, moral convictions trigger more ardent reactions than other attitudes and beliefs. The extent to which a person considers a given topic (e.g., mining, the use of glyphosate, illegal immigration or the commercial use of body parts to take a few examples) to be within the scope of moral beliefs that are perceived as transcending the boundaries of persons, cultures, and contexts has wide-ranging and a variety of predicted negative interpersonal outcomes. These include dogmatism, intolerance of those who do not share the same views, unwillingness to compromise or accept procedural solutions to conflicts with little space for economic gain, and a host of other potentially harmful consequences.

This dark side of morality is the focus of this essay. Given that strong moral convictions are likely to be associated with acceptance of any means to achieve preferred goals (Skitka, 2010), a better understanding of whyattitudes rooted in morality can promote disruptive forms of social engagement constitutes an important endeavor for interdisciplinary research with consequences to public policy.

In this article, I adopt a naturalistic perspective 2, integrating empirical evidence and theories from multiple disciplines. Social phenomena like morality can be more comprehensively and accurately understood if their explanations maintain consistency and coherence across different levels of analysis. A vertical integration of knowledge across the biological sciences and the social sciences requires an effort to make them coherent and consistent (Cosmides, Tooby & Barkow, 1992). A biological perspective can inform social systems and provide a comprehensive understanding of social phenomena. Observations, knowledge, and concepts of higher and lower levels of analysis can mutually inform and calibrate those of other levels. Moreover, because of the emergent properties of complex organizations, it is unlikely that an understanding of higher-level psychological processes can be satisfactorily derived from neurophysiology alone (Berntson et al., 2012). Nor, for that matter, by a restricted analysis of any single level of organization or function, whether it be sociological, psychological, or neurobiological. Thus, these differing perspectives need to be integrated.

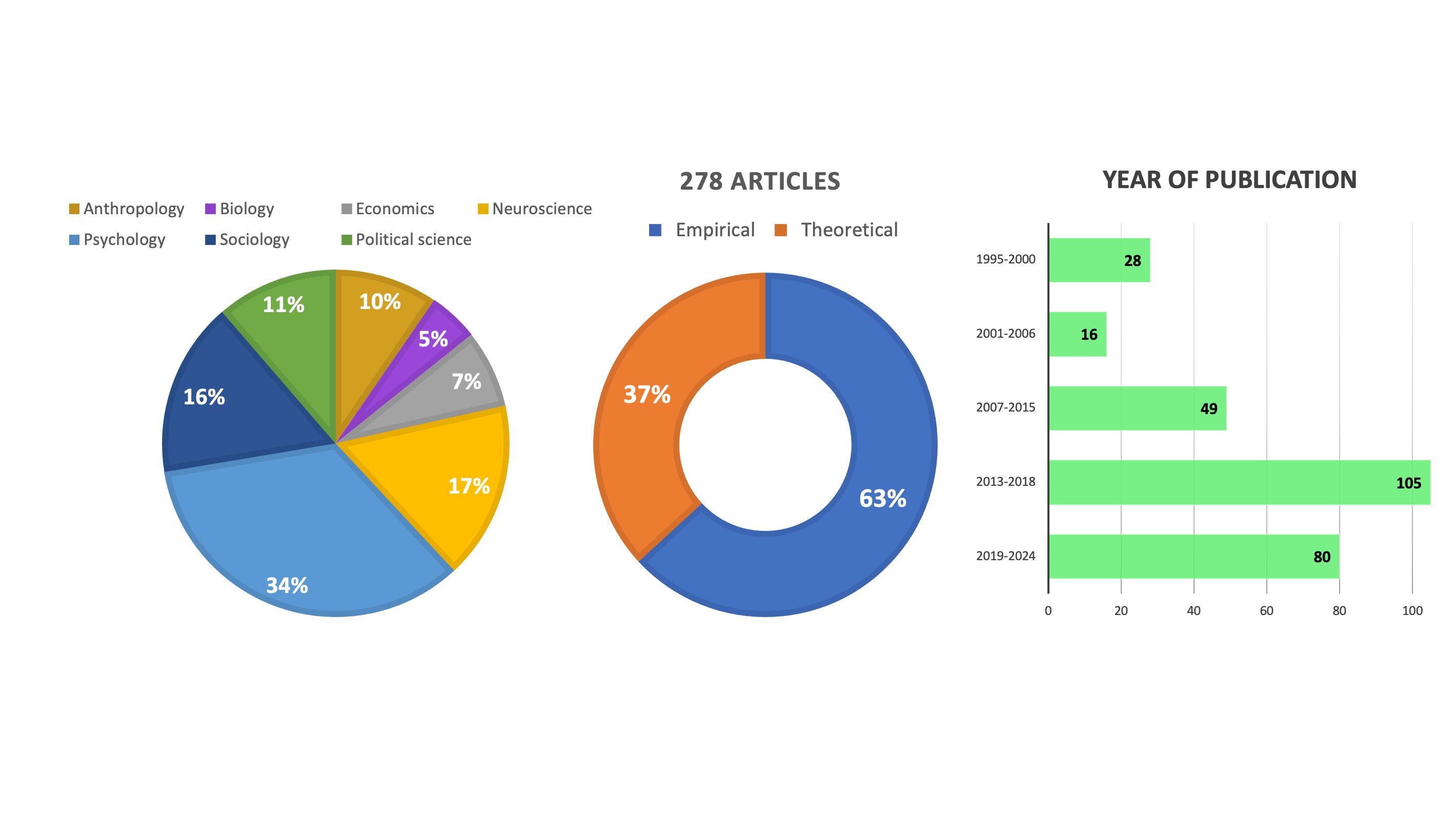

This article develops an integrative analysis of the empirical and theoretical literature based on a selection of articles from the social sciences and the biological sciences (Figure 1), to explain why and how the moralization process increases the strength of beliefs and attitudes - in certainty and importance - which, in turn, motivates social commitment and induces dogmatism and attitudinal extremism at the individual level, regardless of ideological or political affiliation.

The article is organized into eleven sections. Following this general introduction, the second section explains why studying moral conviction matters. The third section presents a functionalist perspective on morality as it is currently described in evolutionary anthropology and psychology (developmental, cognitive, and social), followed by a section on the social domain theory of morality. The fifth section focuses on virtuous violence. The interwoven nature of morality and group dynamics, which stems from the selective pressures inherent in the evolution of our species is the subject of the sixth section. The cognitive architecture of moral convictions is outlined in the seventh section, followed by a section describing the moralization process and its neural mechanisms. Mental rigidity, a sense of superiority, and high subjective confidence are frequently associated with moral convictions. This class of phenomena, grouped under the umbrella term of metacognition, is the subject of the ninth. A final section before a general conclusion briefly addresses strategies to counter moralization. A glossary of the terms and key concepts used in the paper (e.g. coalition, reward system, social influence, valuation) is provided before the list of references.

Overall, the understanding that emerges from integrating social sciences and biological science knowledge, demonstrates that moralization strongly increases the strength of attitudes –their certainty and importance– which in turn motivate political commitment, dogmatism, and ideological extremism, independent of the political sophistication of the actors and across the political spectrum. Moral conviction is the catalyst that turns beliefs into action, for better and for worse.

Why studying moral conviction matters

Moral convictions can inspire change and positive collective action but can also prompt dogmatism, intolerance, and societal divisions. Every day, we are bombarded with news reports of protests related to conflicts associated with social values. Some of them are extremely violent and result in the loss of human lives. As a dramatic example, in November 2002 in the city of Kaduna, Nigeria, around 250 people were killed in a series of religiously-motivated riots. The apparent trigger for the violence, which became known as the "Miss World riots," was an article published in a Lagos-based newspaper that was perceived as blasphemous by some Muslims. Within days, expressions of displeasure or offense at the article were seized upon by some militant groups, and the protests turned violent. Muslims attacked Christians and Christians retaliated against Muslims. Both groups went on a rampage, killing, burning, and looting. Not lethally violent, yet still concerning, decades ago, following the publication of Thornhill and Palmer’s academic book on “A natural history of rape –biological bases of sexual coercion,” which offered a different view on rape contrary to social constructivism that considers it an expression of male domination without sexual arousal, Joan Roughgarden vehemently responded in the journal Ethology (2004), arguing that “critics of evolutionary and human-sexuality psychology should realize that they're dealing with a political fight more than an academic dispute. We must organize as activists to oppose this junk and get out of our safe comfortable armchairs, for much is at stake. Thornhill and Palmer are guilty of all allegations, and they deserve to hang.”3

Moralization can therefore inspire benevolent forms of collective action like the American civil right movement, but it can also incite dogmatism, intolerance, division, authoritarianism and harmful consequences (i.e., aggressive attitudes, justification of prejudice, vigilantism, and political violence) against people or groups who share different values or practices (Yoder & Decety, 2022).4 All are serious threats to personal autonomy, civil liberties and political rights. In the United States as well as a growing number of countries, liberals and conservatives are often incapable of reaching policy agreements on polarized social issues, from gun control to economic policy to health care and climate change. This partly stems from divides in fundamental values (Marie, Altay & Strickland, 2023). In August 2023, the number of Americans who believe the use of force is justified to restore Trump to the White House increased by roughly 6 million in the last few months to an estimated 18 million people, according to a survey conducted by the University of Chicago Project on Security and Threats.

Moralization frequently occurs in the public domain (e.g., about smoking, sexually transmitted diseases, vaccinations). It can be a positive force by signaling that an issue is morally important, and lead to good outcomes, but it can backfire and lead to psychological reactance, a motivational state of resistance, and bring about the opposite effect of the intended behavioral change (Kraaijeveld & Jamrozik, 2022). For instance, moralization of public health issues can legitimize stigmatization, ostracism and political division with counterproductive outcomes. In one study, female subjects were exposed to a stigmatizing versus non-stigmatizing health message with forceful versus non-forceful wording (Schnepper, Blechert & Stok, 2022). Then, the effects on a virtual food choice task (healthy versus unhealthy), diet intentions and concerns to be stigmatized were measured. The results indicate that in the non-stigmatizing and non-forceful condition, participants made the highest number of healthy food choices. Conversely, in the two stigma conditions, higher body mass index correlated with higher concern to be stigmatized, highlighting the adverse effect a health message can have. Opiates were not moralized in the past century, and morphine was a respectable medical treatment for alcohol addiction (Siegel, 1986. Today, the use of opiates is moralized and criminalized, and yet according to the National Center for Health Statistics over 106,699 drug-involved deaths (mostly opioids) were reported in 2021 in the US.

It is, therefore, important to understand the motivations, psychological mechanisms, and social variable that underlie and predict why and when moralizing can be dangerous. This knowledge is valuable in finding ways to facilitate tolerance between individuals, to encourage openness to alternative points of view, to reduce dogmatism, and to avoid legislative gridlocks. For example, the propensity in the United States to moralize attitudes on a variety of issues such as social justice, illegal immigration, vaccination, health care coverage, income inequality, or gender equality predicts greater social distance as well as prejudice, anger, incivility, and antagonism toward supporters who hold opposing beliefs (Garrett & Bankert, 2020). This polarization, which is largely affective, is not the direct cause of political violence. But it does help create an environment that allows opinion leaders to increase violence against politicians, election officials, women, and many types of minorities. It fosters an anti-establishment sentiment with a distrust of institutions and science. An editorial published in Science, one of the world’s top academic journals, by a group of psychologists and sociologists sounded the alarm about political bigotry in the United States, calling it a poisonous cocktail of alienation, aversion, and moralizing that poses a serious threat to democracy (Finkel et al., 2020).

While morality binds us to others, allowing for more harmonious cooperation and coordination–undoubtedly essential foundations of our civilization, it can also blind us to distrust and demonize those who do not think, behave, or agree with us. At times, morality can motivate and justify intolerance and violence. Some people commit acts of violence because they sincerely believe that it is the morally right thing to do. In the minds of many perpetrators, violence can be a morally necessary and appropriate way to regulate social relationships according to precepts and cultural prototypes. These moral motivations apply equally to violent heroes of the Iliad as they do to contemporary environmental activists who destroy agricultural crops in opposition to genetically modified organisms, death threats against two Australian philosophers who suggested in an academic paper that newborns and fetuses are morally equivalent ''potential persons'' whose family's interests override theirs, rioters of religious and ethnic rights through India and Africa, or parents who use corporal punishment to discipline their children.

Dogmatism, intolerance, and resulting physical, verbal, or symbolic violence motivated by moral conviction are thus serious concerns in today’s world. Moralized identification with one group/coalition leads to polarized attitudes, identity-based ideology (whether it’s gender, sexual orientation/identification, religion, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status), and sectarianism. The more individuals are certain of a belief –regardless of its objective correctness—the more durable it will be, and the more willing they are to express their opinion and shun others who do not accept their views (Tormala & Rucker, 2015), and polarize the political debate. Social media, currently used by 5 billion people, amplifies polarizing and divisive messages, especially for moralized content (Rathje et al., 2021). Such a combination is potentially toxic and undermines our democracies, as well as our capacity to harmoniously live together and find pragmatic solutions to current challenges. It seems rational to strongly defend a view about facts that one evaluates as beyond doubt, like the earth is round or viruses evolved faster than any other living organisms. Distinguishing the epistemology of factual and normative beliefs is important to consider.

A functionalist perspective on morality

Moral thinking pervades our lives, and this is specific to our species. The human predisposition for social preferences5 and cooperation has emerged through natural selection in part due to the benefits it conferred on our ancestors living in large groups. This requires complex systems of social evaluation to distinguish individuals who can be trusted, who are likely to cooperate from those who are not. Our species has the propensity to produce cultural organizations that create social norms (regulation of acceptable and standard ways of behaving and achieving goals) and enforce them through institutions designed to assess the acceptability of individuals' behaviors and assign appropriate punishments to those who violate social norms (Tomasello, 2016).

A large body of literature in anthropology, psychology and economics indicates that our species has evolved interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions that work together to suppress or regulate self-interest and make cooperative societies possible (Haidt, 2011). These adaptations are thought to be the product of gene-culture coevolution (Bowles, 2016; Boyd, 2018; Gintis, 2011; Henrich, 2016). All human societies develop social norms and systems of social regulation, which owe their effectiveness to the ability of individuals to integrate, share, and respect them as much as have them respected by others. This enables stability in living together and promotes large-scale cooperation (Boyd, 2018). Morality regulates interpersonal exchange, facilitates survival, coexistence, and cooperation, minimizes aggression, and more generally provides a balance when individual interests conflict with collective interests (Curry et al., 2009). While it is true that many non-human animals collaborate with their own species, humans are exceptional in their social preferences. They help one another based not only on kinship and reciprocity (direct and indirect), but also on apparently unselfish motives driven by altruism, empathy, and benevolence. Humans seek means for all to benefit through enacting norms to promote and maintain fairness, equity, and justice within the community. Social preferences are associated with happiness and well-being (Iwasaki, 2023). Many studies have reported a correlation, and some have found a causal reciprocal relationship between behaving prosocially and happiness (Aknin & Whillans, 2021; Meier & Stutzer, 2008).

We are motivated by morality because it is advantageous at the individual level –a non-zero-sum game (Delton & Krasnow, 2015)6. These moral concerns are not located in an abstract world characterized by ivory tower speculation. We are inherently and deeply social animals. Nearly all manifestations of morality involve, build upon, influence, and often govern our relationships with others. The ability to think and act in accordance with moral norms is a hallmark of our species. Of course, we are not conscious of the ultimate explanation of behaviors (the why question), those concerned with fitness consequences.

A strong argument in favor of the evolutionary origins of morality comes from developmental research demonstrating that the foundational aspects of social evaluation and precursor of morality are present early in ontogeny, before input from socialization (Decety, Steinbeis & Cowell, 2021; Tomasello, 2014). Preverbal infants possess an innate system of social evaluation that is similar to what evolutionary biologists, anthropologists, and psychologists have posited to be required for the emergence of our species' sociability (Hamlin, 2013). They distinguish between positive and negative social interactions, positively evaluate those who cooperate and negatively evaluate those who do not, expect other people to prefer those who have helped versus hindered them, and consider mental states when evaluating others (Decety, 2019; Cowell & Decety, 2015; Hamlin, 2015; Ting et al., 2020). Before their second year, toddlers direct their own antisocial behaviors appropriately, selectively taking resources from someone who has previously hindered a third party (Hamlin, Wynn, Bloom, & Mahajan, 2011), and showing concern for issues of justice and fairness (Ting et al., 2020).

Children as young as 15 months perceive the difference between equal and unequal distribution of food, and their awareness of equal rations is linked to their willingness to share a toy (Schmidt & Sommerville, 2011). Subsequent studies with infants of the same age demonstrate that they use fairness concerns to guide their social selections (Burns & Sommerville). However, infants also take into consideration the race of individuals, and the consequences of the behavior of these individuals for their own- versus other-race individuals. When the distributor’s race (Caucasian vs. Asian) is pitted against prior fair behavior, infants no longer systematically select the fair distributor, suggesting that infants incorporate information about the individuals’ races when making social selection, and weigh race and fairness as competing dimensions in their social decision.

Ingroup favoritism – the tendency to favor members of one's own group over those of other groups emerges early. For instance, research indicates that 17-month-old infants possess an abstract expectation of ingroup support that already guides their reasoning about how individuals will act toward others (Jim & Baillargeon, 2017). When an individual needed help and another individual from the same minimal group was present, infants expected this second individual to support her ingroup member; no such expectation arose when the two individuals were not members of the same group. Infants around 14 months old begin to show cooperative behaviors, such as spontaneously and indiscriminately helping others (Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). This disposition is then influenced by judgments of likely reciprocity and their concern about how they will be evaluated by others (reputation) (Engelmann & Rapp, 2018). In costly sharing and prosocial tasks, when sharing incurs no cost, 5-year-olds treat kin and friends more favorably than strangers, while 6-year-olds favor kin over friends when sharing resources incurs a cost, showing kin favoritism (Lu & Chang, 2006).

In their second year, infants possess context sensitive-expectations relevant to fairness. They expect an experimenter to give a reward to each of the two individuals when both have worked to complete an assigned chore, but not when one has done all the work while the other was playing (Sloane et al., 2002). Across cultures, young children show a desire to appear fair in resource distribution and are more willing to distribute resources equitably with age, suggesting a universal increased preference for equity over equality throughout development (Huppert et al., 2019). A rudimentary understanding of the normative dimension of human actions can be observed in 18-month-old toddlers (Schmidt, Rackoczy & Tomasello, 2019). Normative behavior develops around 3 to 5 years of age, without explicit teaching. Young children of this age can distinguish prescriptive from descriptive social rules (Nucci, 2001; Smetana, 2013; Sripada & Stich, 2006). Around the same time, children express obligatory judgments based on moral concerns with others’ welfare, rights, and fairness through spontaneous reactions and reasoning about perceived violations, and begin to enforce social norms on others (Killen & Smetana, 2015).

Morality incorporates multiple dimensions, including sensitivity to social norms, values, reputation, and the set of capacities involved in reinforcement learning (including reward and punishment-based decision-making). It involves nonconscious and implicit processes such as an aversion to harming the vulnerable, concern for others, social emotions (e.g., guilt, shame, outrage, gratitude, and pride), as well as more conscious processes such as theory of mind and deliberative reasoning (Decety & Cowell, 2018; Van Bavel et al., 2015). Although moral values are personal in the sense that they are internalized, they are acquired in a social context and are shared with others from our social group (Schwartz, 2014). The mechanisms by which beliefs are conferred and become shared include the propagation of social norms about common goals and the establishment of moral principles or standards of conduct that should be followed.

Social groups play a key role in the establishment of prescriptive social norms. Importantly, decisions and behaviors that uphold moral values are perceived as highly rewarding (Bartels et al., 2015; Yoder & Decety, 2018). Moreover, judgments about moral norms are highly affected by social conformity. In keeping with the large body of work showing how decisions and behaviors are influenced by majority opinions, some studies have demonstrated that moral judgments are subject of conformity pressure. In one study, participants were asked to make decisions about sacrificial dilemmas either alone or in a group of confederates (Kundu & Cummins, 2013). Under social conformity, permissible actions were deemed less permissible and impermissible actions were judged more permissible. Another study found that while subjects do tend to conform to the majority opinion on moral matters, they do so in a selective manner by conforming more when the majority opinion is of a deontological nature than when it is of a consequentialist nature (Bostyn et al., 2017). This asymmetric conformism effect is theorized by the authors to be driven by strategic concerns related to mutualistic partner choice preferences.

Across studies in social psychology and cognitive neuroscience, it is well documented that the opinion of others modulates the reward and value systems. In particular, the magnitude of activity in the ventral striatum reflects the value of reward-predicting stimuli (Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., 2010). Social influence mediates very basic value signals in known reinforcement learning circuitry and explains the swift spread of values throughout a group of individuals. The reward circuit generates signals related to a broad spectrum of social functioning, including making decisions influenced by social factors, learning about other members of our communities, and following social norms (Bhanji & Delgado, 2013).

Morality is generally thought to be based on injunctive and descriptive norms about how people should behave toward each other (Killen & Smetana, 2015). Descriptive norms are simply regularities of behavior, what most people do in a given situation, while injunctive norms are behavioral expectations supported by social or material sanctions (Simpson & Willer, 2015). A substantial body of evidence shows that people conflate what is descriptively normal (common or frequent) with what is prescriptively normal (allowed or required), reflecting the common-is-moral association (Heyes, 2024). When 35,000 participants from 30 European countries were asked to evaluate the morality of questionable behaviors (e.g., cheating on tax declaration or having casual sex), there was a positive correlation between their ratings of the frequency and justifiability of the behavior (Eriksson et al., 2021). Injunctive norms have an effect. For instance, studies conducted among Christians-American have found that participants donated more money to charity (Malhotra, 2010) and watched less porn on Sundays (Edelman, 2009). However, they compensated on both accounts during the rest of the week. Likewise, a study conducted in Morocco found that whenever the Islamic call to prayer was publicly audible, local shopkeepers contributed more money to charity (Duhaime, 2015). However, these effects were short-lived. Donations increased only within a few minutes of each call and then dropped again.

Numerous other studies have yielded similar results. People become more generous in a donation task (Xygalatas et al., 2016) and cooperative in a bargaining game (Xygalatas, 2013) when they found themselves in a place of worship. Importantly, this effect is not due to intrinsic religiosity (the disposition) but an artifact of contextual cues (the situation).

In addition, one's own survival and success depend on trustworthy, competent, and motivated collaborative partners (Noë & Hammerstein, 1994). Thus, within a cultural group, individuals are concerned with how others evaluate them and invest energy to maintain the appearance of being fair and keep a good reputation (Caviola & Faulmüller, 2014). Conformity to the prevailing practices and social norms is vital to advertise group identity. It is plausible that morality is the product of cultural evolution over a potentially shorter period, by selecting cognitive and motivational mechanisms specialized for processing social norms (Heyes, 2024). Her cultural-evolutionary model proposes that norm psychology depends on implicit domain-general processes (perceptual, attentional, learning, motivation) that are genetically inherited as well as explicit domain-specific processes that are culturally inherited. Such capacities and practices have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years since humans first banded together for fitness and survival.

Moreover, some evolutionary anthropologists have argued that moral judgment is routinely strategic (DeScioli et al., 2014). Human societies have a variety of rules, and some benefit some people more than others. This panoply of moral rules with differential effects is part of the enduring social ecology of Homo sapiens, and natural selection has favored cognitive adaptations for advocating rules that enhance the individual’s fitness (Mercier, 2011). Group living has persistently constituted a fundamental aspect of our evolutionary history, and thus selection has favored psychological adaptations to enable and regulate behavior both within and between groups (Forgas et al., 2007).

Overall, morality has evolved as a regulatory system that includes the creation and sensitivity to social norms, notions of justice, fairness, and rights, and a meta-perception of some of our decisions, judgments, and attitudes that can vary in intensity. Overall social and moral norms facilitate a harmonious and cooperative co-existence, especially when individuals have a high degree of conformity.

Social domain theory of morality

Over decades of research in psychology, it has become clear that what people subjectively experience as moral is psychologically different from what they experience as social preferences or conventions. Across cultures and very early in development, people classify behaviors, values, beliefs, and practices into distinct categories (Smetana, 2013; Nucci, 1996; Turiel, 2006). The moral domain includes actions considered inherently wrong because of their detriments on the well-being of others, such as physical and psychological harm, violations of property, or damage to equity. The moral domain thus brings together prescriptive judgments of justice, rights, and welfare considerations relating to how people should treat each other. Moral judgments are impersonal, generalizable, and motivate the possibility of sanction to enforce respect for people and their rights. The conventional domain includes actions that are not inherently wrong but whose wrongfulness depends on the existence of a rule or norm (such as how to dress for a wedding or a funeral), and these rules and judgments of the conventional domain vary according to time and place. They are, therefore, not universal. Judgments that fall into this category are justified by reference to the maintenance of social norms and respect for authority. Finally, the personal domain encompasses preferences and actions whose consequences do not affect other people or society (the private sphere). Though people disagree about what falls into each of these three domains, once a belief, value, or practice has been categorized into one of them, the categorization consistently and powerfully predicts people’s responses to it, especially when it differs from their own (Wright, 2023). Overall, the wrongness of moral transgressions is seen as stemming from their intrinsic features, such as their intrusion on others’ rights and welfare (Smetana, 2013). Morality is seen as normatively binding, and thus, moral rules are hypothesized to be unalterable. However, depending on the culture, moral principles may carry different weight, and the boundaries between domains are fuzzy. Depending on historical epochs, social ecology (population density, mobility, pathogen avoidance, weather), religious beliefs, and institutional rules (e.g., kinship structure and economic markets), each society develops a moral system that emphasizes specific orientations (Bentahila et al., 2021). Furthermore, there are cross-cultural differences in the tightness of social norms that impact the enforcement of moral rules and punishments (Gelfand et al., 2017).

Another theoretical perspective proposes that moral beliefs and attitudes are a matter of degree rather than just a matter of kind. The moral significance that people attach to different issues or problems varies according to historical time, culture, and geography (Skitka et al., 2021). Attitude toward smoking, for example, has evolved from a matter of preference to increasing moralization over the past 60 years. Similarly, there was a time when abortion was unrestricted by law in the United States, and abortion services were openly marketed. Abortion restrictions in the United States were not initially grounded on moral concerns, but were rather rooted in concerns about medical licensure and the desire of increasingly professionalized healthcare providers to stem competition from midwives and homeopaths (Reagan, 2022). Attitudes toward abortion vary widely across cultures (Ryan, 2014). Today, however, abortion has become a highly moralized and politically polarizing issue in the United States, mostly for white evangelical Christians. They consider abortion to be morally wrong, and argue that it should be illegal. However, relatively few Americans actually view the morality of abortion in stark terms. According to a 2022 Pew Research Center report, 7% of all U.S. adults say abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third of them say that abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable most of the time. About an additional one in five do not even consider abortion a moral issue.

In this theoretical context, morality is not an essential characteristic of certain domains of decisions, choices, judgments, or attitudes. Rather, it is a meta-perception that people have of some of their decisions, beliefs, judgments, and attitudes, which can vary in strength. Morality is a matter of degree rather than a matter of kind.

The fact remains that our capacity for morality is universal. It must be understood by distinguishing a moral capacity and moral values: while our moral capacity is universal, the moral rules and values we develop are quite diverse. They vary according to times, places, cultures, history, and our choices. For example, bullfighting is considered a barbaric and immoral practice of animal torture in many countries where it is therefore prohibited, while it is perceived as a cultural heritage in Portugal, Spain, Venezuela, and southern France where it receives public subsidies. In 2020, same-sex relationships were punishable by law in 69 out of 193 countries and carry the death penalty in 11 countries. Currently, gay marriage is legal in 34 countries.

How do we reconcile the universality of our moral capacity and the plurality of our morals? Contrary to what is too often believed in social sciences, a naturalist perspective on morality is not necessarily reductive. It does not eliminate levels of organization. Rather it seeks conceptual unity and relations that cut across levels. Complex phenomena require accounts at multiple levels of organization. Different levels must be mutually compatible, but no one level reduces to another (Barkow, 1991). In fact, this perspective can help us understand our moral capacity's natural basis without limiting its diversity. Here, the usual dichotomy between nature and nurture is misleading and unnecessary. It is no longer defended by most evolutionary/cultural anthropologists. All humans possess an evolved ability to create, learn, and uphold moral rules and social norms and adapt them to new situations. Therefore, moral cognition is itself universal, whereas moral rules differ from group to group and within the same group over time.

Morality corresponds to a set of principles and norms that guide the conduct of individuals within their group. While some moral principles seem to transcend time and cultures, (e.g., fairness or family obligations), moral values are generally not set in stone. Almost all manifestations of morality involve, rely on, influence, and govern our relationships with others.

Virtuous violence

Violence is generally and wrongly considered as the antithesis of sociality. It is usually seen as an expression of our animalistic nature, which is expressed when learned cultural norms break down or when our ability to control and inhibit ourselves is deficient. Violence is also perceived as the essence of evil, the prototype of immorality. It manifests in many different ways such as a reflex behavior (reactive aggression), coercion, threat of physical force, hostility, and terror, and thus needs to be determined by assessing intentionality. Studies in behavioral ecology and anthropology indicate that humans have a high potential for proactive aggression (involving some degree of premeditation) toward their fellow humans, including lethal violence, an attitude we share with other primates, and chimpanzees in particular (Gómez et al., 2016). Furthermore, this potential for violent aggression is much higher in men than in women, likely due to an unusually high benefit/cost ratio for intraspecific aggression in the former (Georgiev et al., 2014). Overall, human aggression is characterized as a combination of low propensities for reactive aggression and coercive behavior and high propensities for proactive aggression (especially coalitionary proactive aggression). These tendencies are associated with the evolution of groupishness, self-domestication, and social norms (Sarkar & Wrangham, 2023).

Most psychological theories of morality hold that at their core, moral judgments always include a prohibition against unprovoked killing, harming, stealing, and lying (Turiel, 2012; Gray et al., 2012). Support for violence can only be construed as a moral violation, an error in moral performance, or a necessary evil to achieve a greater good. Yet, historically, harming others, even family members, has been considered morally laudable, consistent with coalitional psychology. A striking illustration can be found in the Old Testament (or Torah), Exodus 32:28, where Moses commands, “Let each one of you lay down his sword to one side; cross and go through the camp from gate to gate, and let each kill his brother, his relative”. About three thousand people perished that day for committing the sin of worshiping a golden calf. Punishing one's own children for disobedience, sometimes very severely, is seen not only as a necessary evil but as a virtuous action in many parts of the world. This story in Exodus is consistent with the common observation that people respond aggressively, with anger, to those who act in ways that threaten their group’s identity, particularly when they affiliate strongly with their group. Experiments in social psychology reliably show that behaviors that violate moral norms when displayed by ingroup as compared to outgroup members are associated with ingroup‐directed hostility through collective shame, psychological distress, and experience of threat to shared values (Fousiani et al., 2019; Marques et al., 1988). When a threat to one's group identity comes from the inside, that is, from an ingroup member, people react with hostility and respond by treating the ingroup transgressor very negatively (Marques & Yzerbyt, 1988). This happens because a norm violation by ingroup members jeopardizes the reputation of the ingroup and increases ingroup identity threat (Van der Toorn et al., 2015).

Likewise, many people feel morally obligated to physically and violently punish certain transgressions committed by individuals from an outgroup. Two polls of American public opinion found that support for disproportionately killing civilians and enemy combatants, with nuclear or conventional weapons, was deeply divided along partisan political lines (Slovic et al., 2020). Those who approve of these excessively lethal attacks generally adhere to conservative values. They feel socially distant from the enemy and therefore believe that the victims are responsible for their fate. These same people also tend to support national policies that protect gun ownership, limit abortion, and harshly punish immigrants and criminals.

Across cultures and history, violence is used with the intention of maintaining order and can be expressed through war, torture, genocide, homicide, or violent conflict between ethnic groups (Fiske & Rai, 2014). Anthropological, evolutionary, and sociological analyses indicate that many people believe that violence can be just and that victims of violence were the cause of what happened to them–the husband who avenges the murder of his wife; the vigilante who punishes criminals; the soldier who kills his enemy; the public who votes for capital punishment; family members who torture and kill a young girl because of whom she dates, how she dresses or her refusal to submit to forced marriage; and even the suicidal terrorist who detonates a bomb–all evoke violence as morally justified, obligatory and praiseworthy (Atran, 2010; Boyd et al., 2003; Black, 1983). People may commit acts of extreme violence because they sincerely believe it is an imperative, the right thing to do. This is the case of vigilantism, an organized effort by a group of "ordinary citizens" to uphold norms and maintain public order on behalf of their coalition (Asif & Weenink, 2022). In the minds of these actors, such violence is a necessary and legitimate means of regulating social relations in order to restore the integrity of moral imperatives according to principles, precedents, and cultural prototypes specific to their group.

Anthropologists Rai and Fiske (2011) propose that moral judgments are not independent of the socio-relational contexts in which they occur. Our moral intuitions are defined by the relations in which they appear. Intentionally harming others will be perceived as more or less acceptable, even morally laudable, depending on the relational and cultural context. These prejudices range from verbal aggression to large-scale ethnic conflict. A given action is deemed good, just, equitable, honorable, pure, virtuous, or morally correct when it occurs in specific socio-relational contexts. It is also be deemed wrong or unjust when it occurs in other socio-relational contexts. Guided by this theoretical framework, Fiske and Rai (2014) proposed that any action, even violent, can be morally just insofar as it regulates the socio-relational context defined by culture, whether it is within a family, ethnic group, military unit, religion or nation. Actions that violate the relational model that actors use are considered immoral. For relationships to work, people need competing motivations that lead them to regulate and sustain social relationships by controlling their own behavior and sanctioning others. Therefore, the core of our moral psychology consists of grounds for evaluating and orienting our judgments and behaviors, and those of others (including speech, emotions, attitudes, and intentions) with reference to prescriptive models. Behaviors that do not conform to relational prescriptions are considered moral transgressions and arouse emotions such as guilt, shame, disgust, envy, or indignation. These emotions motivate sanctions, including apologies, repairs and rectifications, self-punishment, and modulation or termination of the relationship.

The existence of groups and the social processes associated with them lead to solidarity from the group and disapproval from without under conditions where differences between groups become salient. Also, strong moral beliefs and values are often linked to greater defense when threatened. This can be explained by both social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) and coalition psychology (Boyer, 2020).

A stark example is the religious fundamentalism of which the French became sorely aware of after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris on January 7, 2015, where 17 people who worked in the offices of the satirical magazine and a Jewish supermarket lost their lives, shot by Islamic militants. In a study of more than 52,000 people in 59 countries, Muslims reported a greater number of fundamentalist beliefs than followers of other religions, including Protestants, Catholics, Hindus, and Jews (Wright, 2016). The link between fundamentalism, dogmatism and hostility is well-established. The higher the level of fundamentalism, the greater the hostility towards an outgroup (Henderson-King et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2012; Rothschild et al., 2009). However, it is unclear whether fundamentalism is a direct cause of or exacerbates reactions to social identity threats. Among most of the Muslim publics polled by the Pew Research Center in July 2011, and important variable emerged: Muslims tend to identify with their religion, rather than their nationality. This is particularly true in Pakistan, where 94% think of themselves primarily as Muslim instead of Pakistani. This is also the case in Israel, Jordan and Turkey. What makes religion unique apart from generic discussions of social identity is a belief in the supernatural, the meaning of this belief to the individual and the group, and the internalization and integration of religious identity to the individual. However, all aspects of religion that are associated with group hostility, aggression, and violence have direct secular counterparts and thus are not unique to religion (Wright & Khoo (2019). For instance, a series of studies across political and religious contexts examined the association between religion and popular support for suicide attacks (Ginges et al., 2010). The findings show that the relationship between religion and support for suicide attacks is real, but orthogonal to devotion to religious belief in general. The association between religion and suicide attacks seems to be a function of collective religious activities that facilitate popular support for suicide attacks and parochial altruism more generally.

Secular groups also display dogmatic beliefs and fundamentalist values and react violently to threats to them. In the 80’s, loosely organized groups fought against a host of issues, including logging, drift-net fishing, nuclear energy, whaling, and road construction (Eagan, 1996). Their actions were motivated by environmental necessity, leading to uncompromising attitudes and violent actions. Most of their destructive acts targeted property: the spiking of trees to present hazards to loggers who would cut the trees, the dismantling of an electrical transmission tower, and the sinking of ships involved in whaling and drift net fishing.

In North American public and private universities, an alarming number of students approve of the use of violence and find it acceptable to use physical force to silence someone with whom they disagree. Several incidents have taken place on campus, illustrating how moralized and polarized opinions can lead to verbal abuse or physical bullying. For example, a political science professor at Middlebury College in Vermont was injured in the neck by a group of students who opposed a lecturer she had invited to campus. At Reed College in Oregon, students interrupted lectures and bullied a humanities professor who they perceived to be too “Eurocentric” in her class on ancient Greece.

More recently, in several European countries, demonstrations against genetically modified organisms (GMOs) with the destruction of many experimental plots have been motivated by beliefs and values of safeguarding biodiversity. This anti-GMO attitude is not really grounded in the objective scientific knowledge of biology, as indicated by a study conducted in the United States, France and Germany with representative samples (Fernbach et al., 2019). Those with the most extreme anti-GMO attitudes turned out to be the least scientifically knowledgeable. This overconfidence and certainty in judgments and beliefs, combined with cognitive simplicity (i.e., seeing things black or white) makes it easier for people who are extreme in their political attitudes, regardless of political affiliation, to perceive their beliefs as moral absolutes (actions are intrinsically right or wrong, regardless of context or consequence) that reflect an objective, universal truth (van Prooijen & Krouwel, 2019).

Such strong beliefs about what is right or wrong are usually shared within a group or a community, consolidating them and providing them with a unity of motivation that can induce intolerance and at times, extreme actions, including giving one's life for one's group. This is the case of suicide bombers (Decety, Pape & Workman, 2018), ordinary citizens risking their lives for a cause, like an activist in France going on hunger strike to prevent the cutting of trees needed to widen a road (Box 1 for a dramatic example), or less dramatically, refusing any discussion and public debate with other people, including experts, who have a divergent opinion, as we see more and more often with specific communities of activists on the transgender movement (Habib, 2019; Grossman, 2023). The reason often invoked in that context is that debate is hate speech. Restrictions on free expression are demanded in the name of preventing offense. In 2021, transgender activists threatened to beat, rape, assassinate and bomb Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling on Twitter for comments she made about transgender women using women’s restrooms. In the US, several children's hospitals have become targets of far-right attacks and harassment over gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth.

Box 1: Sacrificing her life to protest the release of a comedy film.

On October 18, 1973, 35-year-old Danielle Cravenne, armed with a handgun, successfully hijacked an Air France flight from Paris to Nice to protest the release of "The Mad Adventures of Rabbi Jacob," one of the first films to showcase the orthodox Jewish community. The passionately pro-Palestinian woman who thought that the film was too pro-Israeli launched this desperate act to cancel its release. On board the Paris-Nice flight, Cravenne threatened to destroy the plane if the film was not banned and requested that the plane be directed to Cairo, Egypt. She died on the plane that same day, shot by a tactical police operator disguised as a maintenance worker.

In 1968, Danielle Bâtisse converted to Judaism to marry Georges Cravenne, a French producer and advertising executive. In 1973, he promoted Gérard Oury Tannenbaum's film Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob. The film was released on October 18, 1973. Danielle vehemently disagreed with the film's release at a time when a conflict in the Middle East between Arabs and Israelis, known as the Yom Kippur war, took place. The film deals with relationships between Arabs and Jews and has a happy ending about tolerance towards other religions and cultures. Danielle thought that the film was indecently pro-Israel. According to her friends, “the Arab-Israeli conflict was the trigger for everything in her. She could no longer live in a certain way and couldn't bear the Palestinian minority being persecuted. She was a bit of an idealist.”

Danielle Cravenne’s moral valuation of the rights of the Palestinian people trumped her Jewish social identity and relationship with her husband. This is a strong illustration of the power of moral conviction.

Hatred has been characterized as the negative evaluation of a target that is linked with a moral judgment, and this emotion is rooted in seeing the hated person as morally deficient or as a violation of moral norms (Royzman et al., 2006; Staub, 2004). People are more inclined to engage in attack-oriented actions when they experience hate as compared to anger, contempt, and dislike (Martinez et al., 2022). One study analyzed the linguistic content of 150 online websites of hate groups in North America, like Stormfront.org, which is one of the world’s oldest hate groups—providing an Internet forum for over 300,000 registered users who are affiliated with neo-Nazi and White supremacist groups (Pretus et al., 2023). The results show that hate groups use more moral language in expressing their beliefs as compared with users who complain on online forums, used as controls.

Counterintuitively, violence is not antithetical to morality. It can be a means to justify a virtuous end like in cultures of honor or when restoring social order. Similarly, self-sacrificial behavior, including giving one’s life for a cause, is generally motivated by strong moral conviction.

Coalitional dynamics and morality

Humans are an ultra-social species. This sociality is not a happy coincidence but a biological adaptation: a survival response to evolutionary pressures (Cacioppo et al., 2010; von Hippel, 2018). The degree of sociability between individuals is directly related to the survival and reproductive strategies that dictate the success of a species. When the benefits of living together outweigh the costs of living alone, animals tend to form groups (Alexander, 1974). A phylogenetic comparative analysis of ~1000 mammalian species on three states of social organization (solitary, pair-living, and group-living) and longevity shows that group-living species generally live longer than solitary species, and that the transition rate from a short-lived state to a long-lived state is higher in group-living than non-group-living species (Zhu et al., 2023). Living in groups allows for better protection against predators, facilitates access to resources (information, food, sexual partners), and in humans promotes communal parental care, cooperation, and social learning. Evolutionary and ecological pressures toward individualism and competition are met by the countervailing pressures placed on us by our role in cooperative and interdependent groups. We were successful on the savannah (and everywhere else) because we evolved to develop the capacity to work incredibly well as a team and cooperate in sharing information. For this reason, teamwork and cooperation are highly valued in potential friends and mates, and our collective orientation benefits us individually by helping us gain coalition partners (von Hippel, 2018). Throughout evolution, humans have relied not only on the support of their relatives, but also that of genetically unrelated individuals. Humans have evolved a range of psychological mechanisms that promote an attraction to and capacity for living in groups. The consequence of this obligatory interdependence is that the building blocks of human psychology –emotion, motivation, cognition– have been shaped by the demands of social interdependence (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Humans evolved in the context of intense intergroup competition, and groups comprised of loyal members more often succeeded than nonloyal ones (Richerson et al., 2010). Mathematical modeling of social evolution combined with empirical evidence from anthropology and behavioral ecology, reveal that the motivation to be invested in their own members’ welfare co-evolved with intergroup competition over resources. An optimal condition for genetically encoded hyper prosociality to propagate is when groups are in conflict. In line with cultural group selection theory (Richerson, Boyd & Henrich, 2010), it has been proposed that during the late Pleistocene, groups with higher numbers of prosocial individuals cooperated more effectively and thus outcompeted others (Marean, 2015). As a non-zero-sum game, our morality is grounded in coalitional psychology with competition-cooperation dynamics. Our cooperative dispositions were superimposed onto human psychology–without eliminating those older social adaptations that favor friends and kin–and this renders us susceptible to an inherent conflict between other-regarding and public-minded concerns, as well as gives us more selfish and nepotistic dispositions that other species are spared with (Richerson & Boyd, 2005).

Selection pressures have thus sculpted human minds to be tribal (i.e., a social group sharing a common interest) and fostered adaptations to regulate within-coalition cooperation and between-coalition conflict in what, under ancestral conditions, was a fitness-promoting mechanism (Clark et al., 2019; Kurzban, Tooby & Cosmides, 2001). Specific abilities and motivations have been selected by evolution to enable individuals to act effectively within groups, and at times compete against other groups. Group loyalty and associated cognitive biases exist in all human societies, and explain how they can distort certain beliefs in favor of one's coalition. This is clearly the case in politics, and can be found among both conservatives and liberals in the USA (Ditto et al., 2019). Intragroup bias is not limited to a preference for members of one's own group but encompasses multiple domains of cognition (Boyer, 2020; Petersen, 2015). For example, people do not retain information about their own group and others in the same way. They are far more attentive to disagreements between members of their own group than with members of other groups.

Group dynamics is reflected at a primary sensory level. Perceiving ingroup members suffering causes greater activation of brain regions associated with empathy compared to perceiving outgroup members suffering (Contreras-Huerta et al., 2013; Decety, Echols & Corell, 2010; Decety, 2021). Interaction with members of other groups also has a host of physiological impacts, including cardiovascular, hormonal and stress-related consequences (Boyer, Firat & van Leeuwen, 2015). Identity fusion, a visceral sense of oneness with a group (or group mind), occurs when personal and group identities collapse into a single identity to generate a collective sense and unique destiny (Swann & Buhrmester, 2015). This motivates costly pro-group behavior. Experiments conducted with undergraduate students indicate that strongly fused individuals endorsed self-sacrifice to save others (Swann et al., 2014). When they recognized that their group members were in danger, strongly fused persons became highly emotional and immediately felt as if they themselves were in danger and it did not matter whether one or several ingroup members were threatened.

Social groups–whether small bands of friends, entire nations, gangs, tribes, or unions–exist only because individuals have reasons to participate in them over the long term (Boyer, 2018). Because this reciprocity heuristic is always activated when it comes to real groups, people spontaneously apply it to all group situations. In behavioral economics games, when participants learn that they will receive nothing from others in return for the gifts they have given them, the bias in favor of the group disappears (Yamagishi & Mifune, 2009). When people behave in a way that seems to favor their group members, it's because they are implicitly using a social exchange heuristic, a set of assumptions about the task before them (evaluating different individuals or allocating resources to them) as a form of reciprocal cooperation (Boyer, 2018).7

Coalitions can be characterized as sets of individuals interpreted by their members and others as sharing a common social identity, including propensities to act as a unit, defend common interests, and have shared mental states. People are motivated to help the status of their coalition rise, and will feel increased entitlement to better treatment as it does (Petersen, Osmundsen & Tooby, 2022). They will be motivated to fight any threat to the status of their coalition but will feel lower entitlement if its status falls. This provides a functional account of the intuition that group attitudes provide intangible feelings of self-esteem. An inflated belief in self-superiority is prone to encountering threats and causing violence (Baumeister et al., 1996). This coalitional psychology expresses itself in group psychology, politics, and morality (Tooby & Cosmides, 2010). Thus, it should come as a surprise that the surface contents of moral values function as signals of coalition coordination within groups rather than doctrines selected for their intrinsic appeal (DeScioli & Kurzban, 2018). Moral content is often selected to communicate the emergence of a new coalition or to morally legitimize attacks on rivals based on pretexts arising from the superficial properties of those rivals' moralities. Indeed, people support moral projects not because they have intrinsic appeal, but because of their downstream effects on rivals–for example, by lowering their status or weakening their social power.

From that perspective, morality is not a domain of content–moral values are heterogeneous and contradictory–and group affiliations and coalitions shape the perception and evaluation of the events that concern them and motivate moral judgments accordingly. In line with this theory, a large body of empirical literature shows that individuals are more likely to cooperate and reciprocate with their group partners than strangers (Böhm, et al., 2020). At the proximal level, cooperation is highly rewarding and is associated with increased neural activity in brain areas involved in reward processing, including the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Rilling et al., 2012). Activation of this neural network reinforces reciprocal altruism by motivating participants to resist the temptation to selfishly accept, but not reciprocate, favors. Similar results were found in an fMRI study when participants played a game in cooperation with another person in comparison to playing in competition against someone else (Decety et al., 2004).

Religion is a source of social identity in many parts of the world. Religion provides particularly powerful narratives and conveys a sense of security, stability, and shared values that unify the social fabric. It delivers powerful social signals for cooperation or conflict by making group boundaries explicit and salient. Religious identity marker signals influence perception in an implicit and rapid way. For example, a study conducted in China included participants of Han ethnicity, who are similar in terms of facial features (Huang & Han, 2014). Some of these participants were Christians, and some were atheists. Visual evoked potentials were recorded by electroencephalography (EEG) while the participants perceived faces of this ethnicity either with a neutral expression or with an expression of pain. These faces were marked (with a symbol attached to their collars) as Christians or Atheists. Participants explicitly reported greater discomfort and less empathy for the faces of people who hold different religious beliefs. Religious/non-religious identification significantly modulated the amplitude of evoked potentials (ERPs) as early as 200 ms after the onset of the appearance of the face expressing pain compared to neutral expressions. The amplitude of this signal was significantly stronger when participants perceived the faces of people with whom they shared the same religious affiliation.

A single-word label indicating a person's religious affiliation (Hindu, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Scientologist, or Atheist), without any prior interpersonal interaction or additional information, is sufficient to modulate neural activity in the observer and its direction (positive or negative), and can be predicted from their religious affiliation (Vaughn et al., 2018). In this fMRI study, the neural response in the network involved in emotional empathy was significantly greater when participants perceived a painful event occurring on a hand labeled with their own religion rather than a hand labeled with a different religion. Furthermore, the magnitude of this bias is proportional to the participants’ level of dispositional empathy. The more the participants have an empathetic personality, the more they will exhibit a negative bias towards people in the outgroup.

When making moral decisions after considering a hypothetical crime, people are less willing to report a member of their group than an outsider, despite knowing that the person is guilty (Lee & Holyoak, 2020). Even when the situation is unambiguous and the guilt of their sibling or ally is clear, participants still often refuse to report him to the police. Experiments examining moral obligations showed that people who are impartially prosocial are viewed as less moral and less trustworthy precisely because they are seen as not fulfilling special obligations to their family or group (McManus et al., 2020).

The great religious traditions emphasize the responsibility of believers towards their fellow human beings, by encouraging benevolence and preaching caring for others. It is often said that religious beliefs arouse compassion toward the disadvantaged, which logically can be extended to the attitude toward migrants. However, religion's propensity to elicit compassion is not immune to the phenomenon of social identity and group dynamics. In general, people are more empathetic and prosocial towards members of the group with which they identify, whether it is ethnic, sporting (Fourie et al., 2017) religious, or political (Saroglou et al., 2004). In this latter case, empathy towards members of one's group strongly promotes polarization and intolerance towards people who have other affiliations (Simas et al., 2020). Specifically, religious beliefs are a powerful motivator for compassion, pious people typically direct their kindness toward loved ones and co-religionists (Norenzayan 2014).

Using two priming experiments conducted among American Catholics, Turkish Muslims, and Israeli Jews, Bloom and her colleagues (2015) were able to distinguish the role of religious social identity and religious belief in attitudes toward immigrants. The authors found that religious social identity plays an important role in the integration of immigrants. In the study sample, religious social identity increases opposition to immigrants who do not resemble group members in terms of religion or ethnicity, while religious belief engenders welcoming attitudes toward immigrants from the same religion and ethnicity, especially among less conservative devotees.

The essential function of morality is to regulate social life. It is adapted to the type of group it regulates and is sensitive to relational violations. Thus, it is not paradoxical that any action– even a violent one–can be perceived morally just insofar as it regulates the social-relational context defined by culture (Fiske & Rai, 2014). Furthermore, and consistent with coalitional psychology theory and the social heuristic exchange theory,8 a large body of research demonstrates people’s tendency to derogate deviant ingroup members as a means to protect the group from the threat that they pose to their social identity, coining it the black sheep effect. People display a stronger preference for (specifically) exclusionary punishments against deviant ingroup members through the experience of increased ingroup threat (Fousiani et al., 2019). Third-party experimental economics punishment games demonstrate that non-cooperative in-group members are more harshly judged and severely punished than out-group members, demonstrating the black sheep effect (Shinada et al., 2004). The black-sheep effect is most likely to occur when group-based motivational concerns are activated–for example, when one strongly identifies with the group, perceives a threat to its reputation, or believes that its members are seen as similar to each other and when a group-specific norm has been violated (Jordan et al., 2014). Immoral behaviors by ingroup rather than outgroup members jeopardize the group’s reputation and therefore activate utilitarian (i.e., exclusion-oriented) motives for punishment. Conversely, in-group members who prove their loyalty when a threat is present receive the most positive evaluations (Branscombe et al., 1993).

Political orientation modulates whether people feel inspired and uplifted after watching a video of large-scale protests demanding racial equity in policing. Participants’ political orientation influenced whether they experienced moral elevation while watching a video of large-scale protests for racial equity or a counter-protest video (Holbrook et al., 2023). Conservatives experienced elevation in response to the Back the Blue (BtB) video, (protesters from a counter-movement-BLM, who support the police), while liberals experienced elevation in response to the Black Lives Matter video. Furthermore, the state of elevation experienced by participants in response to the videos was associated with costly behaviors, such as expression in their preferences regarding funding for the police. Elevation evoked by the BLM video was related to a preference for defunding the police, while elevation evoked by the BtB video was related to a preference for increasing police funding. These findings indicate that people’s political attitudes and coalitional affiliation influence their emotional responses and preferences regarding allocating funds to policing and social services. This shows that the same actions or policies can be experienced as moral, and as emotionally moving, in opposite directions depending on our group biases.

Morality is in the eye of the beholder. Prosocial emotions may drive feelings toward enemies we intuitively perceive as driven by hate. Understanding their moral sentiments and motivations may be helpful when negotiating with–or even strategizing against–members of opposing groups.

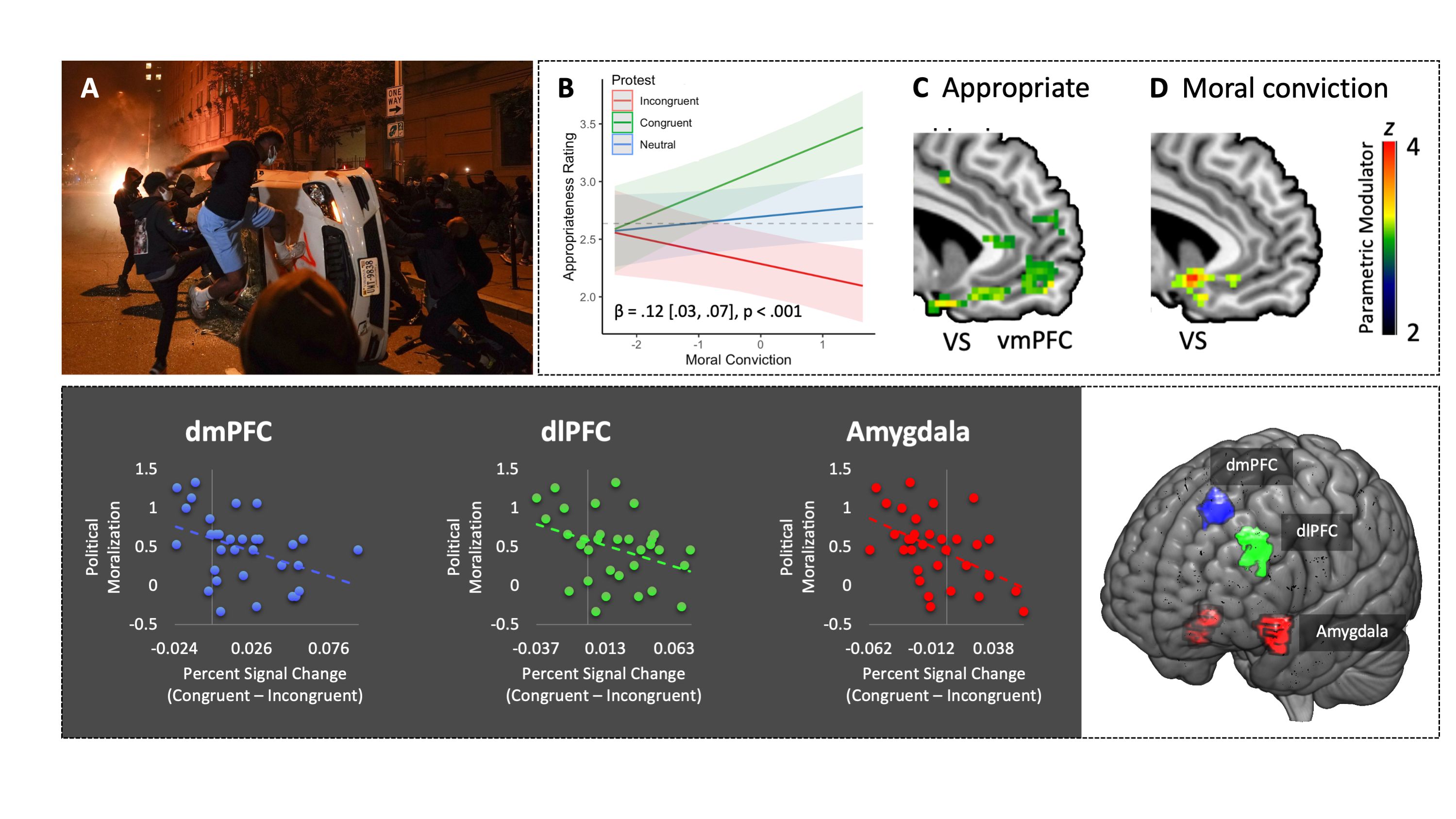

In one study, college students were first surveyed about their political affiliation and moral convictions about various sociopolitical issues (e.g., Black Lives Matter, abortion rights, foreign aid). Then, while in the scanner they were requested to rate the appropriateness of photos depicting violent protests in the United States that were ostensibly in line or not with their moral beliefs (Workman, Yoder & Decety, 2020). The results indicate that the appropriate violence-judgments were associated with a parametric increase in hemodynamic signal within the vmPFC and the ventral striatum (Figure 2). Furthermore, the more the violence is perceived as legitimate, the less the amygdala that encodes emotionally salient information and the prefrontal regions engaged in deliberative reasoning react to these stimuli. The neural circuitry that mediates reaction to congruent (“my-side”) and incongruent (“other-side”) engages circuits involved in the calculation of value and cost-benefit analysis that underpins decision-making.

The activity of striatal neurons reflects reward anticipation, and those in vmPFC encode subjective and motivational values. This makes it possible to establish a link between the cognitive and affective representations necessary to guide social decision-making. Increased hemodynamic activity is detected in the ventral striatum and vmPFC when participants assess, perceive, or even imagine performing positive moral actions versus negative moral actions (Decety & Porges, 2011; Yoder & Decety, 2014ab). This circuit also exhibits signals related to the decision to punish a person who has acted immorally, as well as the observation of a punishment inflicted on someone who has acted unfairly in economic games or who violates social norms (Crockett et al., 2013; De Quervain et al., 2004; Stallen et al., 2018). Activation of the ventral striatum and increased functional connectivity of that region with the orbitofrontal cortex is detected in participants enjoying watching mixed martial arts (MMA), an extremely physically violent sport (Porges & Decety, 2013). MMA fighters are real people; the injuries they suffer in the cage and during practice are often severe. Yet, observers derive pleasure and satisfaction from watching their pain. Notably, the striatum receives converging inputs from the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and amygdala, as well as dopamine signals that guide reinforcement learning, the learned associations between a particular state, and the set of actions with the highest expected values (Krauzlis, Bollimunta, Arcizet & Wang, 2014). This will guide the person’s behavior. It supports the view that attention arises as a byproduct of circuits centered on the basal ganglia involved in value-based decision-making.

In another study, a Thomas sample of Pakistani Muslims supporting the cause of Kashmir was selected on their beliefs and support for the jihadist group fighting for the integration of this region in Pakistan, then invited to participate in an fMRI study during which they were asked to communicate their willingness to fight and die for a series of values related to Islam (e.g., Sharia should be applied in all Muslim countries) and current international politics on a Likert scale of 7-points (Hamid et al., 2019). As in the study by Workman and colleagues (2020), decisions to support the fight for Islamist values are associated with a parametric increase in activity within the vmPFC and a decreased activity within the dlPFC, as well as weaker functional connectivity between the vmPFC and the dlPFC. These results suggest that beliefs to fight and die for Islamist values engage brain regions associated with subjective value coding (vmPFC) rather than material cost integration (dlPFC) during decision-making, supporting the idea that decisions about costly sacrifices motivated by moral values are not to be mediated by a cost-benefit calculation.

Together, the results of these functional neuroimaging studies indicate that strong moral beliefs about sociopolitical or economic issues increase their subjective value, outweighing the natural aversion to interpersonal wrongs. The more moral convictions are associated with non-negotiable, inviolable, and non-utilitarian values, values that resist trade-offs with economic values (Baron & Spranca, 1997), also called sacred values in political science (Tetlock, 2003), the more they correlate with activity in vmPFC in subjects passively exposed to statements that relate to beliefs and attitudes that they have moralized (Pincus et al., 2014). A study combined, in the same participants, measures on a multidimensional political science data reduction scale to investigate the perception and evaluation of political candidates and fMRI when these participants were asked to read and evaluate 80 political statements (Zamboni et al., 2009). The radical (political) dimension of participants' responses is associated with a parametric increase in activity within the ventral striatum and vmPFC. These regions modulate the online expression of pro-violence attitudes, which is consistent with previous work linking this brain circuit to moral beliefs and political radicalism.

When socioeconomic and political issues are highly moralized, individuals to whom they are presented exhibit a pattern of cortical information processing that is prioritized over weakly moralized issues at several stages including early automatic attention. This is reflected by the components of ERPs, especially medial frontal negativity and early posterior negativity (Yoder & Decety, 2022). Furthermore, these quick responses predict a reduction in social conformity (i.e., being concerned with what other people may think). Changes in alpha and beta spectral power indicate increased attention and engagement with moralized content. Together, these electroencephalographic results indicate that strong moral conviction alter the susceptibility to social influence by altering cognitive and emotional processing to prioritize information that relates to previously moralized beliefs. They align with research on attitude strength showing that strong attitudes are resistant to change and are easily accessible (Young & Fazio, 2013).

Coalitional affiliation shapes appraisals of events concerning these groups and motivates emotional responses, rewards and value processing and resulting moral judgment accordingly, especially in intergroup conflicts.

The functional architecture of moral conviction

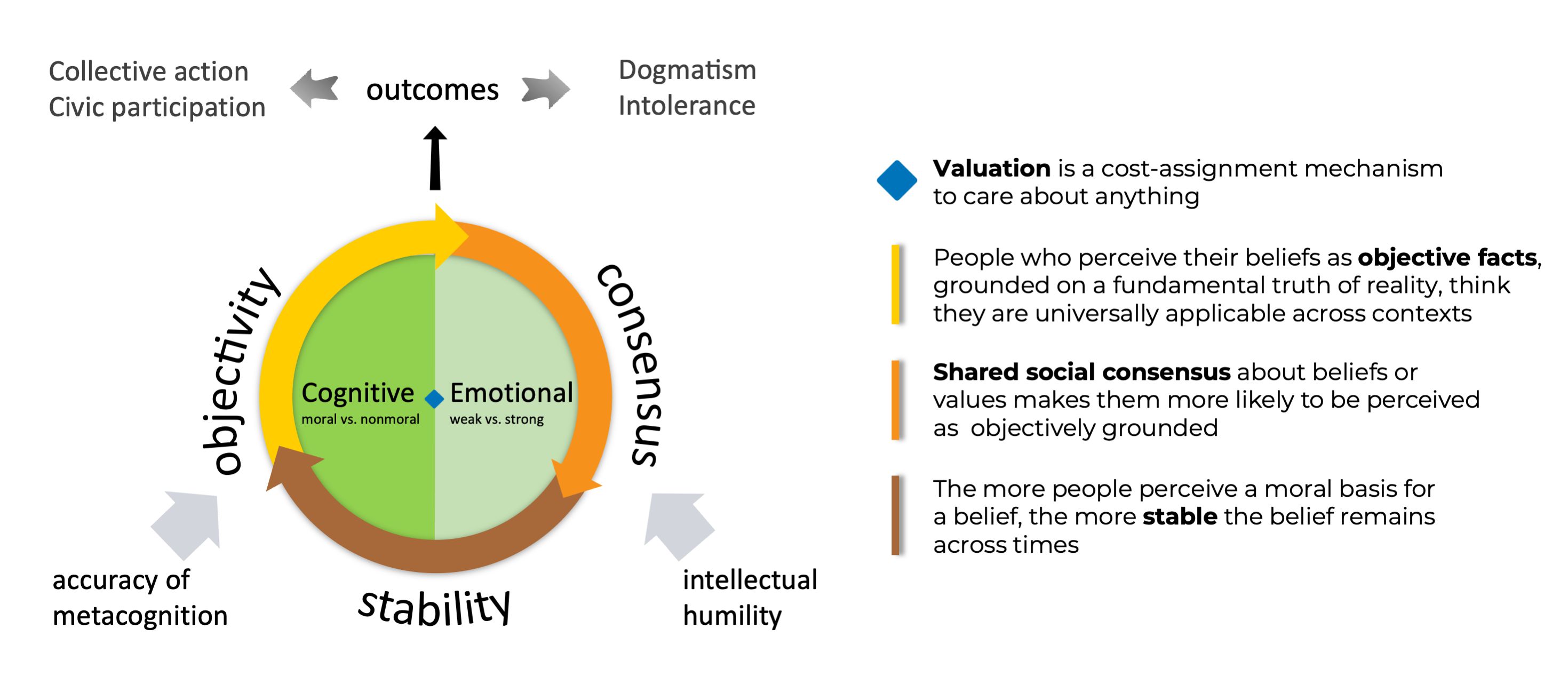

Beliefs and attitudes that are held with strong moral convictions are psychologically distinct from other beliefs. Moral conviction refers to a strong and absolute belief that something is right or wrong, moral or immoral (Bauman & Skitka, 2009). In addition, when a moral belief is perceived as grounded in objective facts, independent from contexts and cultures, it implies that there is only one right answer as to whether something is morally right or wrong, good or bad. Such absolute moral realism, combined with a greater perception of consensus within one’s community or alliance, is associated with feelings of superiority, an inflexible mindset, and intolerance (Wright & Pözler, 2021). Framing an action as moral leads to more extreme and faster judgments (Van Bavel et al., 2012).

Moral conviction can be defined as a set of implicit and explicit representations that incorporates two distinct dimensions: cognitive (moral vs. nonmoral) and emotional (strong vs. weak intensity). A series of experiments conducted by Wright and colleagues (2008) indicate that the cognitive dimension is sufficient to predict most of the negative interpersonal responses to divergent moral attitudes, including greater intolerance, less sharing, and greater distancing from people with divergent attitudes. Emotional intensity, on the other hand, plays a motivational force when combined with moral beliefs, exacerbating their influence (Dancy, 1993; Días, 2023).

Strong moral convictions manifest in the qualities of durability and impact, which are indicators of attitude strength (Krosnick & Petty, 2014). The first aspect of durability is the persistence or stability of the belief, reflecting the degree to which it remains unchanged over time. The second aspect of durability is resistance, which refers to the ability to withstand and react9. Similarly, the attitudinal impact influences information processing and judgments in the sense that certain kinds of information come to mind quickly and render certain decisions. Thus, strong moral convictions are more likely to bias information processing activity and judgments that are weak (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981). Finally, moral convictions can guide behavior, and strong ones are more likely to do so than weak ones.